Sensing a winning issue, Connecticut Gov. Dannel Malloy used his last debate with his Republican rival Tom Foley to lecture Foley about the name of his yacht, Odalisque, a name derived from the Turkish word for concubine, though it has evolved to include portraiture of the naked female form.

"You have a daughter," Malloy harrumphed at Foley. "Do you really think it's appropriate to have a boat named after a sex slave?"

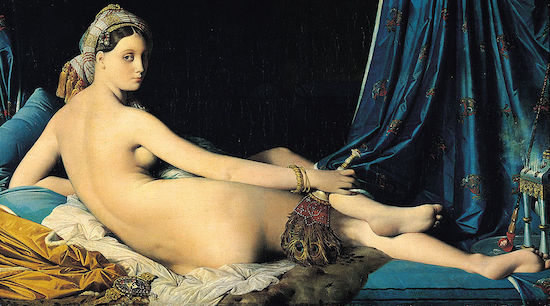

Foley, a very rich businessman, insisted that his aim in naming the yacht had been to evoke art, not lust, and he cited the works of the French painters Matisse and Ingres. At last the campaign had come upon a subject about which Foley knew something -- just not one involving public policy or likely to make him seem like a man of the people.

But if Foley had known less about art and more about Connecticut he might have turned the tables on the governor, whom of course, won the election. For in one respect sex slavery is actually state government policy, fervently supported by the Democratic Party's most fearsome ideologues.

It happens when abortions result from the sex slavery of minors.

This rationalization of sex slavery was first noticed in 2007 when a West Hartford man was charged with harboring and using as a sex slave a 15-year-old girl who had run away from her home in Bloomfield. Having impregnated the girl, the man sent her to an abortion clinic, where the pregnancy was terminated with no serious questions about the girl's circumstances or about her parents or guardian, with the girl returning to her sex slavemaster. Those who remarked that the case argued for legislation to require parental notification for abortions on minors were denounced as Neanderthals.

A similar case became public in Coventry, Conn., last year with the arrest of the fire chief, who was having frequent sex with a cadet member of the department when she was 15 and impregnated her when she was 16. As a matter of law it was all rape, even at 16, since the girl, as a cadet, was under the chief's authority. The chief also arranged for the girl's abortion without anyone being the wiser. In this case Connecticut's lack of a parental -notification law concealed not only the sustained sexual exploitation of a minor but also an abuse of official power that itself had been specifically criminalized. But this time the horrible circumstances were taken for granted.

For in Connecticut a boat that might have been named after a sex slave is purported to be a political scandal, an affront to the dignity of women generally and children particularly, but sex slavery for children is considered preferable to requiring an inquiry into the rape of minors when abortions are to be performed on them.

* * *

The rhetoric of the recent election campaign in Connecticut was full of the cliche that government should be run more like a business. But that's exactly the problem -- that government in Connecticut already operates like a business, primarily to make money for itself in a monopoly environment rather than to uphold a social obligation and perform a public service.

Student test scores and the explosion in the need for remedial courses show that education has been declining even as its cost is always rising.

A half-century of poverty policy hasn't elevated the poor to self-sufficiency but instead has created and sustained a vicious cycle of dependence and degradation in which nearly half the state's children now grow up without fathers.

Criminal-justice policy serves mainly to give a third of the state's young black and Hispanic men criminal records that leave them unskilled and largely unemployable for most of their lives.

But education, poverty, and criminal justice are the major employment agencies of government, providing livelihoods with great salaries, benefits and pensions to tens of thousands of people regardless of the results of their businesses, results that are never audited but are infinitely more damaging than anything from which the infamous Koch Brothers make their money.

Chris Powell is managing editor of the Journal Inquirer, based in Manchester, Conn.