Vox clamantis in deserto

Switching to regionally based energy looking better than ever

Balcony solar panels

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Anything that New Englanders can do to achieve more regional energy independence would be most appreciated! As I have written, one such way is to promote use of those small “plug-in’’ solar-energy devices in rapidly growing use elsewhere, notably on European balconies. The units range from 200 to 1,200 watts.

Unfortunately, such solar is not yet widely legalized or standardized in Rhode Island, though there’s been legislation this year to do so, which would involve adjusting to utility codes and local regulations. Rhode Island does have a streamlined permitting process for larger, mounted systems for roofs and yards. Small-scale solar is in a legal gray area in Massachusetts, too.

Stop sending so much of our energy dollars to Pennsylvania and points southwest for polluting and Earth-cooking fossil-fuel companies! Let’s cut our electricity costs and reduce the stress on the regional grid – especially in cold waves and heat waves. Oh yes, and revive nuclear energy. With ever more efficient solar and wind power, and rapidly improving battery storage, the urgency to move from dirty and expensive fuel is ever more obvious.

And those New Englanders who havw lost power in this week’s historic southern New England blizzard might consider how much better off they’d be if their dwellings had solar power today,

Let the big melt set them free

“Abundant” (oil on canvas), by Davis Lloyd Brown, in his show “Paintings and Drawings from the Primordial Soup Series,’’ in The Gallery at the First Church Boston Unitarian Universalist.

He says:

“I was channeling Picasso, and Klimt came out,” in his drawings and large-scale paintings using templates inspired by timeless images, symbols and patterns.

Nir Eisikovits/Jacob Burley: What’s the purpose of Universities in the world of AI?

Open AI logo.

The old-fashioned place to write exam answers.

BOSTON

From The Conversation, except for images above.

Nir Eisikovits is a professor of philosophy, and director of the Applied Ethics Center of the University of Massachusetts at Boston, where Jacob Burley is a research fellow.

Public debate about artificial intelligence in higher education has largely orbited a familiar worry: cheating. Will students use chatbots to write essays? Can instructors tell? Should universities ban the tech? Embrace it?

These concerns are understandable. But focusing so much on cheating misses the larger transformation already underway, one that extends far beyond student misconduct and even the classroom.

Universities are adopting AI across many areas of institutional life. Some uses are largely invisible, such as systems that help allocate resources, flag “at-risk” students, optimize course scheduling or automate routine administrative decisions. Other uses are more noticeable. Students use AI tools to summarize and study, instructors use them to build assignments and syllabuses and researchers use them to write code, scan literature and compress hours of tedious work into minutes.

People may use AI to cheat or skip out on work assignments. But the many uses of AI in higher education, and the changes they portend, beg a much deeper question: As machines become more capable of doing the labor of research and learning, what happens to higher education? What purpose does the university serve?

Over the past eight years, we’ve been studying the moral implications of pervasive engagement with AI as part of a joint research project between the Applied Ethics Center at UMass Boston and the Institute for Ethics and Emerging Technologies. In a recent white paper, we argue that as AI systems become more autonomous, the ethical stakes of AI use in higher ed rise, as do its potential consequences.

As these technologies become better at producing knowledge work – designing classes, writing papers, suggesting experiments and summarizing difficult texts – they don’t just make universities more productive. They risk hollowing out the ecosystem of learning and mentorship upon which these institutions are built, and on which they depend.

Nonautonomous AI

Consider three kinds of AI systems and their respective impacts on university life:

AI-powered software is already being used throughout higher education in admissions review, purchasing, academic advising and institutional risk assessment. These are considered “nonautonomous” systems because they automate tasks, but a person is “in the loop” and using these systems as tools.

These technologies can pose a risk to students’ privacy and data security. They also can be biased. And they often lack sufficient transparency to determine the sources of these problems. Who has access to student data? How are “risk scores” generated? How do we prevent systems from reproducing inequities or treating certain students as problems to be managed?

These questions are serious, but they are not conceptually new, at least within the field of computer science. Universities typically have compliance offices, institutional review boards and governance mechanisms that are designed to help address or mitigate these risks, even if they sometimes fall short of these objectives.

Hybrid AI

Hybrid systems encompass a range of tools, including AI-assisted tutoring chatbots, personalized feedback tools and automated writing support. They often rely on generative AI technologies, especially large language models. While human users set the overall goals, the intermediate steps the system takes to meet them are often not specified.

Hybrid systems are increasingly shaping day-to-day academic work. Students use them as writing companions, tutors, brainstorming partners and on-demand explainers. Faculty use them to generate rubrics, draft lectures and design syllabuses. Researchers use them to summarize papers, comment on drafts, design experiments and generate code.

This is where the “cheating” conversation belongs. With students and faculty alike increasingly leaning on technology for help, it is reasonable to wonder what kinds of learning might get lost along the way. But hybrid systems also raise more complex ethical questions.

If students rely on generative AI to produce work for their classes, and feedback is also generated by AI, how does that affect the relationship between student and professor? Eric Lee for The Washington Post via Getty Images

One has to do with transparency. AI chatbots offer natural-language interfaces that make it hard to tell when you’re interacting with a human and when you’re interacting with an automated agent. That can be alienating and distracting for those who interact with them. A student reviewing material for a test should be able to tell if they are talking with their teaching assistant or with a robot. A student reading feedback on a term paper needs to know whether it was written by their instructor. Anything less than complete transparency in such cases will be alienating to everyone involved and will shift the focus of academic interactions from learning to the means or the technology of learning. University of Pittsburgh researchers have shown that these dynamics bring forth feelings of uncertainty, anxiety and distrust for students. These are problematic outcomes.

A second ethical question relates to accountability and intellectual credit. If an instructor uses AI to draft an assignment and a student uses AI to draft a response, who is doing the evaluating, and what exactly is being evaluated? If feedback is partly machine-generated, who is responsible when it misleads, discourages or embeds hidden assumptions? And when AI contributes substantially to research synthesis or writing, universities will need clearer norms around authorship and responsibility – not only for students, but also for faculty.

Finally, there is the critical question of cognitive offloading. AI can reduce drudgery, and that’s not inherently bad. But it can also shift users away from the parts of learning that build competence, such as generating ideas, struggling through confusion, revising a clumsy draft and learning to spot one’s own mistakes.

Autonomous agents

The most consequential changes may come with systems that look less like assistants and more like agents. While truly autonomous technologies remain aspirational, the dream of a researcher “in a box” – an agentic AI system that can perform studies on its own – is becoming increasingly realistic.

Growing sophistication and autonomy of technology systems means that scientific research can increasingly be automated, potentially leaving people with fewer opportunities to gain skills practicing research methods. NurPhoto/Getty Images

Agentic tools are anticipated to “free up time” for work that focuses on more human capacities like empathy and problem-solving. In teaching, this may mean that faculty may still teach in the headline sense, but more of the day-to-day labor of instruction can be handed off to systems optimized for efficiency and scale. Similarly, in research, the trajectory points toward systems that can increasingly automate the research cycle. In some domains, that already looks like robotic laboratories that run continuously, automate large portions of experimentation and even select new tests based on prior results.

At first glance, this may sound like a welcome boost to productivity. But universities are not information factories; they are systems of practice. They rely on a pipeline of graduate students and early-career academics who learn to teach and research by participating in that same work. If autonomous agents absorb more of the “routine” responsibilities that historically served as on-ramps into academic life, the university may keep producing courses and publications while quietly thinning the opportunity structures that sustain expertise over time.

The same dynamic applies to undergraduates, albeit in a different register. When AI systems can supply explanations, drafts, solutions and study plans on demand, the temptation is to offload the most challenging parts of learning. To the industry that is pushing AI into universities, it may seem as if this type of work is “inefficient” and that students will be better off letting a machine handle it. But it is the very nature of that struggle that builds durable understanding. Cognitive psychology has shown that students grow intellectually through doing the work of drafting, revising, failing, trying again, grappling with confusion and revising weak arguments. This is the work of learning how to learn.

Taken together, these developments suggest that the greatest risk posed by automation in higher education is not simply the replacement of particular tasks by machines, but the erosion of the broader ecosystem of practice that has long sustained teaching, research and learning.

An uncomfortable inflection point

So what purpose do universities serve in a world in which knowledge work is increasingly automated?

One possible answer treats the university primarily as an engine for producing credentials and knowledge. There, the core question is output: Are students graduating with degrees? Are papers and discoveries being generated? If autonomous systems can deliver those outputs more efficiently, then the institution has every reason to adopt them.

But another answer treats the university as something more than an output machine, acknowledging that the value of higher education lies partly in the ecosystem itself. This model assigns intrinsic value to the pipeline of opportunities through which novices become experts, the mentorship structures through which judgment and responsibility are cultivated, and the educational design that encourages productive struggle rather than optimizing it away. Here, what matters is not only whether knowledge and degrees are produced, but how they are produced and what kinds of people, capacities and communities are formed in the process. In this version, the university is meant to serve as no less than an ecosystem that reliably forms human expertise and judgment.

In a world where knowledge work itself is increasingly automated, we think that universities must ask what higher education owes its students, its early-career scholars and the society it serves. The answers will determine not only how AI is adopted, but also what the modern university becomes.

The romance of Lowell

Seal of the City of Lowell, one of the first great textile-manufacturing towns in America.

Pawtucket Canal at Central Street looking west, in Lowell. The 19th Century textile mills have been converted to other uses, if not torn down,

-Photo by John Phelan

“A golden Byzantine dome rises from the roofs along the canal, a Gothic copy of Chartres arises from the slums of Moody Street, little children speak French, Greek, Polish, and even Portuguese on their way to school. And I have a recurrent dream of simply walking around the deserted twilight streets of Lowell in the mist, eager to turn every known and fabled corner…it always makes me happy when I wake up.’’

— Jack Kerouac (1922-1969), American novelist and poet and Lowell native

Beauty and work

“Snowbound,’’ by N.C. Wyeth (1882-1945), a famed painter and illustrator who grew up on a farm in Needham, Mass.

Drawing Presidential lines

“George Washington’’ (1968) and “Abraham Lincoln”(1968), (both ink on paper), in the show “Oscar Berger Presidential Portraits”, at the New Britain (Conn.) Museum of American Art, through Aug. 30.

The museum says:

“Internationally acclaimed as ‘the greatest caricaturist of world celebrities,’ Oscar Berger (1901–1997) depicted the ‘Who’s Who” of world history throughout his career.

“Born in 1901 in Czechoslovakia, Berger became a cartoonist in Prague, before moving to New York, where his work appeared in leading publications, including The New York Times, Life, and the New York Herald Tribune. Following in the tradition of other notable caricaturists, such as Thomas Nast (1840–1902) and Georges Goursat (1863–1934), Berger aimed to capture the likeness and character of his models and to distill and exaggerate their ‘essence.’

“In 1968, Berger embarked on an ambitious project to depict our nation’s presidents, from Washington to Nixon. His presidential caricatures are distinct in style and technique, however, in that they are each made with one continuous line. As Berger himself explained, ‘through the bearded and the cleanjowled, the somber and the sly, the able and the not-so-able; the line flows along, endlessly witnessing the persistence of the American consensus.’ For Berger, an imaginary line connected each drawing, encompassing all of the presidents and symbolically representing the continuous history of American leadership. Saturated with wisdom and wit, Berger’s portraits aim to entertain while also conjuring the personalities and legacies of the American presidents.’’

Dump snow on Boston Sidewalks? Sure

In Boston’s Back Bay.

From The Boston Guardian. This article, slightly edited for New England Diary, is by Daniel Larlham Jr.

(Robert Whitcomb, New England Diary’s publisher/editor, is chairman of The Boston Guardian.)

There are only so many places for the accumulated snow to go as Boston waits for it to melt away, Back Bay resident Martyn Roetter was quite perturbed to hear from a neighbor in the early morning of Feb. 13 that snow-removal contractors were clearing the snow from the bike lane and onto the sidewalk in front of their Beacon Street building.

Cyclists have recently expressed frustration over the lack of clear bike lanes across the city, with some going as far as clearing the lanes themselves.

But Roetter, who recently stepped down as chair of the Neighborhood Association of the Back Bay and remains a member, says he was surprised to hear from his neighbor of 20 years that snow was being moved into the already cleared sidewalk path.

When asked by the neighbor, Roetter alleges, the workers claimed that they were contracted by the city. The neighbor was able to convince the crew to re-clear the snow from the sidewalk paths.

“Why would you clear snow from the bike lanes, which are hardly used at all of course at this time of year and certainly not under the snowy conditions that still prevail, why would you take snow from that and dump it from sidewalks which had been cleared?” Roetter added.

Later in the day Roetter took stock of several Beacon Street blocks from Clarendon Street onwards and noted that the bike lane had been cleared as well, with the snow moved to the sidewalk snowbanks, and not the paths.

“I think it’s important that we provide residents with the most professional snow-removal process as we can to ensure residents are safe crossing our streets and walking our sidewalks, especially persons with disabilities, our seniors and young children going to school,” said City Councilor Ed Flynn, who represents part of the Back Bay. “It’s about public safety. It’s about quality of life for all of residents.”

Flynn added that so far this year, the rank-and-file public-works team did the best job that they could at snow removal under difficult circumstances.

“However, I don’t believe the mayor’s office and the city council provided the critical support to effectively remove the snow. Leadership is about accepting responsibility, and that responsibility rests squarely with the mayor and the city council.”

Others have been quite pleased with the city’s snow-removal efforts this year (at least before the Feb. 22-23 storm), Meg Mainzer-Cohen, president of the Back Bay Association, said that this year’s plowing and continued snow removal have been superior.

“What we saw in the Back Bay, sort of the business portion of Back Bay, was the prioritizing of and the full clearing of travel lanes.

The way we saw that function, was there was capacity for vehicles to be able to function in the Back Bay in a way that was far superior, than say, the last few years.”

Mainzer-Cohen explained that as a kind of step one in the snow-removal process. The next was to triage and remove some of the large and problematic snow piles that accumulated.

On Berkely Street, Mainzer-Cohen said that there had been signs posted less than a week after the original plowing notifying of additional snow removal. Later, the snow in the bike lanes had been removed.

She added that if any snow had been spillover into the already clear sidewalks paths, it was likely done by mistake.

“The snow is going somewhere, and there can be inadvertent placement of snow in a place that had been shoveled. Really, the whole goal is to hit all these marks.”

The mayor’s press office did not respond to requests for comments by deadline on whether bike-lane clearing was a current priority for the administration or if contractors had been instructed to clear snow onto the sidewalks.

Daniel Larlham Jr. reports for The Boston Guardian.

In Bristol, artists from around America reflect on the nation’s 250th anniversary

The Bristol (R.I.) Art Museum presents a national exhibition titled “When in the Course of Human Events,’’ Feb. 22-April 10, featuring works by 65 artists from across America marking the 250th anniversary of the United States,.

— Work by Nancy Whitcomb

The museum says:

”This exhibition invites artists to reflect on what follows the iconic opening line of the Declaration of Independence, exploring what it means to experience human events in our contemporary world.’’

“The exhibition was juried by Meredith Stern, a printmaker, publisher and socially engaged artist. Her work has been featured in large-scale installations nationally and internationally, and is included in the collections of the Library of Congress, RISD Museum, MoMA, and the Obama Presidential Museum.’’

Nancy Whitcomb writes of her work above:

“My piece, ‘The Spirit of ‘76’ (detail here) is made from the cover and ripped out pages of an old American history book. Old pages were turned into shapes and covered with blue and red encaustic paint. This is my shrine to the democracy we are losing.’’

A dream of the woods

“WABANAVIA’’ (digital film), by Jason Brown, at the Farnsworth Art Museum, Rockland, Maine.

In the dreamscape video Wabanavia, Brown, with Maine Wabanaki and Swedish backgrounds, serves as the lead protagonist who explores familiar yet fantastical environs that draw upon his personal heritage, traditional Wabanaki greeting songs, Scandinavian musical notes and Norse mythology.

Chris Powell: The $45 million Randy Cox case displays Contradiction of Two political Principles in Connecticut

MANCHESTER, Conn.

While there was plenty of negligence in the case of Randy Cox, the man who was paralyzed after his arrest by New Haven police in 2022, the court decision concluding the case's criminal aspects suggests that the negligence really wasn't that of the officers it was blamed on.

Cox had gotten drunk and was holding a bottle of liquor and brandishing a gun he carried illegally as he walked past a street fair, scaring people, one of whom called the cops. They arrested him and put him into a van for transport to the police station. Inside the van he resisted arrest, yelled, kicked, and rolled on the floor before sitting on the van's bench. But the bench had no seatbelts and when the driver stopped hard to avoid a collision, Cox slid head-first to the wall at the front of the passenger compartment, breaking his neck.

Rather than wait for an ambulance, the officer driving the van continued to the station, where other officers didn't believe Cox's protests that he couldn't move. They figured he was just drunk and faking injury, so they manhandled him into a wheelchair and then into a cell before medical help arrived.

Since Cox is Black, New Haven and then the country were filled with shrieks of racism as his catastrophic injury became clear, though most of the officers who handled him after his arrest were also members of minority groups. Mayor Justin Elicker, who is white and whose city is two-thirds minority, was quickly intimidated out of treating the situation honestly. Scapegoats were needed to calm the political controversy.

Fortunately for the mayor, five officers were soon charged criminally. Two pleaded guilty in plea bargains -- one of them was fired and lost her appeal for reinstatement and the other retired. The remaining three insisted on innocence and this month were more or less vindicated. Superior Court Judge David Zagaja granted them "accelerated rehabilitation," a probation that dismisses charges, ruling that the officers had not meant to hurt Cox and had not caused his catastrophic injury.

Impartial observers could have seen as much long before now. The city's responsibility for Cox's injury was entirely a matter of the failure to install seatbelts in the prisoner transport van, a failure dating back many years, a failure for which New Haven and its insurance company have paid Cox and his racism-contriving "civil-rights" lawyer $45 million, which, it is hoped, will cover the lifetime care Cox is likely to need.

While politically correct Connecticut may not be able to acknowledge it, the heavier responsibility here falls on Cox himself. Getting drunk in public is never a good idea. Getting drunk, carrying a gun illegally, and brandishing it at a street fair, scaring people and compelling police to arrest you, is a worse idea.

Of course no one is paying more for his mistake than Cox himself, but if he had been white and a member of the National Rifle Association, he might not have been forgiven as quickly he was, with the criminal charges against him dropped because of his injury and the mayor, still playing politics, treating him as an innocent who was persecuted by the police.

As for the three officers who now have beaten the criminal charges against them, all were fired but one regained his job through an appeal and the two others continue their appeals.

Mayor Elicker says he disagrees with the judge's decision to dismiss the charges against the three officers, so presumably he will continue to oppose reinstating the two still appealing. But a fairer resolution would be a settlement reinstating them with less than full back pay in recognition that for three years they have suffered far out of proportion to whatever they did wrong.

All this leaves political liberalism in Connecticut to sort out the wonderful contradiction of its two silliest principles: that minorities are always right, and so are members of government-employee unions.

-----

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

-

Sonali Kolhatkar: The big abusers are Trump and other rich and Powerful Men connected with Epstein, not migrants, etc.

“Best Friends Forever” (also known as “Why Can't We Be Friends?”’) statue of Donald Trump and Jeffrey Epstein, briefly installed at the National Mall in downtown Washington, D.C., last Sept. The Feds took it down.

Via OtherWords.org

Atty. Gen. Pam Bondi’s contentious House hearing about the Justice Department’s handling of the Epstein files offered a clear message to the nation: sex trafficking of women and minors is perfectly acceptable as long as wealthy white men do it.

Jeffrey Epstein, the disgraced late sex trafficker, fixer, and political networker, was found to have ties to huge number of the world’s elites on both sides of the political aisle — including Elon Musk, Peter Thiel, Ehud Barak, Bill Gates, Steve Bannon, Larry Summers, Bill Clinton, and of course, Donald Trump.

For years, Trump’s conservative backers have attacked LGBTQ+ people, drag queens, immigrants, and others, claiming a desire to protect women and children from rapists and groomers. Trump even boasted that “whether the women liked it or not,” he would “protect” them from migrants, whom he slandered as “monsters” who “kidnap and kill our children.”

But when given the opportunity to seek justice for countless women and children who were trafficked, abused, and exploited by the world’s wealthiest, most powerful people, the MAGA movement and its leaders have shown a startling disinterest in accountability. During her hearing Bondi tried desperately to deflect attention, claiming that the stock market was more deserving of public attention than Epstein’s victims.

Even the Republican rank and file is now mysteriously detached from the Epstein files.

Polls show that in summer 2025, 40 percent of GOP voters disapproved of the federal government’s handling of the Epstein files. But by January 2026, only about half that percentage disapproved — even after the Trump administration missed its deadline to release millions of files and then released them in a way that exposed the victims while protecting the perpetrators.

While some European leaders, such as the former Prince Andrew, are facing harsh consequences for associating with Epstein, no Americans outside of Epstein and his closest associate Ghislaine Maxwell have faced any consequences, legal or otherwise.

That’s despite very concrete ties between the Trump administration and the sex trafficker. Not only did Trump’s Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick admit to visiting Epstein island after lying about it (and has so far faced no consequences), but Trump himself is named more than a million times in the files, according to lawmakers with access to the unredacted documents. Several victims identify Trump by name, alleging he raped and assaulted them.

And it’s not just Trump. Epstein was an equal opportunity fixer. He was just as friendly with liberals as he was with conservatives, including Summers, Clinton, and, disconcertingly for the American left, Noam Chomsky. For elites like Epstein, ideological differences were superficial. The real distinction was money, power, and connections.

Epstein was a glorified drug dealer and his drugs of choice were the vulnerable bodies of women and children, offered up to his friends and allies as the forbidden currency he traded in. A useful moniker has emerged to describe the global network of elites whose power and privilege continues to protect them from accountability: the Epstein Class.

Georgia Senator John Ossoff, who faces reelection in 2026, is deploying this label, understanding that voters — at least those who haven’t bought into the MAGA cult — are increasingly aware of the double standards that wealthy power players are held to.

“This is the Epstein class, ruling our country,” said Ossoff in reference to those who make up the Trump administration. “They are the elites they pretend to hate.”

He’s right. And if the Trump administration won’t hold them to account, Americans should demand leaders who will.

Sonali Kolhatkar is host and executive producer of Rising Up With Sonali, an independent, subscriber-based syndicated TV and radio show.

‘How meaning is built’

“Blackened Wood’’ (detail), by Erica Wessmann, in her show “Someone’s Home,’’ at Kingston Gallery, Boston, April 2-26.

The gallery says the show “approaches space as an active, unstable field. Their installations weave together research, constructed forms, and coded material histories to create environments that suspend fixed perspective. Often immersive and physically commanding, the work invites viewers to reconsider how meaning is built, disrupted, and shared within social and spatial systems.’’

‘Pinched little joykillers’

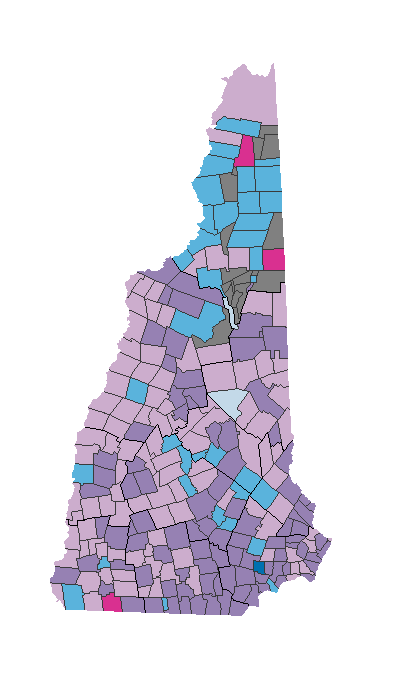

Largest reported ancestry groups in New Hampshire by town as of 2013. Dark purple indicates Irish, light purple English, pink French, turquoise French Canadian, dark blue Italian, and light blue German. Gray indicates townships with no reported data.

“New Hampshire has always been cheap, mean, rural, small-minded, and reactionary. It's one of the few states in the nation with neither a sales tax nor an income tax. Social services are totally inadequate there, it ranks at the bottom in state aid to education--the state is literally shaped like a dunce cap--and its medical assistance program is virtually nonexistent. Expecting aid for the poor there is like looking for an egg under a basilisk.... The state encourages skinflints, cheapskates, shutwallets, and pinched little joykillers who move there as a tax refuge to save money.’’

— Alexander Theroux (born 1939), Massachusetts-based novelist and poet

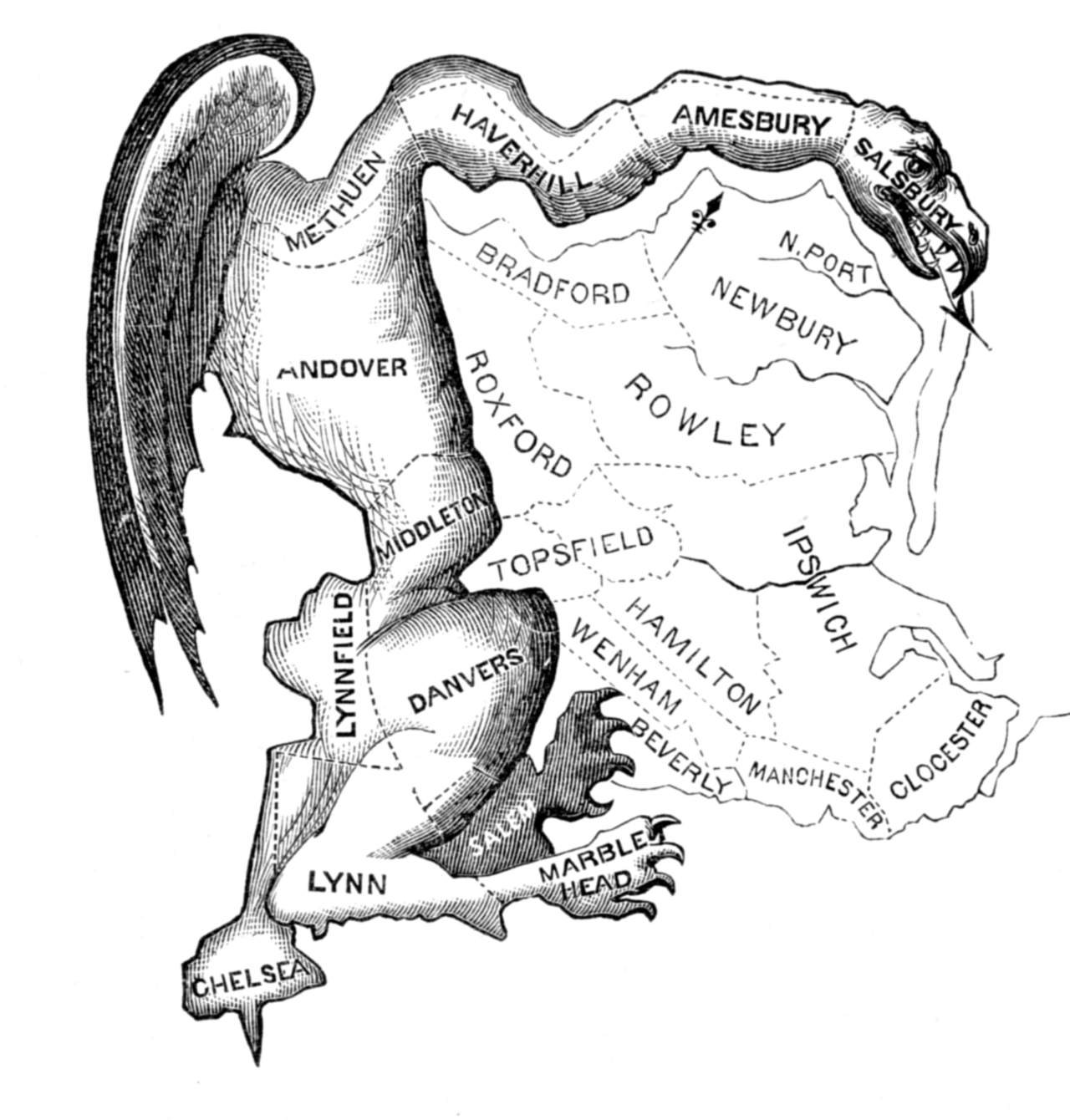

The birth of the Beast

Printed in March 1812, this political cartoon was made in reaction to the newly drawn state senate election district of South Essex created by the Massachusetts legislature to favor the Democratic-Republican Party. The caricature satirizes the bizarre shape of the district as a dragon-like monster, and Federalist newspaper editors and others at the time likened it to a salamander. But it came to be called the Gerrymander, after then-Gov. Elbridge Gerry, who supported the weird redistricting.

Llewellyn King: Big tech has become a ruthless autocratic oligopoly

Standard Oil's monopoly at the turn of the 20th Century was often depicted as an octopus, its tentacles infiltrating all aspects of American life. Vanderbilt Law Prof. Rebecca Allensworth says Big Tech companies are like octopuses — "every tentacle is a new set of products."

— Wikimedia Commons

Mark Zuckerberg, in 2005, as another rich kid at Harvard. See the movie The Social Network.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

"Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely.’’

—Lord Acton (1834-1902), English Liberal Party politician, and writer.

For me the most remarkable thing about Facebook boss Mark Zuckerberg’s appearance at a Los Angeles court, to answer questions about the addictive aspects of social media, was that he was there at 8:30 a.m. wearing a suit.

Sarah Wynn-Williams, in her excellent book about Facebook, Careless People: A Cautionary Tale of Power, Greed and Lost Idealism, said Zuckerberg doesn’t see anyone before noon because he has to sleep, having been up most of the night.

This had Wynn-Williams, who rose to head Facebook’s international relations team, sometimes telling heads of state that they would have to wait for the great man to alight from his bed at noon or later.

Zuckerberg could be uninterested or uninformed about the country from which he was trying to get favors for Facebook, she wrote. As Facebook had electorates in its thrall, countries’ leaders were prepared to defer to the sleeping titan.

This doesn’t mean that Zuckerberg is evil, but it does point to enormous self-regard. His sleeping routine is a de facto declaration: I am so rich and so powerful that I can command world leaders to rearrange their schedules to accommodate mine. They did, according to Wynn-Williams.

While the venerable observation by Lord Acton in 1887 is nearly always directed at politicians and autocrats, it is as true for billionaires and their companies.

More so with the tech gargantuans that are a force in the financial markets, a force in politics, and will control much of the future if their investments in artificial intelligence pay off. Among them are Meta (Facebook), Alphabet (Google), Amazon, Apple, Nvidia, Microsoft, Tesla, Anthropic and OpenAI.

Another point, which Wynn-Williams made in her book, is that most of the heads of state whom Zuckerberg treated with minimal respect won’t be in power in 10 years, but Zuckerberg, who is 41, may be around for half a century. The long game is his, along with his colleague-companies and their CEOs, especially when they own a commanding amount of the stock, such as Tesla’s Elon Musk.

The impact of Big Tech as a lobbying force is apparent: Any CEO has access to the White House and is in turn cultivated by the White House. Congress has a permanent welcome mat out to Big Tech lobbyists – and their campaign contributions.

A more damaging impact might be what Big Tech does to new tech.

The biggies buy up every startup that looks as though it might become a mega company. All of the Big Tech companies are conglomerates, and history has shown that conglomerates discard unprofitable enterprises and favor the cash cows. Tech autocracy is no kinder than any other autocracy.

Startups are what keep America ahead of the world in tech, and they are keenly watched for any sign that they may grow into another agent of change. Whereas at the beginning of the tech boom successful startups headed for an initial public offering, now they calculate from the get-go which behemoth tech company will buy them. The circle is closed.

The big get bigger and the startup is absorbed into a giant organization, where it might prosper or whither. Either way it is out of reach, including regulatory reach. It is in the castle walls.

As we see with the fate of CBS and The Washington Post, Big Tech can play havoc with the media and our right to know what is going on. The money is so large that it is almost impossible for politicians not to seek the favor of the mighty techs and their Vesuvian cash flow.

The obverse of that is what they might do if they overreach, as they may be doing now with AI investments, and bring down the stock market.

Big Tech has showered us with wonders that can make life easier and fun for many, but there is a price. The price is that we have handed the future to a group of companies that, understandably, are interested in self-preservation first, as with all autocracy.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS and an international energy-sector consultant. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island.

Ready to return home?

“Bubble Gum, Camp Pinecliffe, Maine (1981),’’ by Gay Block, in the group show “Welcome Home,’’ at the Addison Gallery of American Art, at Phillips Academy, Andover, Mass., March 3-July 31,

The gallery says about the show:

“What is home? How does it shape you? How do you shape it? Artists have long explored these difficult questions, capturing the idea of home and belonging in ways both tangible and abstract. Visitors are invited to ponder their own ideas of home in this exhibition curated by Phillips Academy students enrolled in ‘Art 400 Visual Culture: Curating the Addison Collection.’’’

Fidelity diving into crypto

Edited from a New England Council report

Fidelity Investments will soon launch the Fidelity Digital Dollar (FIDD), marking a significant expansion into the stablecoin market. The Boston-based financial-services giant will issue the digital currency through Fidelity Digital Assets, National Association, a national trust bank that received conditional approval from the U.S. Office of the Comptroller of the Currency in December.

FIDD will be pegged one-to-one to the U.S. dollar and backed by reserves held in short-term Treasury securities and cash, managed by Fidelity Management & Research Company LLC. The stablecoin will be available to both retail and institutional investors through Fidelity’s digital asset platforms and on crypto exchanges.

“We believe stablecoins have the potential to serve as foundational payment and settlement instruments,” Mike O’Reilly, president of Fidelity Digital Assets, told Bloomberg. “Real-time settlement, 24/7, low-cost treasury management are all meaningful benefits that stablecoins can bring to both our retail and our institutional clients.”

Make it stand out

Ready for anything

“Crown Maker” (oil on canvas), by Taha Clayton, in his show “Historic Presence,’’ at the Hotchkiss School’s Tremaine Gallery, Lakeville, Conn., through April 5.

The gallery says:

The show “features Brooklyn-based artist Taha Clayton’s portraits inspired by the 1930s to 50s, honoring the resilience, joy, culture, and dignity of elders. The exhibition includes works in oil, charcoal and graphite, enhanced with props from the artist’s creative process. Through these intimate and powerful depictions, Clayton invites viewers to reflect on legacy, identity, and the enduring beauty found in everyday life.’’

‘Hopeful offering to a world in pain’

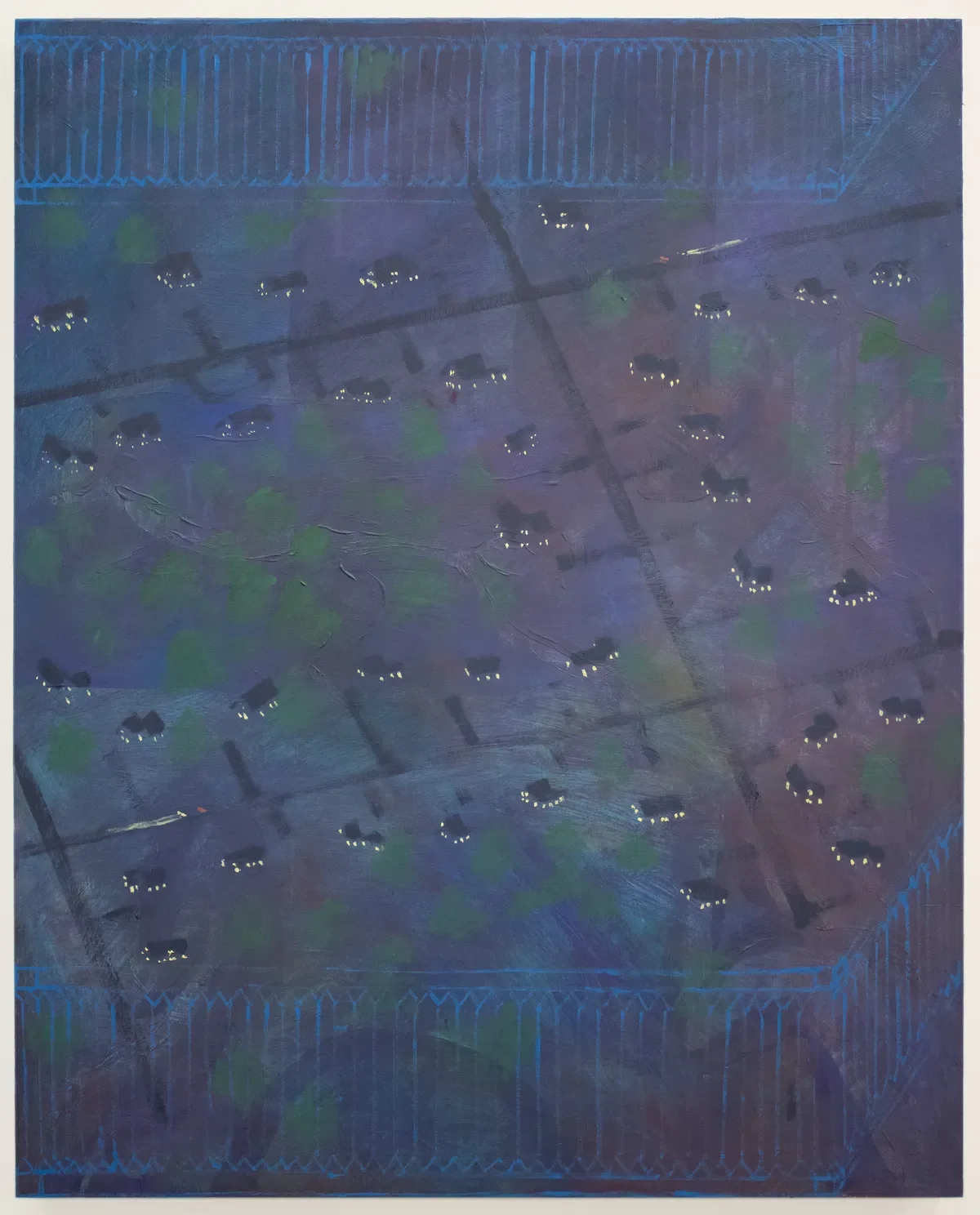

“Purple Neighborhood Decoration’’ (oil on panel), by Nick Benfey, in his show “Neighborhood,’’ at Moss Galleries, Falmouth, Maine, through April 11.

The artist says:

“Before I could drive a car, when I was about 13 or 14, I’d often walk from my friend’s house across our small town back to mine. Instead of going inside, I’d walk behind our house and stand by the garage. About 8 p.m., the sky deep blue or black depending on the season, my parents would be inside, maybe with friends over, talking. I’d stand there in the dirt next to the garage for a while, looking at the orange windows, breathing and not talking, a feeling of peace overtaking me. It was my secret that I’d do this, every time I walked home at night.

“Eventually I’d go inside and things would resume, the feeling wouldn’t last, I’d have to talk, I’d feel insecure and embarrassed again.

“That feeling is tied to these paintings, and I’m still unsure how to think about it, how to write about it, without feeling in some way guilty about relishing those memories of happiness. I hear another voice, With all the suffering in the world, you’re thinking about these trivial nostalgic… etc. It’s true, these are not paintings of the world’s sufferings. These are about joy, and peace, and quiet beauty, my inner world at the best moments of my life, a hopeful offering for a world in pain."

–Nick Benfey

Chris Powell: Teachers unions ready to take over Connecticut

“Dutch schoolmaster and children” (1662), by Adriaen van Ostade.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

For many years Connecticut's teacher unions ran a discreet political racket. Many of their members would hold teaching jobs in towns adjacent to the towns in which they lived and then seek municipal office in their home towns, particularly office on their local board of education. They were usually elected.

This arrangement -- working in one town, getting elected in another -- would mask a potential conflict of interest, wherein, as municipal officials, these board members would decide on or even negotiate contracts with a local affiliate of the statewide union to which they also belonged via their job in a neighboring town. Were board members most loyal to the public interest or to their union interest?

Since the connection of school board members to the union whose members get most money spent by school boards was seldom reported by news organizations, the question of primary loyalty was not posed in public forums. If it had been posed, it might have elicited a claim that the public interest and the union interest were identical. That might have been an interesting discussion.

The teacher unions racket is no longer discreet. For the Yankee Institute's Meghan Portfolio reported the other day that the state's largest teacher union, the Connecticut Education Association, now celebrates the racket. The union's December newsletter proclaims that in November's municipal elections 57 CEA members won elections in more than 45 towns, with only five of the union's candidates losing.

The CEA newsletter, Portfolio writes, “makes clear this was no spontaneous wave of civic participation. Candidates were guided through a union-run pipeline, including a formal questionnaire process and participation in the National Education Association's ‘See Educators Run' program."

The union threw its resources into its members' campaigns with e-mails, text messages, flyers, telephone calls, and door-to-door canvassing. Since name recognition and personal contact are the main deciders of most municipal elections, such electioneering is usually successful, especially since news coverage of school board elections, always skimpy, has vanished.

Indeed, the CEA may already have figured out that with just a little more effort it can gain control of every school board and town council in the state before people realize what is going on, there being no one left to tell them.

Of course this is only democratic politics in the era of local journalism's demise. Even people with the worst potential conflicts of interest have the right to run for public office, and special interests with access to big money, especially money derived from government, heavily influence if not control all sorts of political nominations and elections everywhere, though this is most pronounced with teacher unions’ power in the Democratic Party. Teacher union members typically constitute 10 percent of the party's national convention delegates.

But the special-interest influence in politics and government may be worst with teacher unions, since education is the prerequisite of democracy. Destroy education and you destroy democracy, and the trends in American education are terrible. Enrollments, student proficiency, and accountability are falling even as school costs keep rising, and civic engagement is collapsing along with journalism and literacy generally.

This is the perfect environment for special-interest control of government. No wonder the CEA, special interest No. 1, is celebrating.

College-student-loan debt remains a huge problem, so people may have welcomed the announcement last week that Connecticut's Student Loan Reimbursement Program has begun accepting applications for reimbursement of college student loan payments made in 2025.

Reimbursement of up to $5,000 per year is available to Connecticut residents who earned a degree in the state and are making $125,000 a year or less.

This isn't fair. It's really a bailout for the failure of higher education, which is grossly overpriced, long having awarded degrees of little use in making a living and having stuck its victims with debt that seriously impairs their lives or that, as with Connecticut's reimbursement program, is transferred to taxpayers, many of whom did not attend college or paid their own way.

It's another part of the education racket.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).