Philip K. Howard: Paralyzing ‘rights’ are used against the public interest; bring back fair accountability

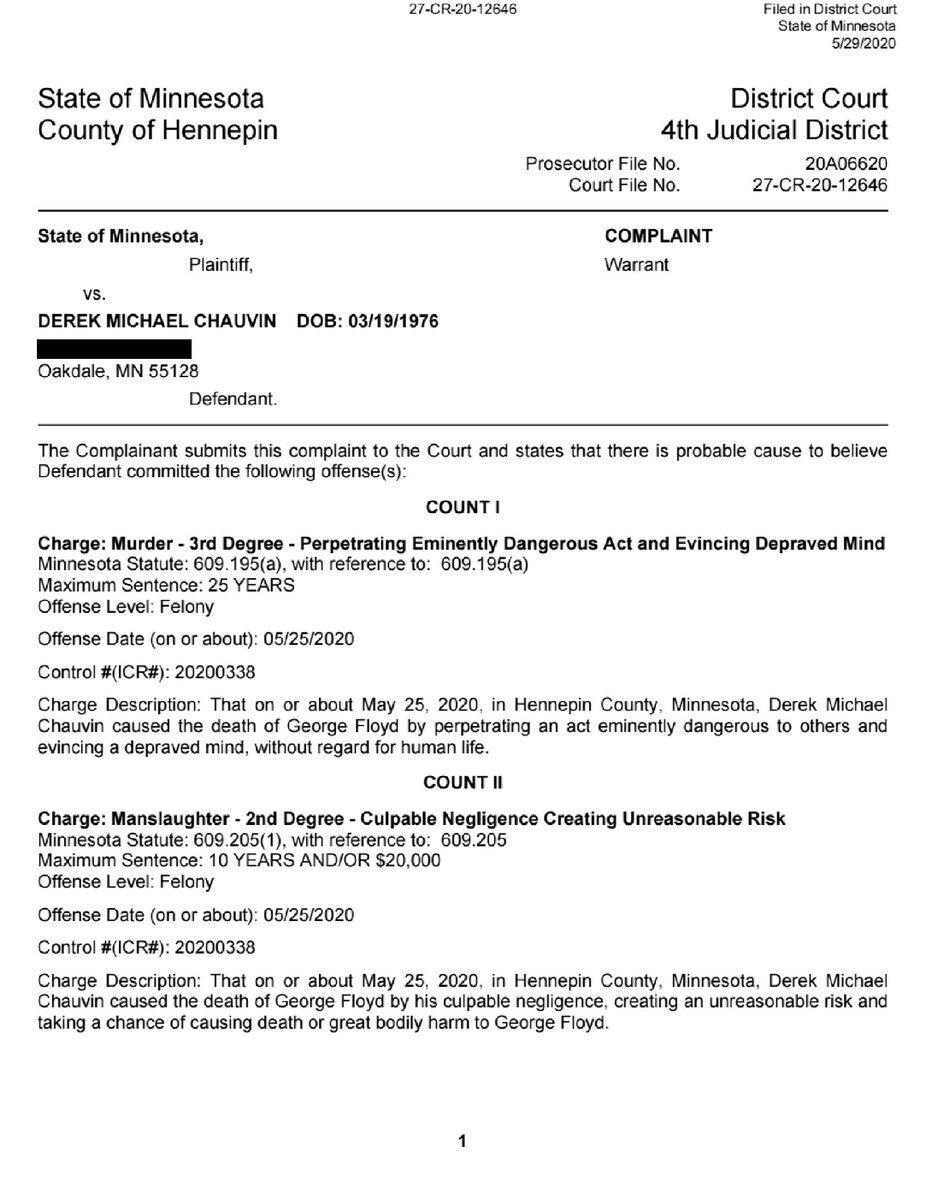

The conviction of Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin for killing George Floyd may elevate trust in American justice, but it will do little, by itself, to repair trust in police. Nor can political leaders and their appointees do much to restore that trust, because police “rights” still render officers virtually immune from accountability and basic management decisions. Chauvin was known to be “tightly wound,” and the police department had previously received 18 complaints about him abusing his power. Despite the complaints, he was not terminated or transferred. He had his rights.

But what about the public’s rights against abusive officers? We should be protected from bad cops, of course, but we can’t get there using the language of rights. Analyzing public accountability as a matter of rights is circular: Whose rights?

Rights rhetoric sprung out of the 1960s to defend freedom against institutional discrimination. But rights have evolved into an offensive weapon against the legitimate interests of other citizens—by police to avoid accountability, by teachers to avoid returning to work, by journalists and academics to cancel offensive speech.

The fabric of a free society is torn by these self-interested rights. Upholding values like fairness, reciprocity, and mutual respect is difficult when individual rights preempt the rights of everyone else.

The solution is simple: Hold people accountable again. Take “tightly wound” cops off the beat. If college students cancel other students’ freedom to hear a speaker, invite the cancelers to matriculate elsewhere. Healthy teachers who claim their potential covid exposure entitles them not to teach should find other jobs: Why should they be more privileged than nurses and grocery clerks?

But there’s a hitch: Holding people accountable is claimed to violate their rights. We seek more justice, fairness, and freedom, but we deny ourselves the tool of accountability needed to accomplish these goals.

It’s time to reset the balance between public accountability and concerns about individual fairness. Accountability must be taken out of the penalty box: Restore the freedom, up and down the chain of responsibility, to make judgments about other people and their actions. We can provide safeguards against unfairness, but law should intercede only where there is systemic discrimination or demonstrated harassment.

A Condition of Freedom

Every day, each of us evaluates the people we deal with. These judgments about other people influence how we associate, come together, and strive to achieve our private and societal goals.

People judging people is the currency of a free society.

We think of accountability in its negative sense—as the stick for inadequate performance. But accountability is needed for a positive reason—to instill the mutual trust that everyone is doing their share. It assures mutuality of effort and values. Coworkers need to believe that energy, virtue, and cooperation will be rewarded while mediocrity, indifference, and selfishness will not be tolerated.

The paradox of accountability is that once it’s available, it rarely needs to be exercised. What’s important is the availability of accountability. Once mutual trust and obligation are established, an energetic and cooperative culture leads people to do their best.

Accountability is also the organizing principle of democracy: voters elect leaders who preside over an unbroken chain of accountability down to subordinate officials. But the links in our chain of accountability are broken. Police chiefs, school principals, and government commissioners have lost their ability to hold their personnel accountable. Over 99 percent of today’s federal employees receive a “fully successful” job rating. California has one of the country’s worst school systems but can terminate no more than two or three teachers per year for poor performance. In New York, a teacher who went to jail for selling cocaine had to be reinstated in his job after his release. Under Minneapolis’ collective bargaining agreement with its union, the city’s police chief couldn’t even reassign Derek Chauvin for past misconduct, let alone terminate him, without a legal proceeding.

Democracy can’t function effectively without accountability. The conditions for social trust disappear. One effect is widespread anger and resentment at people acting irresponsibly or demanding things they don’t deserve. Society goes into a downward spiral of cynicism and selfishness. Sometimes people take to the streets.

The Illusion of Objectivity

Most people probably support the idea of accountability; but who decides, and on what basis? Most experts and academics think the job can be defined by metrics, “key performance indicators,” or other unimpeachable criteria. The Supreme Court has embraced this idea: Thus, one dubious innovation of the 1960s rights revolution was the application of due process to public personnel decisions. “It is not burdensome to give reasons,” Justice Thurgood Marshall stated, “when reasons exist.”

But “objective” accountability leads inexorably to no accountability. Being a good cop, teacher, or coworker is more complex than can be defined by objective criteria. Focusing too much on metrics—test scores, arrests, quarterly profits—will skew behavior in ways that are typically destructive. As Jerry Muller puts it in The Tyranny of Metrics (2018), measurement is useful as a tool of human judgment but not a replacement for it.

Thus, the No Child Left Behind law held schools accountable for increases in test scores—and turned many schools into drill sheds. Some school officials, supposedly role models for our youth, were caught in organized cheating schemes. In a similar way, judging surgeons by their mortality rates led many to avoid the difficult surgeries that require the most skill. Paying corporate employees according to short-term sales or profits means they will act in ways that undermine long-term corporate health.

Successful accountability rarely involves black-and-white choices. The most important qualities of employees can’t be captured by objective criteria. Good judgment, a can-do attitude and a willingness to help others can be readily identified by co-workers but are not objectifiable.

A KIPP charter school principal described to me a teacher who looked perfect on paper and tried hard but could not succeed:

He just couldn’t relate to the students. It’s hard to put my finger on exactly why. He would blow a little hot and cold, letting one student get away with talking in class and then coming down hard on someone else who did the same thing … but the effect was that the kids started arguing back. It affected the whole school. Kids would come out of his class in a belligerent mood.… We worked with him on classroom management the summer after his first year. It usually helps, but he just didn’t have the knack. So, we had to let him go.

In The Moral Life of Schools (1993), a landmark study of the traits that distinguish effective teachers, Philip Jackson and his colleagues concluded,

Laying aside all exceptions, … there is typically a lot of truth in the judgments we make of others. And this is so even when we cannot quite put our finger on the source of our opinion. That truth, we would suggest, emerges expressively. It is given off by what a person says and does, the way a smile gives off an aura of friendliness or tears a spirit of sadness.

To complicate accountability judgments, they involve not just particular persons but the way they perform in particular settings. An effective grade-school teacher may be ineffective teaching high school. “Men are neither good nor bad,” as management expert Chester Barnard observed, “but only good or bad in this or that position.”

Today, the most important criteria for fair accountability are irrelevant because they’re not objectively provable. Some of the qualities “considered too subjective to stand up in court,” as Walter Olson notes in The Excuse Factory, include these: “temperament, habits, demeanor, bearing, manner, maturity, drive, leadership ability, personal appearance, stability, cooperativeness, dependability, adaptability, industry, work habits, attitude toward detail, and interest in the job.” How could the Minneapolis police chief prove that Derek Chauvin was too tightly wound?

The Irreducibility of Human Judgment

Reviving accountability requires coming to grips with the reality that it always requires subjective judgments, in context, about the relative performance of each employee. Since the 1960s, America has rebuilt its governing structures to eliminate human judgment as far as possible. Letting people make judgments about others leaves room for unfairness or bias. Who are you to judge? Worse, we’re told to distrust our own judgments as vulnerable to unconscious bias. How can we protect against that?

What’s needed is a new protocol that instills some level of trust in accountability judgments without getting mired in rigid rights, metrics, and near-endless legal arguments. The obvious solution is to restore the legitimacy of human judgment not only for supervisors but also for other stakeholders. Studies suggest that coworkers usually have a consensus view on who’s good and who’s not: “Everyone knows who the bad teacher is.”

A school could have a parent-teacher committee with authority to veto unfair termination decisions. A police department could have an accountability review committee comprised of police, prosecutors, and citizen representatives. Private companies like Toyota have workers’ councils that give opinions before an employee is let go.

Oversight committees are hardly infallible but can provide speed bumps against supervisory unfairness. Discriminatory practices can still be reviewed by courts or other authorities where there are credible allegations of systemic discrimination.

But the pervasive overhang of legal threats for personnel judgments must be removed. Legal proceedings asserting individual rights against accountability will be irresistible to many affected workers. Nature has wired people to self-justify, and the accountable individual, studies show, is uniquely incapable of judging the fairness of such a decision. How well anyone does in an organization, Friedrich Hayek put it, “must be determined by the opinion of other people.”

We’re trained to be reluctant to let people judge other people; we want legal proof. But putting personnel judgments through the legal grinder is even less reliable. How do you prove which person doesn’t try hard, or which teacher can’t hold students’ attention?

Journalist Steven Brill described one 45-day hearing to try to terminate a teacher who was not only inept but didn’t try. She never corrected student work, filled out report cards, or met even the most rudimentary responsibilities. Her defense? There was no proof that she had been given an instruction manual telling her to do these things. This type of sophistry is typical in due process hearings: As one union official put it, “I’m here to defend even the worst people.”

Cooking accountability in a legal cauldron is in most circumstances a recipe for bitterness and frustration. The personal disappointment of a job not working out, which would be quickly forgotten if the person got a new job, becomes a kind of holy war, consuming the life of the individual supposedly protected. Discrimination lawsuits are notorious for both their high emotions and their low success rate. A federal judge told me about a case in which the evidence was overwhelming that the employee was not up to the job—but the worker was in tears at the injustice done to him.

Honoring Everyone Else’s Rights

No human grouping can long survive if its members flout accepted norms of right and wrong or tolerate failure as normal.

The quest to make accountability a matter of objective proof has turned out to be a blind alley, leading inexorably to unaccountability. No one should have the right to be unaccountable. Any claim of superior rights violates everyone else’s rights. Rights are supposed to protect against unlawful coercion, not against the judgments of other free citizens or the choices needed to manage an institution.

Putting the magnifying glass on the accountable individual ignores the rights of other affected individuals. What about the unfairness to coworkers and the public of having to deal with an uncooperative or inept person? For institutions, removing accountability is like pouring acid over workplace culture. The 2003 Volcker Commission on the federal civil service found deep resentment at “the protections provided to those poor performers” who “impede their own work and drag down the reputation of all government workers.” That’s why America’s public culture too often lacks energy, pride, and effectiveness.

Democracy fails when public institutions can’t do their jobs properly. As demonstrated by abusive cops and inept teachers, viewing accountability as a matter of individual rights means that police, schools, and other social institutions can’t serve the public effectively. Democracy becomes vestigial, a process of electing figureheads who have little effective authority over the way government operates.

In all these ways and more, the loss of accountability has eroded the rights and freedoms of all Americans, compromising much of what is admirable and strong in American culture. Good government is impossible unless officials have room to use their common sense, but no one will trust officials without clear lines of accountability.

Like putting a plug back in a socket, restoring accountability will reenergize human initiative in government and throughout society. Most people want the freedom and self-respect of doing things in their own ways and the camaraderie of working with others who also value human initiative. But the freedom to take initiative has one condition: accountability. Individuals cannot be immune from the judgments of others without undermining freedom itself.

Philip K. Howard, a New York-based civic leader, author, lawyer and photographer, is founder of Common Good (commongood.org) and author, most recently, of Try Common Sense: Replacing the Failed Ideologies of Right and Left (2019). This essay first appeared in American Purpose