From ecoRI News

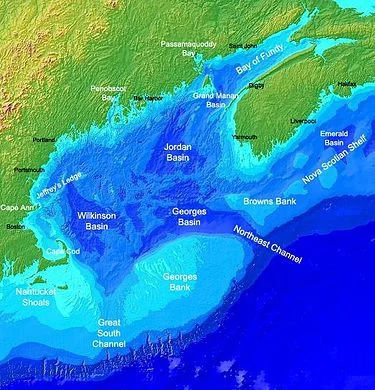

Cashes Ledge, 80 miles off the coast of Gloucester, Mass., is an oasis for sea life. The peaks and canyons of the 22-mile-long underwater mountain range create nutrient- and oxygen-rich currents that support diverse habitats throughout the 550-square-mile area.

At elevations where sunlight reaches the submerged peaks grows the largest continuous kelp forest — one of the most productive ocean ecosystem types — along the Atlantic Seaboard. Cashes Ledge is home to the depleted Atlantic wolffish, red cod, sea stars, anemones and rare sponges, and acts as a migratory pass for blue sharks, humpback and right whales, and bluefin tuna.

As a pristine example of a Gulf of Maine ecosystem, Cashes Ledge has been used by scientists as an open-sea research laboratory for decades. Relatively unimpaired by human activity or pollution, the area acts as a benchmark against which the health of the rest of the ocean is measured.

Since 2002, Cashes Ledge has been protected by the New England Fishery Management Council (NEFMC) from habitat-damaging fishing practices, such as bottom trawling and scallop dredging, in an effort to restore depleted fish stocks, including cod. Cod stocks are at historic lows — 3 percent of a sustainable level in the Gulf of Maine — because of decades of overfishing and high-risk fishery-management decisions, according to environmental groups such as the Conservation Law Foundation (CLF).

Bottom trawling at Cashes Ledge could also destroy entire sections of kelp forest and wipe out populations of sea anemones that would take more than 200 years to recover, according to the CLF.

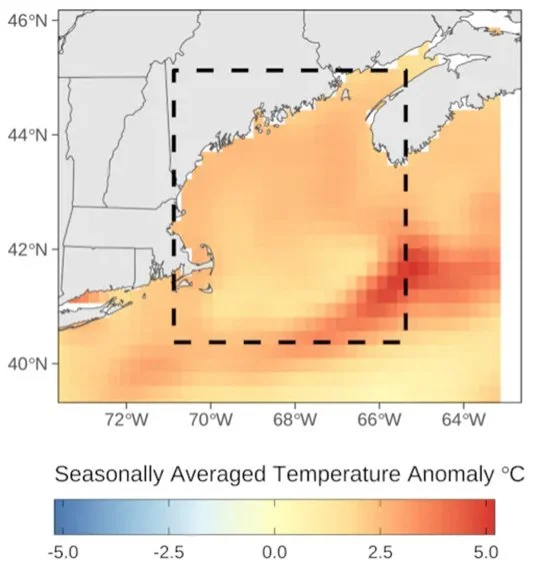

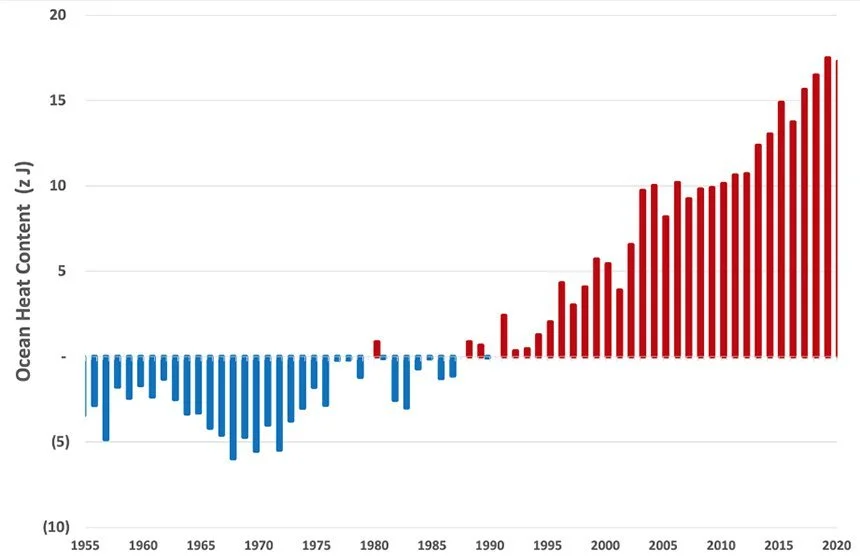

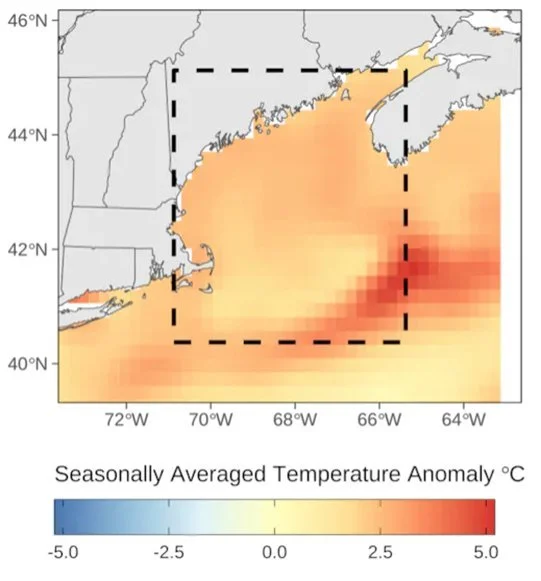

Protected areas, such as the one surrounding Cashes Ledge, also have been shown to be more resilient to climate change, and provide sea life places to adapt to warming and acidifying waters.

The Magnuson-Stevens Act of 1996 required the NEFMC to identify essential fish habitat, minimize adverse effects caused by fishing as much as feasible considering economic and other factors, and find ways to enhance essential fish habitat. The act also requires that the council update and improve habitat programs every five years. The NEFMC’s habitat management plan was due for a five-year review in 2004, but is still incomplete. The plan, titled the “Omnibus Essential Fish Habitat Amendment 2,” is currently in draft form and is open for public comment until Jan. 8.

The current draft offers a range of possible conservation alternatives, each made up of one or more possible protected areas in a geographic region encompassing the Gulf of Maine, Georges Bank and southern New England. Each possible protected area was determined using multiple analyses, including the Swept Area Seabed Impact model, and other information such as analysis of juvenile groundfish distributions, combined with information about the current status of various stocks and their affinities for vulnerable habitat types.

After the public comment period closes, the NEFMC will consider each comment and then choose the alternatives that it believes will best protect essential fish habitat from the negative effects of fishing to the extent feasible considering economic and other factors.

The CLF, an organization that advocates for increased protection of ocean habitat in New England, claims that many of the alternatives in the draft Omnibus Habitat Amendment would reverse protections previously granted to vital areas in New England waters in favor of shortsighted fishing-industry interests. The groundfish and scallop industry, for example, is pushing to reduce the area currently protected around Cashes Ledge by 70 percent.

According to a September brief by the Pew Charitable Trusts titled “Risky Business: How denial and delay brought disaster to New England’s historic fishing grounds,” Georges Bank could lose 96 percent of its remaining protected area, despite cod populations being at only 8 percent of a sustainable level. The brief states, “Overall, if the NEFMC chose the smallest closed-area option for each subregion, the total area afforded year-round protection would drop by 71 percent to just 1,909 square nautical miles” — a reduction roughly the size of Connecticut.

According to Shelley, protected areas like Cashes Ledge are essential to the long-term health of New England’s fisheries. Older and larger fish are vital to the recovery of depleted populations, he said, because they experience greater reproductive success than their younger counterparts. Protected areas have been shown to contain more numerous and older fish than unprotected areas and become incubators for neighboring waters.

Shelley said California has experimented with habitat closures as a way of increasing fish stocks. He said fisherman initially opposed the closures, but many came around after experiencing an increase in catch along the edges of the protected areas.

In another example, cited in the Pew brief, “the biomass of scallops across the New England fishery region increased dramatically in association with the closures on Georges Bank. New Bedford, Massachusetts, has the highest fishing revenue in the nation because of scallops.”

Many New England fisherman want to reopen protected areas such as Cashes Ledge to fishing because there are more fish in them, but according to Shelley more abundant fish populations in closed areas prove the protections are working and should remain in place or be expanded. If the protected areas are reopened, he said, fisheries will revert back to depleted states.

More of New England’s waters need to be protected, not less, according to Shelley. He said the Omnibus Habitat Amendment isn’t going to provide that result.

“In this case, preserving the status quo is better than the preferred alternatives of the NEFMC,” Shelley said.

In early December, 138 marine scientists and academics signed a letter to National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) fisheries officials expressing deep concern about any proposals from the NEFMC that would significantly reduce habitat protection. Signers include leading names in marine and fisheries biology such as Daniel Pauly, Callum Roberts and Sylvia Earle.

“In terms of area alone,” they wrote, “the Amendment offers no alternatives that would (expand) the overall area protected in the region. Given the current state of some of the managed fish populations, protecting more, not less, habitat would seem to be an alternative worthy of consideration.”

The letter suggests enacting more comprehensive fishing-gear restrictions in protected areas, instead of only prohibiting bottom-tending gear. It also contests the arguments in support of diminishing habitat protection.

“Under certain scenarios,” the signers wrote, “a smaller amount of diverse habitat may have greater ecological benefit than a larger amount of lower value (habitat). But we are not persuaded that there is sufficient evidence that this scenario can be applied here with a high degree of safety or certainty. The (amendment) does not make a strong case that the new network of (protected habitat) will be a net gain or even maintain the ecological status quo for the region as a whole.”

The letter concludes that reductions in habitat protection would be highly unwise and unsupportable by current science.

“Too often, NEFMC has ignored or downplayed scientific data in favor of the short-term economic interests of the fishing industry,” Peter Baker, director of Northeast U.S. ocean issues for The Pew Charitable Trusts, wrote in a recent blog post. “That’s the sort of decision-making that brought the region to its current state: a federally declared fishery disaster that has required tens of millions of taxpayer dollars in assistance. It’s time to start listening to the science.”

More of the waters and seafloor identified as important by scientists that cod need to spawn, feed and mature should be made off-limits, according to Baker.

“Habitat is where fish make more fish. And what New England needs now is more fish,” he wrote. “Unfortunately, New England’s regional fishery managers have proposed a plan that could actually result in the opposite, a dramatic reduction of habitat areas.”

To help the public focus their comments on the alternatives likely to be chosen, the NEFMC released its own preferred alternatives prior to the comment period. In most cases, the preferred alternatives are not the “worst-case-scenarios” many conservation groups cite to bolster their arguments.

The NEFMC has suggested maintaining one existing large closed areas in the western Gulf of Maine, and the eastern Gulf of Maine, currently unprotected, would stand to gain protections from the amendment. However, in most cases, the council’s preferred alternatives reduce the overall area currently protected.

Current closed areas on the left are generally larger than those preferred by the NEFMC on the right. The NEFMC didn’t selecte any preferred habitat alternatives in the Georges Bank or Great South Channel/Southern New England subregions, but its analysis does include these subregions and offers a variety of alternatives. (Omnibus Essental Fish Habitat Amendment 2 Public Hearing Documment)At a public hearing for the draft Omnibus Habitat Amendment in Warren, R.I., in early December, clam, lobster and scallop fishermen spoke out in favor of specific alternatives that would open areas currently closed to fishing, prevent areas currently open to fishing from becoming closed, and relaxed fishing-gear regulations to improve their catch.

One surf-clam fisherman said he had been operating in the same fishing grounds on the Nantucket Shoals for 35 years without negative impacts. He requested the Omnibus Habitat Amendment include an exemption for surf-clam fishing, including in closed areas, because of the relatively benign gear used by his fishery.

Jerry Elmer, of CLF Rhode Island, was the sole conservationist to testify at the hearing. “This fish habitat amendment should be viewed as an opportunity to enlarge protected habitat,” he said.

Jeremy Collie, professor of oceanography at the University of Rhode Island, testified in favor of alternatives that would continue year-round closures of the most vulnerable habitat on northern Georges Bank. He said it would be a mistake to allow bottom fishing in these areas.

In a follow up e-mail to ecoRI News, Collie wrote that he generally agrees with the options favored by the NEFMC and that he supports the council’s analysis showing that the favored alternatives will result in mostly neutral or positive economic and habitat impacts.

Written comments on the draft Omnibus Habitat Amendment can be submitted via e-mail to nmfs.gar.OA2.DEIS@noaa.gov, subject line: “OA2 DEIS Comments.”

Kevin Profit wrote this for EcoRI News.