Chris Powell: Corrupt is corrupt, no matter how many games UConn wins

Logo of the University of Connecticut’s athletic teams.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Secret payments are contradictions of open, accountable and democratic government. They are the essence of government corruption.

Yet last year the Connecticut General Assembly and Gov. Ned Lamont authorized such secrecy. Why? Because it was sought by the University of Connecticut, which is often considered the fourth branch of state government and entitled to whatever it wants.

UConn's rationale for secret payments was ridiculous.

At issue are the de-facto salaries that UConn, like many other schools, has begun paying its varsity student-athletes amid the professionalization of college sports. That professionalization may be fair but it is destroying respect for the college game. The secrecy claimed by UConn will corrupt it.

At UConn's request the legislature and governor enacted an exemption to Connecticut's freedom-of-information law for the payments made by the university to varsity student-athletes as part of sports revenue sharing and for use of their “name, image, and likeness" in advertising. The university says it will disclose the total of these payments and the number of student-athletes receiving them but not individual payments.

“This exemption," UConn Athletic Director David Benedict told the legislature, “will allow student-athletes to maintain their privacy, increase compensation opportunities, and avoid the competitive disadvantages that would occur if Connecticut universities were required to share contract details."

Privacy? How can there be privacy for student-athletes who play before huge crowds, often on television, become the subjects of news reports about their performance, and are followed and admired by millions?

How can there be privacy for student-athletes who hope to parlay their publicity into even more lucrative opportunities in commercial endorsements and the big leagues?

Actual privacy would kill college sports and student-athlete careers.

As for “competitive disadvantages" to UConn if its payments to student-athletes are disclosed, the same argument could be made in respect to all other government employees in Connecticut, whose salaries, thankfully, have not yet been concealed in the name of “privacy." Everyone in government might like his/her salary to be secret. The government itself might like it too, since concealing salaries and other payments would prevent ordinary accountability.

For example, UConn might not want the public to know how its payments to men and women student-athletes compare, nor how payments among members of the same team compare, lest the public sense bad judgment, unfairness, or nepotism and demand answers.

UConn doesn't want to conceal its payments to student-athletes for their sake but for its own.

The university's new exemption from FOI law will facilitate unfairness, unaccountability, and corruption and be a disastrous precedent. The legislature and the governor should repeal it. Corrupt will be corrupt no matter how many games UConn teams win.

THE UNREAL McCOY: Having given up on politics across the state line, former New York Lt. Gov. Betsy McCaughey -- pronounced “McCoy" -- has declared her candidacy for the Republican nomination for governor of Connecticut, where she grew up and to which she has returned, insofar as Greenwich is technically still part of the state.

McCaughey's political life has been erratic. Her governor in New York, George Pataki, a Republican, dumped her, whereupon she became a Democrat and challenged him, only to lose the Democratic primary and then run on the Liberal Party line with even less success. She has supported President Trump and lately has hosted a program on the conservative cable television network Newsmax.

There is speculation that with Trump's endorsement McCaughey could win the Republican primary for governor, whereupon Trump's enthusiasm for her would doom her in the election, but might win her a job in Washington.

In any case McCaughey's opening gambit is tedious. She pledges to repeal Connecticut's income tax, which raises about half the state government's revenue. Voters have dismissed such pledges before, since they are easy to make and impossible to fulfill without massive cuts in state and municipal spending.

Specifying such cuts is where McCaughey should start if she wants to be taken seriously, and even then it will be hard.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

Watchful in winter

“Blue Dogs” (encaustic painting), by Nancy Whitcomb, a member of New England Wax.

Gerald FitzGerald: My love of literature survived brutal teachers

I took beginning French five years straight and never did pass. English was a subject I actually enjoyed, but I remember three English teachers mostly for their brutality.

The first was John P. Gibney, a handsome young fellow who taught my class freshman year at the all-boys Catholic high school, Bishop Loughlin, in Brooklyn.

At Loughlin, teachers changed classrooms each period, not students. Very early on Mr. Gibney came into noisy Room 205 proclaiming: “When I enter this room, silence reigns supreme.”

A few days later, Jimmy Clarke and I were yakking between periods and we didn’t notice Mr. Gibney enter the room. He walked over to his desk on the riser and loudly let fall his books. We looked up, still standing by our seats near the front. Mr. Gibney looked at me, then at Clarke. He extended an arm toward Clarke and moved his index figure in a curling motion. Jimmy’s face dropped its smile, forming a pretty good silent version of “Sorry, sir” as he complied with the signal beckoning him closer. I slipped into my seat and hoped for the best.

It happened so quickly I cannot tell you if Mr. Gibney threw a right or a left. He connected with Jimmy’s jaw, dropping him flat out on the floor. My stomach and legs fell away in fear. Jimmy had not known what was coming whereas I now considered myself fully informed.

Jimmy slowly gained his feet and moved to behind his desk, near mine. I was owned utterly by fear as if awaiting the firing squad. But Mr. Gibney simply started the lesson. Perhaps he thought that he had gone too far, or perhaps he determined that a second assault would not be justified to prove his point. Or maybe that day I was just the luckiest kid in Brooklyn.

There was a big fellow in our class named James E. Freeman. Everyone called him by his last name only. He was very tall and muscular and had a large face and a shock of black hair. He looked just like Li’l Abner from the newspaper comic pages.

Freeman worked hard to make a favorable impression on Mr. Gibney. Seconds before class, Freeman would stack library books on his desk, such as War and Peace, works by James Joyce, poetry and plays. It was as if Freeman thought that the books would trigger Mr. Gibney’s interest, resulting in a literary conversation whereby Freeman might shine and impress. I recall that the teacher once picked up a volume but laid it right back down without stopping. I could not see if he did it with a smirk.

But, once, in the basement hall outside the cafeteria I heard the most gratuitously harsh words spoken by teacher to student. Mr. Gibney was extolling the Irish love of theater when Freeman interjected with his desire to visit Ireland one day and perhaps gain a job working at the legendary Abbey Theater, in Dublin. Mr. Gibney looked directly at Freeman, saying slowly: “Freeman, they wouldn’t let you clean the urinals at the Abbey Theater.”

None of us said another syllable. I watched the hope drain from Freeman’s face. I had neither the brains nor the heart to embrace Freeman or to take a swing at Gibney.

J.E. Freeman apparently grew up in Queens without his father and joined the Marines after high school. He served until he was 22, when he revealed his sexuality and was discharged. He claimed that he was present for the Stonewall Riots, in Greenwich Village, in 1969 and I believed him. He became a professional actor, with roles in such movies as David Lynch’s Wild at Heart, the Coen Brothers’ Miller’s Crossing, Alien Resurrection, with Sigourney Weaver, and the film Patriot Games, based on Tom Clancy’s novel with the same name. He was also kind and caring toward my eldest daughter, Megan, when she tried to break into Hollywood. He died at 68 after having been HIV-positive for 30 years and self-publishing some admirable books of his poetry.

Then there was my other English teacher at Loughlin, Brother Basilian. He was tall and fairly lean, had thinning white hair, and he was clergy -- kind of a male nun with a vertically split starched bib beneath his chin above his long black cassock, the costume of a La Salle Christian Brother.

Brother Basilian’s idea of teaching sophomore Shakespeare was to sit at his desk reading aloud all parts to Julius Caesar. I am happy to note that as a man I have avidly read, no thanks to Basilian, every word known to be written by Shakespeare, as well as many only thought to be written by The Bard.

But at the moment in question, I was utterly bored. My desk was second-to-last in the second row, as I recall. One desk ahead of me, and to my left, sat my classmate Christopher Kenney, surreptitiously reading a Superman comic held on his lap just below Brutus and the gang. In the softest whisper I could make I began to speak:

“Christopher Kenney, this is your conscience speaking.…”

Then, stretching the syllables of his name:

“Chrissss…to..pherrrr Kennn…ney, this is your conscience speaking…” Even from behind I could see Chris’s smile push up into his cheeks.

Suddenly came an unwelcome query:

“WHO IS THAAAAT?” came a wildly abrasive voice from the lips and beet-red cheeks of Bro. Basilian, He slowly rose, his eyes flaming.

Now, he was at the head of my row, swaying side-to-side, striding obsessively toward me down along the aisle.

“IS THAT YOUuuu, FitzGerald?”

He was upon me. He slapped me where I sat, striking my left cheek with his open right hand, twisting my head and neck violently to my right, and then smashed his left hard against my right cheek to send it back. Then his right again to my left cheek, and then his left again to my right cheek. He moved to the rhythm of a butcher. He swung his right open-hand hard and fast toward my left cheek again. I moved my head backward, causing him to miss me completely; his momentum carried him face down across my desk.

Briefly, I caught sight of the frozen, open-mouthed faces of my classmates gaping at Basilian lying across my desk like a roast on a platter. I reached for the hem of his black cassock and pulled it up over his covered black trousers. Then, with a small smile, I whacked his rump in a spanking gesture. The crowd exploded! The cheers and laughter must’ve been heard throughout the entire floor of the building, if not beyond. It was, at that moment, the pinnacle of my life.

Sputtering, the brother clumsily got to his feet, picked me up with both hands and threw me several desks up the aisle. Then did the same again. I finally grabbed the handle on the classroom door and heard him tell me to report to the principal.

Eventually, Loughlin bade me farewell -– unrelated to this incident — and I entered senior year in public school.

The last of my high-school English studies was taught by a woman whose name I recall as Rose Ventresca. Hers was an Advanced Placement class and, of course, I was the new kid in a room half-filled with girls, for the first time since my eighth grade. One early class reintroduced my old pal Shakespeare. Today I take great pleasure reading his sonnets regularly with the authorial tutelage of the late Helen Vendler via her fabulous study, The Art of Shakespeare’s Sonnets.

Our homework for the day of Ms. Ventresca’s class was to briefly explicate each of two sonnets on alternate sides of a loose-leaf page. I have no memory of either sonnet.

The next day I was the first called upon to discuss The Bard’s effort. What I had written to try to explain the first sonnet was right on the money. Ms. Ventresca was thrilled. Her joy at my explication bubbled through the room. I felt enormously proud.

“Read your next explication, please,” Ms. Ventresca commanded. Eagerly, almost boldly, I leapt to fill the air with golden commentary. My eyes never left the page until I was finished reading aloud. I looked up with a broad smile and saw that Ms. Ventresca had shrunk into something vile and withered. There was only foul, frightening silence, soon broken by the brittle, sharp slicing of her teeth and tongue.

“What have you done, you cheating, monstrous fraud? From where did you steal that first, brilliant essay? You cheat! You never wrote that first explication. It’s not possible you could be so right then only to be so wrong! You copied the first one you read from some book. No one could write that and then write such a worthless take on the second sonnet.”

“I am not a cheat, I did not cheat or copy anything,” was all I could stammer back to her wholly false accusation. I have no other memory of any aspect of her class.

Poetry has helped pump my blood since my days cutting classes at Loughlin to spend hours alone wandering New York City memorizing pages of The Pocket Book of Modern Verse, listening to records in booths at the East 53rd Street public library or reading behind the stone lions at the monumental New York Public Library’s headquarters, at Fifth Avenue and 42nd Street, or riding the Staten Island ferry or sneaking into the subway or hiding within The Cloisters or relaxing in my special room at the Metropolitan Museum. If it was free I spent time there with poetry. My best friend, an usher, provided a free pass to Radio City Music Hall, where I sometimes watched three consecutive shows of pretty legs and movies – but always with a book close by.

I still have my books, including a 60-cent paperback of Robert Frost’s poems given to me as my 17th birthday present by my mom shortly after the murder of President Kennedy, for whom Frost was his favorite poet.

I rarely think of my English teachers. They had very little to do with my love of literature.

Gerald FitzGerald, a Massachusetts-based writer, is a former newspaper reporter and managing editor, assistant district attorney and trial lawyer.

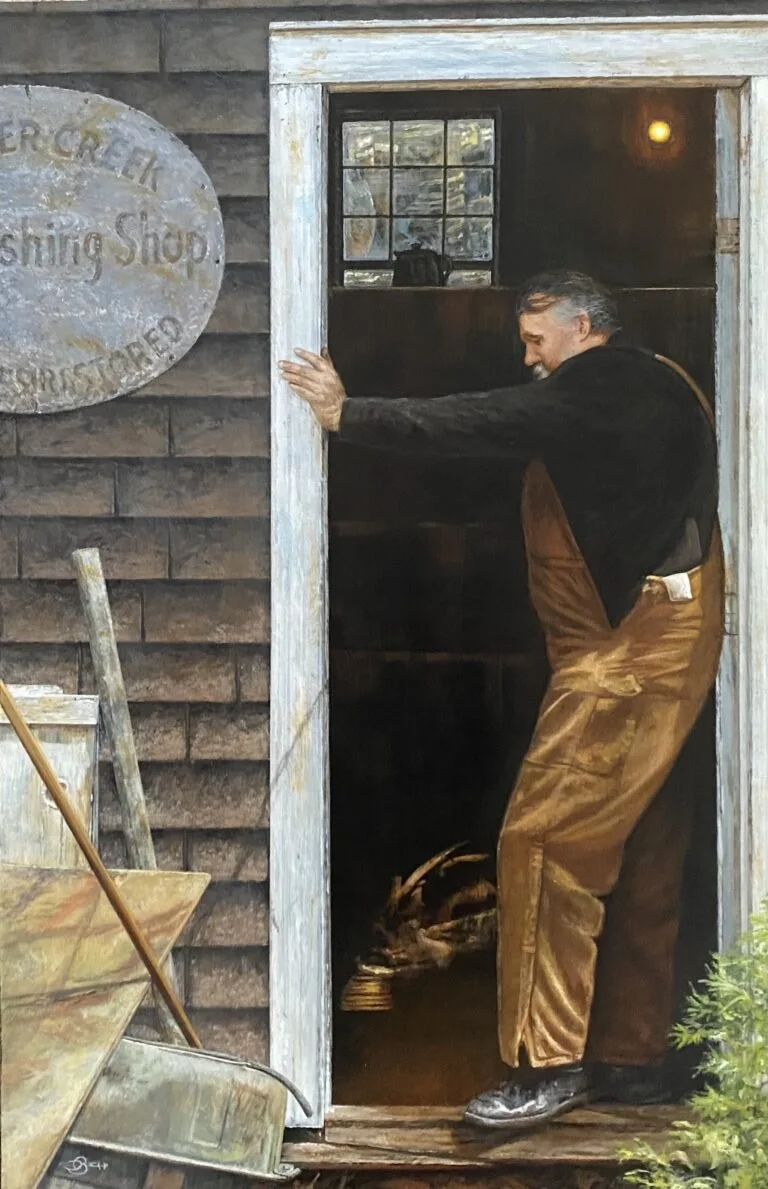

Enough for now

“A Good Day’s Work” (acrylic on panel), by

Del-Bourree Bach, at Copley Society of Art, Boston.

Jean Lesieur, 1949-2026

RIP, Jean Lesieur, famed and brave international journalist, novelist and friend of New England Diary, who has died of cancer in Paris at 76. My wife and I had known him and his family from early 1983 and and have met few if any people who were as impressive in character, intellect, curiosity, work ethic and, I especially note now, loyalty to his friends. And then there was his very funny dark humor.

— Robert Whitcomb

Friendly once you get to know him

“Wilder Mann” (inkjet photographic print), by Jason Gardner, in the group show “Performative Stories,’’ at the Flinn Gallery, Greenwich, Conn., through March 3.

—Image courtesy of Flinn Gallery

The gallery says:

The show features the work of Dan Hurlin, Janie Geiser, Maiko Kikuchi and Jason Gardner. These four artists “employ colorful figures and motion to express varied narratives.’’

“As creators, they ask that you as an audience member apply your imagination to complete their presentations. The works in this exhibition represent narratives that are not only told through words or images but enacted through physical movement and sensory transformation ... often blurring the lines between sculpture, installation, and performance art."

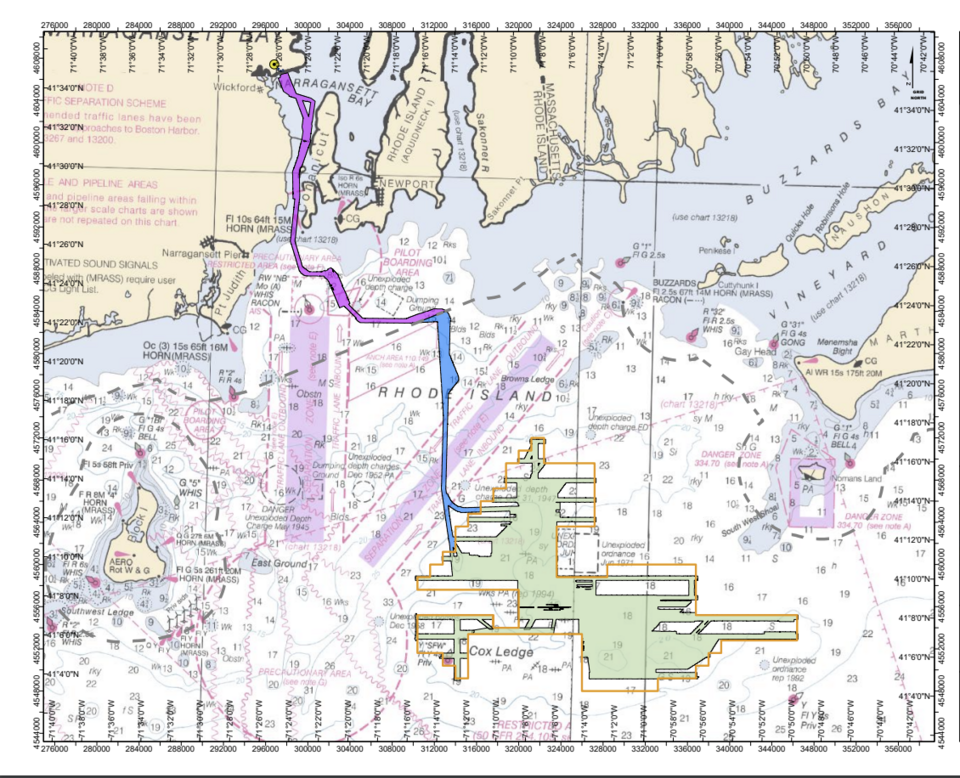

Orsted resumes contruction on windpower project off Rhode Island blocked by Trump

Edited from a New England Council report

BOSTON

Following a U.S. District Court decision overturning a federal stop-work order, construction has resumed on the Revolution Wind offshore wind project. The project — about 15 miles southwest of Point Judith, R.I. — is now more than 80 percent complete. It’s a joint venture of Ørsted A/S and Eversource Energy.

Resuming operations brings about 200 union workers, out of the 2,000 employed throughout the project, back to the construction site. The offshore wind farm had faced a stop-work order issued on Dec. 22 by the U.S. Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Ocean Energy Management.

{Editor’s Note: Donald Trump, tightly allied with the fossil-fuel sector, has sought to kill all coastal- and offshore-wind projects.}

“Safety remains the top priority as construction resumed,” said Meaghan Wims, spokesperson for Orsted A/S. Michael F. Sabitoni, general secretary-treasurer of the Laborers’ International Union of North America and president of the Rhode Island Building & Construction Trades Council, noted the significance of workers returning to the job site after the temporary stoppage.

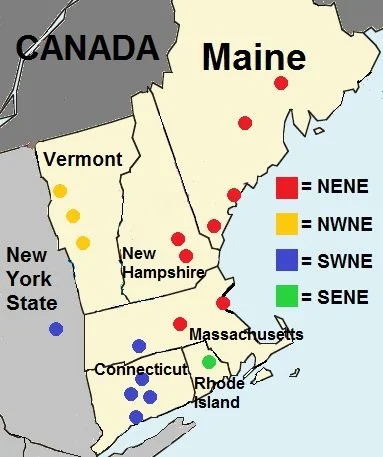

Fading accents

Different New England accents:

Northeastern (NENE), Northwestern (NWNE), Southwestern (SWNE), and Southeastern (SENE) New England English, as mapped by the Atlas of North American English, based on data from major cities.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Prof. James Stanford, a linguist at Dartmouth College, has written about how old New England accents are declining, particularly in and around Boston, as the region’s population mix changes. If that means the demise of the harsh local accent in places like South Boston, and in the crime movies that try to mimic it, it’s music to our ears. But I hope that the soft, drawling Downeast accent stays, even as represented in the over-the-top Bert & I routines.

Hit these links:

https://global.oup.com/academic/product/new-england-english-9780190625658?cc=us&lang=en&#

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tCtOZF14nTc

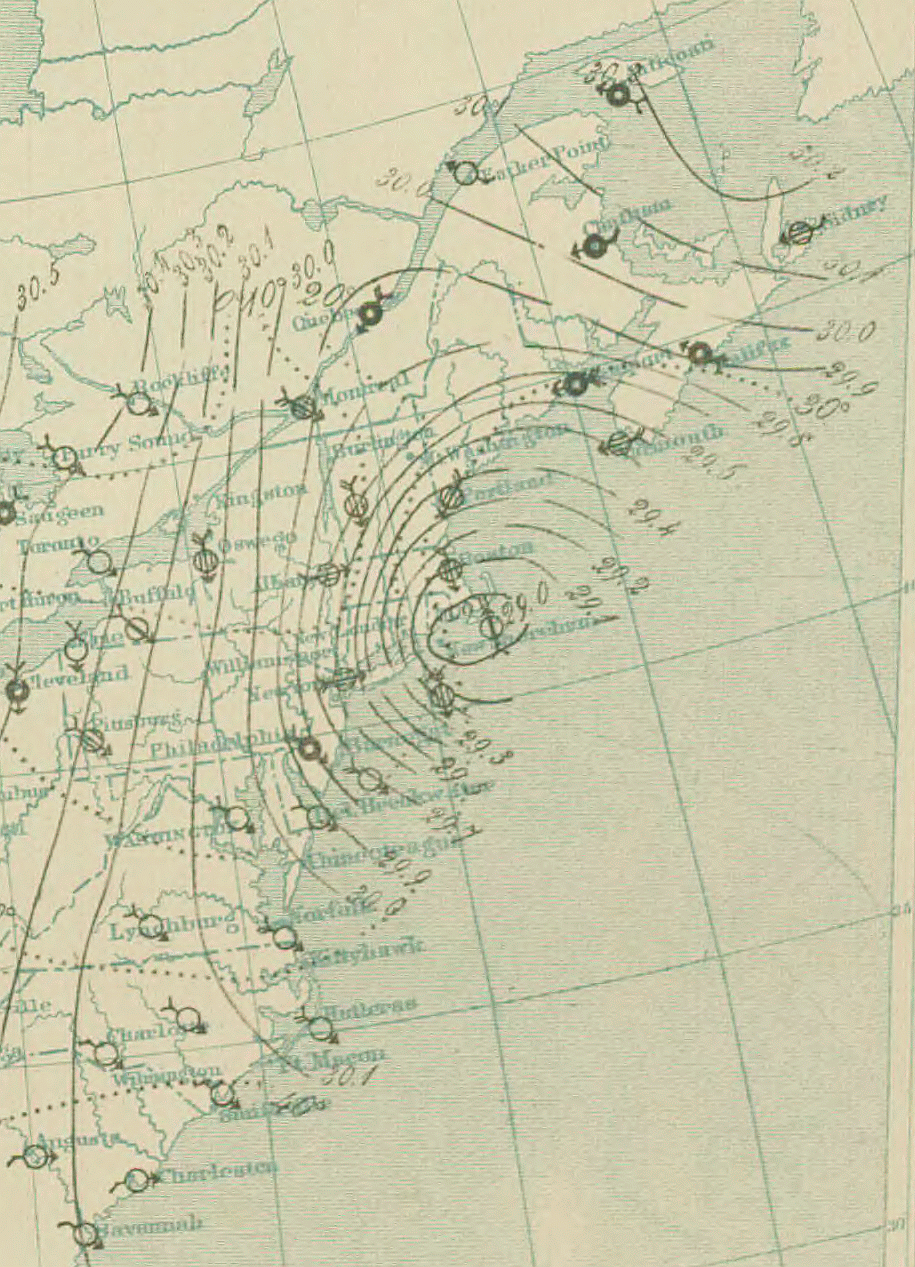

Victorian vortex

Surface weather analysis of the Great Blizzard of 1888 on March 12. For decades, that storm was the one that big Northeast snowstorms were most often compared with.

A snowdrift tunnel in Farmington, Conn., with six feet of headroom, after the Blizzard of ‘88.

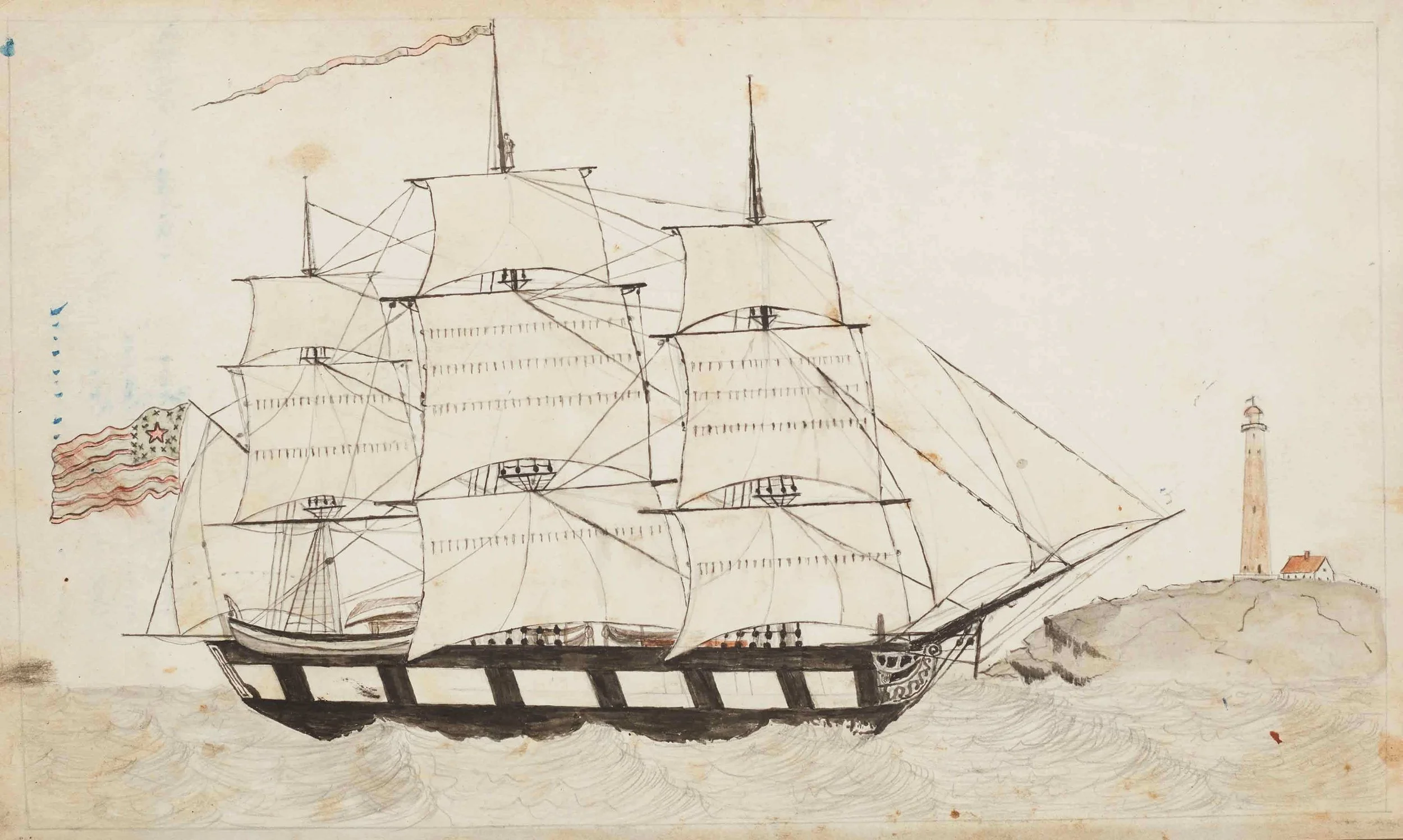

Visual arts inspired by ‘Moby Dick’

“Acushnet (Whaler),’’ from Henry M. Johnson logbook (1845-47) (ink pencil and watercolor on pencil), from the show “Call Me Ishmael: The Book Arts of Moby Dick,’’ at the Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Mass., through March 29.

Edited remarks from the museum:

“The novel (Moby Dick) and its timeless themes continue to inspire artists, designers and creatives of all types. Its first sentence: ‘Call me Ishmael,’ is one of the best-known opening lines in all of literature.

“This is the first exhibition focused on the book arts of the hundreds of editions published since 1851: the illustrations, binding designs, typography and even the physical structure….The show explores decades of creative approaches to interpreting the novel visually in book form. It will shed some light on Herman Melville’s original inspiration and include a contemporary update through recent artists’ books, graphic novels, a translation into emoji and pop-up books.’’

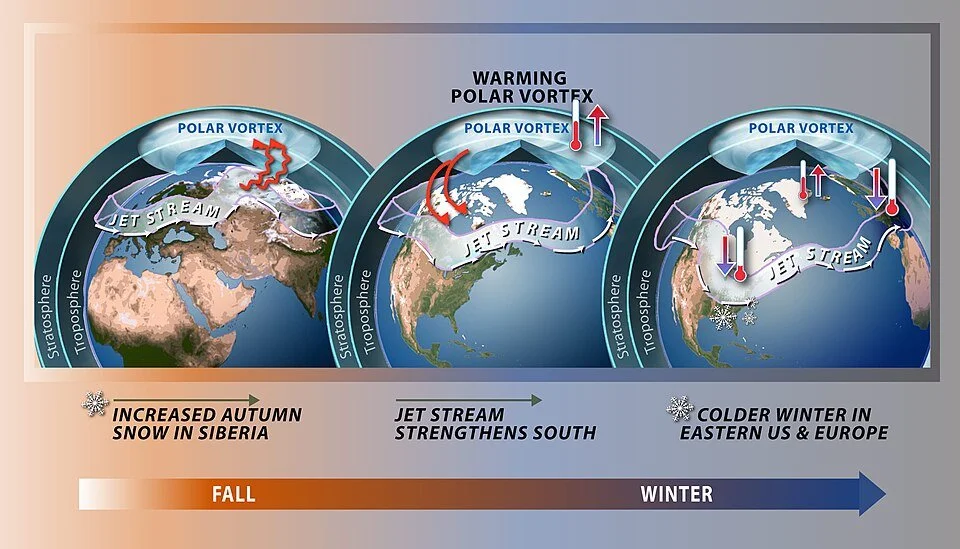

Mathew Barlow/Judah Cohen: How polar vortex from the warming Arctic and warm ocean intensified our big winter storm

From The Conversation (except for image above)

Mathew Barlow is a professor of climate science at the University of Massachusetts at Lowell.

Judah Cohen is a climate science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Mathew Barlow has received federal funding for research on extreme events and also conducts legal consulting related to climate change.

Judah Cohen does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

A severe winter storm that brought crippling freezing rain, sleet and snow to a large part of the U.S. in late January 2026 left a mess in states from New Mexico to New England. Hundreds of thousands of people lost power across the South as ice pulled down tree branches and power lines, more than a foot of snow fell in parts of the Midwest and Northeast, and many states faced bitter cold that was expected to linger for days.

The sudden blast may have come as a shock to many Americans after a mostly mild start to winter in many places in the nation, but that warmth may have partly contributed to the ferocity of the storm.

As atmospheric and climate scientists, we conduct research that aims to improve understanding of extreme weather, including what makes it more or less likely to occur and how climate change might or might not play a role.

To understand what Americans are experiencing with this winter blast, we need to look more than 20 miles above the surface of Earth, to the stratospheric polar vortex.

A forecast for Jan. 26, 2026, shows the freezing line in white reaching far into Texas. The light band with arrows indicates the jet stream, and the dark band indicates the stratospheric polar vortex. The jet stream is shown at about 3.5 miles above the surface, a typical height for tracking storm systems. The polar vortex is approximately 20 miles above the surface. Mathew Barlow, CC BY

What creates a severe winter storm like this?

Multiple weather factors have to come together to produce such a large and severe storm.

Winter storms typically develop where there are sharp temperature contrasts near the surface and a southward dip in the jet stream, the narrow band of fast-moving air that steers weather systems. If there is a substantial source of moisture, the storms can produce heavy rain or snow.

In late January, a strong Arctic air mass from the north was creating the temperature contrast with warmer air from the south. Multiple disturbances within the jet stream were acting together to create favorable conditions for precipitation, and the storm system was able to pull moisture from the very warm Gulf of Mexico.

The National Weather Service issued severe storm warnings (pink) on Jan. 24, 2026, for a large swath of the U.S. that could see sleet and heavy snow over the following days, along with ice storm warnings (dark purple) in several states and extreme cold warnings (dark blue). National Weather Service

Where does polar vortex come in?

The fastest winds of the jet stream occur just below the top of the troposphere, which is the lowest level of the atmosphere and ends about seven miles above Earth’s surface. Weather systems are capped at the top of the troposphere, because the atmosphere above it becomes very stable.

The stratosphere is the next layer up, from about seven miles to about 30 miles. While the stratosphere extends high above weather systems, it can still interact with them through atmospheric waves that move up and down in the atmosphere. These waves are similar to the waves in the jet stream that cause it to dip southward, but they move vertically instead of horizontally.

A chart shows how temperatures in the lower layers of the atmosphere change between the troposphere and stratosphere. Miles are on the right, kilometers on the left. NOAA

You’ve probably heard the term “polar vortex” used when an area of cold Arctic air moves far enough southward to influence the United States. That term describes air circulating around the pole, but it can refer to two different circulations, one in the troposphere and one in the stratosphere.

The Northern Hemisphere stratospheric polar vortex is a belt of fast-moving air circulating around the North Pole. It is like a second jet stream, high above the one you may be familiar with from weather graphics, and usually less wavy and closer to the pole.

Sometimes the stratospheric polar vortex can stretch southward over the United States. When that happens, it creates ideal conditions for the up-and-down movement of waves that connect the stratosphere with severe winter weather at the surface.

A stretched stratospheric polar vortex reflects upward waves back down, left, which affects the jet stream and surface weather, right. Mathew Barlow and Judah Cohen, CC BY

The forecast for the January storm showed a close overlap between the southward stretch of the stratospheric polar vortex and the jet stream over the U.S., indicating perfect conditions for cold and snow.

The biggest swings in the jet stream are associated with the most energy. Under the right conditions, that energy can bounce off the polar vortex back down into the troposphere, exaggerating the north-south swings of the jet stream across North America and making severe winter weather more likely.

This is what was happening in late January 2026 in the central and eastern U.S.

If climate is warming, why are we still getting severe winter storms?

Earth is unequivocally warming as human activities release greenhouse- gas emissions that trap heat in the atmosphere, and snow amounts are decreasing overall. But that does not mean severe winter weather will never happen again.

Some research suggests that even in a warming environment, cold events, while occurring less frequently, may still remain relatively severe in some locations.

One factor may be increasing disruptions to the stratospheric polar vortex, which appear to be linked to the rapid warming of the Arctic with climate change.

The polar vortex is a strong band of winds in the stratosphere, normally ringing the North Pole. When it weakens, it can split. The polar jet stream can mirror this upheaval, becoming weaker or wavy. At the surface, cold air is pushed southward in some locations. NOAA

Additionally, a warmer ocean leads to more evaporation, and because a warmer atmosphere can hold more moisture, that means more moisture is available for storms. The process of moisture condensing into rain or snow produces energy for storms as well. However, warming can also reduce the strength of storms by reducing temperature contrasts.

The opposing effects make it complicated to assess the potential change to average storm strength. However, intense events do not necessarily change in the same way as average events. On balance, it appears that the most intense winter storms may be becoming more intense.

A warmer environment also increases the likelihood that precipitation that would have fallen as snow in previous winters may now be more likely to fall as sleet and freezing rain.

Still many questions

Scientists are constantly improving the ability to predict and respond to these severe weather events, but there are many questions still to answer.

Much of the data and research in the field relies on a foundation of work by federal employees, including government labs like the National Center for Atmospheric Research, known as NCAR, which has been targeted by the Trump administration for funding cuts. These scientists help develop the crucial models, measuring instruments and data that scientists and forecasters everywhere depend on.

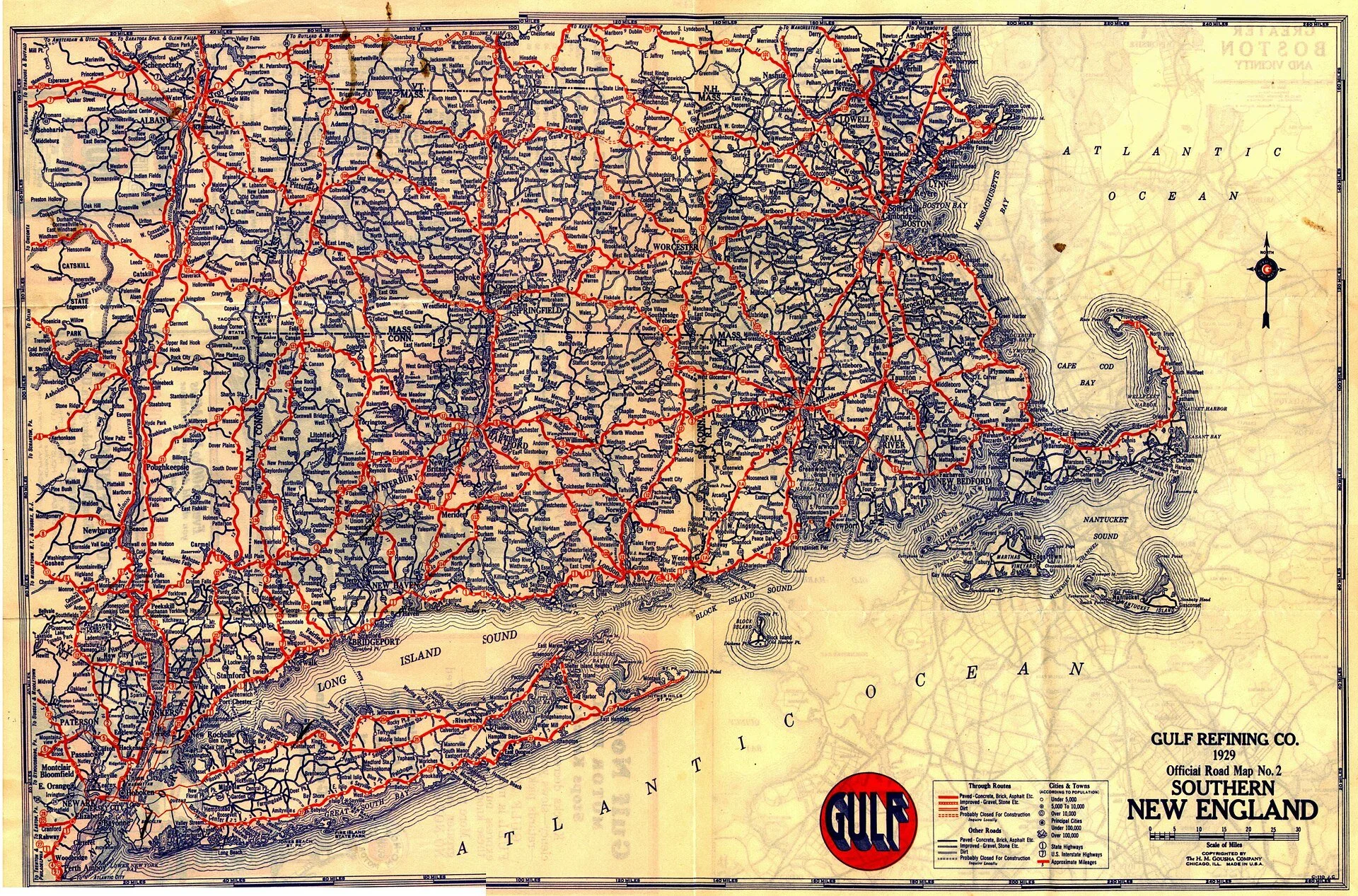

1929: Drive to the poorhouse in your own automobile

For Sunday drivers with chains on their tires.

‘Share what sustains us’

Poster for “InGathering” show at the University of New Hampshire Gallery of Art, Durham, N.H., through March 27.

The gallery says:

“There is a season for all things, and every season has its purpose. During this fallow season of winter, we gather for sustenance and warmth. We gather nuts and grains. We gather songs and stories. We gather memories. We gather light and color. We gather together for warmth and to share what sustains us.’’

‘Silence never won rights’

In the National Archives, in Washington, D.C., where the Constitution (including the Bill of Rights), the Declaration of Independence and other American founding documents are exhibited.

“So long as we have enough people in this country willing to fight for their rights, we’ll be called a democracy.’’

“Silence never won rights. They are not handed down from above; they are forced by pressures from below.’’

“The rule of law in place of force, always basic to my thinking, now takes on a new relevance in a world where, if war is to go, only law can replace it.’’

— Roger Nash Baldwin (1884-1961), Wellesley, Mass., native who co-founded the American Civil Liberties Union.

Electric impulses

From Kate Henderson’s show “Electric Current,’’ at KLG/Kehler Liddell Gallery, New Haven, Conn., through Feb. 1

She says:

“As a creator, my impulses embody both a deep appreciation of nature as it exists, and an ever-present yearning for an ecstatic state. Aiming to bridge and ultimately reconcile these dualities, my work stands in subtle resistance against fundamentalism of all kinds, favoring an endless search for meaning across complex, multiple worlds.’’

Chris Powell: Conn. governor’s ‘unfinished business’ needn’t wait

Connecticut Capitol, in Hartford. “The Nutmeg State’’ has always been among the richest states.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Being governor is a tough job, especially in Connecticut, where thousands have their hands out and the more they're given, the more they want and expect. The state has not prospered particularly during Ned Lamont's two terms, but given his party's ravenous constituencies, things probably would be worse under any other Democrat. Lamont has restrained spending and taxes more than the big Democratic majorities in the General Assembly would have liked.

But state government remains poorly managed and in some cases not managed at all, as was suggested by the audit released this week by the state Economic and Community Development Department about corruption in “anti-poverty" grants that the department administered only nominally. The grants were actually controlled by state Sen. Douglas McCrory, D-Hartford, who routed them through a special friend who, the audit found, took a lot of the money for herself in the guise of providing services not actually rendered.

The governor quickly tried to take ownership of the audit, joining in its announcement. He called it “a strong reminder that when taxpayer dollars are involved, we have zero tolerance for fraud, waste, or mismanagement."

This was nonsense, for such grants have been routinely allocated to Democratic state legislators as raw patronage without oversight or evaluation of results. The governor has gone along with this. The corruption exposed by the audit is a matter of his own indifference and the negligence of his economic development commissioner.

The governor said Senator McCrory should “step back" from Senate business but didn't propose to stop the patronage grants.

And are Connecticut's cities any less poor for the grants, or less poor for any “anti-poverty" programs? Is poverty any less of a patronage business?

In a recent interview with the Connecticut Examiner, Lamont said he was glad to answer for his record and, if elected to the third term he seeks, will address “some unfinished business."

Where to begin? And why wait?

Given the terrible cold descending on the state this weekend, “unfinished business" -- unstarted, really -- could begin with the “cold weather protocol" the governor has invoked. This happens when state government and social-service agencies summon the mentally ill off the streets at night to various overcrowded indoor facilities and send them back outside in the morning in state government's belief that the best therapy for mental illness is fresh air.

More than a hundred of them have died outdoors in Connecticut in the last year.

For decades this therapy has saved state government millions of dollars on mental hospitals, money spent instead on state employee raises and pensions.

Always needing urgent review is the Correction Department. Two Fridays ago the General Assembly's Judiciary Committee held a hearing about the department's chronic management failures, starting with the report issued by the state auditors last July showing that 15 of the 18 failures cited by the audit were cited by previous audits as well. The new audit found that the department lately had paid more than $800,000 in salaries for excessive administrative leave.

Two weeks ago the state inspector general concluded that the deaths of two inmates at the state prison in Newtown within days of each other in 2024 were caused by mistakes with medication administered by medical contractors. This week the department's ombudsman issued a report criticizing not only inadequate medical care for prisoners, a longstanding issue, but also unsanitary conditions and excessive lockdowns.

The correction commissioner said again that the department aims to do better, so that will suppress the issue for another year, since nobody cares much about prisoners besides the ombudsman, whose appointment the governor obstructed.

As for state taxes, however well the governor has restrained them, much of that restraint has always been achieved by pushing what probably should be state expenses down to the municipal level, where they are recovered through higher property taxes, though Connecticut's property taxes are disgracefully high.

For many years that too has been “unfinished business."

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

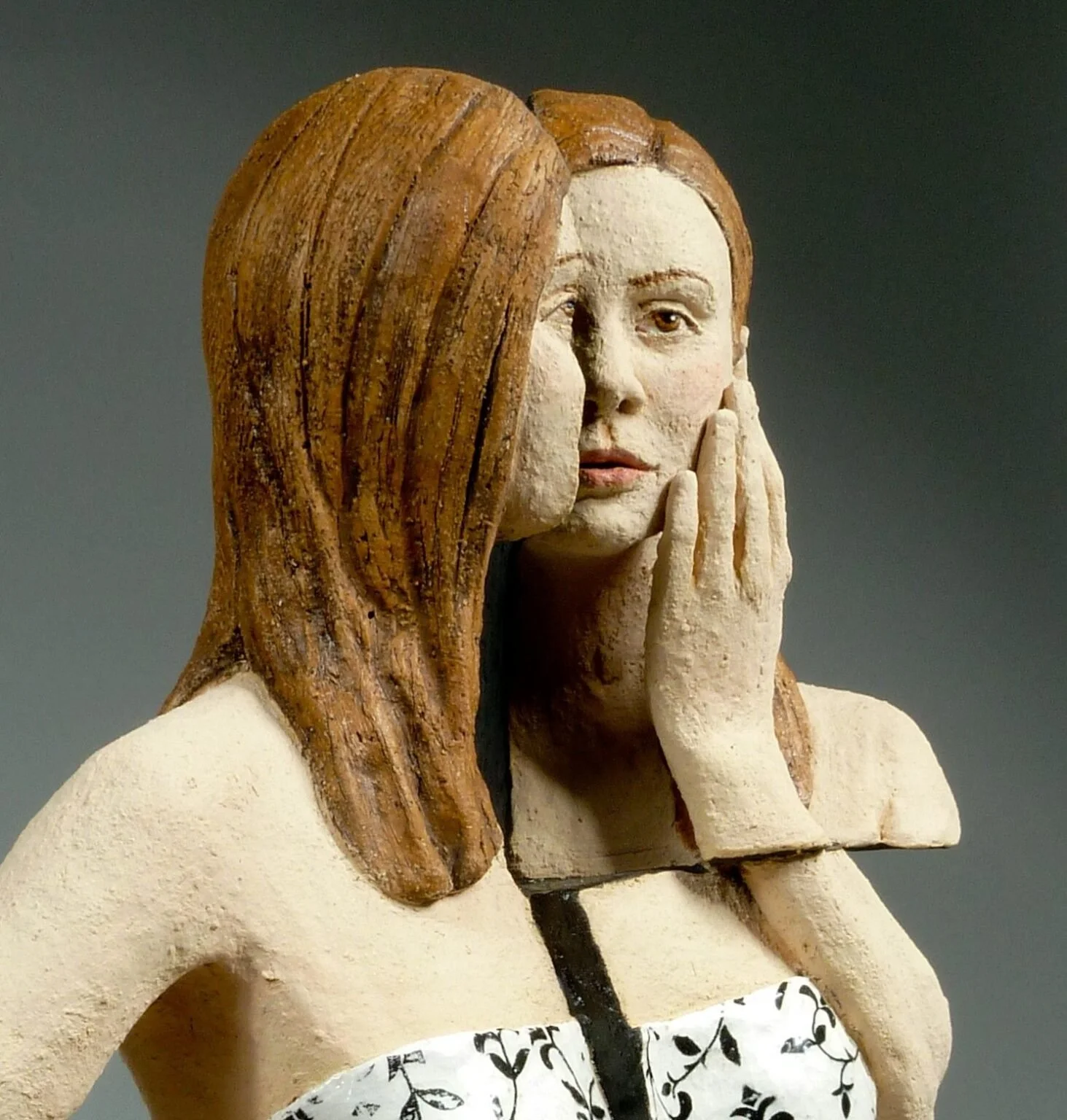

More than just me

“Hush” (ceramic), by Delanie Kabrick Wise, at Boston Sculptors Gallery.

She says:

“When making figurative work, the pieces always end up being a kind of self portrait, not in the literal sense, but they reflect my sensibilities. It used to bother me that this happened, but now I accept this reality and embrace it. I am the person that I know the best and I feel my life experiences are not so unique as they are universal.’’

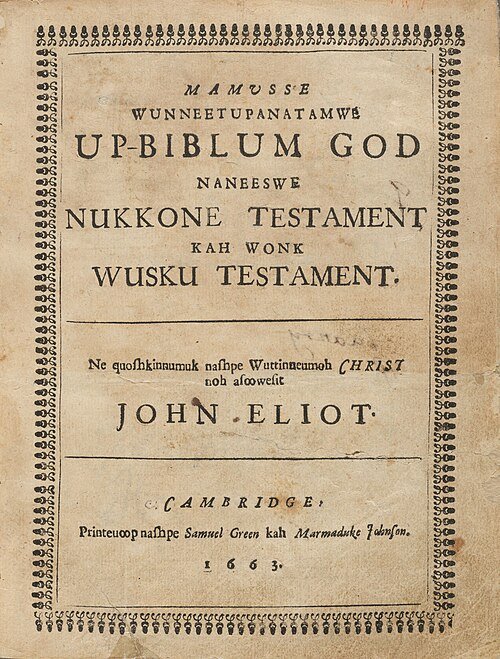

Llewellyn King: Check the Bible on citizenship and rights

The Eliot Indian Bible was the first translation of the Christian Bible into an indigenous American language, as well as the first Bible published in British North America. It was prepared by English Puritan missionary to New England John Eliot by translating the Geneva Bible.

About 40 exist today out of the original 1,050 printed, with about 30 in New England (libraries and private collections) and about 10 in Europe.

A Gutenberg Bible (1455) at the New York Public Library.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

President Donald Trump claims that birthright citizenship isn’t that: a birthright. He wants the authority to revoke the citizenship of U.S.-born children of both immigrants here illegally and visitors here only temporarily.

The Supreme Court will hear arguments on birthright citizenship this spring. It will likely hand down a ruling by summer.

Before the justices decide, they may want to cast their eyes over the Acts of the Apostles in the Bible.

They will learn anew how inviolate birthright citizenship was to Paul when he entered Jerusalem. He had to invoke his Roman citizenship to save himself from flogging and torture.

On another occasion, Paul used his rights as a citizen to demand a trial.

Here is what befell Paul in Jerusalem in Acts 22:29:

22 The crowd listened to Paul until he said this. Then they raised their voices and shouted, “Rid the earth of him! He’s not fit to live!”

23 As they were shouting and throwing off their cloaks and flinging dust into the air, 24 the commander ordered that Paul be taken into the barracks. He directed that he be flogged and interrogated in order to find out why the people were shouting at him like this.

25 As they stretched him out to flog him, Paul said to the centurion standing there, “Is it legal for you to flog a Roman citizen who hasn’t even been found guilty?”

26 When the centurion heard this, he went to the commander and reported it. “What are you going to do?” he asked. “This man is a Roman citizen.”

27 The commander went to Paul and asked, “Tell me, are you a Roman citizen?”

“Yes, I am,” he answered.

28 Then the commander said, “I had to pay a lot of money for my citizenship.”

“But I was born a citizen,” Paul replied.

29 Those who were about to interrogate him withdrew immediately. The commander himself was alarmed when he realized that he had put Paul, a Roman citizen, in chains.

In the 1st Century A.D., Roman citizenship could be had by birth, purchased or granted by the emperor. But citizens who were born to their status had something of an edge over those, like the commander, who had bought their citizenship.

A Roman citizen enjoyed many rights, which are also contained in the U.S. Constitution but are being ignored by Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents who are sweeping up people — some have turned out to be citizens and some have been deported in error.

These are the rights of a Roman citizen in the 1st Century A.D.:

Immunity from flogging and torture. These could be used to extract confessions, but were forbidden to be used against citizens.

The right to a fair trial, which included the accused’s right to confront his accusers.

The right to appeal directly to the emperor.

Protection from degrading death, particularly crucifixion.

Protection from illegal imprisonment. A citizen couldn’t be jailed if he hadn’t been convicted.

Trump is seeking a Supreme Court ruling to uphold his executive order (14161), ending universal birthright citizenship. The lower courts have restricted the order, and the president has asked SCOTUS to set that aside.

The 14th Amendment grants birthright citizenship to any child born under the jurisdiction of the United States. But Trump’s executive order, according to the New York City Bar, “purports to limit birthright citizenship by alleging that a child born to undocumented parents is not ‘within the jurisdiction of the United States.’

“It thereby posits that birthright citizenship does not extend to any child born in the United States to a mother who is unlawfully present or lawfully present on a temporary basis and a father who is neither a U.S. citizen nor a lawful permanent resident.”

If Trump prevails, the unfortunate children will be unable to get birth certificates, register for school, receive health care or any kind of public assistance. They must either seek citizenship from their parents’ country or, more likely, join the growing ranks of the world’s stateless people, punished for life for the crime of being born. Victims to be exploited down through the decades of their lives.

The United Nations estimates that there are more than 4 million stateless people in the world, but that is a gross undercount, considering the number of refugees across Africa and in Latin America. War and drought are adding to the numbers daily.

If the justices want another biblical example, they may turn to the Old Testament and its several warnings that the sins of the fathers will be visited on the children for generations. As Exodus 20:5 puts it, “visiting the iniquity of the fathers on the children and the children's children to the third and fourth generation.”

Those who support the Trump view may want to think about the iniquity they are promoting. No baby chooses where to be born, ever.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS, and an international energy-sector consultant. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com ,and he’s based inRhode Island.

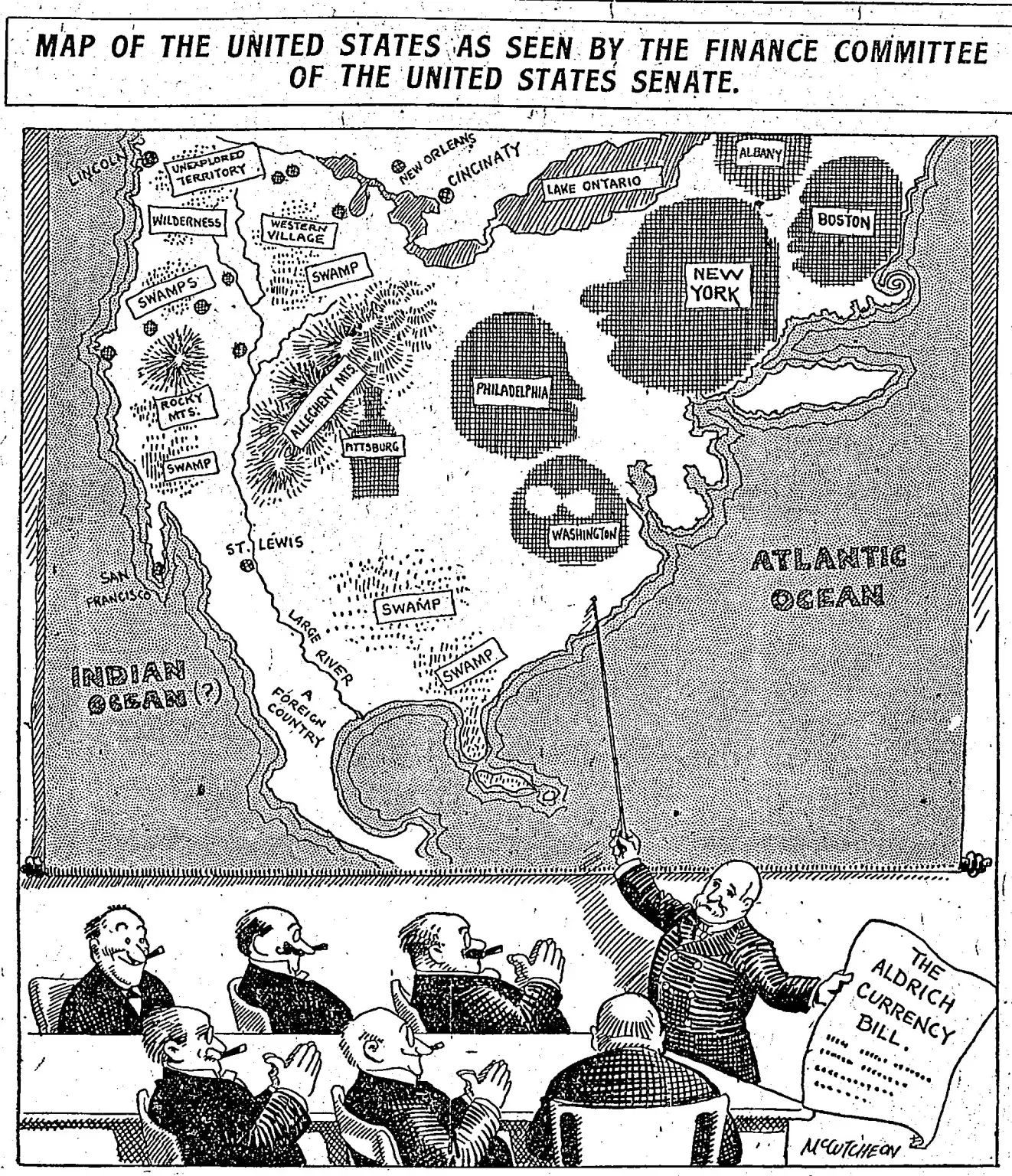

A moneyed perspective

The Aldrich referred to in this 1908 cartoon is powerful Sen. Nelson Aldrich of Rhode Island, (1841-1915) dubbed “The General Manager of the Nation.”

The cartoon is by John McCutcheon (1870-1949), the Pulitzer Prize-winning cartoonist for the Chicago Tribune, which printed his cartoons on the front page for 40 years. He was known as the “dean of American cartoonists.”