Good news for GE and New England

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Here’s another example of how offshore wind power can be an economic boon for New England:

Vineyard Wind LLC has picked Boston-based General Electric to provide the turbines for its project south of Martha’s Vineyard – in what will be the first large-scale offshore wind farm in the United States. European nations are far ahead of us!

The wind-farm developer, a joint venture owned by Avangrid and Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners, had originally planned to put up turbines made by the Danish-Japanese venture MHI Vestas (soon to be entirely Danish).

But permitting delays led Vineyard Wind to change the wind farm’s layout and equipment. So there will be 62 GE turbines instead of the 84 planned with MHI Vestas. But those General Electric turbines are the world’s most powerful. It’s nice to think that a Massachusetts company will provide this gear for this massive New England project.

And the news may suggest a brighter future for GE, which has faced hard times the past few years.

Hint this link for more information.

Actually, GE's lights are still on

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Lights Out: Pride, Delusion, and the Fall of General Electric, by Thomas Gryta and Ted Mann, memorably describes how one of America’s oldest, biggest and most celebrated companies started taking wrong turns under its charismatic (and probably over-rated) CEO Jack Welch and his successor, Jeff Immelt, and ended up much less profitable, smaller and weaker.

This is superb corporate history, with the right mix of historical context and big picture stuff and anecdotes that add spice to the tale of very smart, but sometimes very wrongheaded and arrogant, execs making disastrous mistakes as well as, to be fair, achieving some surprising successes. Overpriced acquisitions and mountains of debt played a big role in the burgeoning woes of the conglomerate, along with dubious creative accounting, which some have alleged verged on fraud.

It’s a sort of a mystery story: How could such a huge and diversified company get into such trouble?

By the way, from all the negative news about GE in the investment community in the past couple of years you might not remember that it remains a very big company. Last year, GE was ranked among the Fortune 500 as America’s 21st-largest firm as measured by gross revenue.

New Englanders in particular will want to read about the very human reasons that the company moved its headquarters to Boston after many years in Fairfield, Conn.

GE looking better, but Boeing....

Carmen Miranda in a 1945 advertisement for a General Electric FM radio in The Saturday Evening Post

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

After many cheers when giant General Electric company decided to move its headquarters to Boston from Fairfield, Conn., the noise turned to boos as its stock price tanked. But last year, the stock of the venerable company surged 53 percent from 2018, its biggest jump since the 1980s, and much better than the nearly 30 percent increase in the Standard & Poor’s 500 index, notes The Boston Globe’s estimable Jon Chesto.

Much of the turnaround has been attributed to new CEO Larry Culp’s rigorous and decisive management.

Still, there might be a big problem this year as GE waits to see if engine orders pick up for Boeing’s 737 Max jetliners, grounded last year after two crashes that killed hundreds of people. The engines were not a factor in the crashes.

In any event, the Boston area should still be happy that a company with such engineering expertise as General Electric is based in Boston – a world-renowned center for science and engineering. Synergy! And investors should always keep in mind how fast things can change even for the biggest companies.

A week is an eternity in business….

Meanwhile, haggling continues on what sort of building should go on the site of what was to have been GE’s headquarters in Boston’s Seaport District. The company had planned to put up a sort of sci-fi 12-story headquarters building but decided to settle for two rehabbed older buildings next door – a touch of New England conservatism.

To read Mr. Chesto’s piece, please hit this link.

Partners and GE team up in AI project

The word "robot" was coined by Karel Čapek in his 1921 play R.U.R., the title standing for "Rossum's Universal Robots"

The road to artificial intelligence: This ontology represents knowledge as a set of concepts within a domain and the relationships between those concepts.

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

“Partners HealthCare and General Electric, both based in Boston, have announced that they are in the midst of obtaining FDA approval for deployment of their newly developed artificial intelligence (AI) to hospitals and health systems across the world. Partners and GE Healthcare have been partnering to develop the AI program for nearly three years.

“As a baseline, the health-care providers’ new platform seeks to couple data results from GE imaging equipment with electronic medical record inputs, and then use the AI to aid clinicians in making treatment decisions. The new technology’s approach differs from less accurate and overreaching ones currently on the market, using contextual data from imaging equipment and aiming to help clinicians make decisions, rather than making the decisions for them. In addition, the AI and its data would be a shared platform, allowing the system to improve itself by exploring a wider range of information. The software’s design gives all clinicians navigable access to patients’ medical records that can be utilized and acted upon in the midst of day-to-day work.

“‘What we are doing now is we’re actually taking the capabilities of these platforms, and you’re going to expose these to the external world, from our developer community perspective so that you know developers across the globe could use some of these features, and that cross-section that we have created, to rapidly develop applications,’ said Amit Phadnis, chief digital officer for GE Healthcare.’’

Don't depend on one company; mill village in verse

Cleanup activity at one of the General Electric Pittsfield plant Superfund sites on the Housatonic River, which the company heavily polluted in its heyday.

One thing that any community —in New England or elsewhere — should avoid is over-reliance on one or two big companies. Pittsfield, Mass., found that out when General Electric, which once employed 14,000 people at its facilities in that little city, closed most of its operations there, leaving economic devastation. Now, Pittsfield (the capital of the Berkshires) seeks a diverse collection of much smaller firms and is having modest success in turning around the city.

Jonathan Butler, the president and CEO of 1Berkshire, a business development group, told New England Public Radio:

“If we were to have another employer with 10,000 or 15,000 jobs come in, {to Pittsfield} that would scare me. I think that would scare those of us [who] work in economic development.”

I have strong memories of covering the 1970 elections in Pittsfield for the old Boston Herald Traveler. It then still had a thriving downtown, though you could sense slippage.

To read more, please hit this link.

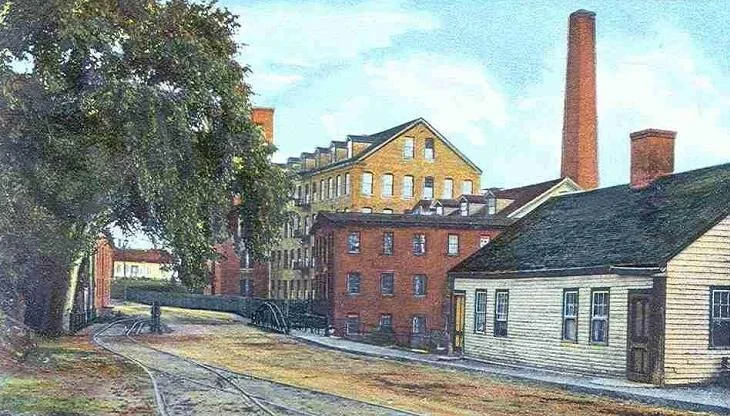

Assawaga Mill, Dayville, Conn., in 1909

Factory Town in Verse

Old New England mills (many of them beautiful, and built for the ages) and the towns that grew around them have become the subjects of a curious form of romance in recent years. So now we have poet, novelist, essayist, environmentalist and former Connecticut deputy environmental commissioner David K. Leff out with a verse novel, The Breach: Voices Haunting a New England Mill Town, which studies the decline of such a community facing economic and an environmental crises.

To hear Mr. Leff talk about his book, and read from it, please hit this link.

A corporate move that worked for a state

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Massachusetts is making back the $87 million that it spent on Boston property connected with General Electric’s headquarters move there – plus $11 million in profit, helped by the city’s booming economy. (GE, however, has not been booming.) Also, the company has not taken the $25 million in tax breaks offered by Boston. GE will remain in the Seaport District, but with a considerably smaller footprint than foreseen when the company decided to move its headquarters from Connecticut.

So some government incentives to lure companies work out okay. That especially when you’ve got a highly competent governor such as Bay State Republican Gov. Charlie Baker and Boston’s able Democratic Mayor Marty Walsh who craft careful offers to protect taxpayers

Llewellyn King: The case against mega-mergers is written in U.S. history

A judge has green-lighted the $85 billion merger of Time Warner and AT&T. Unless the Trump administration appeals and wins on appeal, another behemoth will take the field.

This merger, it is assumed, will lead to a flurry of other mergers in communications. Witness Comcast’s $65 billion bid for Fox, topping Disney’s $52.4 billion offer.

This is heady stuff. The money on the table is enormous, in some cases dwarfing the economies of small countries.

Merging is an industry unto itself. A lot of people get very rich: They are investment bankers, arbitragers, lawyers, economists, accountants, publicists and opinion researchers. When really big money moves, some of it falls off the table into the willing hands of those who have managed the movement.

The fate of the real owners of these companies, the stockholders, is more doubtful after the initial run-up. The earlier merger of Time with Warner Communications is considered to have been disadvantageous for stockholders.

Another concern is the mediocre performance of conglomerates. The latest to have run into trouble is General Electric, which had managed to do well in many businesses until recently.

A more cautionary story is what happened to Westinghouse when it went whole hog into broadcasting and lost its footing in the electric generation businesses. This was spun off, sold to British Nuclear Fuels in 1997, then sold again to Toshiba and later went into bankruptcy.

From the 1950s, Westinghouse it bought and sold companies at a furious rate, until the core company itself was sold in favor of broadcasting. One of Westinghouse’s most successful chairmen, Bob Kirby, told me it was easier for him to buy or sell a company than to make a small internal decision.

In another pure financial play, a group of hedge funds bought Toys R Us and with the added debt, it failed.

In many things, big is essential in today’s economy. News organizations need substantial financial strength to be able to do the job. Witness the cost of covering the Quebec and Singapore summits. As Westinghouse proved by default, big construction needs big resources. That is indisputable.

When growth through acquisition becomes the modus operandi of a company, something has gone very wrong. The losers are the public and the customers. The new AT&T, if it comes about, will still need you and I to lift the receiver, watch its videos and subscribe to its bundles.

Recently, I was discussing the problems customers have with behemoth corporations on SiriusXM Radio's "The Morning Briefing with Tim Farley" when a listener tweeted that I hated big companies and their CEOs and loved big government.

Actually, I’d just spent a week with the CEOs of several companies, admirable people, and I don’t think government should be any bigger than needs be. I certainly don’t think government should perform functions that can be better performed in the private sector.

The problem is size itself.

When any organization gets too big, it begins to get muscle-bound, self-regarding. Although it might’ve been built on daring innovation, as many firms have been, supersized companies have difficulty in allowing new thinking, reacting nimbly and adopting innovative technologies and materials.

If large corporate entities were as nimble as small ones, the automobile companies would’ve become the airplane manufacturers in the 1920s and 1930s. They had the money, the manufacturing know-how and the engineering talent. They lacked the vision. It was easier to be rent-takers in the production and sale of automobiles.

Likewise, it’s incredible that FedEx was able to conquer the delivery business when another delivery system, Western Union, was up and running. But Western Union was big, smug and monopolistic. They had the resources and an army of staff delivering telegrams.

Companies like Alphabet (Google’s owner) snap up start-ups as soon as they are proven. That snuffs out the creativity early, even if it wasn’t meant to, and makes Google even more dominant. I would argue too big for its own good -- and for ours.

Llewellyn King (llewellynking1@gmail.com) is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He is based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

The epicenter of merger mania -- Wall Street, with the New York Stock Exchange draped with the flag.

Now it's Apple's turn to ask localities for a huge handout

Apple headquarters in Cupertino, Calif., in Silicon Valley.

Adapted From Robert Whitcomb's "Digital Diary,'' in GoLocal24.com

Apple says it plans to build another corporate campus. It also says it will hire another 20,000 workers, in part because of the new U.S. tax law, which cuts corporate income taxes. (Not all of the windfall will go to investors in the form of stock buybacks and dividend increases!)_

Of course, Apple’s announcement means that various cities and states around America are already looking into how they can bribe the Cupertino, Calif., company to build its new campus in their jurisdiction. Presumably vast tax breaks, to be subsidized by the individuals and businesses already there, will be offered, along with very expensive physical-infrastructure improvements. As with Amazon, Greater Boston (which you might say now sort of includes northern Rhode Island) would be in the running because of the huge technology complex there. But would such legal bribery be worth it for the macro-economy of Greater Boston?

Local politicians’ and some business leaders’ obsession with luring huge, rich, sexy tech companies may be popular in the short term but the diversion of so many public resources to a few extremely profitable big companies could have a very big long-term cost. The problems of General Electric that were revealed after it was lured to set up its headquarters in Boston provide a useful caution sign.

Chris Powell: Conn. shouldn't get emotional about exit of GE and Aetna

The soon-to-be former headquarters of Aetna in Hartford. It looks like a hotel or part of a college.

Having spent the last several decades capitulating to its government and welfare classes and squandering its advantages over other states, Connecticut has a lot to apologize for and correct. But it shouldn't feel quite so bad about the departure of General Electric's headquarters from Fairfield to Boston and the departure of Aetna's headquarters from Hartford to New York.

People have thought of GE and Aetna as Connecticut companies when they really haven't been.

General Electric got started in Schenectady in upstate New York, consolidated in New York City, and acquired many related companies around America before moving its corporate headquarters to Fairfield and transforming itself into an international financial conglomerate.

While Aetna started in Hartford in 1853, as it grew it also opened offices throughout the country and the world and became a financial conglomerate much like GE. Aetna has 5,000 employees in Connecticut but 44,000 elsewhere.

The boards of both companies long have lacked members with roots in the state.

People here like to think of United Technologies Corp. as a Connecticut company as well. But while UTC began in Connecticut with Pratt & Whitney Aircraft and retains its headquarters here, like GE and Aetna the company used its earnings to acquire other businesses and became an international conglomerate. UTC's employment in the state has declined steadily as it has expanded its aircraft engine and other businesses elsewhere.

Since the businesses of these companies are so dependent on and/or or regulated by national governments, politics has required them to diversify their geography. It's not enough for them to have the support of Connecticut's delegation in Congress. They need support nationally.

Meanwhile other national and international companies have expanded into Connecticut for the same reason, perhaps causing emotional pangs and resentments in the places where they originated.

But that's the evolution of most big businesses -- from entities with local character and geographic loyalty to cold accumulations of mobile capital. They're not emotional about Connecticut and the state is silly to be emotional about them.:

Defending their ratification of the new state employee union contract, Democratic state legislators say that its 10-year term, criticized by Republican legislators as too long, is no big deal. The Democrats note that state employee union contracts have been reopened early before, as the one just extended was.

But that argument is weak, since reopening such contracts is possible only with the consent of the unions and there is no guarantee that the unions will give their consent. Indeed, if, as the Democratic legislators suggest, reopening contracts is a mere technicality, why should their length be specified at all? Why shouldn't the contracts be written so they can be terminated by either party at any time?

When union leaders urged their members to ratify the new contract, they did not argue, as Democratic legislators argue now, that the duration clause is meaningless. No, union leaders argued that the contract provides long-term protection of jobs and compensation. Union members might not have ratified the contract if its four-year guarantee of employment really meant that layoffs could begin at any time.

The essence of the contract issue remains that Democrats, the party of government employees, believe that government employees should have more power over the government than the voters do. It's nonsense but it is repaid well by government employees at election time.

Chris Powell is managing editor of the Journal Inquirer in Manchester, Conn.

Connecticut needs to fix its cities

Aetna's headquarters in Hartford, but not for long: The company is moving its home office to Manhattan.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb's "Digital Diary,'' in GoLocal24.com:

Derek Thompson, writing in The Atlantic’s online service, has some interesting takes on Connecticut’s current fiscal problems. The state government has a huge deficit, some cities are effectively bankrupt, taxes are amongst the highest in the nation and some big companies have fled. And yet the state remains the richest on a per-capita basis in America, albeit largely because of New York City-connected rich folks living in Fairfield County. (Massachusetts is the second-richest; New Jersey the third.)

He notes some remarkably little reported reasons for the state’s ills: One is that Connecticut, like America in general, has lost much of its high-valued manufacturing, a sector for which Connecticut was once famed around the world. (I lived near Waterbury for four years in the early and mid-‘60s, from when I well remember the busy factories up and down the colorfully polluted Naugatuck River.)

Very highly paid people in finance, many of them commuting to Manhattan but many doing their thing in Stamford and Greenwich, have offset some of this loss. However, finance, which of course follows the ups and downs of Wall Street, is more cyclical than manufacturing. And the latter provided a wider range of well-paying jobs to many more people than does finance.

Another important change that Mr. Thompson cited is that the big cities close to Connecticut --- especially New York and Boston – have become much safer and more attractive. Rich people and Millennials have been moving back into them, having grown bored with suburbs, even those as attractively sylvan as some on Connecticut’s strip of the Long Island Sound shoreline.

Conservatives who seem obsessed with high taxes above all else should note that some of the big companies pulling their headquarters from Connecticut are not exactly moving to low-tax venues. Consider that Aetna is leaving Hartford for Manhattan and General Electric has left Fairfield for Boston. They want the dynamism of those cities and are happy to pay for it.

The Nutmeg State has poor, high-crime and often badly run cities. If the state is to improve its long-term prospects, I and Mr. Thompson would agree, it needs to fix its cities. Hartford, which used to be a vibrant and mostly middle-class city before bad municipal government, ill-considered“ urban renewal’’ and other factors drove it into the ditch, is expected to go into official bankruptcy soon. That should let it start cleaning up its act and make it a place that people, especially young adults who might otherwise go to New York, would want to live and work in. That could help turn around the whole state. After all, Hartford is the state capital.

General Electric's impact on Massachusetts

This from the New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com):

"New England Council member General Electric (GE) recently released an economic impact analysis (EIA) of the company’s operations in Massachusetts.

"The report, 'General Electric’s Impact on the Commonwealth of Massachusetts’s Economy,' was conducted by Frost & Sullivan, a business economic intelligence and research company, and breaks down GE’s impact into five categories: total economic impact, employment, labor compensation, charitable impact, and investment. GE contributed $6.31 billion to the Massachusetts economy in 2016 through the company’s total production output in the state. GE’s operations in Massachusetts support 17,829 jobs; 4,750 of which come from GE, 4,921 come from supply chain partners, and 8,158 supported by the spending by GE employee households. These direct, indirect, and induced jobs generated $2.352 billion in labor compensation in 2016 due to GE’s presence in Massachusetts. The analysis also found that GE donated $13.26 million in charitable contributions while GE employees volunteered over 6,650 hours to charities in Massachusetts. The total impacts also do not include investments GE has made in the state for future operations, including the company’s headquarters relocation to Boston and the opening of GE Healthcare’s new Life Science headquarters in Marlborough.

"The New England Council thanks GE for its continued investment in Massachusetts and the entire New England region, which contributes to the strengthening of the region’s economy and provides jobs to thousands of New England residents.''

Sam Pizzigati: Other than making mountains of money for themselves, what do America's CEOs make these days?

Via OtherWords.org

Jeff Immelt, the CEO of General Electric since 2001, is retiring. The 61-year-old will be making a well-compensated exit.

Fortune magazine estimates that Immelt will walk off with nearly $211 million, on top of his regular annual pay. Immelt’s annual pay hasn’t been too shabby either. He pulled down $21.3 million last year, after $37.25 million in 2014.

But Immelt’s millions don’t come close to matching the haul that his immediate predecessor, Jack Welch, collected. Welch’s annual compensation topped $144 million in 2000. He stepped down the next year with a retirement package valued at $417 million.

What did Immelt and Welch actually do to merit their super-sized rewards? What did they add to a GE hall of fame that already included such breakthroughs as the first high-altitude jet engine (1949) and the first laser lights (1962)?

In simple truth, not much at all.

“We bring good things to life,” the GE ad slogan used to proudly pronounce. Not lately.

And not surprisingly either. Mature business enterprises, we’ve learned over recent decades, either make breakthroughs for consumers or grand fortunes for their top execs. They don’t do both.

Why not? Making breakthroughs, for starters, takes time. Enterprises have to invest in research, training, and nurturing high-performance teams.

Years can go by before any of these investments bear fruit. By that time, the executives who made the original investments might not even be around.

Grand fortunes, by contrast, can come quick. CEOs can downsize here, cut a merger there, then sit back and watch short-term quarterly earnings — and the value of their stock options — soar.

If those don’t do the trick, CEOs can always just slash worker pensions or R&D and put the resulting “savings” into dividends and “buybacks,” two slick corporate maneuvers that jack up company share prices and inflate executive paychecks.

On any CEO slickness scale, Jack Welch would have to rank right near the top. In 1981, his first year as the GE chief, Welch quickly realized he was never going to get fabulously rich making toasters and irons.

So Welch started selling off GE’s manufacturing assets. In his first two years, analyst Jeff Madrick notes, Welch “gutted or sold” businesses that employed 20 percent of GE’s workforce.

By 2000, Welch himself was making about 3,500 times the income of a typical American family.

By contrast, in 1975, Welch’s predecessor, Reginald Jones, took home merely 36 times that year’s typical American family.

As Welch’s successor, Jeffrey Immelt would give an apology of sorts in a 2009 address at West Point. Corporate America, he told the corps of cadets, had wrongfully “tilted toward the quicker profits of financial services” at the expense of manufacturing and R&D, leaving America’s poorest 25 percent “poorer than they were 25 years ago.”

“Rewards became perverted,” Immelt went on. “The richest people made the most mistakes with the least accountability.”

Unfortunately, and sadly, Immelt never took his own analysis to heart. As a rich CEO in his own right, he continued to make mistakes and suffer no particular consequences.

One example: After the Great Recession, Immelt froze the GE worker pension system and offered workers a riskier, less generous 401(k). Within five years, notes the Institute for Policy Studies, the GE pension deficit widened from $18 billion to $23 billion — even as Immelt’s personal GE retirement assets were nearly doubling to $92 million.

“If we want to slow — or better yet, reverse — accelerating income inequality,” the Harvard business historian Nancy Koehn noted a few years ago, “the most powerful lever we have to pull is that of outrageous executive compensation.”

How many more outrageously compensated executives will retire off into lush sunsets, the Jeff Immelt story virtually begs us to ask, before we start yanking that lever?

Sam Pizzigati, an Institute for Policy Studies associate fellow, co-edits Inequality.org. His latest book is The Rich Don’t Always Win.

How much can governors really help their states' economies?

From Robert Whitcomb's "Digital Diary'' column in GoLocal24.com

Rhode Island Gov. Gina Raimondo was understandably pleased when the state’s unemployment rate fell below the national average in January, to 4.7 percent, for the first time in almost 12 years. Meanwhile, some high-profile companies have moved to the state or expanded there and there’s quite a lot of newconstruction underway. To me, the best news has been that the big projects at the Route 195 relocation land are starting to get cooking and that rapidly growingUnited NaturalFoods Inc. is now based in Providence.

How much of this was due to Ms. Raimondo’s leadership? Economics has so many variables that it’s hard to say. For that matter, the Ocean State is so tiny it’s hard to say that there’s a “Rhode Island economy.’’ It’s part of the much bigger regional, national and international economies. And note that a shrinking state work force explains at least some of the recent jobless-rate drops.

I would say, however, that Ms. Raimondo’s knowledge of business and national connections as a former venture capitalist, her willingness to implement long-overdue reforms and her calm and intelligence have indeed inspired confidence in firms that might be candidates for moving to or expanding in the state. That she’s willing to get very able people from outside the state with fresh perspectives to join her administration rather than automatically pick well-connected Rhode Islanders (“I know aguy…’’) has also been good, although it has, along with her fancy education, gotten her labeled an “elitist,’’ which I don’t believe this daughter of middle-class Rhode Islanders considers herself. The more new people moving into Rhode Island the better, to dilute the parochialism that is at the root of many of its political and economic problems.

As in many states, her administration has had headaches with big computer systems (e.g., public benefits and the Division of Motor Vehicles). Could she have headed these headaches off by firing people faster who were charged with getting them going but didn’t succeed? Probably.

Hire Republican Ken Block, a brilliant systems guy, to oversee state computer systems? That would be exciting.

Ms. Raimondo has gotten a lot of flak from some people about what former Gov. Lincoln Chafee calls the “candy store’’ approach of using tax incentives to lure businesses. I share a lot of this dislike. It can create a race to the bottom as states compete to get sexy companies. As I’ve written here before, for long-term economic success, jurisdictions must focus on broad improvements, especially in education and infrastructure. The governor says she is focusing on those things but the $130 million in tax incentives so far in her term understandably get a lot of attention. And how do you make these companies stay?

Pretty much every state and large city play the tax-incentive game in varying degrees.

Of course, the governor thinks that attracting such big companiesas General Electric to set up new operations in the state signals to other companies that it’s now a good place to do business and, they find, a beautiful place to live for many.

She has had some success in changing the perception of out-of-staters about the Ocean State so that many have come to believe that the Rhode Island is finally, if slowly, fixing its business climate. The deeply embedded tribalism, negativity and cynicism in the state militate against her but I believe she’s making progress – two steps ahead, one step back.

Meanwhile, I’m sure that Rhode Islanders would like to see a updated list of companies that have decided to stay and grow in the state as a result of Raimondo administration policies.

On two big issues she’s been embroiled in: the car tax, about which she is less enthusiastic about cutting than some other politicians, and “free college’’ for two years:

Cutting or eliminating the car tax, as hated as it is, will have little or no effect on the state’s economy. And rather than “free college,’’ it might make far more sense to put some of the tax revenue to be spent on subsidizing students into creating a public-private vocational education system (including apprenticeships) like that which has been so successful in Germany. And even more important is pushing asideRhode Island special interests in order to adopt a K-12 public-education system with the rigor of Massachusetts’s, which has helped make the Bay State so prosperous in the past couple of decades.

Ian Morrison: Sacred Heart University buying Boston-based GE's former headquarters in Conn.

Part of the former GE complex in Fairfield.

Sacred Heart University (SHU) has purchased General Electric’s (GE’s) former global headquarters site in Fairfield, Conn. This 66-acre parcel will become an extension of SHU’s nearby main campus, as well as its Stamford Graduate Center. The acquisition is a strategic and practical move for the university, which has needed room to expand several existing programs and campus facilities, in conjunction with new building and renovation work.

The GE site, which SHU will call its West Campus, includes 550,000 square feet of existing building space for current and future use and 800 above-ground and underground parking spaces. The West Campus is expected to attract more than 250 new students and expand faculty and facilities staffing requirements by at least 50 people.

The relocation of GE’s corporate headquarters to Boston was seen as a significant blow to Fairfield’s economy and to the state. GE was Fairfield’s largest taxpayer, and many of its executives and staff resided locally. Not all of the GE employees who worked in Fairfield were forced to move, though; several hundred transferred to the company’s facilities in nearby Norwalk, Conn. Still, GE's departure left a void in support for local nonprofit organizations.

In announcing its reasons for leaving, GE cited the lack of innovation and incubation opportunities in Connecticut and noted the presence of dozens of colleges and universities in the Greater Boston area that, combined with access to a skilled pipeline of new workers and supportive industries, made the Boston area more attractive for long-term future growth. Additionally, with so many employees working from home and remote locations, GE had outgrown the need for such a large physical campus.

Ironically—given GE’s stated reasons for exiting the state—SHU will use the property as an “innovation campus.” This will include housing for the university’s recently announced School of Computing (computer engineering, computer gaming and cybersecurity) and new programs in the STEM fields, including health and life sciences, science and technology.

The School of Computing will house two graduate programs—a master’s in computer science and information technology and a master’s in cybersecurity. It also will offer undergraduate programs in computer science, information technology, game design and development and computer engineering. SHU’s game-design and development program has been lauded by The Princeton Review.

The University will move elements of its Jack Welch College of Business (WCOB) to the new campus, including its new hospitality management program that will make use of facilities both at the GE site and at SHU’s recently acquired Great River Golf Club in Milford, Conn. This expansion is particularly timely, as expenditures in the rapidly growing global hospitality industry are estimated at approximately $3.5 trillion annually.

The SHU hospitality major addresses food and service management, lodging operations, beverage management, human resources, tourism and revenue, and pricing and data analytics. The WCOB also requires students in its hospitality management program to complete internships and has developed collaborative relationships with hotels, restaurants and related service partners. Of note, the new campus site includes a hospitality wing that contains a hotel with 28 guest rooms, conference rooms, fitness centers and a medical facility.

The university also plans to move its College of Education and business office to the site, eliminating the need to rent space elsewhere. Additionally, the purchase will allow the university to pursue partnerships with local healthcare providers, offering clinical opportunities for students in SHU's colleges of Health Professions and Nursing.

SHU’s growing community of teachers, staff, students, their parents and visitors already spend close to $56 million in the regional economy. Additional new spending is estimated at $27 million to $33 million annually. But having a local college or university also brings many additional benefits beyond economics.

Institutions of higher learning support new-business development, collaboration and incubation across a range of sciences, business and the arts that will continue serving as a beacon to current and prospective employers, manufacturers and residents. Additionally, other vocations benefit from the presence of a local college, as demand rises sharply for restaurant workers, construction crews and other less-skilled jobs.

As an example of support for regional business and organizational growth, Sacred Heart already works with a variety of Connecticut cities, towns and organizations sharing expertise and resources. SHU’s Center for Not-for-Profit Organizations, offered through the WCOB, has conducted more than 200 local projects for close to 100 regional clients. Founded 14 years ago, the center has provided strategic planning, competitive analyses, feasibility studies and marketing planning for businesses, health organizations, art associations and museums.

The university intends to provide incubator space that would allow students, in conjunction with investors and area businesses, to develop their creative ideas for new products and programs. Overall, SHU’s move to this new campus directly speaks to new-business incubation and the need for an active pipeline of skilled workers—exactly the types of innovation large corporate employers—GE included—have been clamoring for to meet the needs of today’s rapidly evolving economies.

With the purchase by SHU, Fairfield should receive payments from the state’s PILOT (Payment in Lieu of Taxes) program, which compensates Connecticut towns and cities for tax revenue they do not collect from nonprofit entities such as colleges, universities and hospitals. Those dollars are based on formulas established by the Connecticut Legislature and, in part, determined by tax revenue collected statewide. Future PILOT-related reimbursement revenue from SHU also will include growth at several local facilities now being renovated for classes, administration and housing.

Colleges and universities play a critical role shoring up the infrastructure and long-term viability of the communities and regions they call home, explained SHU President John J. Petillo. This, he pointed out, includes new manufacturing jobs and creative collaborations that help meet employer and community needs in fields like science, engineering, public education and health services.

These important economic growth stimulants are now at risk as public funding and financial aid for private colleges and universities continues to decrease. To remain competitive and successful, institutions of higher learning must continue aligning themselves and their programs with emerging industries and evolving employer, nonprofit and organizational requirements.

Sacred Heart’s purchase of the former GE headquarters property to expand its business, technology, hospitality and human services programs directly reflects this commitment to continued growth and future needs.

“This is a transformational moment in the history of Sacred Heart University, and for Connecticut,” Petillo said. “With this property, SHU has a unique opportunity to expand its contributions to education, research, healthcare and the community. SHU is vested in the success of our students and in the continued success and prosperity of the region. We are happy to be contributing toward our state’s economic growth and proud to be a continuing catalyst for the future generations of employees, residents and business owners.”

Ira Morrison is a writer and communication consultant. He has worked as a communication manager for several Fortune 500 companies and was an adjunct professor at the University of Hartford School of Communication. This piece started at the Web site of the New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe,org)

New England's shoe-business redux

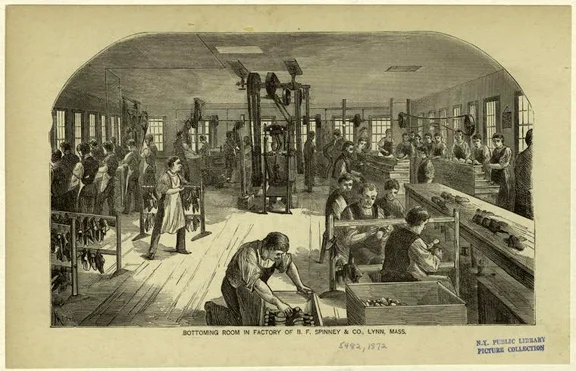

In the B.F. Spinney & Co. shoe factory in Lynn, Mass., in 1872.

From Robert Whitcomb's "Digital Diary'' column in GoLocal24.com:

From the late 19th to the middle of the 20th Century, Massachusetts was often called “The Shoe Capital of the World’’ because of its many shoe factories, most notably in Brockton but also in towns north of Boston, particularly Lynn. Most of the factories were closed as the companies either went out of business or moved their operations south in search of cheap labor, aided by new industrial air-conditioning. Same thing with the textile companies.

But the Bay State and New England in general have been pretty good at reinventing themselves. Even in shoes. Nowadays footwear companies are drawn to (or stay in) Greater Boston because of the increasingly rich design, marketing, manufacturing technology (such as robotics) and other expertise available there. Consider the following companies with headquarters operations in the area: New Balance, Puma, Alden of New England, Wolverine, Clarks, Earth Brands, Reebok, Vibram, Rockport and Converse.

A particularly evocative development is the recent move by British-owned Clarks Americas into the former Polaroid factory in Waltham. In its glory days in the ‘50s and ‘60s, Polaroid, the instant camera and film company, was considered a leader among the Massachusetts technology companies that were spouting up along the recently built Route 128. The company was called a “juggernaut of innovation.’’ (There’s been a minor revival lately of using Polaroid cameras. Like vinyl records?)

A big change since the ‘60s is that many tech companies now prefer to be in Boston and Cambridge because the executives, and their younger workers, find them more stimulating than the suburbs. The most dramatic recent example, of course, is General Electric deciding to leave its boring Fairfield, Conn., corporate campus and move to Boston’s trendy waterfront.

Gary Champion, president of Clarks Americas, succinctly explained to The Boston Globe the lure of Greater Boston:

“The skill is what brings us here, even still.’’

Having spent summers in high school working for a trucking company in Boston (on the then grubby and arson-rich waterfront) much of whose business was servicing the shoe and related business, I find this comforting.

Massachusetts’s jobless rate in December was 2.9 percent and the state’s average wages are among the highest in the nation. Massachusetts employers need more skilled workers to staff the many well-paying and sophisticated jobs available in the Bay State. That its public schools are probably the best in America, and that the state hosts world famous colleges and universities, helps to churn out great workers. But so successful are so many Massachusetts companies that they’re desperate for more highly skilled workers. In a sense, a nice problem to have!

Will these deals raise economic 'animal spirits'

“The Proposition,’’ by William-Adolphe Bougureau (1825-1905).

From Robert Whitcomb's Dec. 22 "Digital Diary'' column in GoLocal24.com.

I admire the very hard and patient labor of Rhode Island Gov. Gina Raimondo and her colleagues (presumably working with Providence Mayor Jorge Elorza’s administration) to bring some highly respected companies and quite a few jobs to Rhode Island.

The biggest recent employee hauls, all slated for Providence, will be hundreds of jobs (to start) coming to Wexford Science & Technology’s project in the 195 relocation area; 300 at Virgin Pulse (maybe in the Providence Journal Building); 100 at General Electric, and 75 at Johnson & Johnson. The hope is that those well-paid employees will be just the beginning of thousands of well-paying ones arriving over the next couple of years. (City and state official are apparently still working to bring in some Pay Pal operations, too.

We’ll see.

It was gratifying that J&J cited the presence of Brown and RISD as a reason for the project. The state hasn’t gotten nearly enough leverage from its higher-education establishments, or from its proximity to(and lower costs than) the brainiac center of Greater Boston.

A lovely change from the 38 Studios approach.

Of course, the new arrivals will each get millions of dollars in “tax incentives’’ to come to Rhode Island -- incentives that everyone else must pay for. Such incentives are the rule in every state to varying degrees. Two big recent examples – Indiana (pressed by Donald Trump) bribing the Carrier Corp. to not send 800 jobs to Mexico and Massachusetts giving many millions of dollars in goodies to General Electric to move its headquarters to Boston’s waterfront.

Companies that have loyally stayed in their states and paid taxes there without special favors must be irritated. But life is indeed unfair – and probably getting more so. The rich get richer and the poor get…. Get used to it, especially over the next four years.

The idea behind the legal bribery is that not only will these big, rich companies bring in new jobs in themselves but they’ll give many local vendors a lot of work and thus incentives to hire more people. That means not only vendors already in the area but also new ones coming in to serve the big shots. The old “multiplier effect’’.

And just by having such prestigious enterprises in Rhode Island as the ones lured by the Raimondo administration, it is argued, will boost the “animal spirits’’ of local and other business people and investors about Rhode Island. The hope is that such optimism/local pride will then help create, or lead to the import of, more enterprises, in a virtuous circle.

Will this work enough in all too cynical and negative Rhode Island to turn around the state for the long term? Who knows for sure, but I give a lot of credit to Ms. Raimondo and her staff for their labors while being denounced from all sides by those who provide few if any practical alternatives.

Chris Powell: GE's exit from Conn. might be good for the state

Paying GE to stay would incur a financial loss for Connecticut. But a state that used cash grants and tax breaks to pay GE to relocate and promise to stick around for a while would gain jobs, personal-income and property-tax revenue from GE employees, and general commerce to offset the expense.

MANCHESTER, Conn. Now that nearly a dozen other states are bidding for General Electric to move its headquarters out of Fairfield, Connecticut probably will lose the 800 jobs there. Merely to keep something it already has, Connecticut is far less able to pay and to justify paying GE's extortion than other states will be able to pay and justify paying GE to get something new.

Paying GE to stay would incur a financial loss for Connecticut. But a state that used cash grants and tax breaks to pay GE to relocate and promise to stick around for a while would gain jobs, personal-income and property-tax revenue from GE employees, and general commerce to offset the expense.

Connecticut might be able to justify paying GE to expand here. But GE isn't planning expansion. Rather, the corporation is upset about the "unitary tax" just enacted by the General Assembly and Gov. Dan Malloy, under which a corporation's worldwide income is subjected to state taxation. Many states have unitary taxation, but while it may be fair, Connecticut's avoidance of it had been an advantage in attracting and keeping businesses, just as the state's avoidance of an income tax was a draw until 1991.

Presumably Connecticut could mollify GE only by repealing unitary taxation or subsidizing GE in some way that in effect would reimburse the tax. But repealing the tax would require the governor and legislature to raise other taxes or cut spending, while reimbursing GE its new tax would invite all big corporations in the state to demand the same treatment even if they had to threaten to move out as GE has done.

If keeping GE induces Connecticut to repeal unitary taxation and start making policy changes to save money and start putting the public interest over the special interest, the corporation will have done the state a service. But the corporation also may do the state a service if it leaves, for then the state may start to realize that paying extortion to businesses is no substitute for ordinary good and efficient government in pursuit of the public interest.

With a little luck GE's departure from Connecticut would end state government's policy of pretending that mere political patronage is economic development.

xxx

New London's is the latest municipal government to "ban the box" -- that is, to remove from city job application forms the box asking if an applicant has a criminal record. State government already has done the same thing. It is said that the question discourages otherwise qualified applicants who are trying to rebuild their lives and that, if an applicant is considered seriously, a criminal records check will be done on him anyway.

This is politically correct but not persuasive. For the application forms with the "box" don't say that anyone with a criminal record will be disqualified automatically. Instead the forms with the "box" signify that a criminal record may be relevant to job qualifications, which is why applicants are supposedly to be subject to a criminal records check at some point before hiring.

That is, forms with the "box" tell the whole truth while forms without the "box" mislead.

Further, forms with the "box" deprive personnel departments of an excuse to forget to do criminal records checks. Forms with the "box" remind personnel departments to be conscientious.

That such reminders may be needed was demonstrated by the massacre in June at the church in Charleston, S.C. The perpetrator should have been disqualified from purchasing his guns because he recently had admitted a narcotics offense, but that admission was not properly recorded in federal, state, and local law-enforcement databases.

Since government databases can be mistaken and since personnel departments can be negligent, job applicants themselves should continue to be asked at the outset if they have criminal records. While it's politically incorrect, it's a lot safer.

Chris Powell is managing editor of the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester, Conn.

Chris Powell: Well-run states shouldn't need to bribe to keep firms

Back in June the leaders of the Democratic majority in the Connecticut General Assembly, having just passed another huge tax increase, including substantial business taxes, scoffed at complaints by major businesses, including General Electric, whose headquarters is in Fairfield. GE threatened to leave the state.

Senate President Martin Looney, D-New Haven, said GE was just using the tax increases as an excuse for layoffs it already planned. House Speaker Brendan Sharkey, D-Hamden, agreed, adding that GE was "fear mongering" and that tax policy couldn't be inducing the company to move. They noted that GE probably wasn't paying much in state corporation income taxes at the moment, but that was misleading. For GE's resentment seems to have been triggered by the state's change to a system of "unitary taxation," by which corporation earnings attributed to transactions out of state would be taxed here too.

Governor Malloy didn't scoff as his party's legislative leaders did. The governor took the business complaints seriously and persuaded the legislature to reconvene in special session to reduce and delay the tax increases. While this wasn't much, the governor long has been offering tax breaks and grants to induce businesses to locate or stay in the state, so he knew intimately that other states are doing the same thing and that most big businesses today have little loyalty to anything beyond money.

The other businesses that complained about the tax increases may have been mollified but not GE. There lately have been reports that the company is negotiating its relocation with Georgia and New York and that the Malloy administration is assembling a counter-offer. If GE pays little in state taxes now, it soon may pay even less.

GE most benefits the state economically not through corporate income taxes but through its huge employment, about 5,700 people here, and through the income, property, and sales taxes they pay. That would be a lot of jobs to lose.

But paying GE to stay would have its own costs. State government would be seen to have yielded to a major extortion and the other big companies that complained about "unitary taxation" and an ill-conceived tax on data processing would be tempted to try their own. Indeed, GE's extortion likely was encouraged by the extortion paid by state government last year to United Technologies Corp. for little more than the company's promise to keep its employment here steady while it expands elsewhere.

Smaller businesses, which don't have the same leverage, would be further demoralized by the unfairness of paying GE to stay, since, in effect, everybody else in Connecticut would be having his taxes increased just to keep GE and its employees happy.

This really isn't "economic development." Since it just shifts burdens from one set of businesses to another set, it's more like political patronage and corporate welfare, and it should stop.

For if Connecticut cannot attract and sustain business by virtue of its basic characteristics -- labor force skills, transportation and technological infrastructure, favorable taxation, efficiency of government, and general living conditions -- the state should work on those characteristics before it pays extortion. Surely those characteristics need much improvement.

For starters, if state government ever could regain control over government employee costs and stop its welfare system from perpetuating poverty through child neglect and abuse, it could easily forgo all revenue from big companies that might try extortion.

Imagine being able to tell GE and the world that Connecticut is so well-managed and attractive that it doesn't need to pay extortion. Of course, that would require alienating the government employee unions and welfare recipients, child abusers and their coddlers. But there may be a reason why no states are bidding for them.

Chris Powell is managing editor of the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester, Conn.

Some real and movie time with Pete Seeger

In the late spring of 1970, a group of about a dozen of us (I was along for the ride with a girlfriend of the time) spent a few hours with the mellow-voiced Peter Seeger at his 17-acre rustic homestead, in Beacon, N.Y., on a bluff overlooking the Hudson River. It had been a lush, warm spring, famous for anti-Vietnam War demonstrations. We had a cookout, at which Seeger was an affable host. He, of course, sang and played the five-string banjo, and a few others joined in making music.

Way down below on the river was a sloop that he owned that he was using in the early stages of leading a campaign to stop the likes of General Electric and other organizations from dumping toxins (some carcinogenic) into the river (which that day, despite its poisons, looked like 18th Century painting of the Rhine. Gorgeous!). It seems astonishing now to think of what we dumped into our public water, both as individuals and as institutions.

I generally disliked folk songs back then -- the lyrics seemed too sentimental and sometimes far too preachy and the tunes repetitive and clunky. I find them easier to take these days because I hear them as part of the broad flow of history. Or maybe I'm just getting hard of hearing....

Meanwhile, take a look at this segment of the very funny and sad movie The American Ruling Class. In it, Pete Seeger is walking, banjoing and singing down a road in what seems to be a very pastoral part of Greenwich, Conn., a capital of the sometimes rapacious capitalism that the old leftie hated. I think it's pretty funny, as is much of the movie, directed by John Kirby, produced by Libby Handros and with writer/editor Lewis Lapham as the master of ceremonies. He takes us to a lot of other celebrities commenting on American society in the years before the Great Crash of 2008.

Comment via rwhitcomb51@gmail.com