Llewellyn King: On the 50th Earth Day, grounds for hope amidst the mess

President Nixon and his wife, Patricia, plant a tree on the White House grounds to mark the first Earth Day, in 1970. The Republican Party had many environmentalists back then. In the same year, Nixon signed into law the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency.

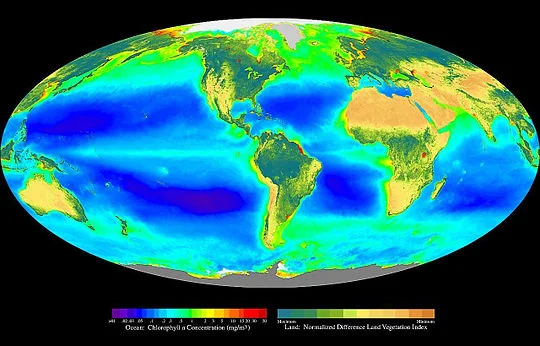

On the face of it, there isn’t much to celebrate on April 22, the 50th anniversary of Earth Day. The oceans are choked with invisible carbon and plastic which is very visible when it washes up on beaches and fatal when ingested by animals, from whales to seagulls.

On land, as a run-up to Earth Day, Mississippi recorded its widest tornado – two miles across -- since measurements were first taken, and the European Copernicus Institute said an enormous hole in the ozone over the Arctic has opened after a decade of stability.

But perversely, there’s some exceptionally good news. Because of the cessation of so much activity, due to the coronavirus pandemic, the air has cleared dramatically; cities around the world, including Mumbai and Los Angeles, are smog-free. Also, the murk in the waters of Venice’s canals and the waves from motorboats are gone, revealing fish and plants in the clear Adriatic water.

Jan Vrins, global energy leader at Guidehouse, the world-circling consultancy, was so excited by the clearing that he posted and tweeted a picture taken from a town in the Punjab where Himalayan peaks are visible for the first time in 30 years.

The message here is very hopeful: With some moderation in human activity, we can save the environment and ourselves.

The sense of gloom and hopelessness that has attended a litany of environmental woes needn’t be inevitable. Mitigating conduct in industry and, particularly in the energy sector, can have a huge impact quickly; transportation will take longer. Vrins says the electric utility industry -- a source of so much carbon -- is now almost entirely engaged in the fight against global warming. Just five years ago, he says, they weren’t all fully committed to it.

Another Guidehouse consultant, Matthew Banks, is working with large industrial and consumer companies on reducing the impact of packaging as well as the energy content of consumer goods. Among his clients are Coca-Cola, McDonald’s and Johnson & Johnson. The latter, he says, has been working to reduce product footprint since 1995.

“This is an important moment in time,” Banks says. “Folks have talked about this as being The Great Pause and I think on this Earth Day, we need to think about how that bounce back or rebound from the Great Pause can be done in a way that responds to the climate crisis.”

I was on hand covering the first Earth Day, created by Wisconsin Sen. Gaylord Nelson, a Democrat, and its national organizer, Denis Hayes. It came as a follow-on to the environmental conscientiousness which arose from the publication of Rachel Carson’s seminal book Silent Spring, in 1962. That dealt with the devastating impact of the insecticide DDT.

Richard Nixon gave the environmental movement the hugely important National Environmental Policy Act of 1969. With that legislation, and the support of people like Nelson, the environmental movement was off and running – and sadly, sometimes running off the rails.

One of the environmentalists’ targets was nuclear power. If nuclear was bad, then something else had to be good. At that time, wind turbines -- like those we see everywhere nowadays -- hadn’t been perfected. Early solar power was to be produced with mirrors concentrating sunlight on towers. That concept has had to be largely abandoned as solar-electric cells have improved and the cost has skidded down.

But in the 1970s, there was reliable coal, lots of it. As the founder and editor in chief of The Energy Daily, I sat through many a meeting where environmentalists proposed that coal burned in fluidized-bed boilers should provide future electricity. Natural gas and oil were regarded as, according to the inchoate Department of Energy, depleted resources. Coal was the future, especially after the energy crisis broke with the Arab oil embargo in the fall of 1973.

Now there is a new sophistication. It was growing before the coronavirus pandemic laid the world low, but it has gained in strength. As Guidehouse’s Vrins says, “We still have climate change as a ‘gray rhino’, a big threat to our society and the world at large. I hope that utilities and all their stakeholders will increase their urgency of addressing that big threat which is still ahead of us.”

Happy birthday Earth Day — and many more to come.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

--

Co-host and Producer

"White House Chronicle" on PBS

Llewellyn King: Regulation can give a big push to creativity and innovation

The Exxon Valdez, aground and leaking massive amounts of oil in Prince William Sound, Alaska.

There is a paradox of regulation clearly not known in the Trump White House. It is this: Regulation can stimulate creativity and move forward innovation.

This has been especially true of energy. Ergo, President Donald Trump's latest move to lessen the impact of regulation on energy companies may have a converse and debilitating impact.

Consider these three examples:

When Congress required tankers to have double hulls, after the Exxon Valdez oil spill in Alaska's Prince William Sound, in 1989, the oil companies and their lobbyists wailed that it would push up the price of gas at the pump.

Happily, the government held tough and soon oil spills in from tanker punctures were almost eliminated.

The cost? Fractions of a penny per gallon, so small they can not be easily found.

Victory to regulation, the environment and common sense. In due course, the oil companies took out advertisements to boast of their environmental sensitivity by double-hulling their tankers.

When the Environmental Protection Agency mandated a 75-percent reduction in hydrocarbon and nitrogen oxide emissions from two-stroke marine engines in 1996, with a 10-year compliance period, the boat manufacturers issued dire predictions of a slump in recreational boating and a huge loss of associated jobs.

In fact, two things happened: Two-stroke marine engines were saved with electronic fuel-injection, and four-stroke marine engines started to take over the market – the same four-stroke engines the manufacturers had said would be prohibitively expensive and too heavy for small boats.

Today, most new small boats have four-stroke engines. They are quieter, more fuel-efficient, less polluting and have added to the joy of boating. The weight and economic penalty, predicted by the anti-regulation boat manufacturers, turned out to be of no account. The problems were engineered out. That is what engineers do when they are unleashed: They design to meet the standards.

Similarly fleet-average standards, so hated by the automobile industry, have led to better cars, greater efficiencies, a reduction in air pollution and oil imports. They also pushed the industry to look beyond the internal combustion engine to such developments hybrids and all-electric vehicles and news concepts, such as hydrogen and compressed natural gas vehicles.

A high bar produces higher jumpers. Water restrictions have produced more efficient toilets, electric appliance ratings have reduced the consumption of electricity. Regulation is sometimes incentive by another name.

Well-thought out regulation is constructive, mindless regulation deleterious -- as when the purpose is political rather than practical. Restrictions on stem cell research and the unnecessary amount of ethanol added to gasoline come to mind.

In his energy executive order, repealing many of the Obama administration's clean energy regulations, Trump has done no one any favors: Less challenge, less innovation, less protection of the environment, and less global leadership is a cruel gift.

Take coal mining. Trump wants to save coal mining jobs, but his executive order will cause coal production to increase, further glutting the market. There are ways of burning coal more cleanly and if the president wants to help the coal industry, he should be supporting these. He also might want to look at the disposition of coal ash and its possible uses, not bankrupt what is left of the coal industry by false generosity.

Trump's energy executive order might have had virtue 40-plus years ago. Back in the bleak days of the 1973 Arab oil embargo, and the future shock it induced, coal was only plentiful energy source. I was one of the authors of a study, prepared for President Richard Nixon, that highlighted coal. Hence a passion that lasted through the Carter administration to gasify coal, liquefy it and back out oil with it whenever possible.

However the national genius produced a flood of innovation, leading today’s abundance of oil and gas.

The Trump administration is exhibiting a worrisome trend: fixing what is not broken, even if you have to break something to do it.

Llewellyn King, a frequent contributor to New England Diary, is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His e-mail is llewellynking1@gmail.com. This first ran on Inside Sources.

Tim Faulkner: Trump vs. the biosphere?

The day after Donald Trump’s surprise election win, the mood among environmentalists was, as expected, glum.

During his campaign, Trump, a climate-change denier and fossil-fuel proponent, vowed to withdraw from global climate treaties and neuter the Environmental Protection Agency. All told, his candidacy was considered a colossal threat to the biosphere.

Now that he’s two months away from taking office, it’s mostly guesswork as to which of Trump’s grand proclamations of environmental ruin will become reality.

Nationally, environmentalists expect that, at least, the goal of limiting temperature rise to 2 degrees is a lost cause, as is limiting atmospheric carbon dioxide to less than 400 parts per million.

To deal with their anxiety, environmental groups such as 350.org are encouraging environmentalists to partake in peaceful protesting. The National Resources Defense Council hosted a conference call for the aggrieved Nov. 10 titled “Defending Our Environment from the Trump Presidency.”

The consensus response from local government officials is to embrace autonomy.

“(Trump's win) puts an even greater burden on states to take action and be creative,” Rhode Island Gov. Gina Raimondo said during a Nov. 9 meeting of the Rhode Island climate council.

Raimondo received an update on Rhode Island’s long-term emissions-reduction plan. She and agency and department officials gave no indication of changing course on climate adaptation and mitigation efforts.

Raimondo said it's not known what Trump will do with President Obama’s Climate Action Plan. But Trump’s unexpected victory creates urgency to move forward with local initiatives, she added.

“Norms change in times of crisis, and I do believe we are facing a climate-change crisis, so we do have to get people to take action,” Raimondo said.

The governor confirmed that she isn't changing her neutral-to-favorable position on the proposed fossil-fuel power plant in Burrillville, a project that would be the state’s largest emitter of greenhouse gases.

Janet Coit, director of the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management, told ecoRI News that Trump’s victory was sobering. “It means we have to work all the harder.”

Fortunately, Rhode Island is surrounded by states with shared regional and local environmental goals, Coit said.

If federal support and guidance declines, she said, “Now we have to stop, regroup and guess that the leadership will have to come from the state level. I guess we have to look to ourselves more.”

Ken Payne, chair of state renewable energy committee, as well as food and farm programs, said the election means that progress on these issues will not only have to come from the state, but from communities and neighborhoods. Before the election, he and Brown University Prof. J. Timmons Roberts announced plans to launch a new, non-government affiliated group to advance green initiatives.

Roberts wasn't at the recent climate council meeting; he's in Morocco with students researching the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change negotiations.

In an article for Climate Home, he echoed the wait-and-see refrain put forth by environmental experts who wonder if the country and climate policy will be governed by Trump the negotiator or Trump the tyrant.

“So which Trump will govern? There is cause for both hope and fear,” Roberts wrote.

To others, fear caused by the election affirms reality. Morgan Victor of the Pawtucket-based environmental activist group The FANG Collective, said Trump’s win is evidence of American ongoing legacy of colonialism and slavery.

“It’s a reality that white supremacy runs in this country both overtly and covertly,” Victor said.

The Providence resident and member of the Wampanoag tribe participated in the ongoing Standing Rock Sioux pipeline protests taking place in North Dakota.

Having Trump in office will justify more attacks against indigenous groups and their land, Victor said.

“It’s scary. I hope it wakes people up, especially white people, to take care of the ones they love,” she said.

Tim Faulkner writes for ecoRI News.

How eco-friendly is your pet?

Tanner, the ecoRI News newshound.

-- Joanna Detz/ecoRI News

By DONNA DeFORBES, for ecoRI News

Pets are beneficial to our health and make wonderful family companions, but have you ever considered how they add to your carbon footprint? Can a pet be eco-friendly?

Dogs A controversial 2009 book claimed that owning a dog is twice as ecologically harmful as driving an SUV — the main reason being the large amount of land and energy given over to producing their meat-based food.

Research estimates that 1.7 miles of land is needed to cultivate 2.2 pounds of chicken — beef is higher, of course. That doesn’t sound too bad until you know that the average dog consumes about 360 pounds of meat annually, and that there are upwards of 83 million owned dogs in the United States.

Eco option: Feed your dog food comprised of chicken or rabbit, instead of beef or lamb, to reduce his dietary footprint. Or try a vegetarian dog food.

Then there’s the disposal of all that poop — about 274 pounds per dog per year, according to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Unscooped poop contains nutrients that contaminate local waters and deplete the oxygen supply, which is vital to seagrass, fish and other marine creatures. There are up to 65 diseases including e. coli, roundworms, giardia and salmonella that can be transmitted through dog feces to other dogs, cats or people.

Dog poop, even when scooped and tossed in the trash, produces methane, a greenhouse gas stronger than carbon dioxide.

Eco option: The Natural Resources Conservation Service offers ideas on how to properly compost dog wasteso that it can be used later as a quality soil additive.

Cats The nation’s 95 million cats annually generate 2 million tons of litter. That litter is usually the non-biodegradable, clay-based kind that can only be produced by strip mining the earth.

Cat poop can be equally destructive, since cats are often the carrier of the parasite, Toxoplasma gondii, an organism that kills sea otters and other creatures when people wrongly flush cat poop down the toilet. T. gondii also affects humans, especially pregnant women and those with weakened immune systems.

Eco option: Choose an eco-friendly litter made from recycled newspaper, wood shavings, sawdust or corn cobs. Toss into the trash, not the toilet.

Cats also get a bad rap for their penchant for killing wildlife. According to one scientific report, U.S. domestic cats kill an average of 12.3 billion mammals and 2.4 billion birds annually. Feral and outdoor cats also urinate and poop in other people’s yards and gardens, potentially infecting the soil and children’s play areas.

Eco option: Protect your local ecosystem by keeping your cat indoors.

What you can do All is not lost for dog and cat lovers. You can reduce your pet’s footprint by buying eco-friendly pet supplies when possible. You can find beds, collars, leashes and toys made from organic fabrics or recycled materials. Choose biodegradable poop bags and eco-friendly litter, and opt for pet shampoos free of sodium lauryl sulfate, and flea and tick solutions that use essential oils.

Consider the rabbit If you’d love a pet, but are concerned about their eco footprint, there is one house pet that ranks pretty high on the scale of greenness: the bunny rabbit. Here’s why:

Since bunnies are vegetarians, eating a variety of greens and herbs, you can grow their food alongside yours in a lovely garden. They can also weed your lawn, as rabbits love dandelions.

Rather then contaminate the waterways, rabbit poop acts as the perfect garden fertilizer. You can dump it directly onto your flowers or mix it into your compost pile.

Shredded newspaper, hay or straw makes the perfect litter box filler, and you can toss all of it into the compost right along with the bunny poop.

A rabbit’s favorite toys are things you’d often toss or recycle — cardboard toilet paper tubes, boxes, wood scraps. Rabbits actually need to chew on such things to manage their continuously growing teeth.

If this information inspires you to adopt a house rabbit, get informed first. Bunnies tend to have a disposable reputation, but while their 8-10 year lifespan is not as long as cats' or dogs', it does require a long-term commitment.

Rhode Island resident Donna DeForbes is the founder of Eco-Mothering.com, a blog that explores ways to make going green fun and easy for the whole family. She is a contributor to Earth911, MammaBaby and author of the e-bookThe Guilt-Free Guide to Greening Your Holidays.

Frank Carini: Dog-poop pollution in the Westport River

WESTPORT, Mass.

Unlike many New England rivers, the one that shares a name with this popular summer town doesn’t have a legacy of industrial pollution buried in its sediment. But despite not being polluted with toxins from long-since-gone jewelry makers and dye manufacturers, the Westport River and its watershed still face the threat of contamination from stormwater runoff, nitrogen-rich fertilizers, failing septic systems and outdated cesspools.

In fact, one of the more commonly seen but often ignored threats — unless you happen to step in it — to this two-pronged river and its economically vital watershed is waste left on the ground by inconsiderate pet owners. While certainly not on the order of concern of, say, carbon pollution, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) does label dog waste a “pollutant.”

Sorry, Snoopy, but dog poop is 57 percent more toxic than human waste, according to the EPA, and can harbor bacteria and parasites that cause illness in humans.

This waste problem is so rampant in dog-friendly Westport and the surrounding area that the Westport River Watershed Alliance (WRWA), the nonprofit protector of the this important natural resource, was compelled this year to print a two-fold brochure entitled “The Shocking Truth About Your Dog’s Poop.”

“Even the smallest amount of dog poop is filled with bacteria,” said Roberta Carvalho, the WRWA’s science director.

It has been estimated that an ounce of dog waste can contain 650 million fecal coliform bacteria. The EPA has estimated that two to three days’ worth of dog poop from a neighborhood with about a hundred dogs would contribute enough bacteria to temporarily close a bay, and all watersheds within 20 miles of it, to swimming and shellfishing.

In 1976, the Westport River Defense Fund was created in opposition to a septage lagoon proposed by the Board of Health that would have been built near the East Branch of this tidal river. The idea to construct a sewage pit by the river to dispose of the town’s septage pump-outs created a major controversy, and resulted in what is now the WRWA.

“It didn’t happen,” Carvalho said. “It was our first victory.”

Since that battle nearly four decades ago, the Alliance has grown from 15 members to more than 2,000. Numerous projects have been developed over the years that promote education and advocacy — all in an effort to protect one of the region’s most significant coastal assets in both habitat quality and scenic beauty.

But the fact that 23 percent of shellfish beds in the Westport River are permanently closed for harvesting documents the continued problem of contamination, according to Carvalho.

In all, some 50 percent of the river’s total shellfish beds are seasonally or conditionally closed, and 76 percent of the river’s harvest potential is limited because of bacterial pollution, according to the WRWA..

“The river has gotten much better in the past 10 years, but nitrogen pollution, runoff and septic systems are still a concern,” said Carvalho, who has been with the organization for 13 years. “It’s a costly endeavor, but it is vital we protect our water resources.”

Nutrient loading and pathogen contamination are water-quality concerns, particularly in the upper reaches of the river’s 35-mile shoreline. The river suffers from the problem of eutrophication, especially in the upper East Branch. Carvalho also is concerned about the emerging threat of chemicals from personal-care products and pharmaceuticals. In addition, she believes Massachusetts needs to do a better job phasing out antiquated cesspools and replacing them with modern septic systems or municipal sewer. Westport, for one, doesn’t have public sewer.

WRWA staffers work with local schools to educate students, from kindergarten through high school, about the importance of protecting the watershed, and the organization has partnered with municipal and state agencies to run water-quality programs. The nonprofit also promotes the use of buffer strips, rain gardens and low-impact development technologies to help keep the river and its watershed clean.

WRWA has maintained a summer bacteria-monitoring program for the Westport River since 1991, and the organization’s collection and analysis of site samples has been used by municipal and state agencies to document bacterial contamination.

The Westport River watershed spans two states, Massachusetts and Rhode Island.The watershed

The Westport River has two branches. The smaller West Branch is about 7 miles long, rising from a confluence of brooks near the village of Adamsville, R.I. The West Branch separates the village of Acoaxet from the rest of Westport — one needs to pass through Rhode Island to reach the rest of the town.

The larger East Branch is about 11.5 miles long, rising at the border of Westport and Dartmouth, at Lake Noquochoke. After a short length, the river meets Bread and Cheese Brook before reaching the head of Westport village, where the WRWA will soon move into its new home. From there, the river continues southward, fed by several brooks, before an initial widening to between 100 and 400 yards at Widows Point.

Once in Westport Harbor, the combined branches bend around Horseneck Point, before flowing into Rhode Island Sound, just west of Horseneck Beach State Reservation, at the point where Rhode Island Sound meets Buzzards Bay.

The Westport River watershed encompasses parts of Westport, Dartmouth, Fall River and Freetown, and Tiverton and Little Compton in R.I., and 85 percent of the watershed’s landmass drains into the river’s two branches.

Frank Carini is editor of ecoRI News, where this piece originated.

Llewellyn King: Happy days for U.S. energy consumers

There is something extraordinary happening on Main Street, in the suburban strips, and at country stores: Workers are lowering the prices on the signs for gasoline. Veterans of the energy crisis that began in 1973 and has continued, with perturbations, ever since, are trying to get their heads around this enormous reversal of fortune: there is no energy crisis for any fuel in the United States as winter approaches.

That was the message delivered loud and clear at the annual Energy Supply Forum of the United States Energy Association (USEA). Indeed the main problem, if there is one, is that oversupply is driving down some fuel prices, like for oil and natural gas, which could result in higher prices later as producers curb production.

"Who would have believed it?" asked Barry Worthington, president of USEA. This year the forum, which has been known to be filled with alarm and foreboding predictions, was full of robust confidence that the nation will breeze through the coming winter, and that consumers will pay less to stay cozy than they have for several winters — but especially the last one.

Stocks of gas and oil are plentiful. It is not just that heating oil will be cheaper, nature will also play a part: the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration predicts a mild winter. No one is expecting a repeat of last winter's "Polar Vortex," which brought some big utilities close to being unable to meet customer demand in the extreme cold.

Mark McCullough, executive vice president for generating at American Electric Power (AEP), which serves customers in 11 states, described how the giant utility came close to the edge. This winter, McCullough thinks, things will be fine. But he is less sanguine about the future of AEP and its ability to deliver electricity in 2016 and beyond, if the Environmental Protection Agency holds firm on its proposed rule to curb carbon emissions from coal-fired plants.

AEP, which straddles the Midwest, has the largest coal-fired fleet in the country. McCullough said that his company had just come off extensive efforts with the so-called mercury rule and now was plunged into a very difficult situation. McCullough was joined by oil producers and refiners in worrying about another proposed rule from the EPA on ozone. Neither the utilities nor the oil producers and refiners feel that the EPA's proposed ozone regulation can be met.

In short, in a buoyant energy world, there are clouds forming. But unlike the last 41 years, these clouds are regulatory rather than resource-generated; public policy in their origin, rather than in the scheming of foreign oil cartels. Indeed, Robert Strout of BP confidently predicted that in a little more than 20 years, the United States could be energy self-sufficient.

The other problem going forward, in the new time of bounty, is energy infrastructure. The industry needs more pipelines to facilitate the shift from coal to gas; better infrastructure to get the new oil to the right refiners. (Refiners actually favor moving oil by train as well as by pipeline.)

USEA's Worthington, a veteran of energy crises of the past, said ruefully the other thing that might happen is that excessive domestic production and falling prices will lead to a period when producers will stall new production and prices will rise. "Markets do work," he said, commenting on the cycles of the hydrocarbon market.

For now, with international economic activity waning, and hydraulic fracking unlocking oil and gas at an astounding rate, this is a bonus time for the American consumer. For people like myself, who have spent more than 40 years commenting and reporting on the bleak energy future, this is indeed a time of astonishment. We had heard predictions of doom if China industrialized, expectations of steadily declining U.S. production, and more and more of our wealth being exported to buy energy.

Now, if Congress acts, we will be a serious exporter. This winter of our discontent is made glorious summer by fracking, as Richard III did not quite say. Astonishing!

Llewellyn King (lking@kingpublishing.com) is host and executive producer of "White House Chronicle'' on PBS and a longtime publisher, editor, writer and international business consultant.

Warm-blooded gun

Photo by JAMES J. ORAM, a Connecticut-based photographer specializing in black-and-white images that evoke a lot of moods, although chiefly something between mellowness and melancholy.

The possession of pit bulls in tough neighborhoods suggests that they're meant as signs of strength and protection -- a sort of warm-blooded gun. Mr. Oram has had much opportunity to see pit bulls in some of the gritty old factory towns of the Naugatuck River Valley, where he lives.

The Naugatuck, by the way, used to sport a variety of vivid colors from the industrial wastes of varying toxicity that were directly dumped into the river before the arrival of the Environmental Protection Agency. The pollutants would then flow down into Long Island Sound, where they would help kill fish and birds that they hadn't already been killed upriver.

Mr. Oram's Web site is here.