Thomas C. Jorling: How to use the highway system, new building codes to address climate change

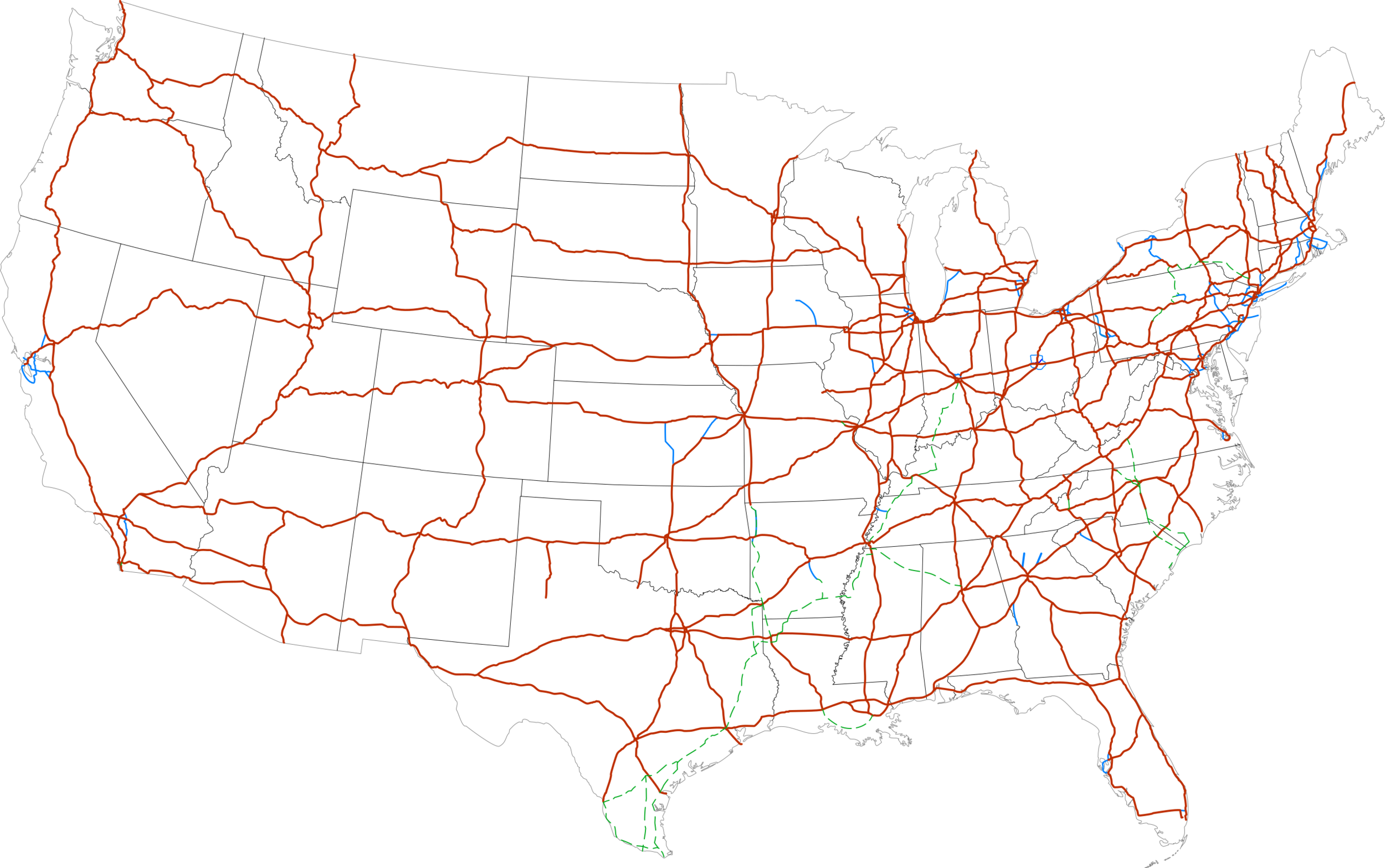

Map of the current Interstate Highway System in the 48 contiguous states

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

Climate change is real and accelerating. It requires an urgent response that focuses all the strategies and tactics necessary to stabilize the Earth’s temperature regime.

The objective to guide research, development and implementation is straightforward: Achieve an all-electric economy. Simply put, all sectors of energy use—agriculture, transportation, industrial, residential, business, etc.—must transition to electricity. Where liquid fuels are necessary, such as aviation, they must be produced from biological processes.

This objective, however, can be satisfied only by transforming electricity generation to alternative—non-combustion—sources that convert into electricity the energy from the inexhaustible clean supply provided by the sun and ecosystem, primarily wind and solar.

As the transition occurs, existing fossil-fuel energy will be replaced and future growth will be accommodated. It is a transition that has historical examples and precedents: wood to coal, oil and gas; horses to automobiles; hard lines to cell phones, among many other examples of progress. Dislocations associated with these transitions have occurred, but they were quickly overcome by innovation and adaption. This has been the story of human progress.

While some elements of the transition require intervention at the national level such as the Clean Air Act addressing health-damaging air pollution, the need now is for federal and state legislation and policy to discipline and make fair the transition from coal, oil and gas.

Needed: A smart grid

There is no question the nation needs a “smart grid” to facilitate the delivery of alternatively generated electricity across geography and time zones. This raises the question: Can such a grid be created without defiling the countryside and disrupting ecosystems? The answer is yes.

A significant portion of the cost of the Interstate Highway System was incurred securing rights-of-way. As a transportation system, it has been highly successful. One consequence, which is greatly unappreciated, is that these rights-of-way represent a tremendously valuable federal and state asset that shouldn’t be limited to concrete and asphalt.

Even a quick look at a national map of the Interstate Highway System reveals a network connecting rural America and urban America. The highway network can also be a connection between and among the same areas for electricity generation, management and distribution. Buried, reinforced conduit along the rights-of-way of the system can connect—and make smart—the grid, enabling electricity to be moved and delivered efficiently and effectively. This will allow electricity, from generation to user, to be managed back and forth across the country as needed in response to changing seasons, weather and time of day.

More than transportation

We need to change these rights-of-way from single-use to multiple-use. This network, already invested in by the public, can accommodate not only an electric grid, but also pipelines and even elevated high-speed rail. Letting the asset represented by this extensive right-of-way network be underutilized is a travesty. It can and should be used for multiple national needs. All of which can help address climate change.

The development of a multiuse right-of-way based on the Interstate Highway System to accommodate a smart electrical grid, expansion of broadband and other networks presents opportunities and challenges for higher education. Among opportunities, use of the highway network can enable rapid expansion and availability of broadband, not just to institutions but to communities all across the country. This would enable all citizens, families and communities to benefit from full access to the internet and overcome the disparities of access to make higher education more available to everyone. Among challenges, using the Interstate Highway System as a multiuse asset will require the innovation of higher-education institutions (HEIs). Ways to stimulate that innovation could include, for instance, a competition among HEIs, especially those with technically oriented capability, to design easily and rapidly installed, low-cost conduit structures on or in the ground for the electric grid on the interstate highway network. HEIs should become centers of innovation and excitement for the societal transformations that are going to occur as the U.S., indeed the world, addresses the challenges of climate change and the sustainability of communities and infrastructure in the quest for a better future.

We do not need to establish new rights of way across the American landscape taking any more forest or agricultural land that plays so important a role in capturing and storing carbon in wood, fiber and soil.

Another grossly underutilized resource is the extensive areas of roofs on structures, especially flat-roofed structures and the parking areas adjacent to the structures, that now cover extensive areas of our landscape. Before human settlement and the expansion of built-up land, these areas captured the energy of the sun in what ecologists call primary productivity: that is, plant photosynthesis converting sunlight into biomass in complex ecosystems. These areas can once again be used to capture the sun’s energy and convert it to electricity.

To this end, the country needs to adopt national building codes to require:

New building structures to be physically oriented and designed, to the extent possible, for maximum use of sunlight, both passive and through photovoltaic systems.

Every flat-roofed structure newly constructed that has a surface area greater than half an acre should be required to install rooftop solar photovoltaic panels.

All current flat-roofed structures greater than an acre should be required to retrofit the roof with solar panels within five years. Creative partnerships between owners, utilities and solar investors and installers could flourish in this effort.

All parking lots greater than an acre should be required to install elevated solar panels. This can be done by the parking lot owner or leased for a nominal or no charge to a solar panel installer.

All forms of federal assistance (such as loans, guarantees, grants or tax benefits) for housing and economic development, should be conditioned on financially support measures to achieve energy efficiency and install solar electric-generation opportunities.

These achievable, cost-effective steps can result in the production of large amounts of electricity and contribute significantly to achieving an economy without fossil fuels. These widely distributed systems, connected through a smart grid, in protected conduits (rather than vulnerable suspended wire systems), could assist in making our economy sustainable and the people supported by resilient and reliable electric power.

Thomas C. Jorling is the former commissioner of the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation and former director of the Center for Environmental Studies at Williams College among other key posts.

The average insolation in Massachusetts is about 4 sun hours per day, and ranges from less than 2 in the winter to over 5 in the summer.

Tim Butterworth: Some impressive examples of American 'socialism'

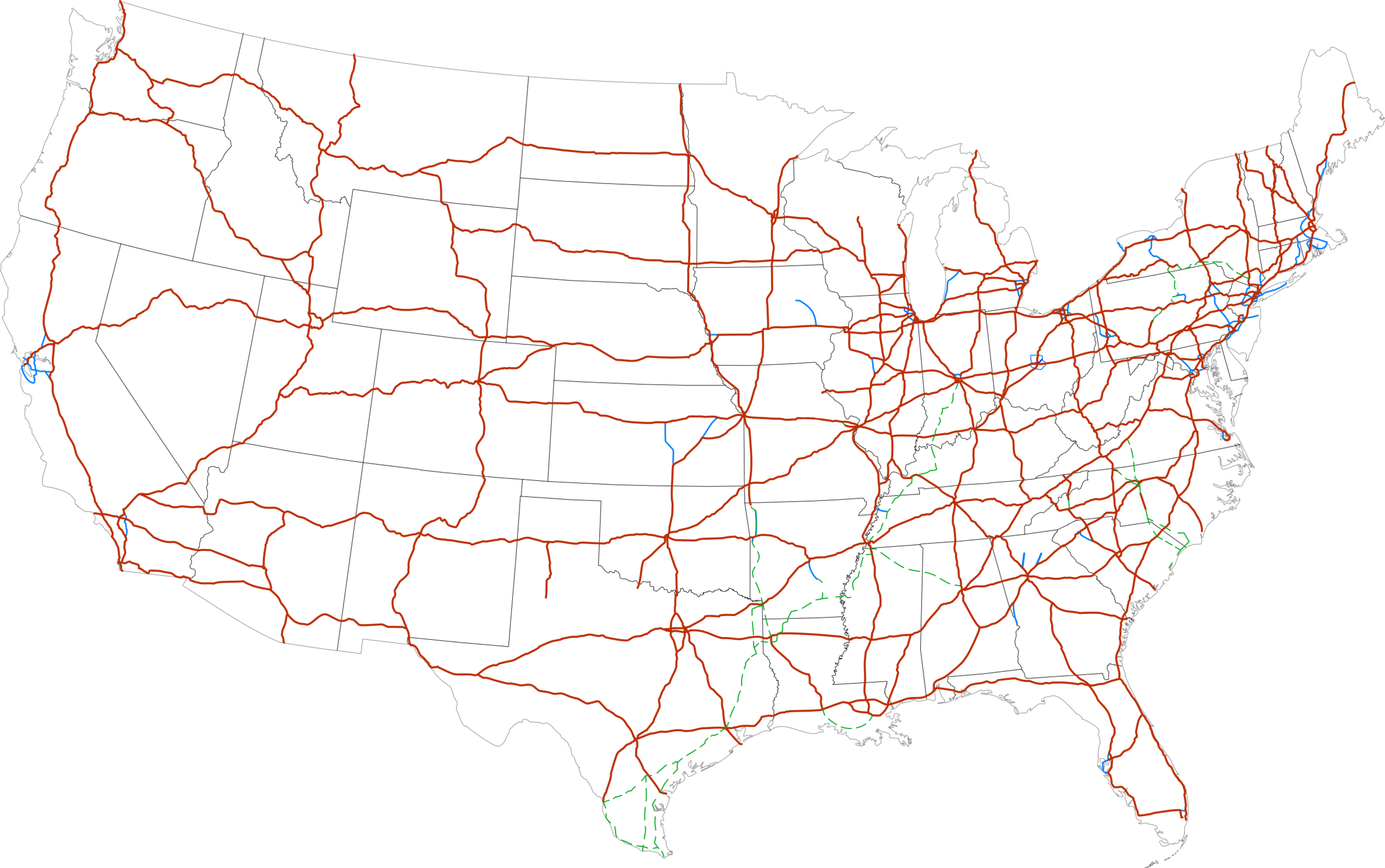

Socialist system? Map of the Interstate Highway System in the 48 contiguous states. Alaska, Hawaii and Puerto Rico also have Interstate Highways.

From OtherWords.org

CHESTERFIELD, N.H.

From single-payer health care to climate change, the 2020 Democrats have ambitious plans. But these new, grand, and green deals aren’t as radical as some make them sound. In fact, big public projects are what made America great.

When President Dwight Eisenhower first took office ,in 1953, America had been buffeted by the Great Depression of the 1930s and World War II in the 1940s. The Cold War put us in competition with Soviet “five-Year Plans” and Chinese “Great Leaps Forward.”

Eisenhower was concerned that soldiers would return home to closing factories. So Ike pushed for massive infrastructure spending, creating what was ultimately named the “Dwight D. Eisenhower System of Interstate and Defense Highways.”

Congress funded a half-century of highway construction, building 47,000 miles — the biggest public works project in the history of the world. It cost $500 billion in today’s dollars, with 90 percent coming from Washington and 10 percent from the states.

The Interstate Highways transformed America

In 1919, it took a month or more to drive cross-country; the record today is a little over 24 hours. Automobile ownership skyrocketed, gasoline sales jumped, motels mushroomed, the suburbs flourished, and malls were built. Construction companies, automakers, and oil companies flourished, too, along with their workers.

There was a downside, of course. Rail and other mass transit were marginalized, urban sprawl spread across the land, the daily commute grew longer, and our carbon footprint grew bigger, as multi-lane highways destroyed urban communities.

Still, it puts lie to the chant that “the U.S. has never been a socialist country!” After all, we drive on socialist, government-owned roads.

Meanwhile there’s almost universal support for Social Security, our government social insurance. And half the country — including Medicare and Medicaid recipients, veterans, and federal elected officials — receives some form of socialist, government-funded health care.

Consider also the Tennessee Valley Authority, a federally owned corporation created by Congress in 1933. Tennessee and five nearby states were devastated by poverty, hunger and ill health. Only 1 percent of farm families had indoor plumbing, and about a third of the population in the valley had malaria.

Starting in 1933, our taxes paid to build TVA power plants, flood control, and river navigation systems. In 1942 alone, the construction of 12 hydroelectric and one coal steam plant employed a total of 28,000 workers.

Today the TVA is a federally owned corporation with assets worth over trillions. And while Republican Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell rails against socialism, half of his constituents in Kentucky buy cheap, publicly produced TVA electricity. Free-market, for-profit, capitalist power states often pay twice as much.

Like our highway system, we need to change our TVA to meet the challenges of climate change. But that means better priorities and more investment, not less.

Federal taxes paid for the highways and the TVA, which are now supported by gasoline taxes and electric bills. In those years of great public works projects, the wealthy elite paid a much greater share of their income in taxes, with the highest marginal tax rate reaching 94 percent.

Claiming that government is the problem, not the solution, administrations since the 1970s have reduced that top rate over and over. The 2017 tax law again reduced the top rate for billionaires, creating great fortunes for a few, and great national debt, but not great public works.

Let’s get past the S-word — socialism — and have a real discussion on how to build an America that’s great for all of us.

Tim Butterworth is a retired teacher and former state legislator from Chesterfield, N.H.

When driving was fun

Route 91 south, in Wheelock, Vt. Route 91 north of the Massachusetts line has usually been a remarkably open road, and it goes through lovely rolling countryside along the Connecticut River.

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

News of the imminent completion of Interstate Route 95 – after 61 years! – by finally filling a short New Jersey-Pennsylvania gap, brought back memories of the joy of being on the road in the early days of the Interstate Highway System. As a kid with a driver’s license minted in 1964, I drove all over the Northeast, at first using my father’s red Jeep and then a used VW bug that I bought. It was my favorite car of all time, although with the gas tank over the driver’s lap, it was a deathtrap.

It was all about freedom!

I’d happily take off in the middle of the night, when there was little traffic, to go skiing in New Hampshire or down to the Cape. For that matter, there was far less traffic during the day than there is now. That’s partly because there are many more people now, and partly because building more and wider roads draws more traffic, in a kind of Parkinson’s law (“expenditure rises to meet income’’). I was struck by how bad things had become when, a few years ago, my family and I, just off the plane at Logan Airport, found ourselves in a massive traffic jam in downtown Boston – at 2 a.m.!

Back in the ‘60s, the roadside amenities, especially the Howard Johnson restaurants alongside the more important Interstates, were also delightful.

But because of crowding, texting and crumbling infrastructure, driving on the Interstates, especially in the crowded Northeast, now is often very unpleasant amidst the anger and aggression of so many drivers. How to make it less so: Spend more money on mass transit!

Boston University economist Barry Bluestone discussed this in a piece in The Boston Globe about the worsening nightmare of driving in Greater Boston. Traffic congestion isn’t as bad yet in Greater Providence – far fewer people -- but it is getting worse, in part because we have far thinner public transit than Massachusetts. Indeed, our best mass transit is Massachusetts-based: MBTA commuter trains.

Bluestone notes that traffic congestion in morning and afternoon/evening commutes in Greater Boston means that the average driving speed then is now just 18.4 miles an hour. “That means the typical commuter is now spending around 15 hours a week sitting in traffic — or 720 hours per year.’’ That’s time that could otherwise be spent making money, sleeping, sex and a plethora of other productive activities. Sitting trapped in traffic for hours a week is also bad for your health.

But, Bluestone writes, “if we were somehow to move just 13 percent of the daily commuters off the road onto public transit — about 195,000 — highway flow analysis suggests that the average speed during commuting hours could be doubled to more than 37 mph— still well below the highway speed limit. But even that improvement would save the typical commuter about 7.5 hours per week in commuting time or 360 hours per year.’’

“Yet there is an additional benefit. The typical commuter who drives 6,000 miles per year in commuting now spends around $821 a year in fuel. Doubling the average speed increases fuel efficiency so much that it cuts the fuel bill to just $552 a year — a savings of $269 a year.’’

“The question, of course, is how to pay for … tangible improvements in public transit. The answer lies in getting the true beneficiaries of improved public transit to pay for it. If drivers were to pay only $269 a year more in gasoline taxes, tolls, or a vehicle miles traveled fee to the MBTA, the Commonwealth would have an additional $3 billion over 10 years to make some of these improvements.’’

Most other major industrialized nations, including our neighbor Canada, understand the big economic and social benefits of dense public-transit in their metro areas. Check out Toronto, for example. The United States, as usual the laggard in infrastructure (though it didn’t used to be this way), will pass an ever-steeper price for not addressing this issue, which profoundly affects the way so many of us live.

To read Bluestone’s piece, please hit this link.

Is it time to tear down some expressways, or bury them?

Boston's Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy Greenway (near the water in the foreground) now covers what had been the infamous surface version of the Central Artery, aka "The Distressway.''

-- Photo by Hellogreenway

A recent Sunday New York Times Style section (why the Style section?!) ran a story headlined “Exit the Expressway” (the headline has since been updated) about cities looking at tearing down some of those huge highways that were plowed through cities and parks in the construction heyday of the Interstate Highway System and states’ new-road projects.

In many towns and cities these highways rent the urban fabric, cutting off neighborhoods from each other even as they encouraged suburban sprawl. The Times’s story focuses on the Scajaquada (!) Expressway, aka New York State Route 198, in Buffalo. Its construction in the early ‘60s tore the lovely Delaware Park in half. Similar stuff happened in other cities during the orgasmic phase of the Automobile Age.

Now there’s a plan to convert at least part of the expressway into a lower-speed boulevard. It recalls proposals to turn the infamous 6/10 Connector in Providence into a boulevard.

Removing expressways has worked elsewhere, perhaps most successfully with downtown San Francisco’s Embarcadero Freeway, whose removal helped reenergize the city’s waterfront and led to a real-estate boom in the area.

Of course, another way to help repair the damage done to cities, and especially downtowns, by expressways is to put them underground, as was done with Boston’s infamous Central Artery in the Big Dig. The Central Artery’s roof is now a park. Unfortunately there’s far from enough money to a do a similar project with Route 95 in Providence, which creates a fearsome barrier through the middle of the city. But we can dream….

But what does seem likely is that changes in lifestyles, economics and environmental considerations will prevent a recurrence of the expressway- building boom of the ‘50s through the ‘70s. For one thing, we have a much stronger appreciation now of the need to preserve neighborhoods and to reduce our dependence on cars. Further, young people especially (say 35 and under) drive less than their parents and many of them much prefer cityscapes to suburbia; indeed they're turning parts of suburbia into places that look like walkable cities.

To read The Times’s article, please hit this link:

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/21/style/the-end-of-freeways.html