David Warsh: Keynes and Freud

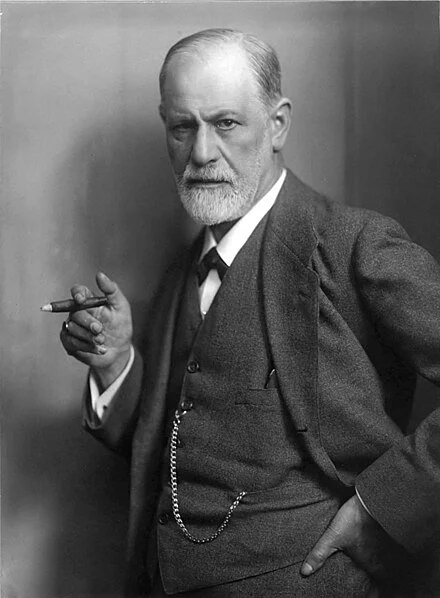

Sigmund Freud in 1921. His cigar addiction gave him oral cancer, which led to his death in London in 1939. He had fled there to escape the Nazis, after Hitler’s Germany had taken over Freud’s native Austria.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

This column has become interested in the difference of opinion between John Maynard Keynes and Milton Friedman with respect to their explanations for the causes of the Great Depression, Keynes blamed social aggregates within the economy itself for a sudden fall, Friedman blamed an inept Federal Reserve. History has shown that Friedman was right and Keynes wrong.

Last week I likened both men to Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, a split personality from the famous novel by Robert Louis Stevenson. The comparison seemed apt for Friedman, insofar as in contrast to the relative precision of his theorizing, the policies he recommended as a cultural entrepreneur, especially in Capitalism and Freedom, routinely departed from those I consider sensible. Alec Cairncross put the case for economic realism well in an address on the two hundredth anniversary of Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations:

“We are more conscious perhaps than Adam Smith of the need to see the market within a social framework and of the ways in which the state can usefully rig the market without destroying its thrust. We are certainly far more willing to concede a larger role for state activities of all kinds, But it is a nice question whether this is because we can lay claim, after two centuries, to a deeper insight in determining the forces determining the wealth of nations or whether more obvious forces have played the largest part: the spread of democratic ideals, increasing affluence, the growth of knowledge, and a centralizing technology that delivers us over to the bureaucrats.”

The Jekyll/Hyde comparison seemed to work relatively well in Friedman’s case. Abolish Social Security? Stop licensing the professions beginning with physicians? Get rid of national health insurance? Hog-tie the Fed in crises? “Starve the beast” of government by cutting taxes to the bone? Come on, Mr. Hyde!

The comparison did not, however, suit Keynes . Even the excesses of “The End of Laissez Faire” stopped short of murdering his darlings. The challenge was to come up with a metaphor for Keynes that seemed to work.

Let’s try Sigmund Freud on for size.

Both men were born in the 19th Century, Freud in 1869, Keynes in 1883. Both came of age in a time of great excitement about the possibilities of new sciences. The Interpretation of Dreams appeared in 1905 and The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money in 1936.

Both men wrote extremely well, both sought to overturn substantial portions of the received wisdom of their respective fields, Keynes with an intuitive vision of macroeconomics (a term late supplied by Ragnar Frisch), Freud with psychoanalysis. Both depended on influential discussion groups to advance their views. Both achieved enormous influence on culture in their day. Both inspired celebrated biographies.

The economist was well acquainted with Freud’s work. Keynes told a friend he was reading through all Freud’s books. He wrote a letter to a magazine calling the psychoanalyst “one of the great, disturbing geniuses of our time.” I found no evidence that Freud read Keynes, but he didn’t look very far. Freud died in 1939, Keynes in 1946. Subsequent critics, mostly from the analytic community, have argued that Keynes’s view of human nature was very similar to that of Freud.

But the real similarity between the two scientists/latter-day culture entrepreneurs has to do with the posthumous influence of their work. Freud’s reputation as a successful scientific revolutionary and culture entrepreneur has been steadily diminished by advances in other branches of psychology, neurology and diagnostics.

Within technical economics. Keynes’s authority began to ebb in the ‘70’s Clarified an refined by generations of system builders, incorporated in formal models, “neo-Keynesian” views remain widespread. But macroeconomics is in flux today, and there is no way of telling how, in 20 or 30 years, Keynes’a contribution will be viewed.

This much seems likely: because he wrote so well, Keynes’s reputation in the humanities, like that of Freud, will prove to be imperishable.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay originated.