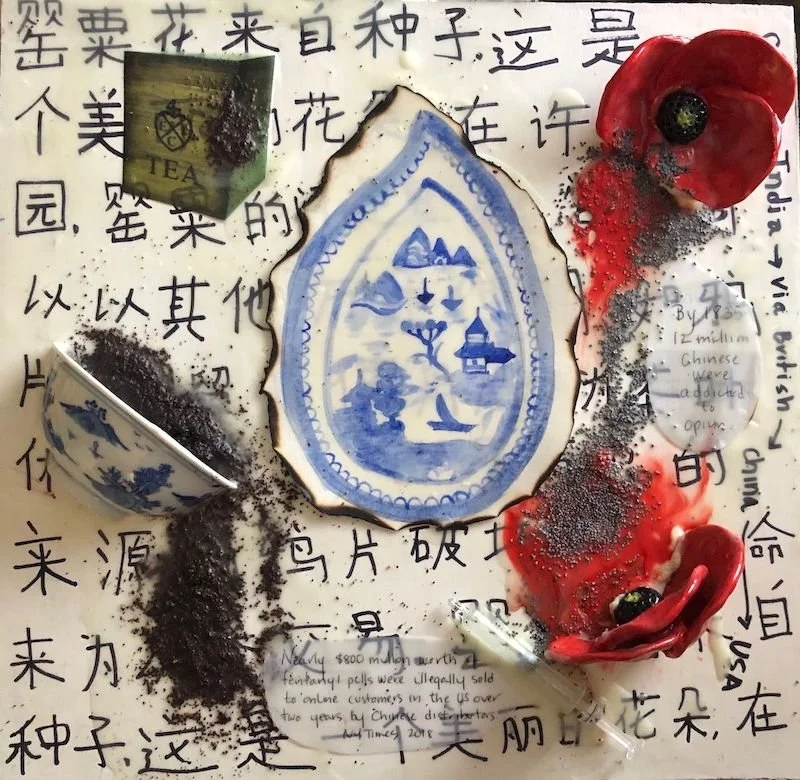

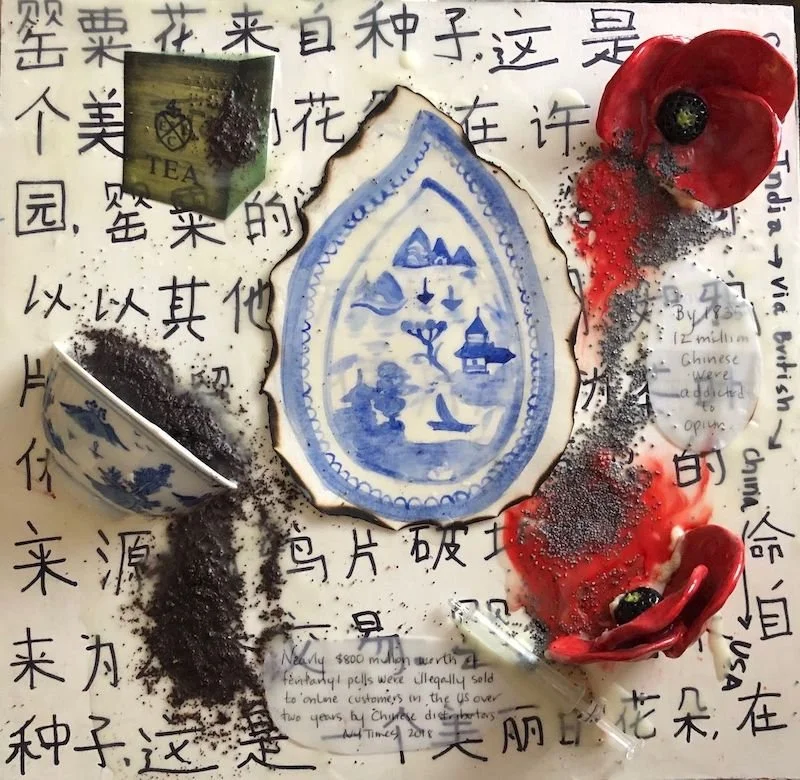

Beauty from New England’s drugged-up China Trade

“China Trade: Opium through the Ages” (encaustic, ceramic made and found objects, tea leaves, poppy seeds on panel), by Cambridge,Mass.-based artist Katrina Abbott.

New England’s “China Trade,’’ in the late 18th Century and the first half of the 19th, created great wealth for some in the region, mostly in and around its ports. Some of the trade involved selling opium to the Chinese. Much of that wealth was invested in what became very lucrative industries, such as textile, shoe and machinery manufacturing and railroads.

In her Web site, Ms. Abbott describes herself thusly:

“Katrina Abbott came to art later in life after her twins were born. Previous to this, she spent 25 years in education, including outdoor education, ocean education at sea and urban public school reform. With a BA in Environmental Biology and a Masters in Botany (studying seaweed!), she reflects her interest in and concern for the natural world in her art. She represents the nature in print, paint, wax ( encaustic) and mosaic. She is a member of the Cambridge Art Association and New England Wax and lives in Cambridge with her husband, their 20 year old boy/girl twins and small brown rabbit named Jarvis.’’

Derby House, in Salem, Mass. Elias Hasket Derby was among the wealthiest and most celebrated of post-Revolutionary War merchants in Salem. He was owner of the Grand Turk, said to be the first New England vessel to be used to trade directly with China. There were many mansions built by merchants in the China Trade, some of which was a drug trade.

—Photo by Daderot

The weight of history in 'Manchester-by-the-Sea'

The Old Burial Ground in Manchester-by-the-Sea, Mass. (Photo by John Phelan)

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary’’ in GoLocal24.com

Some readers may have seen the recently released movie Manchester-by-the-Sea, a devastating family tragedy, but with comic moments, too, and all suffused with a haunting New England atmosphere. I have seen few movies that present a sharper view of the often bleak beauty of New England’s coast and towns or of the anxieties and occasional joys of America’s lower-middle class, New England sub-species.

The film is mostly set in the eponymous Massachusetts town on Greater Boston’s North Shore.

While the official name is the same as in the movie, when I was growing up in Cohasset, across Massachusetts Bay from the town, we only called it “Manchester.’’ I mostly remember the capacious gray-shingled summer places along the town’s rocky headlands and the big Federal Style and Greek Revival houses inland a bit. \

Many of the grandest places in Greater Boston are on the North Shore. That’s where a lot of Boston Brahmins repaired to in the summer; some moved there year-round after they winterized their summer places (when they weren’t in Aiken, S.C., Palm Beach, etc., in the winter). Perhaps because the North Shore ports of Salem and Newburyport had many of the China Trade types who became Boston’s aristocracy, it denizens tended to look down on the South Shore, although Cohasset and Duxbury had/have certain old-money pretensions. So there were social links between the two shores, such as annual sailsbetween the Cohasset and Manchester Yacht Clubs. But someone from Cohasset approaching the shore of Manchester quickly knows he/she is entering more-monied waters than those back home .

The South Shore’s mostly sandy and shallow harbors, as opposed to the deeper rock-rimmed ones north of Boston, made them unattractive for ocean-going ships in the China Trade. Instead, the local big money often came from the shoe business and such things as rope-making. Not as romantic as trading with China!

Manchester has economically struggling people too, and the movie is mostly about them. Like many, perhaps most Americans now, they are downwardly mobile. Too many of them medicate their anxieties, which can move into despair, with booze, opiates and cocaine.

Thoreau wrote that “The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation’’. The characters in Manchester-by-the Sea are not always quiet but they are usually stoical in their suffering from their own mistakes and others’ outrages inflicted on them. But they can still summon up some dark comedy and savor the absurd.

As the movie’s characters walk or drive through Manchester and neighboring towns, you get a sense of the weight of the region’s long history and of the cheeriness of its sunny days alternating with the gloom of its cold, gray and mean winter days darkened by proximity to a hostile ocean. Toward the end of the movie, you even get a sense of the uplift from winter finally succumbing to spring, when the ground has thawed out enough to permit the burial of one of the movie’s characters.

The movie obliquely recalls the regional history that pressed in on Nathaniel Hawthorne (from Salem) in The House of Seven Gables and The Scarlet Letter and William Faulkner’s line “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” New England and the South have a heavy thing on common: the weight of the most complicated histories of any American region except, perhaps, New York City.

One thinks of Faulkner’s novel Absalom, Absalom! in which the Harvard roommate of the Mississippian Quentin Compson says: : “Tell about the South. What's it like there? What do they do there? Why do they live there? Why do they live at all?" You might ask the same question in mid-winter of New Englanders.

In Manchester-by-the Sea, the pertinent past is mostly in the lifetime of the main characters but you can feel the pressure of earlier time, too. And the film might remind us that most of those we encounter have potent psychic pain we know nothing about. If we did, we might pay attention to the old line: “To understand all is to forgive all,’’ though empathy can sometimes be over-rated.