David Warsh: Getting personal about the Israeli-Hamas warTheY

Hamas logo

The Israeli flag

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Is it possible to criticize Israeli policy in Gaza and the West Bank without being anti-Semitic? The question seems worth asking, even if it almost certainly means being called anti-Semitic by some. Surely it is possible to deplore Hamas without being called anti-Palestinian.

I don’t know what to do with this except to be personal about it.

I grew up in a suburb of Chicago in which racism was pervasive, though mostly polite, because no people of color lived there. Unspoken replacement theology held sway – that is, the premise that Jews, followers of the Old Testament – the Hebrew Bible – eventually would be converted to the principles of the New Testament, the Christian Bible.

Folkways of the village in the Fifties exhibited some pretty strange ideas about gender, too. The use of atomic bombs and carpet bombing against civilian populations during World War II raised few objections. And as for the indigenous populations we had displaced? The hockey team was named for them.

A large part of my education since has involved escaping those prejudices, by degrees, via participation in “movements” of various sorts: college, civil rights, anti-war, pro-women, and now, opposition to Israel’s “Second War of Independence;” that is, its special military operation in Gaza.

Revolted as I was by the Hamas raid, my first reaction to the news of the massacre of some 1,200 innocents was to ask myself what Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu should have done? I had grown up to become a member of a Congregational church; I could use my confirmation instead of a birth certificate to obtain a passport, or so I was told. For a time, I had been a Zionist: I knew a good deal about the Holocaust; I had thrilled to the film Exodus in high school.

Netanyahu should have turned the other cheek, I thought, called out Hamas to worldwide disgust and scorn, and resigned. It took only a day to realize that recommending the Sermon on the Mount to the Israeli Defense Force was no solution. That set in motion this skein of thought.

I had never seen, until I came across the other day, , in an article in The Atlantic, President Dwight Eisenhower’s advice in a letter to one of his brothers, in 1954, in the early stages of the Cold War:

You speak of the “Judaic-Christian heritage.” I would suggest that you use a term on the order of “religious heritage” – this is for the reason that we should find some way of including the vast numbers of people who hold to the Islamic and Buddhist religions when we compare the religious world against the Communist world. I think you could still point out the debt we all owe to the ancients of Judea and Greece for the introduction of new ideas.

Advice as sage today as it was then. Even much-loathed former Commies might be included in the heritage of humanity today. I’ll leave it to historians, Biblical scholars, ethnologists, anthropologists, and sociologists to pick apart the differences. But theologian Paul Tillich’s phrase “Judaic-Christian heritage,” which offered such comfort during the years after World War II, is no longer part of my vocabulary.

Having said this much, I must come to the point. I am aghast at the Israeli government’s invasion and occupation of Gaza; appalled by its plan to occupy the territory after the slaughter stops; embarrassed by the United States’ veto of the 13-1 United Nations Security Council resolution calling for an immediate cease-fire.

I object to the congressional and donor bullying of university presidents. The American newspapers I follow seem to have been somewhat intimidated as well. (Here is a long view of the situation in The Guardian that makes sense to me.) The stain on the reputations of the leaders and policymakers involved, including those in the United States and Iran, can never be erased.

I have had this privilege of writing this column, called Economic Principals, for 40 years. I couldn’t live with myself if I didn’t say this much about current events in the Middle East. It is, however, as much as I have to say. I’m against the war in Ukraine, too, but after twenty years of following its genesis, it is a problem I know something about.

The relevance to these matters of economics should be clear, at least intuitively. I pledge to work harder to spell it out.

xxx

Swedish Television does an excellent job on its short profiles of each year’s well Nobel laureates. The link offered here last week to their visit with Harvard economist Claudia Goldin didn’t work. Here is one that does. At fourteen minutes, it is well worth watching.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

Llewellyn King: When people come to love to hate

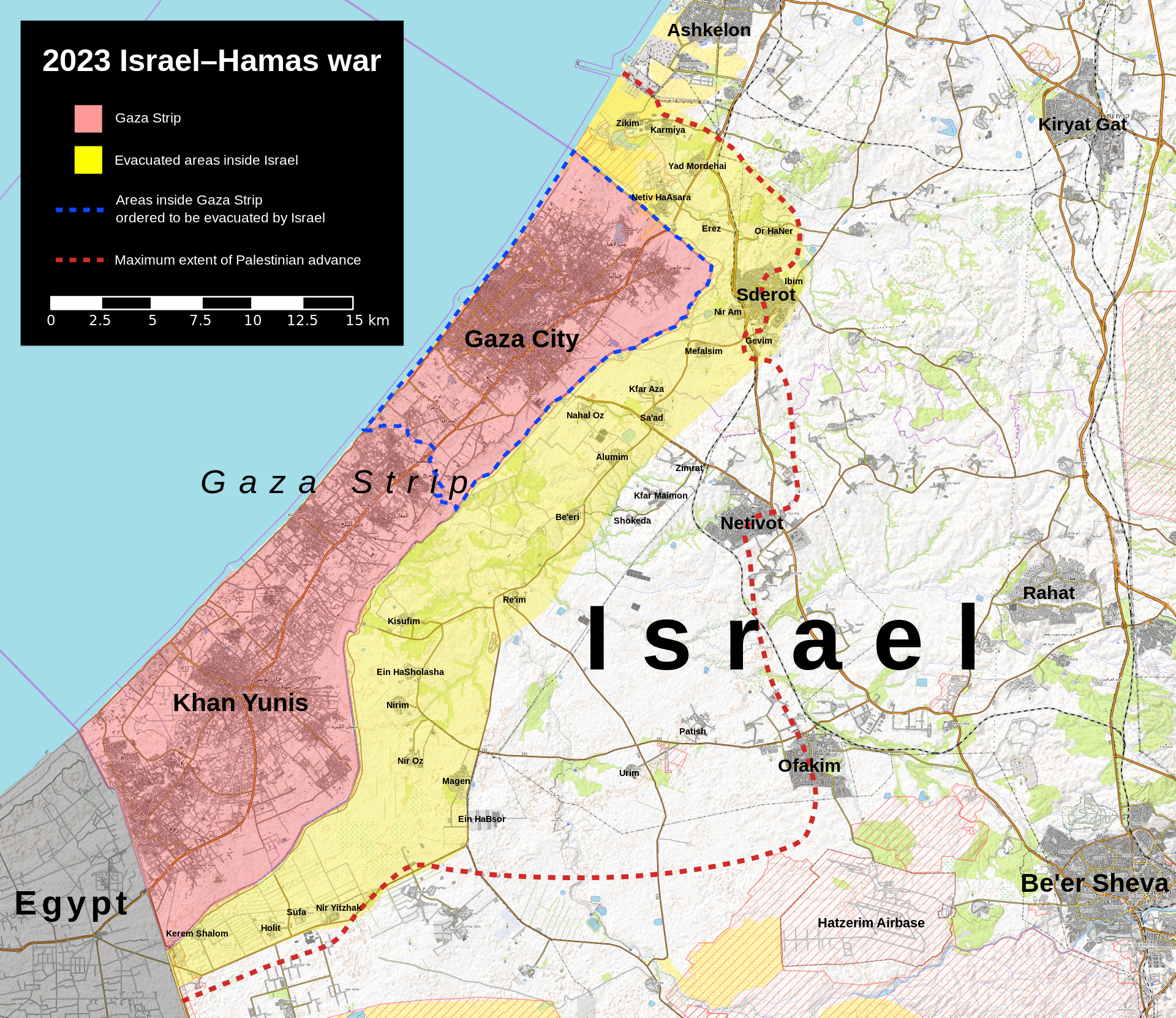

Hamas−Israel conflict at start of war, on Oct. 7-8.

— Photo by Ecrusized

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Many years ago, I was mugged in Washington.

I was looking for an informal club of the kind that sprang up after hours around big newspapers. These “clubs” were usually just an apartment with beer, liquor and card games for those of us who finished work after midnight.

The club I was looking for was on 14th Street, which was considered a bad part of town. I never got there: I was jumped and punched by a group of teenagers, who threw me to the ground and took my wallet.

My colleagues at The Washington Post brushed it off as being my fault, a self-inflicted wound — no excuses for my nocturnal wanderings.

I was bruised and felt ashamed of my stupidity. But Barry Sussman, an editor, said, “Llewellyn, you didn’t mug yourself.”

It is a sentiment that comforted my shaken self then and has stuck with me. Incidentally, Sussman was the unsung hero of the Watergate story: He edited the reporting as it came in.

My initial reaction to the carnage in Israel was, “What happened to Israeli intelligence? Where was the vaunted Mossad? By extension, where was the CIA, known to work closely with Mossad?”

Once on the Golan Heights, an Israel Defense Forces officer stood with me and boasted about how, with American-supplied gear, the military could listen to telephone calls in Jordan or watch a Syrian soldier on the plain below leave his tent to pee in the night.

So where was the surveillance, and what of human intelligence?

Thousands from Gaza went into Israel every day to work. Surely someone would have seen something; someone would have blown the whistle on Hamas’s intention to wreck mayhem on innocent Israelis — 1,400 were butchered.

Anthony Wells, a retired intelligence officer and author, who uniquely served in both the British and American intelligence services, told me in an interview on our television program, White House Chronicle, that the administration of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu was partly to blame. He said the prime minister had leaned toward Hamas, ignoring the Palestinian Authority, and sometimes ignoring Mossad. This, plus political unrest in Israel over Netanyahu’s plan to curtail the power of the Supreme Court, added to the intelligence failure.

But Israel didn’t mug itself.

The planners of the industrial-scale murder of Israelis at a music “festival for peace,” of all things, had to know that Israel would take terrible revenge; that the hurt to the people living in the Gaza Strip would exceed the hurt brought to Israel; that the vengeance would be swift and terrible.

I have noticed that where there is long-enduring hatred, as between the Greeks and the Turks, the Protestants and the Catholics in Northern Ireland, and the Shona and Ndebele in Zimbabwe, hating has its own life. People come to love to hate, to revel in it, even to find a kind of comfort in it.

Hatred also is taught, handed down through the generations.

In the Arab-Israeli conflict, the Arabs have come to treasure their suffering and to love their hating. But, as Wells told me, wars of vengeance have a price: Witness the U.S. response to 9/11 with the invasion of Afghanistan.

The suffering on both sides in the Israel-Gaza conflict is hard to process. The screaming of wounded children, the hopelessness of those who won’t be whole again, the agony of those who pray for death as they lie under rubble, hoping only for quick release.

The Israeli-Palestinian peace process is now put asunder. It went on too long without peace.

David Haworth, the late English journalist, said, “I’m tired of the process, where is the peace.?” Exactly. Now it may be decades away as Israel digs in and the Palestinians ramp up their devotion to victimhood.

The blame game for what happened is in full swing: anger at the intelligence failure; the national distractions in Israel, initiated by Netanyahu; the slow response by the Israel Defense Forces.

I must remind myself over and over again, as my heart goes out to the people of Gaza, and the generations which will pay the price, that Israel didn't mug itself: It was invaded by terrorists for the purpose of terror.

My parting thought: The mass killing of the kind in Israel and Ukraine diminishes all of us. It makes the individual, far from the slaughter, feel very insignificant — and lucky.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Raja Kamal and Arnold Podgorsky: Our steps to end Gaza war

If a biblical saw could carve Israel out of the Middle East and to drift toward Cyprus as an island, the Palestinian-Israeli conflict would disappear. As no one wields such a mighty weapon, the antagonists must learn to survive with the neighbor they have. Since modern Israel's founding, in 1948, Arabs and Israelis have gone to war numerous times. Not counting the two Intifadas and many smaller skirmishes, Israel and its neighbors fought wars in 1948, 1956, 1967, 1973, 1982, 1993, 1996, 2006, 2009, and 2014 – more than one war each decade of Israel’s short history. Over time, the faces of Israel’s adversaries have changed and Israel achieved peaceful resolutions with Egypt and Jordan. More recently though, religious and demographic changes inside both Israel and its adversaries have produced an increasingly intractable situation.

In Israel’s first four wars, its enemies were nation-states with conventional military forces – principally Egypt, Syria and Jordan, supported by other Arab countries. Adversaries and targets were clearly defined; the conflicts were relatively brief and the strategic results were unambiguous. The Six-Day War of 1967 resulted in Israel becoming a de facto regional military superpower. In the wake of the October 1973 war, the Arab countries realized that Israel could not be defeated militarily.

Today, Israel’s most ardent enemies – Hamas in Gaza and Hezbollah in Lebanon – are driven by extreme religious ideologies. The approach that Israeli leaders have deployed to counter these foes has offered but brief advantages. Israel’s reliance on “hard power” has not and, in the long run, cannot pave a road to peace. As a result conflicts erupt easily and frequently.

Each time Hamas and Israel engage militarily, any peaceful solution becomes more elusive and unachievable. The repeated fighting is increasingly costly to Gaza’s trapped population as Israel and Hamas become more aggressive in the use of lethal weapons and Hamas deploys human shields. Hamas rockets targeting Israel are more sophisticated than those used in previous wars, while Israel deploys deadly, contemporary weapons, including drones. The result is tragically high casualty-counts displayed on global networks and social media.

As Israel’s enemies have grown more ideologically extreme, so too has Israel. Israel has its own religious and ideological extremists, and the current coalition government reflects no true commitment to making peace. Seeing no historical evidence that concessions produce peace, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s own Tea Party ties his hands and limits what he can offer to the Palestinians. Leaders on both sides of the conflict dictate policies that harden attitudes and tighten the knots at the core of their disputes.

Gaza is the tragic focus of the conflict, but it could also be the crucible through which a solution is forged. Gazans often describe their home as the largest jail in the world. With 1.8 million inhabitants living in only 139 square miles, it is one of the most densely populated places on Earth. Israel’s total blockade of Gaza leaves the area’s economy in shambles, with an unemployment rate approaching 50 percent. The latest war will surely make matters worse. With restrictions on travel, import and export, fishing rights and banking, the quality of life in Gaza has been deteriorating for a decade or more, yielding hopelessness and the rise of religious fundamentalism. To counter these trends, a paradigm shift to “soft power” and economic development is desperately needed.

The killings of Egyptian President Anwar Sadat and Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin left a vacuum in which few could move the needle toward peace. No Israeli leader since Rabin has had the creativity or mandate to advance toward peace in a meaningful way, while the refusal of many Palestinian to countenance Israel’s existence under any conditions has stifled serious discussion. Lacking vision, leadership, leaders on both sides have been mere guardians of the status quo.

As a nation-state itself, it falls to Israel to make the bold move to confirm its moral leadership and provide Gaza a path to integration as a member of the civilized world. Netanyahu should unilaterally propose the following actions for peace:

1. Easing significantly the blockade of Gaza.

2. Allowing and encouraging economic activity there, including the freer movement of people in and out of Gaza, fostering employment and education.

3. Removing restrictions on funds entering Gaza.

4. Providing tax incentives to Israeli firms to open plants adjacent to Gaza where Gazans might seek employment.

5. Removing restrictions on exports from Gaza.

6. Spearheading an international “Marshall Plan” for Gaza to help rebuild the economic infrastructure.

These actions would accelerate the rebuilding of Gaza. They would improve Gazans’ standard of living significantly, helping to reduce the hopelessness that drives many to extremism. Collectively, these actions would be a far better investment in Israel’s security than any weapon. What would Netanyahu require in return?

1. Hamas agreement to a truce, to disarm Gaza, and to support the above package.

2. An international plan and pledge to monitor that disarmament, including eliminating all rockets currently possessed by Hamas and eliminating tunnels.

3. An international force of about 25,000 to oversee border security between Gaza, Israel and Egypt.

While these steps alone would not achieve a lasting peace between Israel and the Palestinians, they would significantly improve the situation on the ground and establish a framework for a future status agreement. Citizens of Gaza and Israel’s neighboring towns would have the opportunity, over time, to develop the habits of peace. Netanyahu would emerge as a visionary leader, earning the global respect shared by Rabin and Sadat. Netanyahu must be willing to make bold decisions to avert the next war.

Raja Kamal is senior vice president of the Buck Institute for Research on Aging, based in Novato, Calif. Arnold Podgorsky is an lawyer and president of Adas Israel Congregation in Washington, DC, a Conservative synagogue. This column states their personal views and not the official views of either organization.