Brown University’s big ambitions for cancer center

Rhode Island Hospital, in Providence, is the flagship institution of the Brown University-affiliated Lifespan hospital chain.

— Photo by by Kenneth C. Zirkel

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

“Brown University has partnered with a local hospital chain with the goal of establishing a state-of-the art cancer-research center in Rhode Island. The university’s research branch has partnered with Lifespan Cancer Institute’s clinical care, with the eventual goal of applying for a National Cancer Institute designation. Such a designation would allow for further funding and increase the type and amount of clinical trials the research institute could conduct.

“Dr. Wafik El-Deiry, the director of the Cancer Center at Brown University, recently spoke to The Boston Globe about his excitement for the development of this program at the university. ‘There really wasn’t too much development yet before [the center] at Brown because there was no story,’ he said. ‘There wasn’t a program… to really make a difference and get to where we need to go, we have to grow. We need to recruit, we need space, and we need resources. And now, with Brown’s support, all of that is really coming together,’ he told The Globe.

“As this program grows, there is optimism that Rhode Island could become a prime cancer-care destination. The program is expected to soon start attracting brilliant individuals who seek to advance the future of medicine and cancer care. This program aims to establish the Ocean State a top location for research, learning, and care.’’

More efficient and more expensive?

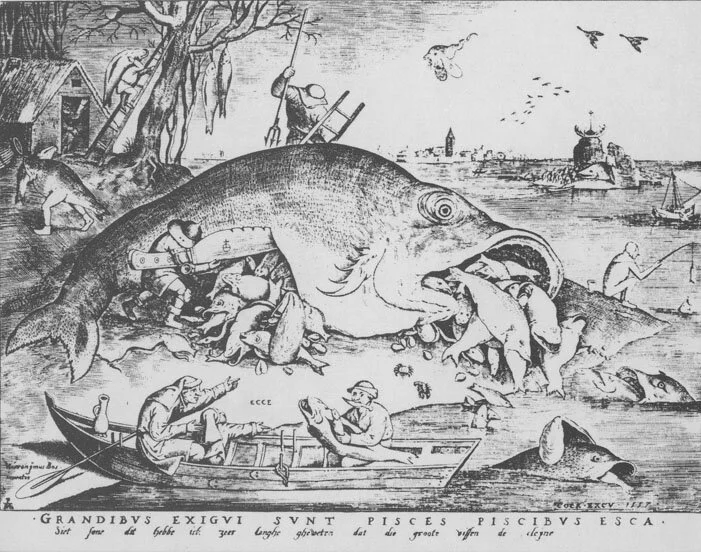

“The Big Fish Eat the Small Ones,’’ by Peter Brueghel the Elder (1556).

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

“The sooner patients can be removed from the depressing influence of general hospital life the more rapid their convalescence.’’

-- Charles H. Mayo, M.D. (1865-1939), American physician and a co-founder of the Mayo Clinic, in Rochester, Minn.

The plan for Lifespan and Care New England (CNE) to merge, if regulators approve it, would probably make Rhode Island health care more efficient. It would do this through integrating their hospitals and other units. That would do such things as speeding the sharing of patient information among health-care professionals and streamlining billing. Further, it would probably strengthen medical research and education in the state, much of it through the new enterprise’s very close links with the Alpert Medical School at Brown University, which, indeed, has pledged to provide at least $125 million over five years to help develop an “academic health system’’ as part of the merger.

The deal, by reducing some red tape (with the state having just one big system instead of two), might make health care in our region more user-friendly for patients, dissuading more of them from going to Boston’s world-renowned medical institutions, thus keeping more of their money here.

The best example of where the merger could improve health care would be in better connecting Lifespan’s Hasbro Children’s Hospital with Care New England’s Bradley Hospital, a psychiatric institution for children, and Women & Infants Hospital.

But would the huge (especially for such a tiny state) new institution have such power that it would impose much higher prices? Studies have shown that hospital mergers almost inevitably mean higher prices. So insurance companies, as well as poorly insured patients, may eye a Lifespan-CNE merger with trepidation.

And expect job losses, at least for a while, given the need to eliminate the administrative redundancies created by mergers. Meanwhile, senior- executive salaries in the new entity would probably be even more stratospheric than they are now at the separate “nonprofit” companies, and I imagine the golden parachutes for departing excess senior execs would blot out the sun.

Meanwhile, Boston will remain a magnet for health care, and so it’s conceivable that the behemoth and very prestigious Mass General Brigham hospital group would end up absorbing the Lifespan-CNE giant in the end anyway.

Health-care behemoth coming for a tiny state?

Behemoth as depicted in the Dictionnaire Infernal

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Good out of bad? Lifespan and Care New England, Rhode Island’s two big “nonprofit’’ hospital systems, have had to tightly coordinate their responses to the COVID-19 crisis – an experience that has led them to revive merger or at least “collaboration’’ plans. A merger might save on administrative and other costs borne by the public and enable the state to have a system big and strong enough to compete with the Boston health-care behemoth by maintaining a full-range of medical services and research in the Ocean State and by strengthening its only schools of medicine and public health, at Brown University. A merger might preserve a lot of jobs in Rhode Island. But at the same time, many jobs would presumably be lost as the merged company eliminated redundancies.

Of course, such a large and powerful merged entity would have to be carefully regulated. As Michael Fine, M.D., warned last week in GoLocal, such mergers have tended to raise health-care consumers’ costs because of the monopoly pricing-power created. And I wonder what gigantic golden parachutes, paid for indirectly by the public, would go to Lifespan and Care New England senior executives in a merger.

To read Dr. Fine’s comments, please hit this link.

Boston gobbling up Providence

The Warren Alpert Medical School at Brown University, in Providence's old Jewelry District. The building used to be a factory.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb's "Digital Diary,'' in GoLocal24.com

Brown University says it will continue its links with Care New England (CNE), which has medical school teaching hospitals, even if Boston-based behemoth Partners HealthCare takes it over. Well, of course Brown would have to: It needs nearby teaching hospitals!

The PR on this is that the medical school would remain Care New England’s primary research and teaching affiliate. Well, maybe. The financial and research clout of Partners (with such world-renowned hospitals as Massachusetts General and Brigham and Women’s hospitals) is such that that we can expect a lot of CNE stuff now being done in Rhode Island – much of it administrative but some of it clinical work and research -- will end up being done in Boston. A lot of jobs will disappear around here, but some might be added, too, maybe even from Boston:

Greater Providence will continue to have the advantages of being a cheaper and easier place to work in.

Next stop: Partners might also buy Lifespan, the biggest Rhode Island hospital system, thus becoming a statewide monopoly. An alluring opportunity to jack up prices.

Boston sucking in the health-care biz; better trains, please

Main entrance of Massachusetts General Hospital, in Boston. MGH is the flagship of Partners HealthCare.

It’s unclear what precisely is going on with the new talks among Partners HealthCare, the giant Boston-based hospital system, and Rhode Island’s Care New England (CNE) and Lifespan. Partners of course has been trying to take over CNE, and now it may be trying to take over Lifespan, too. The participants’ statement that they are assessing how “they might work together to strengthen patient care delivered in Rhode Island’’ is smoke that may camouflage what might really be going on: a plan for Partners to take over most of the Ocean State’s hospitals. (Who knows what might happen with South County Hospital, which is still independent. Westerly Hospital is part of the Yale New Haven Health System.)

The effect of a takeover by Partners would be that much (most?) of Rhode Island’s health care would be run from Boston, one of the most important medical centers on Earth. It would mean that, more and more, complex procedures for Rhode Islanders’ very serious illnesses and injuries would be performed in Boston, because of the efficiencies of scale and the density of specialists there, and not in Rhode Island, which would offer mostly primary and behavioral- and mental-health care.

It’s unclear what the impact would be on the Brown Medical School. Butler, Bradley, Hasbro Children’s, Miriam, Rhode Island and Women & Infants’ hospitals, as well as the VA Medical Center in Providence, are all teaching institutions for Brown. Partners’ facilities are teaching hospitals for the behemoth Harvard Medical School. Tough competition.

A Partners takeover of CNE and Lifespan, besides providing very lucrative golden parachutes for CNE and Lifespan executives – bosses of enterprises being acquired love mergers because they make a personal killing -- would leave an enterprise with huge pricing power. You can be pretty sure that it would take full advantage of this by jacking up prices, just as Partners has done in Greater Boston. That has drawn much scrutiny from Massachusetts regulators and long investigative pieces from The Boston Globe.

Rich and powerful Greater Boston often seems to suck up a lot of oxygen in New England. Still, overall, Rhode Island benefits from being so close to a world city, with its massive wealth creation and cultural richness. Indeed northern Rhode Island is increasingly part of Greater Boston – a cheaper residential and workplace option for people who need to be close to, especially, downtown Boston/Cambridge. Consider that Rhode Islanders will soon be able to apply for some of the 2,000 jobs that the increasingly monopolistic Amazon has just announced it will add in Boston, which is also still a candidate for the company’s much-hyped “second headquarters.’’ (Will the massive coastal flooding that seems to be an increasing threat to Boston’s Seaport District scare them away?)

The improvements in Boston-Providence MBTA commuter rail service promoted by a group called TransitMatters would improve the benefits to Greater Providence of being close to Boston. Few if any projects enrich a metro area like good mass transit.

To read the TransitMatters.org on this, please hit this link:

http://transitmatters.org/regional-rail-doc

Among the organization’s many recommendations is for trains on the Boston-Providence line to run every 15 minutes at peak times and every half hour in off-peak times, as well as free transfers among commuter trains, buses and subways. The aim is also to cut the MBTA train time between Providence and South Station, in Boston, by, say 20 to 25 minutes.

This may all seem pie in the sky until you see that Europe and East Asia already have such service – actually, some of it is even better. A major reason is that they see state-of-the-art passenger train service as crucial for the socio-economic health of their metro regions and are willing to levy the taxes needed to provide it, unlike in private-opulence-public-squalor America.

R.I. hospitals pulled north and south

From Robert Whitcomb's "Digital Diary'' in GoLocal24.com:

So South County Hospital and Yale New Haven Health System are discussing linking up, presumably along the lines of what the Connecticut institution has already done with Westerly Hospital. It’s another reminder of how Rhode Island is being more and more absorbed into multi-state markets. From, say, East Greenwich north, the Ocean State is more and more part of Greater Boston. From East Greenwich to the southwest, it’s drawn into the coastal Connecticut/metro New York orbit.

Rhode Island can be a less expensive, more convenient and physically attractive alternative to those more congested and expensive places. While the state’s hospitals might not be able to offer the full range of services available at some famous Boston or New York hospitals or at Yale New Haven, they can provide most of the services that patients need. Meanwhile, Rhode Island could become a national model for primary care, helped by the Alpert Medical School at Brown’s nationally known primary-care training.

And there’s no reason that an out-of-state organization, such as Yale New Haven, for one, would close down certain highly profitable specialty services in Rhode Island, such as South County Hospital’s joint-replacement program.

There are many social and economic advantages to being between two of the richest and most important cities in America. And the more the Ocean State gets absorbed into the big metro areas to its north and south, the less provincial and tribal it will be.

Timothy J. Babineau, M.D.: Study what works well in U.S. healthcare and build on it

American healthcare is expensive. Too expensive. On this, there is little debate. In 2001 the median U.S. household spent 6.4 percent of its income on healthcare; by 2016, the same household spent 15.6 percent of its income on healthcare. That bigger share of the pie leaves less for other essential purchases such as food, education and housing.

The same phenomenon exists at the national level, with spending on education, the environment and social programs getting squeezed. Recent estimates from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) have the American healthcare tab coming in at $3.6 trillion for 2016 and projected to continue to soar through 2025. Despite broad agreement that rising healthcare costs are unsustainable, the root causes of the rates of increase and the best ways to combat them remain the subject of some debate and confusion.

Numbers matter. The 80/20 rule—known to healthcare actuaries as the Pareto principle, posits that 80 percent of all medical spending is incurred by only 20 percent of the population. Whether a population is defined as a company, a county, or a country, most healthcare spending is for care of a small minority of individuals. Moreover, the bulk of that spending arises from either largely unavoidable or unpredictable single events (such as trauma or sudden-onset acute illnesses); such chronic conditions such as diabetes; complex episodes of care for such illnesss as cancer, and care delivered at the end of life.

A critical (but often overlooked) point is the fact that as much as 40 percent of spending during chronic and complex episodes is avoidable if providers and systems adhere to established standards of care. Reining in runaway healthcare spending must involve better management of high-cost episodes of chronic and complex care.

A key buzzword in today’s debate is “population health”. Confusion occurs when the term is interpreted as a strategy for controlling healthcare costs when it is applied across our entire population as opposed to the sickest 10 percent or 20 Percent. Wellness initiatives, early detection, the avoidance of emergency room visits, and disease prevention have undeniable value, and should all be pursued, but they will not (by themselves) sufficiently reduce healthcare spending by enough to make the system “affordable”.

As the Baby Boomers swell the ranks of Medicare beneficiaries, the inevitability of illness is the only certainty in an otherwise uncertain world. To be successful, programs, payment systemsand policies to curb healthcare spending must focus on improving the efficiency and effectiveness of care delivered to the sickest subset of the population. This is best accomplished within a completely integrated healthcare-delivery system.

American hospitals and healthcare systems are among the best in the world. Rather than asserting that “American healthcare is broken” and in need of rebuilding from scratch, a better strategy may be to look at what works well within our system and ask how we can build on those strengths while facing the escalating costs head on. Hospital systems are in the health care business, and we should not be reluctant to say so. No matter what wellness and prevention programs we collectively offer, inevitably a small subset of the population will still get very sick, and it is a core mission of health systems—working in close partnership with our primary and specialty providers—to take the very best and most efficient care of them when that happens.

Irrespective of what happens with the Affordable Care Act (ACA), as leaders in health care, we must redouble our efforts to eliminate unnecessary variations and wasteful spending in the clinical care we deliver to patients.

Rather than debate the actual percentage that is “wasteful spending” (now commonly referenced at around 30 percent) we would be better served by continuing the hard work of identifying and eliminating areas within our own systems where needless variations in care add cost without improving outcomes. As Lifespan, the system I lead, continues to evolve into a comprehensive, high-value, integrated healthcare system, we are doing just that.

Timothy J. Babineau, M.D., is president and chief executive of Providence-based Lifespan, a large hospital system, and a professor of surgery at the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University.

Robert Whitcomb: How to Speed Up Infrastructure Repair

An irritated citizenry has blocked a bid by the Pawtucket Red Sox, employing very few people and with a mostly seasonal business, to grab valuable public land and erect, with lots of public money, a stadium in downtown Providence, on Route 195- relocation land. The plan would have involved massive tax breaks for the rich PawSox folks that would have been offset by mostly poorer people’s taxes.

The public is belatedly becoming more skeptical about subsidizing individual businesses. (Now if only they were more skeptical about casinos’ “economic- development’’ claims. Look at the research.)

Perhaps Lifespan will sell its Victory Plating tract to the PawSox. And maybe a for-profit (Tenet?) or “nonprofit’’ (Partners?) hospital chain will buy Lifespan, which faces many challenges. Capitalism churns on!

In any event, the stadium experience is a reminder that we must improve our physical infrastructure, in downtown Providence and around America.

Improved infrastructure will be key to a very promising proposal by a team comprising Baltimore’s Wexford Science & Technology and Boston’s CV Properties LLC for a life-sciences park on some Route 195-relocation acres. This could mean a total of hundreds of well-paying, year-round jobs in Providence at many companies. Tax incentives for this idea have merit. (I’d also rather fill the land slated for a park in the 195 area with other job-and-tax-producing businesses, but that’s politically incorrect.)

The proximity of the Alpert Medical School at Brown University, the Brown School of Public Health, hospitals and a nursing school is a big lure. Also attractive is that Providence costs are lower than in such bio-tech centers as Boston-Cambridge and that the site is on the East Coast’s main street (Route 95, Amtrak and an easy-to-access airport).

Rhode Island’s decrepit bridges and roads are not a lure. Governor Raimondo’s proposal for tolls on trucks (which do 90 percent of the damage to our roads and bridges) to help pay for their repair, and in some cases replacement, should have been enacted last spring. It’s an emergency.

It takes far too long to fix infrastructure, be it transportation, electricity, water supply or other key things. The main impediment is red tape, of which the U.S. has more than other developed nations. That’s why their infrastructure is in much better shape than ours.

Common Good sent me a report detailing the vast cost of the delays in fixing our infrastructure and giving proposals on what to do. It has received bi-partisan applause. But will officials act?

The study focuses on federal regulation, but has much resonance for state policies, too. And, of course, many big projects, including the Route 195-relocation one, heavily involve state and federal laws and regulations.

Among the report’s suggestions:

* Solicit public comment on projects before (my emphasis) formal plans are announced as well as through the review process to cut down on the need to revise so much at the end, but keep windy public meetings to a minimum.

* Designate one (my emphasis) environmental official to determine the scope and adequacy of an environmental review in order to slice away at the extreme layering of the review process. Keep the reports at fewer than 300 pages. The review “should focus on material issues of impact and possible alternatives, not endless details.’’ Most importantly, “Net overall (my emphasis) impact should be the most important finding.’’

* Require all claims challenging a project to be brought within 90 days of issuing federal permits.

* Replace multiple permitting with a “one-stop shop.’’ We desperately need to consolidate the approval process.

Amidst the migrants flooding Europe will be a few ISIS types. That there are far too many migrants for border officials to do thorough background checks on is scary.

Fall’s earlier nightfalls remind us of speeding time. When you’re young, three decades seem close to infinity, now it seems yesterday and tomorrow. I grew up in a house built in 1930, but it seemed ancient. (My four siblings and I did a lot of damage!) Yet in 1960, when I was 13, the full onset of the Depression was only 30 years before. The telescoping of time.