‘Tolling, gonging, calling’

Monson, Maine, in 1905

“The rolling, winding roads away from Bangor [Maine] took us through towns with names like Charleston, Dover-Foxcroft, Monson, and Shirley, all with their own quaint, beautifully cinematic set dressing. It was like each was curated from grange hall flea markets and movie sets rife with small-town Americana. Stoic stone war memorials. American flags. Whitewashed, chipping town hall buildings from other centuries. Church bell towers in the actual process of tolling, gonging, calling. To me, the sound was ominous in a remote sort of way, unnamable.”

― Katie Lattari, in her thriller novel Dark Things I Adore

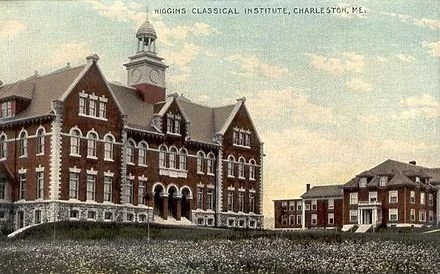

In Charleston, Maine: buildings of the former Higgins Classical Institute, a college-preparatory boarding school that existed from 1837 to 1975.

Llewellyn King: College melds arcane trades with liberal arts

The American College of the Building Arts, in Charleston, S.C.

The Breakers, the famed Newport mansion, and the other great “cottages in the city, provide work for the sort of artisans traded by the American College of the Building Arts.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

It takes years to learn to fashion something out of a block of stone. You may think that you have talent, but it isn’t intuitive. You have to study stone carving, take up the mallet and chisel, waste a lot of rock, and gradually turn from novice to craftsman.

Likewise, you won’t learn the delights of English literature in a week. It takes time.

All of this can be accomplished in one extraordinary place: the American College of the Building Arts, in Charleston, S.C. — a jewel of the South with its many antebellum mansions and other buildings, making it a place of living history.

The college offers a full liberal-arts curriculum plus a specialization in one of six building arts: Classical architecture, blacksmithing, timber framing, carpentry, plaster and stone-cutting. It owes its existence to Hugo, the Category 4 hurricane that slammed into Charleston and much of the rest of the Carolina coast in 1989. Many of Charleston’s treasured homes and buildings were damaged.

Then came the second heartbreak: There was a dearth of craft workers who could put Charleston, like Humpy Dumpty, back together again. The shortage was so acute that it took more than 10 years to restore the city to what it had been pre-Hugo.

The civic pride of the city asserted itself. A group of shocked citizens vowed they wouldn’t go through that again. They would train fine artisans right there in Charleston. But they didn’t want just a trade school; they wanted a seat of learning and restoration to be part of that learning.

They didn’t want to turn out graduates who felt that they had to go through life entering through the back door. No. These would be graduates with a robust degree in liberal arts, as comfortable reading Shakespeare as helping restore a European cathedral built in his day.

So, the American College of the Building Arts was born, in 1999, and it is flourishing and growing. By college size standards, it is minuscule: 120 graduates this year. But in terms of educational creativity, it is huge. It shines a light that shows the way to a new concept of education: students learning a trade they enjoy, that is highly marketable, and also getting the benefits of four years of liberal-arts education.

In April 2018, I visited the college to film an episode of White House Chronicle, on PBS, and was captivated. I had never seen anything like it: a slight young woman working at a 2,000-degree forge, making a beautiful piece of decorative ironwork, inspired by work in a French cathedral; a woman, who had had a previous career in the Coast Guard, carving stone, with an ambition to work on the National Cathedral, in Washington; and a gifted African-American man, a former Marine who had traveled the world, working with big timbers in the framing shop.

Because I have an interest in words, I sat in on a literature course wondering secretly whether it was, perhaps, a bit cursory. It wasn’t. The former Marine timber-framing student said the literature course, taught by Wade Razzi, who has a doctorate degree from Oxford, was his favorite, and among the authors he loved was Charles Dickens.

A friend’s daughter was attracted to the college after learning about it from my television episode. He credits the college with having done wonders for her. She is a star stone carver there, likely headed to work on Liverpool Cathedral.

The college is a beacon for these reasons:

It gives its students a sense of purpose they might not have found otherwise: The reward of making something special and durable.

The college accepts men and women, although Razzi told me women were often the stars. Twenty-five percent of the students are women, and they lead in valedictorians. Five percent are veterans.

About a third of the students, within five years of graduating, start their own contracting businesses. This is so prevalent that the college has added accounting courses so that the young entrepreneurs can keep books.

The college must teach one foreign language, and that is Spanish. In a recent episode of White House Chronicle on the college, Razzi said Spanish is taught because it is essential in the building trades, where many workers are from Latin America.

One of the college’s biggest challenges is recruiting faculty, Razzi, who also serves as chief academic officer, said in that TV episode. Many faculty members come from Europe to teach arcane-in-America trades such as decorative plaster, stone carving and blacksmithing.

Some of these trades are arcane but in great demand from Newport, R.I.’s mansions – called “cottages’’ — to the National Cathedral and the Capitol, to memorial gardens. Artisans are in demand and artisans with liberal-arts credentials are something special: roundly skilled and roundly educated.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

American College of the Building Arts junior carving a stone mantle.

Llewellyn King: History shows that reform is highly perishable

Beacon of learning, practicality and hope: American College of the Building Arts, in Charleston, S.C.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Reform is in the air. Beware of it. Often it evaporates as the generation that spawned it moves on.

I take you back to the 1960s, when reform was everywhere. We came out of that tumultuous decade with high hopes for a better deal. Some reform movements left a lasting impact, but others faded away.

Here, in no order, are what I see as the seminal reforming events of the ’60s.

The anti-Vietnam War movement; the environmental movement; the civil- rights movement; the women’s movement, and the prison-reform movement. Considering what’s happening on the streets of America now, it can be argued that the biggest disappointment was in civil rights, despite what’s been achieved.

To be sure, schools, including colleges, were integrated, and big institutions offered some colorblind promotion. Legislation guaranteeing civil rights, including voting rights, and banning overt segregation in housing, for example, was passed.

But social integration failed. After the riots of 1968, triggered by the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., whites accelerated their exit from cities in droves for the suburbs, in “white flight.”

Much of the civil-rights legislation over time has been whittled away, particularly that associated with President Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society. It was often replaced with harsh policing and an attack on welfare.

It became a myth that The Great Society failed. It didn’t. The Great Society wasn’t given a fair shake before it was replaced with The Great Lockup Society.

Fear of drugs and related crime was greeted in the 1970s and 1980s with a philosophy that it was best to lock people up for a long time with mandatory sentencing and zero tolerance. The burden fell disproportionately on young African-American and Hispanic men.

The young people who’d marched around the White House in opposition to the Vietnam War, and belonged to what was called at the time “the new class,” were going to bring in a new society. They were articulate idealists who wanted a better world.

However, as other problems gripped the national attention, such as energy, the new class matured into the old class. They forgot the heady hopes of the ’60s when they’d dreamed of utopia.

Our politics hardened, too. The whole political apparatus moved to the right. If blacks were thought of at all by whites, it was as though their problems had been solved: Heck, there were black people all over television.

The big issues of health care and education weren’t addressed and if they were, the answer was unhelpful: private health care and private education.

We started graduating an almost unemployable class through the broken public-school systems. Then we said, “See, they’re unemployable, ignorant, and only fit for a few minimum wage jobs like hamburger flipping.” If you are born into poverty and have little enlightened parenting at home, failure is nearly guaranteed.

Not only are we graduating students who can hardly read, but we aren’t telling them what reading is about: living a whole life.

My wife and I were filming a television program at the American College of the Building Arts in Charleston, S.C., a few years ago. This private college should be a template for the future of small colleges. Students study liberal arts in tandem with a trade: blacksmithing, carpentry, classical architecture, plaster, stone carving and timber framing.

One student we interviewed -- who was a little older than most college students (like most of the student body) -- was an African-American who had served in the Marine Corps. “What do you like about college?” I asked. “Dickens,” he replied. He loved the literature component of the liberal arts education. Then, with a winning smile, he added, “They don’t teach that sort of thing in the high schools around here [Charleston].”

Students with a trade tend to start businesses. We were told that about a third of ACBA graduates start a small business within five years of graduation. Business is within the grasp of anyone who has a trade to sell, such as l carpentry, stone carving or metal-working.

Dignity is beyond price and it comes with success in small business. The key is the right kind of education: teaching downhome skills while lighting up the mind.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Chris Powell: ICE's bizarre refusal; 'radical forgiveness'

Connecticut has a failure of immigration-law enforcement just as big as the recent one in San Francisco, although its location -- Norwich -- hasn't been glamorous enough to gain similar attention, despite outstanding journalism by the local newspaper, the Bulletin.

In San Francisco an illegal alien and repeat felon who has been deported from the United States many times has been charged with shooting a young woman to death on a tourist pier. Before the murder city police were holding the illegal alien on other charges, and federal immigration authorities had asked to be informed of his release so they could collect him. But San Francisco is a "sanctuary city" whose political correctness obstructs immigration-law enforcement. So the Feds were not notified and the illegal alien was not deported again as he should have been.

In Norwich an illegal alien who had just been released from prison after serving 17 years in prison for attempted murder in that city was charged there again last month with the murder of a young woman in her apartment. While Connecticut has declared itself a "sanctuary state," its obstruction of immigration-law enforcement does not go as far as San Francisco's.

At least Connecticut will cooperate with federal immigration authorities for the deportation of felons, and the state apparently notified the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) office of this illegal alien's imminent release.

But ICE did nothing about it, and the agency's explanation is contemptible. That is, ICE claims that, upon his release from prison, it couldn't deport the illegal alien now charged with the Norwich murder because he would not produce any documents associating him with his native country, Haiti. So having attempted murder once already in Norwich, this illegal alien was simply set free and ICE forgot about him. Now he is charged with murder itself.

If ICE maintains its excuse -- that illegal aliens can't be deported unless they cooperate by producing adequate documentation -- then every illegal alien in the country can gain permanent residency here simply by destroying his documents.

Norwich's U.S. representative, Joseph D. Courtney, is pressing ICE for a better explanation. He should be joined by the rest of Connecticut's congressional delegation, the state's news organizations, and all concerned citizens. Even in politically correct Connecticut an innocent life must be worth more than this.

XXX

In a recent letter to the editor a reader from Tolland scolded this writer's June 29 column for not having been impressed by the forgiveness given the racist mass murderer in Charleston by the survivors of his victims. "Powell apparently knows little about the teachings of the New Testament," the reader wrote, adding: "Radical forgiveness, even of one's worst enemies, is the way of the cross."

But one can be familiar with the New Testament and willing to let people follow "radical forgiveness" and the way of the cross i their personal lives and still maintain that these things can be contrary to national survival -- and national survival was the point of that column, national survival as sustained by the astounding loyalty of black people to their country despite centuries of abuse, abuse that continued with the mas murder in Charleston.

People can make of forgiveness whatever they will in their personal lives, as a matter of religion, as a psychology of life, or whatever. That won't harm anyone else. But a nation is infinitely bigger than that; it is a collective for which responsibility is shared, and all who are part of it will share its fate.

If one believes that this country, more than any other, aspires to uphold individual liberty within democracy and is, more than any other, the universal nation, then any subversion of it, such as an attempt to terrorize one of its components and start a race war, is the worst treason and, in the national sense, must never be forgiven.

Chris Powell is managing editor of the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester, Conn.