Chuck Collins: I love your music, Taylor, but please ditch your remaining private jet

Taylor Swift’s Dassault7x jet. She sold her other private jet.

Taylor Swift last year.

BOSTON

Via OtherWords.org

I spent a decade, like many parents, chauffeuring pre-teen and teenage girls around to a Taylor Swift soundtrack. I learned every Swift song as it was released and sang along to the chorus in the car. I even went to one of her first stadium concerts with my young Swifties.

Congrats, Taylor, for your talent and decades of consistently great songwriting. You deserve all the accolades and rewards. Here’s my one request: Give up your private jet.

Those young fans of yours that I used to shuttle around are now campaigning against climate change. They understand this is the critical decade to shift our trajectory away from fossil fuels and towards clean energy.

And they need you, once again, to sing a new song.

I know you’re dealing with a lot of crazy conspiracy theories in right-wing media. And you even succeeded in getting Fox News to admit that private-jet travel contributes to climate change, which is no small feat!

They’ve said a lot of nonsense about you, but that part is true. Private jets emit 10 to 20 times more pollutants per passenger than commercial jets. You know it’s wrong — that’s why you cover your face with an umbrella when you’re disembarking.

Maybe it’s even why you decided to sell one of your jets. Why not the other?

We all have that experience of wishing we could be two places at once. I’ve been on a work trip and wished I could zip home for my daughter’s soccer game. But your private flight from your tour in Tokyo to the Super Bowl burned more carbon than six entire average U.S. households will all year.

Like so many challenges in our country, private jet pollution is increasing alongside inequality. According to a report I co-authored for the Institute for Policy Studies, “High Flyers 2023, ‘‘ the number of private jets has grown 133 percent over the last two decades. And just 1 percent of flyers now contribute half of all carbon emissions from aviation.

Should we set off a carbon bomb so that the ultra-rich can fly to their vacation destinations? More and more Americans are answering no. In Massachusetts, a grassroots coalition called Stop Private Jet Expansion at Hanscom and Everywhere is calling on the governor to reject an airport expansion that would serve private jets. It could inspire similar fights nationally. (Hanscom Field is in Bedford, Mass.)

Banning or restricting private jet travel would be one of the easiest paths to reducing emissions if it weren’t a luxury consumed by the most wealthy and powerful people on the planet. But climate advocates are still working to find a way. In Congress, Sen. Ed Markey and Rep. Nydia Velazquez have proposed hiking the tax on private jet fuel to make sure private jet users pay the real financial and ecological costs of their luxury travel.

There’s good news, Taylor: A generation of music stars toured without jets, taking the proverbial tour bus. And it sparked a lot of great songs about this amazing land.

Taylor, if you want to be green, stay on the ground. Your fans will love you and the future generations will thank you.

I believe there’s a song there.

Chuck Collins, based in Boston, directs the Program on Inequality and co-edits the Inequality.org website at the Institute for Policy Studies. .

Chuck Collins: 'Baby Bonds' can help reduce America's intense concentration of wealth

The old Boston Stock Exchange building. The exchange opened in 1834 and closed in 2007, when it was absorbed by NASDAQ.

Via OtherWords.org

BOSTON

The wealthiest 10 percent of Americans hold about 93 percent of all household stock-market wealth in this country, Axios reported recently — a record high.

The Institute for Policy Studies analyzed Fed data and found that the lion’s share of these gains went to the richest 1 percent alone. This elite group owns 54 percent of public equity markets, up from 40 percent in 2002.

The bottom half of the country? They own just 1 percent.

There’s been a lot of chatter about the “democratization” of the public stock market. The Fed estimates that 58 percent of U.S. households have some money in the stock market, mostly through retirement funds such as IRAs and mutual funds.

But that hype is missing a key trend: Nearly all that wealth controlled by the wealthiest 10 percent of us. As Gillian Tett observed in the Financial Times, “If nothing else, these rising concentrations merit far more public debate, since they challenge America’s self-image of its political economy and financial democracy.”

How do we boost the wealth ownership of the bottom half of households? One bold solution is to establish children’s savings accounts, also known as “Baby Bonds.”

New Jersey Sen. Cory Booker and Massachusetts Congresswoman Ayanna Pressley have introduced the American Opportunity Act, a federal Baby Bond bill. Under this proposal, children would be provided with a $1,000 savings account at birth, with annual contributions up to $2,000, depending on family income.

At the age of 18, the proceeds of these accounts would become available to recipients for educational expenses, purchasing a home, or making investments that provide for long-term returns. For example, those funds could be invested in mutual funds and retirement funds to increase the nest eggs for non-wealthy individuals.

A number of states, such as Connecticut, and a few cities, such as Washington, D.C., are already creating baby bond programs. Others have introduced legislation to create them.

Connecticut has a far-reaching program aimed at reducing the state’s racial wealth divide and boosting the wealth of all low-income households. Starting in July 2023, Connecticut began depositing $3,200 into a trust in the name of each new baby born into a household eligible for Medicaid. The program is known by the acronym HUSKY after the popular state college mascot.

Recipients will be able to redeem that capital between the ages of 18 and 30 if they remain Connecticut residents. The “HUSKY Bonds’’ are projected to grow to between $10,000 and $24,000 in value, depending on when they are withdrawn. The funds will be tax-exempt to the beneficiaries and available for investments such as higher education or job training, homeownership and small business start-ups.

Other states that have either introduced Baby Bond legislation or are seriously considering it include California, Massachusetts, Maryland, North Carolina, New Jersey, Nevada, Washington, Wisconsin and Vermont.

Innovative programs such as these can help bust up the dangerous concentration of wealth at the top of our country’s economic ladder. In an age of unprecedented inequality in this country, it’s an idea whose time has come.

Chuck Collins, based in Boston, directs the Program on Inequality and co-edits Inequality.org at the Institute for Policy Studies.

Chuck Collins: Cracking down on Russian oligarchs should include closing U.S. tax havens

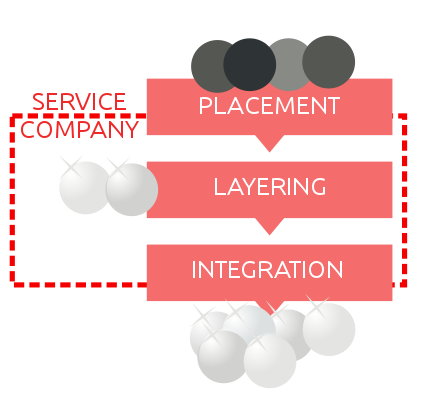

Placing "dirty" money in a service company, where it is layered with legitimate income and then integrated into the flow of money, is a common form of money laundering.

Via OtherWords.org

BOSTON

As part of the sanctions against Russia for its invasion of Ukraine, the United States and its European partners are cracking down on Russian oligarchs. They’re freezing assets and tracking the yachts, private jets and luxury real estate holdings of these Russian billionaires.

“I say to the Russian oligarchs and the corrupt leaders who bilked billions of dollars off this violent regime: no more,” Biden said in his State of the Union address. “We are coming for your ill-begotten gains.”

Targeting Russia’s elites, who have stolen trillions from their own people, is an important strategy to pressure Russian President Vladimir Putin, who himself may be among the wealthiest people on the planet.

But the U.S. faces a major obstacle in this effort: Our own country has become a major destination tax haven for criminal and oligarch wealth from around the world — and not just Russians.

While European Union countries have been increasing transparency and cracking down on kleptocratic capital, the United States is a laggard. As the Pandora Papers disclosed last year, the U.S. has become a weak link in the fight against global corruption.

Delaware, the state President Biden represented in the Senate for 36 years, is the premiere venue for anonymous limited-liability companies that don’t have to disclose who their real beneficial owners are, even to law enforcement. And South Dakota is the home for billionaires creating dynasty trusts, where they can park wealth outside the reach of tax authorities for generations.

Even U.S. charities, as my colleague Helen Flannery wrote recently, have received billions from Russian oligarchs, helping to sanitize their reputations.

Global wealth continues to flood into the United States, especially in luxury real estate. In February, the New York Post did an expose on the luxury real estate holdings of Russian oligarchs in the Big Apple. But oligarchs hide their wealth in real estate all over the country, as well as art, cryptocurrency, and jewelry.

This vast wealth-hiding apparatus would not exist without an enormous enabling class of lawyers, accountants and wealth managers. These “wealth defense industry” professionals are the agents of inequality, the facilitators of the wealth disappearing act. This class of professionals uses their considerable political clout to block reforms.

The first step in fixing the hidden wealth system is ownership transparency — requiring the disclosure of beneficial ownership in real estate, trusts, and companies and corporations. Cities such as Los Angeles are exploring municipal-level disclosure of real estate ownership so they can know who’s buying their neighborhoods.

But we should also shine a spotlight on the wealth defense industry. Days after the release of the Pandora Papers, U.S. lawmakers introduced the ENABLERS Act, which would require such attorneys, wealth managers, real estate professionals, and art dealers to report suspicious activity. The attention on Russian oligarchs has revived interest in this legislation.

If the U.S. wants to clamp down on Russian oligarchs, the first step is to get our own house in order

Chuck Collins, based in Boston, directs the Program on Inequality at the Institute for Policy Studies. He’s the author of The Wealth Hoarders: How Billionaires Pay Millions to Hide Trillions.

John O. Harney: New England and other experts address racial and economic reckoning'

Logo of the Color of Change reform group

BOSTON

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

Even in this time when people presume to be having a “racial reckoning,” signs of enduring racial inequity pop up everywhere. From nagging disparities in health—Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC) die at higher rates than other groups from COVID-19 and are underrepresented in medical research (except in vile experiments such as in the Tuskegee study) … to the steep declines in Black and Latino students submitting the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) … to Black food-service workers experiencing disproportionate short-tipping for enforcing social-distancing rules … inequality reigns. These persistent forces should be a big deal for New England’s Historically White Colleges and Universities, which are rarely called out as HWCUs.

Some help is on the way. Beside targeting $128.6 billion for the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund, $39.6 billion to the Higher Education Emergency Relief Fund, $39 billion for child care and $1 billion for Head Start, the new $1.9 trillion coronavirus relief plan does other less visible things to begin to address structural racism. For example, the package provides Black farmers with debt relief and help acquiring land. Black farmers lost more than 12 million acres of farmland over the past century, attributed to systemic racism and inequitable access to markets.

I’ve been trying to monitor the racial-equity conversation mostly via Zoom since the pandemic began. This mention of aid to Black farmers reminded me of something I heard Chuck Collins say at a webinar convened last month by MIT’s Sloan School of Management via Zoom titled “The Inclusive Innovation Economy: Amplifying Our Voices Through Public Policy’’.

Collins is the director of inequality and the common good at the Institute for Policy Studies and a white man. He told of his uncle getting a 1 percent fixed-rate mortgage in 1949 to buy an Ohio farm—a public investment that led his cousins to get on “America’s wealth-building train.” Black and Brown people did not get the same benefits. Collins suggested that systems such as CARES relief should be examined with a racial-equity lens, as should policies such as raising the minimum wage or forgiving student loans. Unquestionably, Black students struggle more than whites with student debt. But with Capitol Hill debating the right amount of debt to forgive, Collins suggested we need to test how well these changes would affect racial inequity.

Dynastic wealth

Noting that we’re living through an updraft of “dynastic wealth,” Collins asked why the U.S. taxes work income higher than income from investments. He pointed out that “50 families in the U.S. that are now in their third generation of billionaires coming online and that represents a sort of Democracy-distorting and market-distorting concentration of wealth and power.”

That distortion could be partly cushioned with a “dignity floor,” said Collins. “It’s not a coincidence that a society like Denmark has much higher rates of entrepreneurship than the U.S. per capita because they have a social-safety net and because they have social investments that create a decency floor through which people cannot all. So if you want to start a business, you know you can take that leap and not end up living in your car.”

We need to disrupt the narrative of “everyone is where they deserve to be,” said Collins. So many entrepreneurs tell their story from the standpoint of I did this. We need to talk about the web of supports and multigenerational advantages behind their ability to take the step they took.

Color-coded

An audience member asked if a bridge could be built to connect the rich and poor. To this, one of the conversation moderators, Sloan School lecturer and former chief experience and culture officer at Berkshire Bank Malia Lazu, quipped that in the U.S., there’s another dimension: The sides of the bridge are “color-coded.”

Lazu and co-moderator Fiona Murray, associate dean for innovation and inclusion at Sloan, agreed that ironically this is how the policies were designed to work. That’s why we need to change how the systems are wired.

It’s not that Black people are less likely to get loans from banks, but that banks are less likely to give loans to Black people, explained Color of Change President Rashad Robinson. Shifting the subject that way, he said, has led to remedies like financial literacy programs for Black people, rather than changes in the policies of big banks.

Color of Change was formed in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, which, like COVID-19, disproportionately hurt Black and Brown people. Narrative is not static, Robinson said, reminding the audience of what people might have unabashedly said in the workplace about LGBT people just 15 years ago.

Moreover, budgets are “moral documents,” Robinson pointed out. So if you say you’re going to prosecute more corruption crimes than street crime, that has to be reflected in budgets. People of color are not vulnerable, they’ve been targeted, added Robinson, who is working on a report that will look at not only Black pain, but also Black joy and how BIPOC are portrayed in stories on TV.

An audience questioner asked which policies actually embed structural racism. Lazu pointed to the U.S. Constitution’s original clause declaring that any person who was not free would be counted as three-fifths of a free individual. For a more modern example, Robinson noted minimum-wage laws that exclude certain kinds of work, originally farm workers and domestic workers, now work usually done by people of color and women. Structural racism is rooted in how our economy is designed, said Robinson. “An equity focus means we’re not just trying to undo harm but we’re trying to create systems and structures that actually move us forward.”

Afraid to bring children into the world

Also last month, the Boston Social Venture Partners convened a Zoom webinar with affiliates in San Antonio and Denver to discuss how nonprofit leaders have struggled to implement strategies that funders require for diversity, equity and inclusion.

The conversation was moderated by Michael Smith, executive director of the Obama Foundation’s My Brother’s Keeper Alliance, based in Washington, D.C. The alliance was created in 2014 in the aftermath of the killing of Trayvon Martin and aimed at addressing opportunity gaps. It works today against the backdrop of the COVID pandemic and resulting school closures, an economic downturn and police violence in communities of color.

Another Obama fellow, Charles Daniels, the executive director of Boston-based Father’s Uplift, explained: “We have a shortage of clinicians of color in this country—sound, qualified therapists who are able to provide that necessary guidance,” he said. “One of the main requests of single mothers bringing their children to us or fathers entering our agency is that they want a clinician of color, someone who looks like them,” he said. “There are conversations they don’t know necessarily how to have with their loved ones about racism, about oppression, about maintaining their dignity and self-respect.”

Daniels noted that constituents are grappling with what to tell sons about getting pulled over by the police and daughters about what their school may say about hairstyles. “These are conversations that people of color dread this day and age. They wake up trying to parent their inner child and also parent the child who they brought into this world.” He notes that some constituents are actually afraid of having children for these reasons.

A young Black man told Daniels that if he had a choice to be white, he would take it: “I wouldn’t have to worry about my life every time I go to school,” the child suggested, or “an administrator being on my back in school because she’s assuming I’m not doing my work because I don’t care as opposed to me not being able to feed my stomach because I’m hungry.” Daniels said these are real-life situations that young men and single mothers struggle with on a daily basis.

When the federal government recently sent relief stipends, many men of color were left out for not paying child support as if they just didn’t want to pay, when the real reason was they couldn’t afford it.

Growing up as a person of color, you’re taught that you have to be near perfect. You can’t get away with things other populations can, said Daniels. He added: “If someone of color who you’re vetting sends an email with an error, it doesn’t mean they’re incompetent; it probably means they’re doing more than one thing or wearing two hats.” He said he likes funders who offer technical support, as well as authentic conversation, and who don’t avoid the word “racism.”

Giant triplets

Meanwhile, the Quincy Institute, led by retired U.S. Army colonel and noted critic of the Iraq War-turned Boston University professor Andrew Bacevich, held a virtual “Emergency Summit” of public intellectuals to reflect on America Besieged by Racism, Materialism and Militarism—the “giant triplets” identified by Martin Luther King, Jr. in his 1967 speech “Beyond Vietnam.”

Against the backdrop of the Jan. 6 Capitol insurrection, Bacevich began by asking the panelists how those triplets continue to threaten democracy.

One panelist, New York Times contributing writer Peter Beinart, noted that one of the triplets, materialism, while an enormous cultural problem, might not rank as one of the three main ones today because, unlike in the 1960s when people assumed that American living standards would be going up, many today suffer from a lack of materialism and hold very little hope that their situations will improve.

Militarism and racism, however, do persist. As a foreign-policy term, however, “militarist” has been replaced by euphemisms such as “muscular” or “tough-minded.” But militarism is plain to see in the degree to which domestic policing has been affected by military equipment, and veterans return home without decent healthcare. (As an aside, the military has been lauded for well-run coronavirus vaccine sites while the civilian counterparts are often cast as failures. Asked why this is on a recent television news show, Alex Pareene, a staff writer for The New Republic, offered a simple explanation: The U.S. has never disinvested in the military.)

One panelist, the Rev. Liz Theoharis, who is co-chair with Rev. William Barber, of the Poor People’s Campaign, said she would add to King’s triplets, two more demons: ecological devastation and emboldened religious nationalism evidenced on Jan. 6.

Regarding militarism, Theoharis noted that while there’s no military draft per se, there is a “poverty draft” because for many young people, it’s the only way to put food on their table and get an education. Yet, they come home to a lack of opportunity. The majority of single male adults that are homeless in our society are veterans. The military system is “not about the ideals of a democracy and opportunity and possibility and freedom for all, it’s sending poor people, Black people and Latino people to go and fight and kill poor people in other parts of the world,” she said, noting that the U.S. has military bases in more than 800 places. The coronavirus threat has spread in the fissures that we faced before in terms of racism and inequality, which were already claiming lives before the pandemic.

Neta C. Crawford, a professor and chair of political science at Boston University, said democracy is the antidote to militarism, extreme materialism and racism. Members of Congress are tightly connected to military bases and defense contractors in their districts based on the belief that the military-industrial complex creates good jobs. Crawford said we need break this misconception with solid analysis that shows military spending actually produces fewer jobs and what we could be doing instead.

Daniel McCarthy, editor of Modern Age: A Conservative Review and editor-at-large of The American Conservative, noted the irony that U.S. military adventures abroad are framed as antiracist. When he opposed the Iraq War, he was accused of being against Arab democracy and therefore racist. He lamented that we need to find something for the part of industrial America that has been declining, not necessarily related to militarism but to make things that people want to buy.

Justice and belonging in New England

This webinar surfing spree came as NEBHE renewed its focus on diversity, equity and inclusion. The terms “justice” and “belonging” are sometimes also added to the collection of values that used to be disparaged as so much p.c. Moreover, “diversity” is not enough on its own because, as one New England college president recently told his colleagues, people can feel welcomed but also disadvantaged. NEBHE has also looked at the concept of “reparative” justice as a way to recognize that fighting racial oppression should not be responsive to specific past wrongs, but rather, driven by the understanding that the past, present and future exist together.

To be sure, New England will thrive only if its education systems promote inclusion and excellence for learners of all backgrounds, cultures, age groups, lifestyles and learning styles in an environment that promotes justice and equity in a diverse, multicultural world.

John O. Harney is executive editor of The New England Journal of Higher Education.

Chuck Collins/Helen Flannery: America needs emergency charity stimulus

Andrew Carnegie's philanthropy a Puck magazine cartoon by Louis Dalrymple, 1903.

From OtherWords.org

BOSTON

We are living through a time of unprecedented challenges: a major public health crisis and a deepening recession.

Congress has already authorized trillions in stimulus funds. But millions of Americans are still relying on the support of local nonprofits such as food banks and human services. These nonprofits are going to need major infusions of support from charitable donations and foundations.

Fortunately, Congress can help them come up with $200 billion — without costing taxpayers another dime.

We have heard many heartening stories of charitable foundations and individual donors stepping up to fund emergency responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. But this moment has also unmasked a basic design flaw in the U.S. charity system: Donors can contribute to charitable intermediaries that then may sideline the funds for years — or forever.

Right now, there’s an estimated $1.2 trillion in wealth warehoused in private foundations and donor-advised funds. While the donors to these funds have already taken substantial tax breaks for their contributions — sometimes decades ago — there are few incentives to move the money out to charities doing urgent, necessary work.

In fact, America’s 728,000 donor-advised funds, or DAFs — which hold an estimated $120 billion — aren’t legally required to pay out their funds at all, ever. While some DAFs, especially those administered by community foundations, pay out in a timely way, other accounts can languish for years.

America’s 86,000 foundations, which hold over $1 trillion in assets, are mandated by tax law to pay out 5 percent of their assets each year. But many treat that 5 percent as a ceiling, not a floor. And even that 5 percent can include overhead expenses and investments in profit-making companies, rather than direct support for nonprofits.

Remember: these donations are subsidized by ordinary taxpayers. For the wealthiest donors, every dollar parked in their foundation or DAF reduces their tax obligations by as much as 74 cents, leaving people of more modest means to cover public programs.

These wealthy donors have already claimed their tax breaks. Now — in a crisis — ordinary taxpayers need to see the benefit of the funds they subsidized flowing to charities on the ground.

Over 700 foundations have signed a pledge to “act with fierce urgency” to support nonprofit partners and communities hit hardest by COVID-19. And the community foundation sector has set up emergency response systems in all 50 states to channel donations to COVID-19 response efforts.

These are inspiring voluntary efforts. But in this unprecedented emergency, it’s time to mandate an increased flow of funds.

As part of the CARES Act stimulus, Congress increased incentives for charitable giving. In the same spirit, we urge Congress, as part of its next relief bill, to support an “Emergency Charity Stimulus” to inject more than $200 billion into the economy, protect jobs in the nonprofit sector, and help fight the coronavirus disaster.

For three years, Congress should require private foundations to double their annual required payout, from 5 percent to 10 percent. For each one percent increase in payout, an estimated $11 billion to $12.6 billion will flow to charities annually. The same standard should apply to donor advised funds as well.

America’s taxpayers have already effectively paid for these funds. Now we need them deployed to working charities.

Chuck Collins directs the Program on Inequality and the Common Good at the Institute for Policy Studies. Helen Flannery is an Associate Fellow at the Institute for Policy Studies. This op-ed was adapted from Inequality.org and distributed by OtherWords.org.

Chuck Collins: Make the very rich pay their fair share in taxes first

“The Worship of Mammon’’ (1909), by Evelyn De Morgan

Via OtherWords.org

BOSTON

Presidential candidates should take a pledge: The middle class should not pay one dollar more in new taxes until the super-rich pay their fair share.

Already candidates are outlining ambitious programs to improve health care, combat climate change and address the opioid crisis — and trying to explain how they’ll pay for it.

President Trump, on the other hand, wants to give corporations and the richest 1 percent more tax breaks to keep goosing a lopsided economic boom — even as deficit hawks moan about the exploding national debt and annual deficits topping $1 trillion.

Eventually someone is going to have to pay the bills. If history is a guide, the first to pay will be the broad middle class, thanks to lobbyists pulling the strings for the wealthy and big corporations.

Here’s a different idea: Whatever spending plan is put forward, the first $1 trillion in new tax revenue should come exclusively from multimillionaires and billionaires.

Four decades of stagnant wages plus runaway housing and health care costs have clobbered the middle class. In an economy with staggering inequalities — the income and wealth gaps are at their widest level in a century — the middle class shouldn’t be hit up a penny more until the rich pay up.

The biggest winners of the last decade, in terms of income and wealth growth, have not been even the richest 1 percent, but the richest one-tenth of 1 percent. This 0.1 percent includes households with incomes over $2.4 million, and wealth starting at $32 million.

They own more wealth than the bottom 80 percent combined. Yet these multi-millionaires and billionaires have seen their taxes decline over the decades, in part because the tax code favors wealth over work.

This richest 0.1 percent receives two-thirds of their income from investments, while most working families have little capital income and depend on wages. But our rigged system taxes most investment income from wealth at a top rate of about 24 percent — considerably lower than the top 37 percent rate for work.

One way to ensure that the wealthy pay first is to institute a 10 percent surtax on incomes over $2 million. This “multimillionaire surtax” would raise nearly $600 billion in revenue over 10 years, according to an upcoming study from the Tax Policy Center.

The surtax would apply to income earned from work (wages and salaries) and to investment income gained from wealth, including capital gains and dividends. So those with capital income over $2 million would not get a preferential tax rate.C

The multimillionaire surtax is easy to understand, simple to apply, and effective — because it covers all kinds of income, making it difficult for the wealthy to avoid.

And it is laser focused on the super-rich. Anyone earning below $2 million a year would not pay a dime.

As a nation, we will need to raise trillions to protect Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid, and to address urgent priorities such as health care, climate change, child care, higher education, opioid addiction, and more.

The middle class should have 100 percent confidence that they won’t be asked to pony up until Wall Street speculators and billionaires pay the piper. A multimillionaire surtax is a good first step.

Chuck Collins, based in Boston, directs the Program on Inequality at the Institute for Policy Studies.

Chuck Collins: America needs a 'plutocracy prevention' program

Via OtherWords.org

BOSTON

The U.S. is suffering from excessive wealth disorder.

This isn’t your parents’ inequality influenza, but a more virulent strain of extreme disparities of income, wealth, and opportunity.

Just 400 billionaires have as much wealth as nearly two-thirds of American households combined. And just three individuals — Jeff Bezos, Warren Buffet and Bill Gates — have as much wealth as half of all U.S. households put together.

Since the economic meltdown of 2008, the lion’s share of income and wealth growth hasn’t gone just to the top 1 percent — it’s gone to the richest one-tenth of 1 percent. This 0.1 percent includes households with annual incomes starting at $2.2 million and wealth over $20 million.

This group has been the big winner of the last few decades. Its share of national income rose from 6 percent in 1995 to 11 percent in 2015. But their biggest gains are in wealth, increasing their share from 7 percent in 1978 to over 21 percent today.

That’s 210 times their share of the population.

When you have over $20 million, you’ve easily taken care of all your needs and those of the next generation of your family. You’re living in comfort, probably with multiple homes, and don’t want for anything.

It’s at this point we see the telltale signs of excessive wealth disorder. Despite being already comfortable beyond measure, segments of this 0.1 percent will often invest their wealth to rig the political rules to get even more wealth and power.

They contribute the legal maximum donations to politicians and then do an end run around campaign finance laws to siphon even larger sums through “dark money” SuperPACs, using corporate entities that don’t have to disclose donors.

When this donor class demands tax cuts, their political puppets kick into overdrive to deliver the goods.

The 0.1 percenters create charitable foundations that become extensions of their own power and privilege. They undermine the health of the nonprofit sector by controlling a growing share of the charitable giving pie.

They deploy their wealth to help their kids get into elite colleges, both through donations and, as we’ve seen recently, outright bribery.

It’s clear the rest of society needs to intervene. Excessive wealth disorder is wrecking life for the rest of us.

What can we do? We need to put forward a “plutocracy prevention program” — public policies to reduce the power of this top 0.1 percent group.

Some presidential candidates are stepping forward with bold ideas. Senator Elizabeth Warren’s wealth tax idea is a courageous step in this direction. She’s proposed a 2 percent annual tax on wealth over $50 million, with a 3 percent rate on wealth over $1 billion.

Progressive Democrats have proposed raising the top marginal tax rate to 70 percent on households with incomes over $10 million. Senators Kamala Harris and Bernie Sanders both have proposals to make the estate tax more progressive and slow the accumulation of dynastic wealth.

Polls show widespread popular support for these proposals. All of them face steep sledding in a Congress beholden to the top 0.1 percent donor class.

One first step might be a proposal that exclusively targets the 0.1 percent class. How about a 10 percent income surtax on incomes over $2 million, including capital gains?

That’s not as steep as a 70 percent marginal rate, but it would move us in the right direction. It would raise substantial revenue — an estimated $70 billion a year and $750 billion over the next decade — from those with the greatest capacity to pay.

Bringing such a proposal to a vote would require lawmakers to make a clear choice: Are you with the vast majority of voters who believe the super-rich should pay more? Or are you carrying water for the richest 0.1 percent?

Chuck Collins, who is based in Boston, directs the Program on Inequality at the Institute for Policy Studies.

Chuck Collins: Trump's shutdown putting many more people underwater

“The Drowned,’’ 1867 painting by Vasily Perov.

From OtherWords.org

As the government shutdown drags on, the image of federal workers lining up at food pantries has dramatized just how many workers live financially close to the edge.

By one estimate, almost 80 percent of U.S. workers live paycheck to paycheck. Miss one check and you’re taking a second look at what’s in the back of the pantry cupboard.

From federal prison guards in small towns to airline safety inspectors in major cities, the partial government shutdown has forced 800,000 federal workers — and many contractors, too — to survive without a paycheck.

The shutdown is a Trump-made disaster, with an estimated 420,000 “essential workers” required to show up for work without a paycheck. They have full-time responsibilities, which makes finding another part-time job nearly impossible.

Another 380,000 federal workers have been furloughed, including Coast Guard employees that are being encouraged to take on babysitting gigs and organize garage sales. They saw their last paycheck on Dec. 22 and are scrambling to pay rent, mortgages, alimony, and credit card bills, let alone the groceries.

The average federal employee isn’t wealthy, taking home a weekly paycheck of $500, according to American Federation of Government Employees, the union representing affected workers.

The vulnerability they feel isn’t unusual. A majority of the U.S. population is living with very little by way of a savings cushion.

One troubling indicator is the rising ranks of “underwater nation,” households with zero or negative wealth. These families have no savings reserves — they owe more than they own.

The percentage of U.S. households that are “underwater” increased from percent in 1983 to 21.2 percent today. This experience cuts across race, but is more frequent in black and Latino households — including over 32 percent of Latino families and 37 percent of black families.

The next 20 percent of all U.S. households have positive net worth, but not much. Four in ten families couldn’t come up with $400 cash if they needed it for an emergency, according to the Federal Reserve.

Black families are especially vulnerable to economic downturns or delayed paychecks.

Since 1983, the median wealth for a U.S. family has gone down 3 percent, adjusting for inflation. Over the same period, the median wealth for a black family declined a devastating 50 percent, according to “Dreams Deferred,’’ a new study I co-authored for the Institute for Policy Studies. (Meanwhile, the number of households with $10 million or more skyrocketed by 856 percent.)

Unemployment may be low, but it masks a precarious and insecure population. At the root of the problem is growing inequality.

Wages for half the population have been stagnant for over four decades, while expenses such as health care, housing, and other basic necessities have risen. Many families still haven’t fully recovered from the economic meltdown a decade ago.

After going up steadily since World War II, homeownership rates have been falling since 2004. And as with income, homeownership is also heavily skewed towards white families. While the national homeownership rate has virtually remained unchanged between 1983 and 2016, 72 percent of white families owned their home, compared to just 44 percent of black families.

Latino homeownership increased by nearly 40 percent over that time, but it still remains far below the rate for whites, at just 45 percent.

If the partial government shutdown continues for “months or years,” as President Trump threatens, there will be even more stress and hardship on our nation’s most vulnerable families. The bigger challenge is how to ensure our economy enables more people to save and build wealth.

Make no mistake: parts of our economy were on “shutdown” long before the government.

Chuck Collins directs the Program on Inequality at the Institute for Policy Studies.

Chuck Collins: Absentee rich folks are hiding wealth in real estate across America

The Boston skyline from Fenway Park. The skyscraper in the left center is the newish Millennium Tower, where much of the space is held by absentee owners, some foreign. Real estate has long been an attractive investment for money launderers.

— Photo by JJBers

BOSTON

From country farmland to big city skyscrapers, absentee billionaires may be hiding wealth in your town — and driving up your cost of living. rich are hiding trillions in wealth.

You’ve probably heard about their offshore bank accounts, shell corporations, and fancy trusts. But this wealth isn’t all sitting in the likes of the Cayman Islands or Panama. Much of it’s hiding in plain view — maybe even in your town.

America’s big cities are increasingly dotted with luxury skyscrapers and mansions. These multi-million dollar condos are wealth storage lockers, with the ownership often obscured by shell companies.

In Boston, where I live, there’s a luxury building boom. According to a study I just co-authored, out of 1,805 luxury units there — with an average price of over $3 million — more than two-thirds are owned by people who don’t live here.

One-third are owned by shell companies and trusts that mask their ownership. And of these units, 40 percent are limited liability companies (LLCs) organized in Delaware.

Why Delaware?

Criminals around the world set up their shell companies in Delaware, the premiere secrecy jurisdiction in the United States — where you don’t have to disclose who the real owners are. As a result, human traffickers, drug smugglers, and tax evaders all enjoy the anonymous cover of a Delaware company.

Many of these companies use illicit funds to purchase real estate in North American cities to launder their ill-gotten money.

In New York City, dozens of luxury towers have been connected to global money laundering. In Vancouver, Chinese investors disrupted the city’s housing market so badly that the province of British Columbia established a foreign investor tax and a tax on vacant properties.

With European countries now insisting on more transparency, illicit cash is now cascading into the United States. In fact, the U.S. is now the world’s second-biggest tax haven and secrecy jurisdiction, after Switzerland.

The U.S. Treasury Department’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) has increased its scrutiny over real estate markets in Miami, New York, and parts of California, Texas, and Hawaii.

But that just makes the rest of the country more attractive for secret cash — even far from big cities. In a small Vermont town, I met a Russian investor who lives in Dubai. He was buying up thousands of acres of Green Mountain farmland.

Our communities are being fundamentally transformed by land grabs and luxury building booms. These drive up the cost of land in central neighborhoods, with ripple impacts throughout a community. And this worsens the already grotesque inequalities of income, wealth, and opportunity.

Our communities should defend themselves.

Property ownership should have to pass the “fishing license” or “library card” test. In most communities, to get a library card or a fishing license, you need to prove who you are and where you actually live.

In Boston, they’re pretty strict — you need to show a utility bill with your name on it. Cities should require the same for real estate purchases.

At a national level, bi-partisan legislation from Senators Marco Rubio, R-Fla., and Sheldon Whitehouse, D-RI, would require that the identity of real estate owners be disclosed when buyers use shell corporations and pay millions in cash. That would be a welcome development.

Better still, cities should tax luxury real estate transactions on properties selling for over $2 million to fund local services. Such a tax in San Francisco generated $44 million last year that’s been used to fund free community college and help the city’s neglected trees.r

Communities could discourage high-end vacant properties by taxing buildings that sit empty for more than six months a year. Cities like Vancouver have created incentives to house people, not wealth.

We need to defend our communities for the people who live in them, not just store their wealth there.

Chuck Collins co-authored the report “Towering Excess’’ for the Institute for Policy Studies.

Chuck Collins: Learn a trade!

From OtherWords.org

BOSTON

In the classic 1960s movie The Graduate, a family friend offers the recent college graduate, the the character played by Dustin Hoffman, one word of advice in choosing a career: “plastics.”

My advice for today’s high school graduates: “Learn a trade.”

Unfortunately, there’s a historic stigma about “voc-ed,” the result of snobbery toward certain occupations.

Yes, there’s also the shameful practice of tracking low-income whites and people of color into blue-collar jobs while encouraging wealthier white students to attend college. But now there are millions of rewarding, high-paying trade jobs sitting empty.

Instead of training for those, tens of millions of high school graduates are on college autopilot, loading up an average of $37,000 in debt, and graduating without any practical skills.

Not only is our economy suffering for lack of skilled workers, but also a huge number of workers are unhappy and earning below their financial potential.

There are legions of depressed Dilberts out there in cubicle land, sitting in front of computer screens, wondering who will be laid off next. And there are millions of young people sitting in college classrooms dreaming of being somewhere else.

Put these same people in an apprenticeship with a skilled adult and they’ll thrive. Instead of wasting their intelligence in an office, they could deploy it in a bicycle or auto repair garage, woodworking shop, or on a farm or construction site.

Princeton economist Alan Blinder says the job market of the future won’t be divided between people with college degrees and those without, but between work that can be outsourced and work that can’t. “You can’t hammer a nail over the Internet,” he observed. “Nor can you fix a car transmission, rewire a house, install solar panels, or give a patient an injection.”

The value of a liberal arts college education is exposure to a wide range of ideas and knowledge, along with social networks. But college is certainly not the only path to such learning. And four-year residential college today has more in common with a party on a luxury cruise ship than a platform for learning a vocation.

True, today the lifelong earnings of college graduates exceed those who don’t attend college. But there’s no evidence this will be the case going forward. Have you paid an electrician or a plumber anytime lately? There’s a reason they’re hard to find and can command a high wage. It’s called scarcity.

Millions more “green collar” jobs are emerging in our transition to the renewable energy economy. And at some point, our nation will have to repair our aging bridges, roads, and transportation facilities and retrofit buildings to be more energy efficient.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, one third of all new jobs through 2022 will be in construction, health care, and personal care. The fastest growing occupations are solar and wind energy technicians, followed by plumbers, machine tool programmers, HVAC mechanics, and iron and steel workers.

Changing attitudes about different occupations is part of the challenge.

Parents and guidance counselors can start by respectfully talking about the opportunities in trades. They can introduce students to people with satisfying careers in the trades and steer them to useful web resources on the path to trades.

Congress could help by making Pell grants available for short-term job training courses, not just college tuition. It could also restore funding for Tech-Prep, a neglected federal program that supports vocational education.

Let’s dump the old class-biased stereotypes. It takes all kinds of intelligence and advanced training to do a trade. And it can be financially rewarding and enormously satisfying.

Chuck Collins directs the Program on Inequality and the Common Good at the Institute for Policy Studies.

Chuck Collins: Some business leaders agree that reducing inequality is good for the bottom line

For decades, big business leaders have warned that redistributing wealth is bad for business. Taxing the rich to pay for infrastructure and education, they say, will kill the goose that lays the golden egg.

But what if it’s the opposite? What if decades of stagnant wages and growing inequality are scrambling the golden egg and stifling the economy?

A growing body of research suggests that’s exactly what’s happening. And a growing number of business leaders now agree.

Jim Sinegal, the retired CEO of Costco, famously fended off Wall Street pressure to cut wages and made an eloquent case for a higher federal minimum wage. “The more people make, the better lives they’re going to have and the better consumers they’re going to be,” Sinegal told The Washington Post years ago.

“Our country needs less inequality and more opportunity,” agreed former Stride Rite CEO Arnold Hiatt in 2015. “Instead, we’re moving toward a society that will be economically and politically dominated by the sons and daughters of the Forbes 400.”

One of the clearest voices on the business risks of growing inequality is Peter Georgescu, a retired ad man from one of the world’s largest marketing firms. His new book, Capitalists Arise: End Economic Inequality, Grow the Middle Class, Heal the Nation, is a stinging indictment of the way business has been done in our country.

“For the past four decades, capitalism has been slowly committing suicide,” he writes — especially shareholder capitalism, where businesses operate for the benefit of shareholders and no one else.

“Shareholder primacy has become a kind of cancer that needs to be eradicated before it destroys our way of life,” Georgescu warns.

Those views were recently echoed in a letter written to CEOs by Larry Fink, chairman of the investing giant Blackrock.

In January, Fink called on the companies Blackrock invests in to “understand the societal impact of your business as well as the ways that broad, structural trends — from slow wage growth to rising automation to climate change — affect your potential for growth.”

Businesses, Fink exhorted, need a social purpose other than making money.

Reversing inequality will require robust government action at all levels. This includes boosting the minimum wage, fairly taxing big businesses and the rich, and making robust public investments in education, infrastructure, and individual opportunity.

We also need government to crack down on wage theft and discrimination, and to protect the right to organize. Unions and activists have demanded these changes for years.

So what can supportive businesses do? Everything.

They can encourage more employees to be owners. Employees already have an ownership stake at companies such as Publix supermarkets and Southwest Airlines.

They can raise their wage floor to close the monstrous pay gap between top management and average workers — a policy long supported by business guru Peter Drucker. And they can publicly speak out in favor of policies that reduce inequality.

If nothing else, they can stop paying dues to business associations that lobby against sensible taxes and labor protections — like the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and the National Federation of Independent Businesses, which tend to be much more conservative than their members.

Can more business leaders “wake up and take action,” Georgescu challenges? Or will they “continue doing business the ways it’s been done… until the whole system risks falling apart?”

Corporate leaders should stand with ordinary Americans to push for serious public policy to halt the nation’s slide towards greater inequality.

Chuck Collins directs the Program of Inequality and the Common Good at the Institute for Policy Studies.

Chuck Collins: Stop talking about 'winners and losers' in GOP tax scam

Via OtherWords.org

Republicans are pushing a huge corporate tax cut bill through Congress. You might’ve seen a lot of coverage trying to sort out “who wins” and “who loses.”

All that misses the point.

The driving motivation behind this bill, rhetoric and packaging aside, is to deliver a whopping $1 trillion tax cut for a few hundred badly behaved global corporations — and another half a trillion to expand tax breaks and loopholes for multi-millionaires and billionaires.

All the other features of proposed tax legislation are either bribes (“sweeteners”) to help pass the bill or “pay fors” to offset their cost.

The news media has been talking about “winners and losers” like this were some sort of high-minded tax reform process with legitimate trade-offs, as in 1986.

But this isn’t tax reform. This is a money grab by powerful corporate interests.

The key question isn’t who wins and loses, but whether we should undertake any of these trade-offs to give massive tax breaks to companies like Apple, Nike, Pfizer and General Electric — companies whose loyalty to U.S. communities and workers is historically abysmal.

These companies have been dodging their taxes for decades while small businesses and ordinary taxpayers pick up their slack to care for our veterans, maintain our infrastructure, and educate the next generation.

Apple alone is holding $250 billion in offshore subsidiaries to reduce its taxes.

For wealthy individuals, the proposed House tax bill eliminates the federal estate tax, which is paid exclusively by families with over $11 million, mostly residing in coastal states.

It eliminates the Alternative Minimum Tax, a provision that ensures that wealthy taxpayers chip in at least a few dollars after gaming all their possible deductions.

And while the top tax rate on high earners remains roughly the same, Congress is proposing to open up a “pass through loophole” that will enable wealthy people and their tax accountants to convert their income to be taxed at a lower tax rate.

We should avoid distracting debates over whether to reform one provision or another, such as the home mortgage interest deduction. The real estate industry understands the score. “These corporations are getting a major tax cut, and it’s getting paid for by the equity in American homes,” said Jerry Howard, chief executive of the National Association of Home Builders.

Reforming the home mortgage interest deduction makes a lot of sense — the current tax break mostly benefits the already wealthy and fails to expand homeownership. But we shouldn’t restructure housing tax incentives to pay for a massive tax cut for billionaires and badly behaved global corporations.

Nor should we eliminate the deductibility of student debt, eliminate the deduction for state and local taxes, or require families with catastrophic health expenses to pay more to reduce taxes on big drug companies and Jeff Bezos of Amazon. This tax bill would do all of those things.

The good news is people aren’t falling for the marketing baloney that this tax cut will help the middle class. Fewer than 30 percent of voters support these tax cuts, and solid majorities believe that the wealthy and global corporations should pay more taxes, not less.

But this won’t stop Republicans who care more about their campaign contributors than they do about voters.

If the GOP majority in Congress were responsive to voters, they’d invest in updating our aging infrastructure and in skills-based education, as we did after World War Two. Instead of saddling the next generation with tens of thousands in student debt, real leaders would be figuring out how to lift up tomorrow’s workers and entrepreneurs, just as we did in previous generations.

Under this tax plan, small business and ordinary taxpayers will be the big losers. That’s the only score that matters.

Chuck Collins directs the Program on Inequality at the Institute for Policy Studies and co-edits Inequality.org.

Chuck Collins: A guide to the coming tax heist

-- Bundesarchiv, Bild 102-12762 / CC-BY-SA 3.0

Via OtherWords.org

For 40 years, tax cutters in Congress have told us, “we have a tax cut for you.” And each time, they count on us to suspend all judgment.

In exchange, we’ve gotten staggering inequality, collapsing public infrastructure, a fraying safety net, and exploding deficits. Meanwhile, a small segment of the richest one tenth of 1 percent have become fabulously wealthy at the expense of everyone else.

Ready for more?

Now, Trump and congressional Republicans have rolled out a tax plan that the independent Tax Policy Center estimates will give 80 percent of the benefits to the richest 1 percent of taxpayers.

The good news is the majority aren’t falling for it this time around. Recent polls indicatethat over 62 percent of the public oppose additional tax cuts for the wealthy and 65 percent are against additional tax cuts to large corporations.

Here’s the independent thinker’s guide to the tax debate for people who aspire to be guided by facts, not magical thinking. When you hear congressional leaders utter these claims, take a closer look.

“Corporate tax cuts create jobs.”

You’ll hear that the U.S. has the “highest corporate taxes in the world.” While the legal rate is 35 percent, the effective rate — the percentage of income actually paid — is closer to 15 percent, thanks to loopholes and other deductions.

The Wall Street corporations pulling out their big lobbying guns have a lot of experience with lowering their tax bills this way, but they don’t use the extra cash to create jobs.

The evidence, as my Institute for Policy Studies colleague Sarah Anderson found, is that they more often buy back their stock, give their CEOs massive bonuses, pay their shareholders a bigger dividend, all the while continuing to lay off workers.

“Bringing back offshore profits will create jobs.”

Enormously profitable corporations such as Apple, Pfizer and General Electric have an estimated $2.64 trillion in taxable income stashed offshore. Republicans like to say that if we give them a tax amnesty, they’ll bring this money home and create jobs.

Any parent understands the folly of rewarding bad behavior. Yet that’s what we’re being asked to do.

When Congress passed a “repatriation tax holiday” in 2004, these same companies gave raises to their CEOs, raised dividends, bought back their stock, and — you guessed it — laid off workers. The biggest 15 corporations that got the amnesty brought back $150 billion while cutting their U.S. workforces by 21,000 between 2004 and 2007.

For decades now, those big corporations have made middle class taxpayers and small businesses pick up the slack for funding care for veterans, public infrastructure, cyber security, and hurricane mop-ups. Let’s not give them another tax break for their trouble.

“Tax cuts pay for themselves.”

Members of Congress who consider themselves hard-nosed deficit hawks when it comes to helping hurricane victims or increasing college aid for middle class families are quick to suspend basic principles of math when it comes to tax cuts for the rich.

The long discredited theory of “trickledown economics” — the idea that tax cuts for the 1 percent will create sufficient economic growth to pay for themselves — is rising up like zombies at Halloween. As the economist Ha Joon Chang observed, “Once you realize that trickle-down economics does not work, you will see the excessive tax cuts for the rich as what they are — a simple upward redistribution of income.”

“Abolishing the estate tax will help ordinary people.”

This is the biggest whopper of them all. The estate tax is only paid by families with wealth starting at $11 million and individuals with $5.5 million and up. There is no credible economic argument that this will have any positive impact on the economy, but it would be a huge boon for billionaire families like the Trumps.

This tax cut plan is an unprecedented money grab. Whether the heist happens, is entirely up to the rest of us.

Chuck Collins directs the Program on Inequality at the Institute for Policy Studies and co-edits Inequality.org.

Chuck Collins: Rich folks in overalls seek to kill estate tax

Via OtherWords.org

After this summer, President Trump and the Republican Congress have one big item on their agenda: taxes. Specifically, cutting them for the rich.

One tax they’ve got in their crosshairs is the estate tax — which they malign as “the death tax.” But it’s nothing of the sort.

Passed a century ago at the urging of President Theodore Roosevelt, the estate tax is a levy on millionaire inheritances. It puts a brake on the concentration of wealth and political power, and raises substantial revenue — over a quarter of a trillion dollars over the next decade, if it’s kept — from the richest one tenth of 1 percent.

Yet lobbyists are trying to put a populist spin on their effort to abolish this tax, which is paid exclusively by millionaires and billionaires. Puzzlingly, they’re deploying farmers as props and claiming that the tax means the “death of the family farm.”

The accusation is pure manure.

Only households with wealth starting at $11 million (and individuals with wealth over $5.5 million) are subject to the tax. “This hurts a lot of farmers,” claimed Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin. “Many people have to sell their family farm.”

But a new report by President Trump’s own U.S. Department of Agriculture shows this claim is bull. Only 4 out of every 1,000 farms will owe any estate tax at all — and the effective tax rate on these small farms is a modest 11 percent.

Of those few farms, most have substantial non-farm income, according to the report — think billionaire Ted Turner’s ranch in Montana. And estate tax opponents haven’t been able to identify a single example of a farm being lost because of the estate tax.

Still, the rodeo continues.

When the House Ways and Means Committee staged a July hearing against the estate tax, they summoned South Dakota farmer Scott Vanderwal to talk about the woes of the estate tax. The problem was, as Vanderwal himself revealed, his farm wouldn’t even be subject to the tax.

In 2014, right-wing election groups ran $1.8 million worth of ads featuring farmer John Mahan of Paris, Ky. “For our family farms to survive, we’ve got to get in this fight” to end the death tax,' he said.

What the ad fails to disclose is that Mahan is the 15th biggest recipient of farm subsidies in Bourbon County, taking $158,213 of taxpayer money between 1995 and 2014. While some farm subsidies promote price stability and conservation practices, the bulk of funds go to the richest 1 percent of farmers and corporate agricultural operations.

Farm organizations such as the National Farmers Union and the American Family Farm Coalition support retaining the estate tax. They believe the concentration of farmland and farm subsidies has created unfair corporate farm monopolies across rural America.

“The National Farmers Union, through its grassroots policy, respects what the estate tax represents,” said union president Roger Johnson in testimony to the Treasury Department. “We are not opposed to the estate tax.”

When defenders of the estate tax have proposed a “carve out” to exempt any remaining farms, the anti-tax crusaders oppose it. They don’t want to lose their fig leaf.

All this farm talk mystifies who actually pays the tax. Most estate taxpayers live in big cities and wealthy states such New York, Florida, and California. Few have probably ever driven a tractor.

Instead of farmers in overalls, picture Tiffany Trump. If Congress abolishes the estate tax, the president’s children stand to inherit billions more.

In the coming tax debate, watch out for the advertisements and sound bites about farmers and the estate tax. The tax lobbyists for billionaires will be pulling the strings.

Chuck Collins is a senior scholar at the Institute for Policy Studies and a co-editor of Inequality.org. He’s the author of the recent book Born on Third Base.

Chuck Collins: America's crumbling infrastructure and the very rich

Via OtherWords.org

If you find yourself traveling this summer, take a closer look at America’s deteriorating infrastructure — our crumbling roads, sidewalks, public parks and train and bus stations.

Government officials will tell us “there’s no money” to repair or properly maintain our tired infrastructure. Nor do we want to raise taxes, they say.

But what if billions of dollars in tax revenue have gone missing?

New research suggests that the super-rich are hiding their money at alarming rates. A study by economists Annette Alstadsaeter, Niels Johannesen, and Gabriel Zucman reports that households with wealth over $40 million evade 25 to 30 percent of personal income and wealth taxes.

These stunning numbers have two troubling implications.

First, we’re missing billions in taxes each year. That’s partly why our roads and transit systems are falling apart.

Second, wealth inequality may be even worse than we thought. Economic surveys estimate that roughly 85 percent of income and wealth gains in the last decade have gone to the wealthiest one-tenth of the top 1 percent.

That’s bad enough. But what if the concentration is even greater?

Visualize the nation’s wealth as an expansive and deep reservoir of fresh water. A small portion of this water provides sustenance to fields and villages downstream, in the form of tax dollars for public services.

In recent years, the water level has declined to a trickle, and the villages below are suffering from water shortages. Everyone is told to tighten their belts and make sacrifices.

Deep below the water surface, however, is a hidden pipe, siphoning vast amounts of water — as much as a third of the whole reservoir — off to a secret pool in the forest.

The rich are swimming while the villagers go thirsty and the fields dry up.

Yes, there are vast pools of privately owned wealth, mostly held by a small segment of super-rich Americans. The wealthiest 400 billionaires have at least as much wealth as 62 percent of the U.S. population — that’s nearly 200 million of us.

Don’t taxpayers of all incomes under-report their incomes? Maybe here and there.

But these aren’t folks making a few dollars “under the table.” These are billionaires stashing away trillions of the world’s wealth. The latest study underscores that tax evasion by the super-rich is at least 10 times greater — and in some nations 250 times more likely — than by everyone else.

How is that possible? After all, most of us have our taxes taken out of our paychecks and pay sales taxes at the register. Homeowners get their house assessed and pay a property tax.

But the wealthy have the resources to hire the services of what’s called the “wealth defense industry.” These aren’t your “mom and pop” financial advisers that sell life insurance or help folks plan for retirement.

The wealth defenders of the super-rich — including tax lawyers, estate planners, accountants, and other financial professionals — are accomplices in the heist. They drive the getaway cars, by designing complex trusts, shell companies, and offshore accounts to hide money.

These managers help the private jet set avoid paying their fair share of taxes, even as they disproportionately benefit from living in a country with the rule of law, property rights protections, and public infrastructure the rest of us pay for.

Not all wealthy are tax dodgers. A group called the Patriotic Millionaires advocates for eliminating loopholes and building a fair and transparent tax system. They’re pressing Congress to crack down on tax evasion by the superrich.

Their message: Bring the wealth home! Stop hiding the wealth in offshore accounts and complicated trusts. Pay your fair share to the support the public services and protections that we all enjoy.

Chuck Collins is a senior scholar at the Institute for Policy Studies and a co-editor of Inequality.org. He’s the author of the recent book Born on Third Base.

Chuck Collins: Healthcare costs, not taxes, are the big hit on businesses

Members of the House GOP were in a hurry on May 4 to pass their bill to gut Obamacare. They rushed it through before anyone even had a chance to check its cost or calculate its impact on people’s access to insurance.

Their urgency, however, had little to do with health care. The real reason for the rush? To set the table for massive tax cuts.

Indeed, the House health plan would give a $1 trillion boon to wealthy households and pave the way for still bigger corporate tax cuts to come, as part of the so-called “tax reform” they’re pushing.

Meanwhile, dismantling the Affordable Care Act will cause up to 24 million people to lose their health coverage, according to the non-partisan Congressional Budget Office. (Though even that estimate is based on the less extreme version of the bill that failed to pass in April. The new plan may be even worse.)

Why would a GOP politician support an unpopular bill that fewer than 20 percent of voters think is a good idea? Why risk angry constituents showing up at town hall meetings?

Put simply, to please their wealthy donors and Wall Street corporations. For complex legislative reasons, repealing Obamacare’s taxes on the rich first will make it easier for them to slash corporate taxes next.

As the “tax reform” debate begins, prepare for sermons about how cutting taxes for rich and global corporations will be great for the economy. Slashing the corporate tax rate, we’ll be told, will boost U.S. competitiveness.

But if Congress were really concerned about the economy, policy wouldn’t be driven by tax cuts. The real parasite eating the insides of the U.S. economy isn’t taxes, billionaire investor Warren Buffett explained recently, but health care.

In fact, taxes have been steadily going down, especially for the very wealthy and global corporations. “As a percent of GDP,” Buffett told shareholders of his investment firm, the corporate tax haul “has gone down.” But “medical costs, which are borne to a great extent by business,” have increased.

In 1960, corporate taxes in the U.S. were about 4 percent of the economy. Today, they’re less than half that. As taxes have fallen, meanwhile, the share of GDP spent on health care has gone from 5 percent of the economy in the 1960s to 17 percent today.

These costs are the real “tax” on businesses. As any small business owner can tell you, health care costs are one of the biggest expenses in maintaining a healthy and productive work force.

Yet the GOP bill will weaken healthcare coverage and regulation, which will increase costs and hurt U.S. companies.

U.S. employers, remember, must compete with countries that have superior universal health insurance for their citizens and significantly lower costs. While health care eats up 17 percent of the U.S. economy, it’s around just 11 percent in Germany, 10 percent in Japan, 9 percent in Britain and 5.5 percent in China.

No wonder Buffett concluded that “medical costs are the tapeworm of American economic competitiveness.”

Buffett observed that the House healthcare bill would give him an immediate $680,000 annual tax cut, a break he doesn’t really need, while only allowing that tapeworm to bore deeper.

For all its limitations, the Affordable Care Act has expanded coverage and the quality of life for millions of Americans. It’s also put in place important provisions to contain exploding health care expenses, slowing the rise of costs.

The GOP plan to reduce coverage and deregulate health care will take us in the wrong direction. That’s a pretty poor bargain for yet another tax cut for the richest Americans.

Chuck Collins is a senior scholar at the Institute for Policy Studies and a co-editor of Inequality.org. He’s the author of the recent book Born on Third Base.

Chuck Collins: Welcome to underwater nation

Via OtherWords.org

Are you or a loved one having trouble staying afloat? You’re truly not alone.

While the media reports low unemployment and a rising stock market, the reality is that almost 20 percent of the country lives in “Underwater Nation,” with zero or even negative net worth. And more still have almost no cash reverses to get them through hard times.

This is a source of enormous stress for many low and middle-income families.

Savings and wealth are vital life preservers for people faced with job loss, illness, divorce, or even car trouble. Yet an estimated 15 to 20 percent of families have no savings at all, or owe more than they own.

They’re disproportionately rural, female, renters, and people without a college degree. But the underwater ranks also include a large number of people who appear to be in the stable middle class. Health challenges are a major cause of savings depletion for these people, both in medical bills and lost wages.

Plenty more Americans could be vulnerable.

A financial planner will advise you to put aside three months of living expenses in financial reserves, just in case. So if your living expenses are $2,000 a month, you should try to have $6,000 in “liquidity” — money you can easily get to in an emergency.

But 44 percent of households don’t have enough funds to tide themselves over for three months, even if they lived at the poverty level, according to the Assets and Opportunity Scorecard.

Even having a positive net worth doesn’t mean you can always tap these funds, especially if wealth takes the form of home equity or owning a car.

A Bankrate survey found that 63 percent of U.S. households lack the cash or savings to meet a $1,000 emergency expense. They’d have to borrow from a friend or family, or put costs on a credit card.

Seven percent of U.S. homeowners are underwater homeowners, with mortgage debt higher than the value of their homes. And more and more people have taken on credit card debt to pay the bills. Meanwhile, student debt is rising rapidly and is projected to become one of the biggest factors in negative wealth.

Conservative scolds will blame individuals for “living beyond their means” and being financially irresponsible. And individual behavior is important. But the financial stresses facing millions of families are more likely the result of four decades of stagnant incomes.

Half the workers in this country haven’t shared in the economic gains that have mostly gone to the rich. Their real wages have stayed flat while health care, housing, and other expenses continue to rise.

So not everyone is on the edge at this time of dizzying inequality, after all. The 400 wealthiest billionaires in the U.S. have as much wealth together as the bottom 62 percent of the population.

This is only possible because of the expanding ranks of drowning Americans.

Some politicians will scapegoat immigrants or other vulnerable people for this suffering. When this happens, hold on tight to your purse or wallet. They’re trying to distract you from the rich and powerful elites who are rigging the rules to get more wealth and power.

They want to deflect your attention away from the reality that your economic pain is the result of deliberate government rules that give more tax cuts to the super-rich and global corporations, keep wages down, push up tuition costs, and let corporations nickel and dime you for all you’re worth.

Congress and the Trump administration are proposing to cut health care, pass more tax cuts for the rich, and give global corporations even more power over you. They promise benefits will “trickle down.”

Unless we speak up, the only trickle will be the expansion of Underwater Nation.

Chuck Collins is a senior scholar at the Institute for Policy Studies and a co-editor of Inequality.org. He’s the author of the recent book Born on Third Base.

Chuck Collins: Wall St., Trump hope that you've forgotten 2008

This first ran in OtherWords.org

Remember 2008 — the bank bailouts, the spiking unemployment rate, the stock market free fall?

Maybe you lost a job, got a pay cut, or saw your retirement savings or home value evaporate. Maybe you even lost your home altogether, or saw your small business wither and die.

It’s a hard thing to let go. But Wall Street is hoping you’ve already forgotten it.

That’s because their allies in Congress and the Trump administration are poised to scrap the reforms that lawmakers put in place to prevent another meltdown.

For starters, they’re trying to gut the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, the first independent agency with the sole mandate of protecting consumers against scam artists, predatory lenders, and bad actors in the financial sector.

The agency proved its mettle last year, when it caught Wells Fargo — the second biggest bank in the country — creating millions of bogus accounts without their customers’ permission. The bureau exposed that cheating and put an end to it.

Dodd-Frank, the law that created the bureau, also made rules to keep banks from making risky bets with your money.

For instance, it requires banks to keep some skin in the game by maintaining a 5 percent stake in loans they originate, so they have a stake in the success of the borrower and the loan. It also encourages banks to keep some cash on hand in case of emergencies, just like the rest of us try to do at home.

Yet lately, bankers have been complaining that financial regulation is hurting the economy. Gary Cohn, a former Goldman Sachs president — and now a Trump economic adviser — whined recently that banks are being forced to “hoard capital.”

If maintaining a prudent reserve is hoarding, then yes. And that’s a good thing.

Bankers like Cohn say abolishing these rules will help ordinary consumers. When you hear things like that, hold tight to your wallets and purses.

The truth is, cheap credit is abundant. The commercial and industrial business industries are booming. Credit card and auto lending are at record highs, and mortgage loans are almost back to their pre-2008 crisis high.

If that’s not enough for Wall Street lenders who want to gamble, they should go to the casino. And if venture capitalists want to take great risks in search of great rewards, blessings upon them. But they shouldn’t expect the rest of us to bail them out after their next binge.