Climbing Moosilauke: Pride goeth before the fall

On the mountain: From left, college classmates Win Rockwell, Josh Fitzhugh, Chris Buschmann and Bob Harrington.

— Photo by Jane Andrews

Truth be told, I prefer paddling to hiking, and one thing I’ve learned from the former is that sometimes it’s good to go with the flow. So when two classmates from my Dartmouth College days invited me to join them at our 52th reunion (the big 50th, in 2020, was cancelled because of COVID) and hike up to the top of Moosilauke Mountain, in New Hampshire, I said sure, count me in.

I had another, nostalgic reason for going besides friendship and bravado. Thirty three years ago, when my father was 75, he hiked up and down Moosilauke with a little help from his two sons. Both my father and my older brother were also Dartmouth graduates. “If he could do it, so can I,” went the message in my mind. The fact that, at 74, I was a year younger compensated in my mind for the other fact: I have early-stage Parkinson’s disease. (Symptons of Parkinson’s include tremor and instability.)

Now Moosilauke, elevation 4,803 feet, is sometimes called Dartmouth’s Mountain,” partly because the college owns quite a bit of the land surrounding the peak, partly because it used to hold ski races down its flank in the 1920s and 1930s, and partly because it has a timbered lodge at its base that welcomes students, faculty, alumni and sometimes even celebrities alike into what for many is iconic about Dartmouth: its connection to the wilderness of northern New Hampshire. Recently, the lodge has been extensively rebuilt using massive timbers, and, of course, New Hampshire granite.

I met my classmates, Win Rockwell and Bob Harrington, and Bob’s partner, Jane Andrews, at a park-n-ride near my home in Vermont at 7 A.M. and we drove over to the base lodge, arriving at 9.

It was a warm June day, with the sky almost cloudless. I had grabbed a coffee and roll for breakfast on our way, and the lodge had packed us a bag lunch consisting of cheese, tomato, bread, peanut butter and jelly sandwichs and brownies. I had two 8-ounce water bottles. In my knapsack I carried warmer clothing for the top in case I needed it. (In my father’s climb, one obstacle was snow at the top. The temperature in the White Mountains can sometimes rapidly drop 50 degrees at the summits, with wind gusts of 40 miles an hour or more.) It was warm enough for shorts. I had climbing boots but very light socks, which were intended to give my toes more room. (I like the boots but sometimes my toes banged into the leather.) I suffer from peripheral neuropathy in both feet, but the tingling I usually experience had not previously bothered me walking.

After discussion amongst my friends, I also decided to take a pair of bamboo cross-county ski poles to assist in balance and motion if necessary. Many people now hike with poles, some extendable, regardless of age.

We left on the main trail from the lodge at 10 a.m. The straightest route to the summit (the route we took) is about 3.5 miles up the Gorge Brook trail, with an elevation climb of 2,933 feet. Hikers in good condition traveling in dry conditions should be able to make it to the peak and back in about 3 hours, with a 20-minute break at the summit.

As we started our hike, I tried to recall my last outing three and a half decades ago. The trail seemed a bit rockier this time and I didn’t recall hearing the water tumble over rocks in the nearby brook. At first all seemed fine. Gradually, however, I felt more and more as though I was walking in the brook, not because the going was wet but because I was having to step rock to rock rather than walk on soil or gravel. In places the soil had eroded so much that the college (through the Dartmouth Outing Club, I believe) had placed large flat stones in a kind of stairway, with the rises varying from 6 inches to a foot and a half.

We stopped after about a mile to eat some of our provisions and enjoy the view to the north. I felt fine if a bit tired. We were passed periodically by younger hikers, some alone and many with dogs. At about the two-mile mark I began to ask hikers coming down the time to the summit. “Oh, it’s not too far,” was a common response.

At about 2.5 miles in I started having balance issues. Now, though I have Parkinson’s, I had not had before one of the common symptoms, instability. Mostly I have a slight tremor in my right hand and some slurring of speech. I tend to walk slowly with a forward hunch. I’m a former soccer fullback, downhill skier and amateur logger, and I’m still in decent shape. But here on Moosilauke, I found myself losing my balance to the rear. In short, I kept falling backwards! My poles helped a bit, but sometimes I found myself having to take two steps back. Then, in one fall, I slammed my left temple hard into a rock in part of the trail that was mostly boulders.

Now you’ve done it, I said to myself, fearing a subdural hematoma, swelling, loss of consciousness and death. Luckily, my friends came to my rescue, checked my vision and saw no bleeding. I had no headache. We continued, but more slowly, with one classmate walking just behind me. I thought of the old Dartmouth song that refers to its graduates having the granite of New Hampshire “in our muscles and our brains.” It’s a good thing, I thought.

At about the two-mile point of the hike, there is a false summit. You are above the tree line and the view opens up. Solid granite outcroppings replace the big boulders we had been walking on. Thinking that we were close to the top, I exulted until, looking again, I saw another rise ahead. “Is that where we have to go?” I asked wearily. “’Fraid so,” said Win, whose father had hiked all over these mountains as a student at Dartmouth in the 30s. “I think I better turn back,” I responded to the general agreement of my team. It was about 2:30 p.m.

Bob agreed to monitor me down the trail, although that meant he lost his opportunity to reach the summit. The other two, Win and Jane, seemed very fresh and expressed their desire to push on and catch up to us on the way down.

Bob Harrington and Jane Andrews made it to the top.

Now most hikers learn quickly that “down” does not necessarily mean “easier.” While I need to lift 219 pounds (my weight) with each step going up, I need to stop the inertia force of 219 pounds going down. In addition, at least for me, on rocky terrain I fear falling downhill more than I fear falling uphill. Gravity will aggravate the momentum falling downhill, I reason.

For me and Bob, then, the trip to the lodge became slower and slower. My legs were weakening and I was becoming very careful about each step. The routine was the same: Get yourself steady, examine the terrain ahead, identify a landing spot, plant poles, transfer weight to the downhill foot in a kind of leap of faith, say a small prayer when you succeeded, repeat.

At about 4 p.m., Jane and Win caught up with us on their downhill journey. Bob and I were only about a mile into our descent. We were stopping every 100 yards or so to let me rest. The decision was made to send Bob and Jane back to the lodge for possible assistance while Win would try to assist me. (We were joined about then by another Dartmouth graduate and his wife, Rick and Lucie Bourdon, who altered their plans to help both physically and emotionally in what was increasingly becoming an ordeal for all of us.)

It’s worth noting here a word about Moosilauke. When the mountain was first developed, in the early 1900’s, a cabin was built at the peak for overnight lodging. (It burned to the ground in 1942.) To help construct and provision that cabin, a dirt road was constructed to the peak. With the destruction of the cabin, that road got less and less traffic and is now mostly overgrown. You can hike on that road, but it is not much easier than the other trails. You also need to be at the peak or the base lodge to access that “carriage road,” so we had no choice but to go down the way we had come up.

In short, once you climb up on Moosilauke, the only way down is to walk, or be carried. Despite my wish as expressed during the descent, there is no zip line or chair lift for exhausted duffers like me. I stopped and sat on rocks or tree stumps with increasing frequency. (“Josh you are doing fine,” Lucie would say. “You have a team behind you!”) At one point Win and I decided that it was better to bushwack off the trail than struggle rock by rock while on it. At least then when I fell the branches and moss- covered rocks I hit were softer than the rocks in the trail, and saplings sometimes provided handholds to brake my descent.

Thankfully, this was one of the longest days of the year and the weather was clear and mild. Nevertheless, by 7 p.m. it was getting dark and we were still a half mile from the lodge. There was still a steep rocky trail ahead. I stumbled off the trail near the brook that I had heard on the way up. Losing my balance I fell, and could not get up. The muscles in my legs were too tired. After Win (who is probably 60 pounds lighter than me) dragged me to a soft spot off the trail, I remember saying, “You guys will have to figure out what to do. I’m done.” I stretched out, closed my eyes and tried to sleep.

By this point, Lucie and Rick had gone on ahead to report my condition and check on help. It began to rain and Win loaned me a parka. It wasn’t expected to be a cold night, and so I said, “Just get me a tarp and my sleeping bag at the lodge. I’ll just spend the night here!” “No way,’’ said Win.

It was dark by the time that two Dartmouth students, Alex Wells ’22 and Jules Reed ’23, arrived. Both were working in the kitchen at the lodge, but had hiking experience, and they had head-mounted flashlights. After they lifted me by my shoulders, I slung one arm over each of their necks. Then, like some six-legged decrepit spider, or a drunken Rockettes threesome, we inched our day down the trail with each of us simultaneously deciding which rock to step upon. When either of them tired, Win took their place.

Forty minutes later we could see the lights from the lodge, and closer still, the lights from the cabin I was sleeping in. No dinner for me, I told them, just get me to my bunk and bring me a bottle of wine. They did and I collapsed in bed, thankful to have made it down and for the help that made that possible. The next morning I learned that Win had used the lodge’s one telephone (there is no cell service at Moosilauke) to call my wife and leave a message. “First of all, let me tell you that Josh is okay,” he had begun.

Postscript

Decades ago, while in high school, I would occasionally quote Socrates, the Greek philosopher, who had said, “the unexamined life is not worth living.” When I have encountered traumatic moments in my life, I have sought to learn from the experience. This was no different. What caused my collapse on the mountain? Should I ever hope to hike again? Could others learn from my ordeal?

Looking back, I clearly should have prepared more for this hike, by taking some shorter hikes with lesser elevations, by having boots that fit better, by using proper hiking poles rather than old, bamboo cross-country poles, and by having a better breakfast and more robust lunch. I should have taken more water and less cold-weather gear in my backpack.

Maybe with Parkinson’s I should not have gone at all. The stress of the climb certainly exacerbated my instability, and my condition put a big burden on my friends. For them, it turned what could have been a delightful summer hike into a memorable, anxious ordeal. Of course, it also reaffirmed the value of friends and the Dartmouth “family.” I would have stayed on that mountain were it not for my saviors.

I do think that the college shares some responsibility for the episode. While I did not inquire, there were no notices that I saw of trail conditions or warnings that the Gorge Brook trail might be unsuitable for people over the age of 70 or suffering from ambulatory instability. Stating the obvious perhaps would be a caution that climbing the mountain is not the hardest challenge; you still have to get down!

In the years since I last climbed Moosilauke, with my father and brother, the trail to the summit has deteriorated greatly from the flow of rain and melting snow. Rather than relocating the trail, the college has sought to remedy it by making a staircase in many locations This works for those with strong knees, hips and ankles but for those like me, hundreds of 12-inch risers exhaust quite a bit of energy both going up and coming down. A better solution to trail washout might be to deposit 1-or-2-inch crushed stone in the interstices between the larger boulders to create a kind of stone path to the summit. This would be difficult and expensive and certainly change the nature of the hike, but it also would improve accessibility and safety, in my humble opinion. If this is feasible I’d be happy to contribute. I have a debt to repay.

From left, Josh Fitzhugh and Good Samaritans Jules Reed and Alex Wells with me after my misadventure.

John H. (“Josh”) Fitzhugh is a writer, former insurance-company CEO, former newspaper editor and publisher and former legal counsel to two Vermont governors. He lives in Vermont, Florida and on Cape Cod.

Harris Meyer: Amidst intense controversy, FDA approves Biogen’s Alzheimer's drug

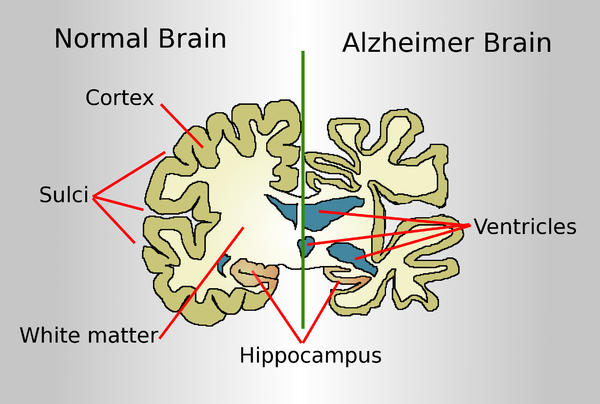

Drawing comparing a normal aged brain (left) and the brain of a person with Alzheimer's (right). Characteristics that separate the two are pointed out.

The Food and Drug Administration has approved the first treatment for Alzheimer’s disease, a drug developed by Biogen, which is based in Cambridge’s Kendall Square neighborhood. But the approval highlights a deep division over the drug’s benefits as well as criticism about the integrity of the FDA approval process.

The approval of aducanumab came despite a near-unanimous rejection of the product by an FDA advisory committee of outside experts in November. Doubts were raised when, in 2019, Biogen halted two large clinical trials of the drug after determining it wouldn’t reach its targets for efficacy. But the drugmaker later revised that assessment, stating that one trial showed that the drug reduced the decline in patients’ cognitive and functional ability by 22 percent.

Some FDA scientists in November joined with the company to present a document praising the intravenous drug. But other FDA officials and many outside experts say the evidence for the drug is shaky at best and that another large clinical trial is needed. A consumer advocacy group has called for a federal investigation into the FDA’s handling of the approval process for the product.

A lot is riding on the drug for Biogen. It is projected to carry a $50,000-a-year price tag and would be worth billions of dollars in revenue to the Cambridge company.

The FDA is under pressure because an estimated 6 million Americans are diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, a debilitating and ultimately fatal form of dementia, and there are no drugs on the market to treat the underlying disease. Although some drugs slightly mitigate symptoms, patients and their families are desperate for a medication that even modestly slows its progression.

Aducanumab helps the body produce antibodies that remove amyloid plaques from the brain, which has been associated with Alzheimer’s. It’s designed for patients with mild-to-moderate cognitive decline from Alzheimer’s, of which there are an estimated 2 million Americans. But it’s not clear whether eliminating the plaque improves brain function in Alzheimer’s patients. So far, nearly two dozen drugs based on the so-called amyloid hypothesis have failed in clinical trials.

Besides questions about whether the drug works, there also are safety issues. More than one-third of patients in one of the trials experienced brain swelling and nearly 20 percenty had brain bleeding, though those symptoms generally were mild and controllable. Because of those risks, patients receiving aducanumab have to undergo regular brain monitoring through expensive PET scans and MRI tests.

Some physicians who treat Alzheimer’s patients say they won’t prescribe the drug even if it’s approved.

“There’s a lot of hope among my patients that this is going to be a game changer,” said Dr. Matthew Schrag, an assistant professor of neurology at Vanderbilt University. “But the cognitive benefits of this drug are quite small, we don’t know the long-term safety risks, and there will be a lot of practical issues in deploying this therapy. We have to wait until we’re certain we’re doing the right thing for patients.”

Many aspects of aducanumab’s journey through the FDA approval process have been unusual. It’s “vanishingly rare” for a drug to continue on toward approval after its clinical trial was halted because unfavorable results showed that further testing was futile, said Dr. Peter Lurie, president of the Center for Science in the Public Interest and a former FDA associate commissioner. And it’s “mind-boggling,” he added, for the FDA to collaborate with a drugmaker in presenting a joint briefing document to an FDA advisory committee.

“A joint briefing document strikes me as completely inappropriate and an abdication of the FDA’s claim to being the best regulatory agency in the world,” Lurie said.

Three FDA advisory committee members who voted in November against approving the drug wrote in a recent JAMA commentary that the FDA’s “unusual degree of collaboration” with Biogen led to criticism that it “potentially compromised the FDA’s objectivity.” They cast doubt on both the drug’s safety and the revised efficacy data.

The FDA and Biogen declined to comment for this article.

Despite the uncertainties, the Alzheimer’s Association, the nation’s largest Alzheimer’s patient advocacy group, has pushed hard for FDA approval of aducanumab, mounting a major print and online ad campaign last month. The “More Time” campaign featured personal stories from patients and family members. In one ad, actor Samuel L. Jackson posted on Twitter, “If a drug could slow Alzheimer’s, giving me more time with my mom, I would have read to her more.”

But the association has drawn criticism for having its representatives testify before the FDA in support of the drug without disclosing that it received $525,000 in contributions last year from Biogen and its partner company, Eisai, and hundreds of thousands of dollars more in previous years. Other people who testified stated upfront whether or not they had financial conflicts.

Dr. Leslie Norins, founder of a group called Alzheimer’s Germ Quest that supports research, said the lack of disclosure hurts the Alzheimer’s Association’s credibility. “When the association asks the FDA to approve a drug, shouldn’t it have to reveal that it received millions of dollars from the drug company?” he asked.

But Joanne Pike, the Alzheimer’s Association’s chief strategy officer, who testified before the FDA advisory committee about aducanumab without disclosing the contributions, denied that the association was hiding anything or that it supported the drug’s approval because of the drugmakers’ money. Anyone can search the association’s website to find all corporate contributions, she said in an interview.

Pike said her association backs the drug’s approval because its potential to slow patients’ cognitive and functional decline offers substantial benefits to patients and their caregivers, its side effects are “manageable,” and it will spur the development of other, more effective Alzheimer’s treatments.

“History has shown that approvals of first drugs in a category benefit people because they invigorate the pipeline,” she said. “The first drug is a start, and the second and third and fourth treatment could do even better.”

Lurie disputed that. He said lowering the FDA’s standards and approving an ineffective or marginally effective drug merely encourages other manufacturers to develop similar, “me too” drugs that also don’t work well.

Anne Saint says she wouldn’t have risked putting her husband, Mike Saint, on the new Alzheimer’s drug aducanumab because of safety issues. Mike died in September at age 71. (MOLLY SAINT)

The Public Citizen Health Research Group, which opposes approval of aducanumab, has called for an investigation of the FDA’s “unprecedented and inappropriate close collaboration” with Biogen. It asked the inspector general of the Department of Health and Human Services to probe the approval process, which that office said it would consider.

The group also urged the acting FDA commissioner, Dr. Janet Woodcock, to remove Dr. Billy Dunn, an aducanumab advocate who testified about it to the advisory committee, from his position as director of the FDA’s Office of Neuroscience and hand over review of the drug to staffers who weren’t involved in the Biogen collaboration.

Woodcock refused, saying in a letter that FDA “interactions” with drugmakers make drug development “more efficient and more effective” and “do not interfere with the FDA’s independent perspective.”

Although it would be unusual for the FDA to approve a drug after rejection by an FDA advisory committee, it’s not unprecedented, Lurie said. Alternatively, the agency could approve it on a restricted basis, limiting it to a segment of the Alzheimer’s patient population and/or requiring Biogen to monitor patients.

“That will be tempting but shouldn’t be the way the problem is solved,” he said. “If the product doesn’t work, it doesn’t work. Once it’s on the market, it’s very difficult to get it off.”

If the drug is approved, Alzheimer’s patients and their families will have to make a difficult calculation, balancing the limited potential benefits with proven safety issues.

Anne Saint, whose husband, Mike, had Alzheimer’s for a decade and died in September at age 71, said that based on what she’s read about aducanumab, she wouldn’t have put him on the drug.

“Mike was having brain bleeds anyway, and I wouldn’t have risked him having any more side effects, with no sure positive outcome,” said Saint, who lives in Franklin, Tenn. “It sounds like maybe that drug’s not going to work, for a lot of money.”

Their adult daughter, Sarah Riley Saint, feels differently. “If this is the only hope, why not try it and see if it helps?” she said.

Harris Meyer is a Kaiser Health News reporter.

Marisa Taylor: A fountain of youth if you're a mouse

BOSTON

Renowned Harvard University geneticist David Sinclair recently made a startling assertion: Scientific data shows that he has knocked more than two decades off his biological age.

What’s the 49-year-old’s secret? He says his daily regimen includes ingesting a molecule his own research found improved the health and lengthened the life span of mice. Sinclair now boasts online that he has the lung capacity, cholesterol and blood pressure of a “young adult” and the “heart rate of an athlete.”

Despite his enthusiasm, published scientific research has not yet demonstrated the molecule works in humans as it does in mice. Sinclair, however, has a considerable financial stake in his claims being proven correct, and has lent his scientific prowess to commercializing possible life extension products such as molecules known as “NAD boosters.”

His financial interests include being listed as an inventor on a patent licensed to Elysium Health, a supplement company that sells a NAD booster in pills for $60 a bottle. He’s also an investor in InsideTracker, the company that he says measured his age.

Discerning hype from reality in the longevity field has become tougher than ever as reputable scientists such as Sinclair and pre-eminent institutions such as Harvard align themselves with promising but unproven interventions — and at times promote and profit from them.

Fueling the excitement, investors pour billions of dollars into the field even as many of the products already on the market face fewer regulations and therefore a lower threshold of proof.

“If you say you’re a terrific scientist and you have a treatment for aging, it gets a lot of attention,” said Jeffrey Flier, a former Harvard Medical School dean who has been critical of the hype. “There is financial incentive and inducement to overpromise before all the research is in.”

Elysium, co-founded in 2014 by a prominent MIT scientist to commercialize the molecule nicotinamide riboside, a type of NAD booster, highlights its “exclusive” licensing agreement with Harvard and the Mayo Clinic and Sinclair’s role as an inventor. According to the company’s press release, the agreement is aimed at supplements that slow “aging and age-related diseases.”

Further adding scientific gravitas to its brand, the Web site lists eight Nobel laureates and 19 other prominent scientists who sit on its scientific advisory board. The company also advertises research partnerships with Harvard and U.K. universities Cambridge and Oxford.

Some scientists and institutions have grown uneasy with such ties. Cambridge’s Milner Therapeutics Institute announced in 2017 it would receive funding from Elysium, cementing a research “partnership.” But after hearing complaints from faculty that the institute was associating itself with an unproven supplement, it quietly decided not to renew the funding or the company’s membership to its “innovation” board.

“The sale of nutritional supplements of unproven clinical benefit is commonplace,” said Stephen O’Rahilly, the director of Cambridge’s Metabolic Research Laboratories who applauded his university for reassessing the arrangement. “What is unusual in this case is the extent to which institutions and individuals from the highest levels of the academy have been co-opted to provide scientific credibility for a product whose benefits to human health are unproven.”

The Promise

A generation ago, scientists often ignored or debunked claims of a “fountain of youth” pill.

“Until about the early 1990s, it was kind of laughable that you could develop a pill that would slow aging,” said Richard Miller, a biogerontologist at the University of Michigan who heads one of three labs funded by the National Institutes of Health to test such promising substances on mice. “It was sort of a science fiction trope. Recent research has shown that pessimism is wrong.”

Mice given molecules such as rapamycin live as much as 20 percent longer. Other substances such as 17 alpha estradiol and the diabetes drug Acarbose have been shown to be just as effective — in mouse studies. Not only do mice live longer, but, depending on the substance, they avoid cancers, heart ailments and cognitive problems.

“Until about the early 1990s, it was kind of laughable that you could develop a pill that would slow aging,” says University of Michigan biogerontologist Richard Miller. “It was sort of a science fiction trope. Recent research has shown that pessimism is wrong.”

But human metabolism is different from that of rodents. And our existence is unlike a mouse’s life in a cage. What is theoretically possible in the future remains unproven in humans and not ready for sale, experts say.

History is replete with examples of cures that worked on mice but not in people. Multiple drugs, for instance, have been effective at targeting an Alzheimer’s-like disease in mice yet have failed in humans.

“None of this is ready for prime time. The bottom line is I don’t try any of these things,” said Felipe Sierra, the director of the division of aging biology at the National Institute on Aging at NIH. “Why don’t I? Because I’m not a mouse.”

The Hype

Concerns about whether animal research could translate into human therapy have not stopped scientists from racing into the market, launching startups or lining up investors. Some true believers, including researchers and investors, are taking the substances themselves while promoting them as the next big thing in aging.

“While the buzz encourages investment in worthwhile research, scientists should avoid hyping specific [substances],” said S. Jay Olshansky, a professor who specializes in aging at the School of Public Health at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Yet some scientific findings are exaggerated to help commercialize them before clinical trials in humans demonstrate both safety and efficacy, he said.

“It’s a great gig if you can convince people to send money and use it to pay exorbitant salaries and do it for 20 years and make claims for 10,” Olshansky said. “You’ve lived the high life and get investors by whipping up excitement and saying the benefits will come sooner than they really are.”

Promising findings in animal studies have stirred much of this enthusiasm.

Research by Sinclair and others helped spark interest in resveratrol, an ingredient in red wine, for its potential anti-aging properties. In 2004, Sinclair co-founded a company, Sirtris, to test resveratrol’s potential benefits and declared in an interview with the journal Science it was “as close to a miraculous molecule as you can find.” GlaxoSmithKline bought the company in 2008 for $720 million. By the time that Glaxo halted the research in 2010 because of underwhelming results with possible side effects, Sinclair had already received $8 million from the sale, according to Securities and Exchange Commission documents. He also had earned $297,000 a year in consulting fees from the company, according to The Wall Street Journal.

At the height of the buzz, Sinclair accepted a paid position with Shaklee, which sold a product made out of resveratrol. But he resigned after The Wall Street Journal highlighted positive comments he made about the product that the company had posted online. He said he never gave Shaklee permission to use his statements for marketing.

Sinclair practices what he preaches — or promotes. On his LinkedIn bio and in media interviews, he describes how he now regularly takes resveratrol; the diabetes drug metformin, which holds promise in slowing aging, and nicotinamide mononucleotide, a substance known as NMN that his own research showed rejuvenated mice.

Of that study, he said in a video produced by Harvard that it “sets the stage for new medicines that will be able to restore blood flow in organs that have lost it, either through a heart attack, a stroke or even in patients with dementia.”

In an interview with KHN, Sinclair said he’s not recommending that others take those substances.

“I’m not claiming I’m actually younger. I’m just giving people the facts,” he said, adding that he’s sharing the test results from InsideTracker’s blood tests, which calculate biological age based on biomarkers in the blood. “They said I was 58, and then one or two blood tests later they said I was 31.4.”

InsideTracker sells an online age-tracking package to consumers for up to about $600. The company’s website highlights Sinclair’s support for the company as a member of its scientific advisory board. It also touts a study that describes the benefits of such tracking, which Sinclair co-authored.

Sinclair is involved either as a founder, an investor, an equity holder, a consultant or a board member with 28 companies, according to a list of his financial interests. At least 18 are involved in anti-aging in some way, including studying or commercializing NAD boosters. The interests range from longevity research startups aimed at humans and even pets to developing a product for a French skin care company to advising a longevity investment fund. He’s also an inventor named in the patent licensed by Harvard and the Mayo Clinic to Elysium, and one of his companies, MetroBiotech, has filed a patent related to nicotinamide mononucleotide, which he says he takes himself.

Sinclair and Harvard declined to release details on how much money he — or the university — is generating from these disclosed outside financial interests. Sinclair estimated in a 2017 interview with Australia’s Financial Review that he raises $3 million a year to fund his Harvard lab.

Liberty Biosecurity, a company he co-founded, estimated in Sinclair’s online bio that he has been involved in ventures that “have attracted more than a billion dollars in investment.” When KHN asked him to detail the characterization, he said it was inaccurate, without elaborating, and the comments later disappeared from the website.

Sinclair cited confidentiality agreements for not disclosing his earnings, but he added that “most of this income has been reinvested into companies developing breakthrough medicines, used to help my lab, or donated to nonprofits.” He said he did not know how much he stood to make off the Elysium patent, saying Harvard negotiated the agreement.

Harvard declined to release Sinclair’s conflict-of-interest statements, which university policy requires faculty at the medical school to file in order to “protect against any faculty bias that could heighten the risk of harm to human research participants or recipients of products resulting from such research.”

“We can only be proud of our collaborations if we can represent confidently that such relationships enhance, and do not detract from, the appropriateness and reliability of our work,” the policy states.

Elysium advertises both Harvard’s and Sinclair’s ties to its company. It was co-founded by Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor Leonard Guarente, Sinclair’s former research adviser and an investor in Sinclair’s Sirtris.

Echoing his earlier statements on resveratrol, Sinclair is quoted on Elysium’s website as describing NAD boosters as “one of the most important molecules for life.”

Supplement Loophole?

The Food and Drug Administration doesn’t categorize aging as a disease, which means potential medicines aimed at longevity generally can’t undergo traditional clinical trials aimed at testing their effects on human aging. In addition, the FDA does not require supplements to undergo the same safety or efficacy testing as pharmaceuticals.

The banner headline on Elysium’s website said that “clinical trial results prove safety and efficacy” of its supplement, Basis, which contains the molecule nicotinamide riboside and pterostilbene. But the company’s research did not demonstrate the supplement was effective at anti-aging in humans, as it may be in mice. It simply showed the pill increased the levels of the substance in blood cells.

“Elysium is selling pills to people online with the assertion that the pills are ‘clinically proven’” said O’Rahilly. “Thus far, however the benefits and risks of this change in chemistry in humans is unknown.”

“Many interventions that seem sensible on the basis of research in animals turn out to have unexpected effects in man,” he added, citing a large clinical trial of beta carotene that showed it increased rather than decreased the risk of lung cancer in smokers.

Elysium’s own research documented a “small but significant increase in cholesterol,” but added more studies were needed to determine whether the changes were “real or due to chance.” One independent study has suggested that a component of NAD may influence the growth of some cancers, but researchers involved in the study warned it was too early to know.

Guarente, Elysium’s co-founder and chief scientist, told KHN he isn’t worried about any side effects from Basis, and he emphasized that his company is dedicated to conducting solid research. He said his company monitors customers’ safety reports and advises customers with health issues to consult with their doctors before using it.

If a substance meets the FDA’s definition of a supplement and is advertised that way, then the agency can’t take action unless it proves a danger, said Alta Charo, a former bioethics policy adviser to the Obama administration. Pharmaceuticals must demonstrate safety and efficacy before being marketed.

“A lot of what goes on here is really, really careful phrasing for what you say the thing is for,” said Charo, a law professor at the University of Wisconsin. “If they’re marketing it as a cure for a disease, then they get in trouble with the FDA. If they’re marketing it as a rejuvenator, then the FDA is hamstrung until a danger to the public is proven.”

“This is a recipe for some really unfortunate problems down the road,” Charo added. “We may be lucky and it may turn out that a lot of this stuff turns out to be benignly useless. But for all we know, it’ll be dangerous.”

The debate about the risks and benefits of substances that have yet to be proven to work in humans has triggered a debate over whether research institutions are scrutinizing the financial interests and involvement of their faculty — or the institution itself — closely enough. It remains to be seen whether Cambridge’s decision not to renew its partnership will prompt others to rethink such ties.

Flier, the former dean of Harvard Medical School, had earlier heard complaints and looked into the relationships between scientists and Elysium after he stepped down as dean. He said he discovered that many of the board members who allowed their names and pictures to be posted on the company website knew little about the scientific basis for use of the company’s supplement.

Flier recalls that one scientist had no real role in advising the company and never attended a company meeting. Even so, Elysium was paying him for his role on the board, Flier said.

Caroline Perry, director of communications for Harvard’s Office of Technology Development, said agreements such as Harvard’s acceptance of research funds from Elysium comply with university policies and “protect the traditional academic independence of the researchers.”

Harvard “enters into research agreements with corporate partners who express a commitment to advancing science by supporting research led by Harvard faculty,” Perry added.

Like Harvard, the Mayo Clinic refused to release details on how much money it would make off the Elysium licensing agreement. Mayo and Harvard engaged in “substantial diligence and extended negotiations” before entering into the agreement, said a Mayo spokeswoman.

“The company provided convincing proof that they are committed to developing products supported by scientific evidence,” said the spokeswoman, Duska Anastasijevic.

Guarente of Elysium refused to say how much he or Elysium was earning off the sale of the supplement Basis. MIT would not release his conflict-of-interest statements.

Private investment funds, meanwhile, continue to pour into longevity research despite questions about whether the substances work in people.

One key Elysium investor is the Morningside Group, a private equity firm run by Harvard’s top donor, Gerald Chan, who also gave $350 million to the Harvard School of Public Health.

Billionaire and WeWork co-founder Adam Neumann has invested in Sinclair’s Life Biosciences.

An investment firm led by engineer and physician Peter Diamandis gave a group of Harvard researchers $5.5 million for their startup company after their research was publicly challenged by several other scientists.

In its announcement of the seed money, the company, Elevian, said its goal was to develop “new medicines” that increase the activity levels of the hormone GDF11 “to potentially prevent and treat age-related diseases.”

It described research by its founders, which include Harvard’s Amy Wagers and Richard Lee, as demonstrating that “replenishing a single circulating factor, GDF11, in old animals mirrors the effects of young blood, repairing the heart, brain, muscle and other tissues.”

Other respected labs in the field have either failed to replicate or contradict key elements of their observations.

Elevian’s CEO, Mark Allen, said the early scientific data on GDF11 is encouraging, but “drug discovery and development is a time-intensive, risky, regulated process requiring many years of research, preclinical [animal] studies, and human clinical trials to successfully bring new drugs to market.”

Flier worries research in the longevity field could be compromised, although he recognizes the importance and promise of the science. He said he’s concerned that alliances between billionaires and scientists could lead to less skepticism.

“A susceptible billionaire meets a very good salesman scientist who looks him deeply in the eyes and says, ‘There’s no reason why we can’t have a therapy that will let you live 400 or 600 years,’” Flier said. “The billionaire will look back and see someone who is at MIT or Harvard and say, ‘Show me what you can do.’”

Despite concerns about the hype, scientists are hopeful of finding a way forward by relying on hard evidence. The consensus: A pill is on the horizon. It’s just a matter of time — and solid research.

“If you want to make money, hiring a sales rep to push something that hasn’t been tested is a really great strategy,” said Miller, who is testing substances on mice. “If instead you want to find drugs that work in people, you take a very different approach. It doesn’t involve sales pitches. It involves the long, laborious, slogging process of actually doing research.”

KHN senior correspondent Jay Hancock contributed to this report.