Jim Hightower: Trump trade plan means more offshoring of U.S. jobs

Via OtherWords.org

Like rose blossoms, a politician’s promises can be beautiful when they burst into full, glorious bloom — only to fade over time and, petal by petal, fall away.

Take Donald Trump’s glorious pledge last year to renegotiate the NAFTA trade deal and provide a “much better” deal for working families who lost manufacturing jobs as a result of it. Beautiful! This particular blossom is what convinced many hard-hit former factory workers to vote Trump into the White House.

But the bloom is now off Trump’s rosy promise, and it looks like working families will get nothing but thorns from him.

A recently leaked copy of Trump’s NAFTA plan reveals that, far from scrapping the U.S.-Mexico-Canada trade deal, White House negotiators are goosing it up with even more power for multinational corporations.

In particular, it includes new “investor incentives” to offshore thousands more of our middle-class jobs. Where did this come from? Right out of last year’s discredited and defeated Trans-Pacific Partnership, a scam intended to enthrone corporate supremacy over our own laws.

Indeed, the 500 corporate executives and lobbyists who essentially wrote that raw TPP deal have quietly been huddling with Trump’s team to draft the plan for this “new” NAFTA, the consumer advocacy group Public Citizen reports.

What about those working people Trump promised to help? They’re locked out, not even allowed to watch the negotiations, much less have a say in them. The same goes for consumers, environmentalists, and farmers. Even members of Congress are being left in the dark, allowed no voice in shaping the deal.

But I’m guessing that the six Goldman Sachs executives Trump brought in to run our economic policy do have a say, along with his daughter and son-in-law who oversee both our government and the extended Trump family’s global business empire.

It’s the same old NAFTA story: Corporate powers are at the table — and you and I are on the menu.

Jim Hightower is a radio commentator, writer, and public speaker. He’s also the editor of the populist newsletter, The Hightower Lowdown, and a member of the Public Citizen board.

Chuck Collins: Wall St., Trump hope that you've forgotten 2008

This first ran in OtherWords.org

Remember 2008 — the bank bailouts, the spiking unemployment rate, the stock market free fall?

Maybe you lost a job, got a pay cut, or saw your retirement savings or home value evaporate. Maybe you even lost your home altogether, or saw your small business wither and die.

It’s a hard thing to let go. But Wall Street is hoping you’ve already forgotten it.

That’s because their allies in Congress and the Trump administration are poised to scrap the reforms that lawmakers put in place to prevent another meltdown.

For starters, they’re trying to gut the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, the first independent agency with the sole mandate of protecting consumers against scam artists, predatory lenders, and bad actors in the financial sector.

The agency proved its mettle last year, when it caught Wells Fargo — the second biggest bank in the country — creating millions of bogus accounts without their customers’ permission. The bureau exposed that cheating and put an end to it.

Dodd-Frank, the law that created the bureau, also made rules to keep banks from making risky bets with your money.

For instance, it requires banks to keep some skin in the game by maintaining a 5 percent stake in loans they originate, so they have a stake in the success of the borrower and the loan. It also encourages banks to keep some cash on hand in case of emergencies, just like the rest of us try to do at home.

Yet lately, bankers have been complaining that financial regulation is hurting the economy. Gary Cohn, a former Goldman Sachs president — and now a Trump economic adviser — whined recently that banks are being forced to “hoard capital.”

If maintaining a prudent reserve is hoarding, then yes. And that’s a good thing.

Bankers like Cohn say abolishing these rules will help ordinary consumers. When you hear things like that, hold tight to your wallets and purses.

The truth is, cheap credit is abundant. The commercial and industrial business industries are booming. Credit card and auto lending are at record highs, and mortgage loans are almost back to their pre-2008 crisis high.

If that’s not enough for Wall Street lenders who want to gamble, they should go to the casino. And if venture capitalists want to take great risks in search of great rewards, blessings upon them. But they shouldn’t expect the rest of us to bail them out after their next binge.

What about Donald Trump? Will he protect us?

Trump campaigned as a champion for the “little guy,” beholden to no one because of his independent wealth. He smeared opponents like Ted Cruz and Hillary Clinton for being “puppets” of big banks like Goldman Sachs.

My advice? Watch what Trump does, not what he says.

After all, Trump just installed the most pro-Wall Street team our nation has ever seen. Three of his senior advisers — including Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin — have a combined 40 years at Goldman Sachs.

Now they’d like to remove the sheriff from the financial sector. If they get their way, I’ll give you better odds than Vegas that they’ll crash the economy again — and stick you and me with the bill.

Lock up your treasure. Call your lawmaker. Don’t go back to sleep.

Chuck Collins is a senior scholar at the Institute for Policy Studies and a co-editor of Inequality.org. He’s the author of the recent book Born on Third Base.

Josh Hoxie: Sucker voters give Wall Street more power and money than ever

During the campaign, Donald Trump said he wanted to fix our rigged economic system. And we can’t do that, he said, by counting on the people who rigged it in the first place.

He talked a big game about Wall Street and the big banks. He repeatedly called out Goldman Sachs, the Wall Street behemoth, by name in ads and speeches, characterizing the firm as controlling his rivals Hillary Clinton and Ted Cruz.

So it should come with some shock, at least to Trump voters, that now President-elect Trump has chosen a consummate Wall Street insider, Steve Mnuchin, for Treasury secretary.

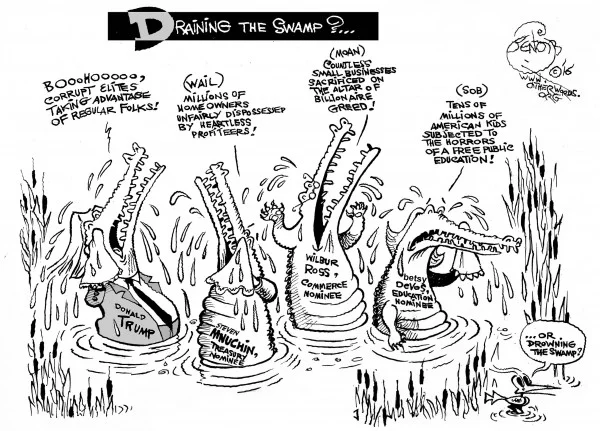

Mnuchin spent 17 years as an executive at Goldman Sachs before continuing his lucrative career as a banker and investor. Is this not the swampiest of characters that Trump vowed to drain away?

Trump’s anti-Wall Street messaging resonated with millions of voters. A poll taken just before the election showed that nearly 70 percent of undecided voters in key swing states wanted to break up the big banks and cap their size to avoid another financial crisis.

The same proportion wanted to close the “carried-interest loophole,” an insidious provision that enables hedge-fund managers to pay lower taxes than nurses.

It’s unclear whether Trump’s anti-Wall Street messaging made the difference for these voters. But it’s abundantly clear that he didn’t mean a word of it.

In Washington, personnel is policy. And Mnuchin’s appointment casts serious doubt that Trump will follow through with any of his bluster on Wall Street.

Mnuchin isn’t just any Goldman Sachs alumnus: He oversaw one of the largest foreclosure operations in the country. Mnuchin bought mortgage lender IndyMac in 2009, renamed it OneWest, and continued on as its chair through 2015 — a period in which OneWest foreclosed on more than 36,000 families.

What exactly does Mnuchin want to do while in power?

In his first announcement, Mnuchin exclaimed his “number one priority is tax reform,” promising to work with Congress to pass the “biggest tax cut since Reagan.” He claims the benefits of this tax cut will go to middle-class families, rather than the upper class.

Fortunately, tax plans, unlike campaign promises, can be easily and quickly fact checked. Unfortunately, Mnuchin’s statement comes back pants-on-fire false.

Over half of the cuts in Trump’s proposed tax plan would exclusively benefit the top 1 percent, according to the non-partisan Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. The plan would increase their after-tax income by 14 percent, 10 times more than for middle-income earners.

Mnuchin won’t be the only Wall Streeter in the Trump administration. Steve Bannon, the chief strategist for the president-elect and former head of the white supremacist “news’’ outlet Breitbart, is a fellow former Goldman Sachs employee.

The Wall Street swampiness of both Mnuchin and Bannon, however, pales in comparison to that of Wilbur Ross, the billionaire investor selected by Trump to lead the Commerce Department. The 79-year-old investor built a career on greed, exploitation and apparent tone deafness. Ross infamously whined in 2014, “The 1 percent is being picked on for political reasons.”

These former Wall Streeters will have serious power overseeing major parts of the government and the overall economy.

It’s been just eight years since Wall Street bankers had to come to Washington, hat in hand and utterly humbled, to ask for a taxpayer funded bailout. The reforms put in place to prevent a repeat of the 2008 crisis are tenuous at best — and now they’re under serious threat from the same people they were designed to rein in.

Josh Hoxie directs the Project on Taxation and Opportunity at the Institute for Policy Studies. Distributed by OtherWords.org.

Jim Hightower: Banks like Goldman Sachs don't commit crimes, their bankers do

Hey, stop complaining that our government coddles Wall Street’s big, money-grubbing banks.

Sure, they went belly-up and crashed our economy with their greed. And, yes, Washington bailed them out, while ignoring the plight of workaday people who lost jobs, homes, businesses, wealth, and hope.

But come on, buckos. Haven’t you noticed that the Feds are now socking the banksters with huge penalties for their wrongdoings?

Wall Street powerhouse Goldman Sachs, for example, was recently punched in its corporate gut with a jaw-dropping $5 billion punishment for its illegal schemes. It’s hard to comprehend that much money, so think of it like this: If you paid out $100,000 every day, it would take you nearly 28 years to pay off just $1 billion.

So imagine having to pull five big Bs out of your wallet. That should make even the most arrogant and avaricious high-finance flim-flammer think twice before risking such scams.

So these negotiated settlements between the Feds and the big banks will effectively deter repeats of the 2008 Wall Street debacle, right?

Actually, no.

Notice that the $5 billion punishment is applied to Goldman Sachs, not to the “Goldman Sackers.” The bank’s shareholders have to cough up the penalty, rather than the executives who did the bad deeds.

Remember, banks don’t commit crimes — bankers do. Yet Goldman CEO Lloyd Blankfein just awarded himself a $23 million paycheck for his work last year. That work essentially amounted to negotiating a deal with the government to make shareholders pay for the bankers’ wrongdoings — while he and other top executives keep their jobs and keep pocketing millions.

What a great example for young financial executives. With no punishment, the next generation of banksters can view Blankfein’s story as a model for Wall Street success, rather than a deterrent to corruption.

Jim Hightower is a radio commentator, writer and editor of the Hightower Lowdown.

Baby Boomers as shut-ins; Gees' infernal groves of academe

Will America soon get more realistic about the “Silver Tsunami” of Baby Boomers heading into old age? So far, the nation’s policymakers have mostly been in denial, though it’s probably the biggest fiscal and social challenge of the next few decades in America and Western Europe.

But then, most Boomers themselves have been in deep denial. Many have not saved nearly enough money. They might have been lulled into complacency by seeing how many of their parents, beneficiaries of historical luck, have lived comfortably on old-fashioned defined-benefit pensions (and Social Security), which many of them started enjoying upon remarkably early retirements.

Some of the oldest Boomers — those born in the late 1940s — have those traditional pensions; most of the younger ones will have to settle for, at the most, 401(k)s. Meanwhile, most Boomers underestimate how much ill health will beset them as they age.

But there are even bigger problems. Consider how dispersed America (capital of anomie) has become. As always, many families with children break up as couples divorce — though more and more the couples don’t get married in the first place — and people move far away from “home” to seek jobs or better weather, or are just restless. This leads to a sharp decline (accelerated by modern birth control) in the number of large but close-knit families. At the same time, there has been a huge increase in the number of younger families where only a very harried mother, who may well never have been married, is the sole parent in place, amidst a societal emphasis on “self-actualization” above family and civic duties. All these factors mean that a lot of old people won’t have the family supports enjoyed by previous generations of old people, even as they generally live longer, albeit with chronic illnesses.

There are, of course, retirement communities, with some of the high-end ones set up like country clubs. The better ones have gradations of care, from independence, within a rather tight if safe community, organized by for-profit or nonprofit organizations, to “assisted living,” which usually involves residing in an apartment and getting help with some daily tasks, and, last, the nursing-home wing for those who have slipped into full-scale dementia or are otherwise disabled.

But plenty of people can’t afford to live in a retirement community.

More realistic and pleasant for many folks are such organizations as the Beacon Hill Village model, in Boston. In this, for hundreds of dollars a year in dues you become part of a formal network of old people (and thus indirectly the networks of their families and friends) and get such services as easy access to transportation, shopping, some health-care connections and trips to cultural events. The central idea is to let people “age in place” — to stay in their homes as long as possible.

Of course, most old people eventually get very sick and end up in the hospital and/or nursing home. But the Beacon Hill approach is attractive — if you can afford the dues.

The fact is that most oldsters will have to create their own informal networks of family and friends to help look after each other as their mobility declines. And in the end, the majority must depend on family members, if they can find them. So often, obituaries report that the recent decedent was at the time of demise in some strange place with no seeming link to his or her past. It’s very often the community where a child — more often a daughter — has been living. As Robert Frost said: “Home is the place where, when you have to go there, they have to take you in.” “They” generally means a relative, not a friend.

Until then, will you have enough loyal friends to look after you when you get really old? You’d better make sure that your pals include some folks too young to live in retirement communities.

***

Hurrah for “Higher Education: Marijuana at the Mansion,” Constance Bumgarner Gee’s well-written memoir. Most of the self-published book is about her time as the wife of the very driven, peripatetic and big-spending E. Gordon Gee, who has led the University of Colorado, West Virginia University (twice), Ohio State University (twice) and Brown University, where he had the tough luck to succeed the much-liked and world-class hugger Vartan Gregorian, who had gone on to run the Carnegie Corporation of New York.

There’s lots of, by turns, hilarious and sad personal stuff in the book — about her sometimes bizarre relationship with her immensely well-paid and workaholic husband, the silly controversy about her using marijuana to treat her Meniere’s disease, her love of her riverfront house in Westport, Mass., and her ambivalent attitude toward her native South. But best is her vivid portrayal of university boards and administrations these days.

It’s not a pretty picture. The social climbing, empire-building, brand obsession, backstabbing and money-grubbing don’t present many good civic models for today’s students. The stuff at Brown was bad; it was much worse at Vanderbilt in Mrs. Gee's story. Big universities are starting to look like New York City hedge funds whose partners are driven to build ever bigger houses to show off to each other in East Hampton.

Now to reread Mary McCarthy's novel "The Groves of Academe''.

Robert Whitcomb (rwhitcomb51@gmail.com), a former editor of The Providence Journal's editorial pages, is a Providence-based editor and writer.