Raja Kamal/Arnold Podgorsky: Reform Judaism's lessons for Muslim immigrants

In a recent article in the Eurasia Review, Riad Kahwaji identified a troubling relationship between ISIS-inspired terrorist attacks and increasingly hostile reactions from nationalist and other right-wing parties across Europe. Muslim immigrants most often arrive in the West from Islamic countries beset by oppression, illiteracy and poverty, he notes. Western Muslim leaders have not effectively addressed these challenges, and resistance to assimilation by many in their communities has made them more vulnerable to extremism.

Among the factors that make integration into Western societies difficult for Muslim immigrants are the ways in which Islamic principles have been inculcated by parents and other elders; apparent biases concerning life in the West that have been influenced by government, political and religious propaganda in their countries of origin; and a lack of cultural empathy, common languages, and understanding of Western culture. In addition, Muslim communities in Europe are overly reliant upon imams recruited from abroad who are not overseen by an Islamic higher authority that sets standards of education and practice for the clerics.

Combine these factors with resistance from elements of the predominantly non-Muslim population, high unemployment rates among young Muslims and lack of opportunity for social and economic advancement, and it is easy to see why a significant minority of Muslim youths in Europe and certain U.S. communities are susceptible to radicalization. In France, about 10 percent of the population is Muslim, but 70 percent of the prison population is – and prison is the single most fertile ground for recruitment of terrorists. Attacks by individuals and groups purporting to represent Islam not only alienate average citizens but also produce a furious backlash of anti-immigrant fervor on the part of right-wing political leaders and organizations.

To address the challenges faced by Muslim immigrants, it might be instructive to consider the lessons of the Judaic diaspora. After their destruction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem, in 70 A.D., the Romans expelled the Jewish people from the Holy Land. For centuries, Jews often lived separately from indigenous populations, gathering in tightly knit communities. Informed by suspicion of “the other” and often by outright antisemitism, what today would be called “host communities” frequently prohibited Jews from participating in most professions and crafts and in the political and cultural life of the societies. Sometimes, anti-Jewish attitudes were expressed violently, and attacks on Jewish people and their communities were not uncommon. Jewish separateness, whether voluntary or enforced, was essentially the norm.

By the end of the 18th Century Reform Judaism emerged in Germany and eventually in the U.S. The movement developed in part as an extension of the growth of rationalism in Western thought since the Enlightenment and in part as a reaction to the strictures and separateness that traditional Judaism demanded. The Reform movement (and, to a lesser extent, the movement for Conservative Judaism) advocated a relaxation of the more fundamental practices of traditional Judaism and greater assimilation into the economic, educational, and political mainstream of European societies. It welcomed modernity. In place of strict observance, Reform Judaism emphasized ethics, charity, and the admonition to “heal the world” as essentials of the Jewish character.

To bolster new ideals, an infrastructure of Jewish institutions and organizations evolved that not only served the needs of Jews but also interacted with similar structures in host societies. Among the new institutions that were most critical were seminaries that provided rigorous professional education for new generations of rabbis.

Over time, the threats of political oppression and violent antisemitism diminished in many places (not at all times or in all places, but generally). Progress was made in part because it was based on the long-established Judaic principle that Jews are to respect the laws of the lands they inhabit (except where they directly conflict with fundamental Jewish belief as, for instance, in the case of idol worship).

The Reform movement spawned contemporary Jewish pluralism, which now includes several streams of Jewish thought and practice. These diverse approaches provide an example of integration and response to evolving philosophical and political norms, while preserving essential and nourishing tenets of the Jewish faith. Adherents have managed to assimilate effectively into societies that are predominantly non-Jewish by adapting religious practice and expression to fit with the laws, culture and customs of their adoptive homelands.

Might the experience of the Jews in Western societies provide a model for the growing Muslim communities of Europe and North America? Perhaps so, but it is essential that reform in Islamic practice and custom be initiated and molded by leaders in those Muslim communities. We recognize that such efforts to reform will be met with resistance, but success is possible if all remember that, in our diverse communities, we can only embrace the ways of peace by respecting and making room for each other – and, in matters of faith, there is always more than one path up the mountain.

Raja Kamal is senior vice president of the Buck Institute for Research on Aging; based in Novato, Calif. Arnold Podgorsky is a lawyer and former president of Adas Israel Congregation in Washington, DC, a Conservative synagogue.

Peter Certo: Americans' absurd exaggeration of the terror threat against them

Via otherwords.org

One in 3.5 million: That’s the risk you’ll die from a terrorist attack in the United States, Ohio State Prof. John Mueller estimates. Rounded generously, that chance comes to 3 one-hundred thousandths of a percent.

That’s not how most Americans see it, though.

In a recent Gallup poll, 51 percent of respondents said they’re personally worried about becoming a victim. If you’ll forgive my amateur number crunching, that means we’re overestimating the terrorist threat by factor of about 1.7 million.

No wonder people play the lottery.

Meanwhile, Barack Obama is trying hard — with mixed results — not to get pushed into another Middle Eastern war. But that’s a tall order when Americans are more fearful of attacks than at any time since 9/11 — and when politicians like Ted Cruz are calling for bona fide war crimes like “carpet-bombing” Syria.

Obama tried hard to walk that line in his final State of the Union address.

He dismissed critics who likened the fight against the Islamic State to “World War III,” and insisted (correctly) that the group poses no existential threat to the United States. But he also assured listeners that the militants would be “rooted out, hunted down, and destroyed.”

To that end, Obama boasted, American planes had already launched 10,000 airstrikes on Iraq and Syria.

This appeal to the carpet-bombing constituency was Obama’s attempt to break the political taboo against counseling modesty about the threat of terrorism. Unfortunately, it only illustrates a much deeper taboo against admitting that foreign terrorism against our country is almost always a response to our foreign policies.

You know, policies like launching 10,000 airstrikes.

Political scientist Robert Pape should know. He’s studied every suicide attack on record.

Pape argues that while religious appeals — Islamic or otherwise — can help recruit suicide bombers, virtually all attacks can be reduced to political motives. “What 95 percent of all suicide attacks have in common,” he concludes, “is not religion.” Instead, there’s “a specific strategic motivation to respond to a military intervention.”

In the years before al-Qaida pulled off the 9/11 attacks, for instance — and since, for that matter — Washington propped up repressive regimes in places like Saudi Arabia and Egypt, which ruthlessly subjugated Islamist and liberal challengers alike. It armed and enabled Israel, even as the country bombed its Muslim (and Christian) neighbors in Palestine and Lebanon.

And in between its two full-scale invasions of Iraq, Washington imposed devastating sanctions that caused well over half a million Iraqi children to die from a lack of food or medicine.

In his letter explaining the 9/11 attacks, Osama bin Laden mentioned all of these things and more to argue that U.S. intervention in the Muslim world had to be stopped. That’s an opinion shared by plenty of people who aren’t mass murderers.

Similarly, before it expanded to Syria, the infamous Islamic State emerged out of a Sunni rebellion against the repressive Shiite government Washington set up in Iraq after toppling Saddam Hussein. To the extent that it’s engaged in international terrorism, ISIS has mostly targeted countries — like France, Turkey, Lebanon, and Russia — that have plunged into Syria on the side of its enemies.

None of this excuses terrorism in the least. But it strongly suggests that senseless wars only increase the risk of attack — especially when there’s not a bomb on this planet (much less 10,000 of them) powerful enough to put Iraq and Syria back together. Diplomats may do that someday. Carpet-bombing won’t.

Until then, a 0.00003 percent risk of terrorism is high enough. Why multiply it by acting rashly?

Peter Certo is the editor of Foreign Policy In Focus and the deputy editor of OtherWords at the Institute for Policy Studies. IPS-dc.org

Back home, under wraps

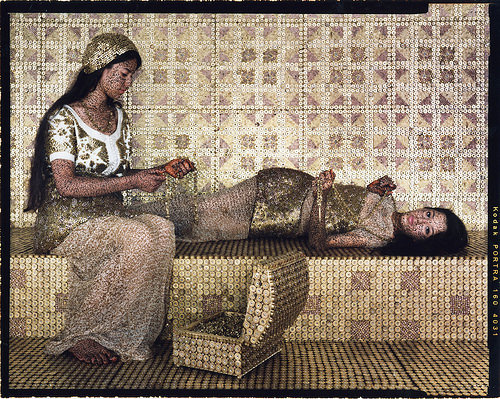

"Bullets Revisited #8'' (C-41 photographic print mounted on aluminum), by LALLA ESSAYDI, in the show "Beyond the Veil,'' at the University of Massachusetts at Lowell, through March 20.

The gallery says the show "explores the complexities of Arab female identity, both from an insider's experience of her own Moroccan childhood, and with the outsider perspective of a Western-trained artist.''

The pictures are part of a "collaborative performance project that takes place in her childhood home in Morocco with female friends and family members.''

"{T}hese women use calligraphy, bullet casings, henna, their bodies and their gaze to subvert traditional and imposed notions of gender, ethnicity and identity.''

She's lucky to have escaped, at least in part, Arab culture, with its often horrendous treatment of women and of members of other religions faced with the brutal bigotry of some versions of Islam. She now lives relatively safely in the U.S., away from 7th Century ideas of women's place in the world.