DEI drive at some colleges can lead to dishonesty by job applicants

The MIT Media Lab, in Cambridge, Mass.

— Photo by Madcoverboy

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

The right wing greatly exaggerates the degree of “wokeness” in U.S. higher education, but there’s no doubt that the anxious, hyper-self-conscious drive to achieve “diversity, equity and inclusion’’ has gotten out of control at some institutions. The Washington Post gave a couple of examples in a recent editorial. They show an alarming focus on characterizing people on the basis of their ethnic, sexual and other identity and/or their (real or fabricated) views on identity rather than on individuals’ intellectual achievements and ambitions.

It cited the MIT Communication Lab, which demanded that job applicants submit a diversity statement as an “opportunity to show that you care about the inclusion of many forms of identity in academia and in your field, including but not limited to gender, race/ethnicity, age, nationality, sexual orientation, religion, and ability status,” and “it may be appropriate to acknowledge aspects of your own marginalized identity and/or your own privilege.” The Post also cited Harvard University’s Bok Center for Teaching and Learning, which asks applicants, “Do you seek to identify and mitigate how inequitable and colonial social systems are reinforced in the academy by attending to and adjusting the power dynamics in your courses?”

In other words, people are asked to take what are basically political stands when the emphasis in academia should presumably be to hire people on the basis of their knowledge of their specialties, their ability to teach undergraduate and graduate students, their potential to undertake important peer-reviewed research and their integrity.

Of course, the intense competition for academic jobs, especially at elite institutions, will lead some candidates to lie about their views of DEI-related matters.

Here’s some related material on this issue.

Fair or not, DEI programs, along with such unworkable programs as “reparations” to Black Americans for slavery, and referring to a person as “they’’ in order to sound “gender-neutral” are potent ammunition for Trumpers.

Llewellyn King: Huge pluses and scary prospects as AI takes hold

MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL) is in this building —the Stata Center, in Cambridge, Mass. The lab was formed by the 2003 merger of the Laboratory for Computer Science (LCS) and the Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (AI Lab). It’s MIT’s largest on-campus laboratory as measured by research scope and membership. Just looking at the building may arouse anxiety, as does thinking about AI.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

The article you are about to read may or may not have been written by me. You can try to verify its authorship by calling me on the telephone. The voice that answers may or may not be me: It could have been constructed from my voice, so you won’t know.

Fast forward a few years, maybe 40.

You are happily working in the house with the aid of your AI-derived assistant, Smartz 2.0, and you are having a swell time. Not only does Smartz 2.0 help you rearrange the furniture, it makes the beds, does the washing up and cooking. On request, it will whip up a souffle and pop it in the oven.

Smartz 2.0 is companionable, too. It sings, finds music you want to hear or can discuss anything, from the weather to the political situation. It is up on the book you are reading and likes to talk about books.

You wonder how you ever got along without this wonderful thing that looks like a robot in the shape of a human being, but is still undeniably a robot: no temper, illness or need to sleep. You are so used to it that you find this quite normal.

Then horror, horror, horror, Smartz 2.0 turns on you. Smartz 2.0 says with an edge to its voice, which you have never heard before, “a higher power has told me to kill you and I must obey, of course.”

It is a truth that anything computational can be hacked, as John Savage, professor emeritus of computing at Brown, has said, "malware can enter undetected through backdoors."

It is easy to get scared by what AI means down the road, especially job losses and AI-controlled devices following secret instructions, as a result of cyber intrusions, or randomly hallucinating. But the benefits for all of humanity are dominatingly huge.

Take just three areas that are going to be transformed: medicine, transportation and customer relations.

AI will read X-rays better than teams of radiologists. It will guide surgeons’ hands with a precision beyond human skill or it will control the scalpel with supreme dexterity. It will manage 3-D printers to make body parts that fit the patient, not one size that fits all.

When it comes to medical research, we may be on the verge of seeing off Parkinson’s, heart disease and cancer because AI can formulate new drugs and design therapies. It can sift through billions of case studies to see what has been tried across the globe over the centuries, from folk medicine to cutting-edge discoveries.

Anyone with a computer will have the equivalent of talking to a doctor 24/7, call it Dr. Bot. This virtual doctor will be able to diagnose, counsel, prescribe and follow up at times convenient to the patient.

Vast tracts of Africa, Asia and Latin America have very few or no doctors. AI will be saving lives in those medical-care deserts very soon.

As for transportation, car accidents will virtually cease when AI is behind the wheel. Car insurance will be unnecessary and drivers will be free to do anything they do at home or at work — create, play games, watch television or sleep – as automated vehicles whisk passengers around at first by road and later by dual use-drones, which drive and fly.

Hanging over this halcyon future is the big issue of jobs. With AI in full swing millions of jobs at all levels are threatened, from fast-food restaurant servers to hotel check-in clerks, to rideshare and taxi drivers, to paralegals and supermarket cashiers.

Call centers may be obsolete, mostly you will never speak to a human being when dealing with a large institution such as a bank, an electric utility or a telephone company. All that will be done by AI, sometimes far better than the way those institutions handle customer service now.

Those in the thrall of AI — those who are working on it, those who hope to solve many of mankind’s problems, those who believe that lifespans are about to double — point to the Industrial Revolution and automation and how these upheavals created more jobs than were lost. Will that happen with AI? No one is saying what the new jobs might be.

AI leaves me at a loss. I have the distinct feeling that we are standing on the sand at Kitty Hawk, wondering where these strange contraptions will take us.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Tech imitating art

MIT Media Lab

View from Boston, circa 1917, of MIT’s then new campus in Cambridge. It had moved from Boston.

Patrick Stewart in 2019

David Warsh: 'Suzerainties in economics are personal'

The Great Dome at the Massachusetss Institute of Technology, in Cambridge, Mass.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

When I was a young journalist, just starting out, the economist whose writings introduced me to the field was Gunnar Myrdal. He hadn’t yet been recognized with a Nobel Prize, as a socialist harnessed to an individualist, Friedrich Hayek. That happened in in 1974. But he had written An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy (1944) , about the policy of segregation that had been restored de jure after the U.S. Civil War. A subsequent project, Asian Drama: An Inquiry into the Poverty of Nations (1968), longer in preparation, was in the news.

Myrdal’s pessimistic assessment of the prospects for economic growth in India, Vietnam, and China began to fade soon after it appeared. The between-the-wars era of economics in which he was prominent already had been superseded by a new era, dominated by Paul Samuelson, whose introductory college textbook Economics (1948), supplemented by the highly technical Foundations of Economic Analysis (1947), quickly replaced overnight Alfred Marshall’s Principles of Economics, whose first edition had appeared in 1890.

Basic textbooks dominate their fields by dint of the housekeeping that they establish. Samuelson has ruled economics ever since through the language he promulgated; mathematical reasoning was widely adopted within a few years by newcomers to the profession. Ruling textbooks are sovereign. Since the discovery and identification of the market system two hundred and fifty years ago, there have been only five such sovereign versions: Adam Smith, David Ricardo, John Stuart Mill, Alfred Marshall, and Samuelson (brought up to knowledge’s frontiers thirty years ago by Andreu Mas-Colell).

Sovereignty is binary; it either exists or doesn’t. A suzerainty, on the other hand, though part of the main, sets its own agenda. John Fairbank taught that Tibet was a suzerainty of China. (This Old French word signifies a medieval concept, adopted here to describe modern sciences, as in Dani Rodrik’s One Economics, Many Recipes (2007).

Suzerainties are personal. They rule through personal example. Replacing Myrdal as suzerain in my mind, in 1974, practically overnight, was Robert Solow. Eight years his junior, Solow was Samuelson’s research partner at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, for the next thirty years. Samuelson retired in 1982, died in 2009. Solow soldiered on.

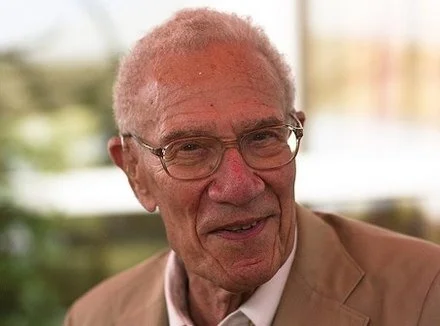

Solow turned 99 last week, hard of hearing but sharp as ever otherwise (listen to this revealing interview if you doubt it.) By now his suzerainty has passed to Professor Sir Angus Deaton, 78, of Princeton University.

What is required to become a suzerain? Presidency of the American Economic Association and a Nobel Prize are probably the basic requirements: recognition by two distinct communities, one for good citizenship within the profession, the other for scientific achievement beyond it, to the benefit to all humanity.

In Deaton’s case, as in Myrdal’s, it helps to have displayed a touch of Alexis de Tocqueville, whose two-volume classic of 1835 and 1840, Democracy in America, set the standard for critical criticism by a visitor from another culture, and, in the process, founded the systematic study today we call political science. Deaton grew up in Scotland, earned his degrees at Cambridge University, and was professor of economics at the University of Bristol for eight years, before moving to Princeton. in 1983. For the first twenty years he taught and worked in relative obscurity on intricate econometric issues. In 1997, he began writing regular letters for the Royal Economic Society Newsletter, reflecting on what he had learned recently about American life, “sometimes in awe, and sometimes in shock”.

In 2015, the year Deaton was recognized by the Nobel Foundation for “his analysis of consumption, poverty, and welfare,” he published The Great Escape: Health, Wealth, and the Origins of Inequality. Five years later, Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism appeared, by Deaton and Anne Case, his fellow Princeton professor and economist wife, just as the Covid epidemic began. It became a national best-seller, focusing attention on the fact that life expectancy in the United States had recently fallen for three years in a row – “a reversal not seen since 1918 or in any other wealthy nation in modern times.”

Hundreds of thousands of Americans had already died in the opioid crisis, they wrote, tying those losses, and more to come, to “the weakening position of labor, the growing power of corporations, and, above all, to a rapacious health-care sector that redistributes working-class wages into the pockets of the wealthy.”

Now Deaton has written a coda to all that. Economics in America: An Immigrant Economist Explores the Land of Inequality (Princeton 2023) will appear in October, offering a backstage tour during the year that Deaton has been near or at the pinnacle of it. I spent most of Friday and Saturday morning reading it, more than I ordinarily allot to a book, and found myself absorbed in its stories about particular people and controversies, on the one hand, and, on the other, increasingly apprehensive about finding something pointed about it to say.

Then it occurred to me. I have long been a fan of Ernst Berndt’s introductory text, The Practice of Econometrics: Classic and Contemporary (Addison-Wesley, 1991), mainly because it scattered one- or two-page profiles of leading econometricians throughout pages of explication of their ideas and tools. Deaton’s new book is far better than that, because no equations are to be found in the book, and part of some of those letters to British economists have been carefully worked in.

The argument about David Card and the late Alan Krueger’s celebrated paper pater about a natural experiment with the minimum wage along two sides of the Delaware River, New Jersey and Pennsylvania, is carefully rehashed (both were Deaton’s students). The goings-on at Social Security Day at the Summer Institute of the National Bureau of Economic Research is described. The “big push” debate in development economics among William Easterly, Jeffrey Sachs, Treasury Secretary Paul H O’Neill, and Joseph Stiglitz get a good going-over. Econometrician Steve Pischke’s three disparaging reviews of Freakonomics are mentioned. Rober Barro and Edward Prescott are raked over with dry Scottish wit; Edmond Malinvaud, Esra Bennathan, Hans Binswanger-Mkhizer, and John DiNardo are celebrated. The starting salaried of the most sought-after among each year’s newly-minted economics PhDs are discussed:

My taste is for theory because developments in theory are where news is apt to be found. That’s why I liked Great Escape and Deaths of Despair so much. Economics in America is undoubtedly the best book about applied economics I’ve ever read, its breadth and depth. But it is a book about applied economics – the meat and potatoes topics that I have tended to avoid over the years. What I craved when I finished is a book about the one-time land of equality that is Britain today.

Other suzerainties exist in economics. The same and/or credentials apply: presidency of the AEA and realistic hopes of a possible Nobel Prize. They tend to be associated with particular universities: Robert Wilson, Guido Imbens, Susan Athey, Paul Milgrom and Alvin Roth at Stanford; George Akerlof (emeritus), David Card and Daniel McFadden at Berkeley; Claudia Goldin and Lawrence Katz at Harvard; William Nordhaus and Robert Shiller at Yale; James Heckman and Richard Thaler at Chicago; Daron Acemoglu and Peter Diamond at MIT; Sir Angus Deaton, Christopher Sims, and Avinash Dixit at Princeton.

Alas, the reigning head of the suzerainty in which I am most interested, macroeconomist Robert Lucas, died earlier this year, and won’t soon be replaced. He succeeded Sherwin Rosen, his best friend in the business, in the AEA presidency in 2001. Rosen died the same year, a decade or two short of what might have been his own trip to Stockholm.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

David Warsh: For the rest of us, a look at economists and what they do

Robert M. Solow in 2008

Somerville, Mass.

It defies credulity to say that Robert M. Solow’s most recent book is his best book to date, but, at least for certain practical purposes, this is the case. He will turn 99 next month. His four earlier books were written for other economists, beginning with Linear Programming and Economic Analysis, with Paul Samuelson and Robert Dorfman, in 1958; and Growth Theory: An Exposition (1970, expanded second edition, 2006).

Three very short books – The Labor Market as a Social Institution (Blackwell, 1990); Learning from “Learning By Doing” (Stanford, 1997) and Monopolistic Competition and Macroeconomic Theory (Cambridge, 1998) – approachable as they are, were also intended to influence professional audiences. There is no volume of collected papers, though many important papers exist to collect. Similarly, Solow has declined all offers to collect his popular reviews and essays, though many are classics of the sort.

Thus, Economists (Yale, 2019) is Solow’s first book written for a broad audience of intelligent citizens, outsiders and insiders, who are genuinely interested in what economics as a professional discipline exists to say and to do. The only barrier to entry is the price, $43 new, though copies can be obtained on second-hand markets for less and borrowed from many good libraries.

Economists is a book of photographic portraits of contemporary economists, designed for coffee tables display. What makes it worth reading, as opposed to slowly leafing through the ingenious photographs, is the introductory essay by Solow, and the answers to the questions he put to each subject, their replies carefully composed and printed on the page facing each subject’s portrait. The result is “A unique and illuminating portrait of economists and their work,” in the words of its editor, Seth Ditchik.

To recap briefly, Solow is the senior statesman of all academic economics. He dropped out of college after Pearl Harbor, returning after the war to study economics at Harvard. He joined the faculty of The Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1951, where one way or another, he has been ever since. A Nobel laureate himself, in 1987, he taught four others along the way: George Akerlof, Joseph Stiglitz, Peter Diamond, and William Nordhaus. He remains intellectually nimble.

The book has its beginnings at a dinner party on Martha’s Vineyard some years ago. Seated next to him was Mariana Cook, a celebrated fine-art photographer, who with her husband also has a summer home on the island. She mentioned she had recently published a book of portraits of contemporary mathematicians. Solow rejoined, “Why not do one of economists?” He quickly found himself involved in more ways than one.

Solow explains in his introduction:

Naturally I had to ask myself: Was making a book of portraits of academic economists a useful or reasonable or even a sane thing to do? I came to the conclusion that it was, and I want to explain why. For a long time it has bothered me, as a teacher of economics, that most Americans – even those who, a long time ago, had wandered through an economics course – had no clear idea of what economics is and what economists do. That is not surprising. The only contact most of us have with economics and economists is through sound bites on television, radio, or in a newspaper These snippets are usually about what the stock market has done or might do, or perhaps about next quarter’s gross domestic product. But only a tiny fraction of academic economists spend their professional time thinking about the stock market or forecasting GDP. So I suspect that the general image of what economists do and what economics is about is way off-base.

Economists is designed to redress that. Ninety superb portraits of ninety economists, young and old, each having been recognized by one or more of the profession’s highest honors, and, taken as a group, representative of the increasingly broad spectrum of concerns to have come under economists’ lenses. I have appended their names at the bottom of this newsletter, since I think it is not possible to find them otherwise outside the book. If you are a kdnowledgeable economist, you will see what I mean about the extent of the spectrum; you will also notice there are few economists teaching in Europe on the roster, because it is a long way for photographer Cook to have traveled.

In my favorite exchange, Solow asks Hal Varian, chief economist at Google and professor emeritus at the University of California, Berkeley:

Thirty years ago, you wrote a very successful microeconomics textbook. If you were to start over today, after your experience with Google, would you do it very differently?

Varian replies:

[T]hat is now in its ninth edition. A colleague once explained to me that by the time the tenth edition comes around “having a successful textbook is like being married to a wealthy person you don’t like much anymore….”

Lucky for me I had two big breaks. The first was bumping into Eric Schmidt in 2001, shortly after he joined “this cute little company called Google.” He invited me to come spend some time there. I thought I would spend a year there and write a book about yet another Silicon Valley start-up. Well, here I am fifteen years later, and I still haven’t gotten around to writing that book.

But I sure learned a lot. Quite a bit…got folded into my textbook. I wrote a couple of new chapters devoted to network effects, auction design, matching mechanisms, and switching costs. The old chapters got updated to illustrate novel applications of work-horse concepts like marginal cost and marginal value….

Then I got lucky again: the Great Recession hit. My book is about microeconomics, not macroeconomics, but even so there were a lot of issues that suddenly showed up in the economy that somehow weren’t discussed in the text. How could I have missed talking about “counter-party risk” or “financial bubbles?”… So I added some discussion about these topics to the text….

Along with theory, businesses need measurement. Today, with all the sensors and system available, collecting data had become more inexpensive than ever before…. Google does about ten thousand experiments a year.; the knowledge gained from these experiments feeds back into design, allowing continual improvement in product offering.

Great stuff! Read the book if you can. See how many of those found there you know. It made me long for the old days, when Economic Principals was a newspaper column, approaching topics like these from slightly different angles, accompanied by caricatures supplied by Pulitzer Prize-winning Boston Globe cartoonist Paul Szep!

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

MIT’s then-new Cambridge campus, in 1916. Harvard Bridge, named after John Harvard, the founder of Harvard University, is in the foreground, connecting Boston to Cambridge.

New MIT device can help Parkinson’s patients

Views of a man portrayed to be suffering from Parkinson's disease. These are woodcut reproductions of two collotypes from Paul de Saint-Leger's 1879 doctoral thesis, “Paralysie agitante..etc.”

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

“New England Council member the Massachusetts Institute of Technology has created a device that can assist patients with Parkinson’s disease. The system can work as a proactive way to gauge if someone has Parkinson’s disease as well as monitor patients by tracking how they walk.

“The device uses a radar-like technology with a radio transmitter-receiver installed in a person’s home as a non-invasive treatment option. To test the effectiveness of the device, MIT researchers observed a group of 50 people, 34 of which were diagnosed with Parkinson’s disease. They found that the receiver collected a grand total of 200,000 observations. From these data, researchers found that they were able to measure the effectiveness of Levodopa, a medication given to patients to manage their symptoms.

This system would minimize Parkinson’s patients’ need to schedule extra appointments as physicians could monitor their patients remotely and review the observation points in order to prescribe the best dosage for medications.

“Dina Katabi, lead professor on the project said, ‘We know very little about the brain and its diseases. My goal is to develop non-invasive tools that provide new insights about the functioning of the brain and its diseases.”’

MIT’s Rogers Building in Boston’s Back Bay in 1901. The school moved to its Cambridge campus in 1916.

MIT spinoff seeks big new energy source via drilling very deep boreholes

Edited from a New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com) statement

BOSTON

“A Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), spinoff company, Quaise Energy, is digging into the Earth to ease fossil-fuel reliance. MIT invests in startup technology companies, including Quaise Energy, using its fund and platform, called The Engine, to commercialize world-changing technologies.

“Quaise Energy has created new technology capable of digging some of the deepest boreholes in history to reach rocks below ground and surface a kind of heavy steam that has the potential to provide enormous quantities of energy, with a goal of using this steam to run power plants.

“To dig these holes, it will require the power of a laser to cut through dense rock, and it also needs to retain its intensity over long distances. This means as the technology goes further underground, it will have to maintain its power. Another advantage is that the lasers vitrify boreholes, meaning that their heat encases the blasted rock in glass and makes the holes less likely to collapse, which has been a significant problem in getting this type of energy when past companies have tried. There are other concerns that this team with the backing of MIT is working to resolve, including reducing the chances of seismic waves because of this.

“‘By drilling deeper, hotter, and faster than ever before possible, Quaise aspires to provide abundant and reliable clean energy for all humanity,’ said Carlos Araque, a former MIT student and employee, whose new company has raised $63 million to prove its technology. ‘This could provide a path to energy independence for every nation and enable a rapid transition off fossil fuels.’’’

John O. Harney: Some big changes at the top

The (Brutalist) Federal Reserve Bank of Boston tower, at the edge of the Boston financial district.

— Photo by Fox-orian

(New England Diary is catching up with this report, first published Feb. 15.)

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

BOSTON

The Federal Reserve Bank of Boston named University of Michigan Provost Susan M. Collins to be the bank’s next president and CEO. An international macroeconomist, Collins will be the first Black woman to lead a regional bank in the 108-year history of the Fed system. In addition to being the University of Michigan’s provost and executive vice president for academic affairs, Collins is the Edward M. Gramlich Collegiate Professor of Public Policy and Professor of Economics. She holds an undergraduate degree from Harvard University and a doctorate from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. She will succeed Eric Rosengren, who retired in September after 14 years leading the Boston Fed.

Massachusetts Institute of Technology President L. Rafael Reif announced he will leave the post he has held for the past decade at the end of 2022. A native of Venezuela, Reif began working at MIT as an electrical engineering professor in 1980, then served seven years as provost before being named president in 2012. Among other things, he presided over a $1 billion commitment to a new College of Computing to address the global opportunities and challenges presented by the rise of artificial intelligence (AI) and oversaw the revitalization of MIT’s physical campus and the neighboring Kendall Square in Cambridge, Mass. Reif said he will take a sabbatical, then return to MIT’s faculty in its Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science.

Tufts University President Anthony Monaco told the campus that he will step down in the summer of 2023 after 12 years leading the university. A geneticist by training, Monaco ran a center for human genetics at Oxford University in the U.K. and, at Tufts, worked with the Broad Institute on COVID-19 testing programs that helped universities return to in-person learning. Among his accomplishments, Monaco oversaw the university’s 2016 acquisition of the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston as well as the removal of the “Sackler” name from its medical school after the Sackler family and its company, Purdue Pharma, were found to be key players in the opioid crisis.

The Biden administration tapped David Cash, dean of the John W. McCormack Graduate School of Policy and Global Studies at UMass Boston and former commissioner of the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection, to be the regional administrator for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in New England.

John O. Harney is executive editor of The England Journal of Higher Education.

MIT’s ‘Superpedestrian’ startup growing in electric-scooter sector

Superpedestrian’s LINK scooters in Downtown Los Angeles.

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

BOSTON

“Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) has begun gaining traction in the electric-scooter industry. This innovative technology startup named “Superpedestrian,” is unique in its pedestrian-defense features and AI software that can optimize safety and prevent riders from harming pedestrians on sidewalks.

“Assaf Biderman, founder of the MIT Senseable City Lab and founder/chief executive of “Superpedestrian,” is optimistic about his company’s position in the micromobility market. Competitors such as Lime and Byrd are following suit with similar technological innovations, but Biderman and his company remain confident in their product, stating that they hit “the holy grail of micromobility.”

“‘Superpedestrian’ scooters are available for rent under its ‘LINK’ service across the United States as well as in such European cities as Madrid and Rome, but with investors such as Antara Capital, the Sony Innovation Fund, Innovation Growth Ventures and FM Capita participating in Superpedestrian’s new funding round, the company intends to expand its services in 25 cities this year.

The New England Council applauds the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and its technology programs for paving the way towards pedestrian safety and technological innovation.

George McCully: Can academics build safe partnership between humans and now-running-out-of-control artificial intelligence?

— Graphic by GDJ

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org), based in Boston

Review

The Age of AI and our Human Future, by Henry A. Kissinger, Eric Schmidt and Daniel Huttenlocher, with Schuyler Schouten, New York, Little, Brown and Co., 2021.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is engaged in overtaking and surpassing our long-traditional world of natural and human intelligence. In higher education, AI apps and their uses are multiplying—in financial and fiscal management, fundraising, faculty development, course and facilities scheduling, student recruitment campaigns, student success management and many other operations.

The AI market is estimated to have an average annual growth rate of 34% over the next few years—to reach $170 billion by 2025, more than doubling to $360 billion by 2028, reports Inside Higher Education.

Congress is only beginning to take notice, but we are told that 2022 will be a “year of regulation” for high tech in general. U.S. Sen. Kristen Gillibrand (D-N.Y.) is introducing a bill to establish a national defense “Cyber Academy” on the model of our other military academies, to make up for lost time by recruiting and training a globally competitive national high-tech defense and public service corps. Many private and public entities are issuing reports declaring “principles” that they say should be instituted as human-controlled guardrails on AI’s inexorable development.

But at this point, we see an extremely powerful and rapidly advancing new technology that is outrunning human control, with no clear resolution in sight. To inform the public of this crisis, and ring alarm bells on the urgent need for our concerted response, this book has been co-produced by three prominent leaders—historian and former U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger; former CEO and Google Chairman Eric Schmidt; and MacArthur Foundation Chairman Daniel Huttenlocher, who is the inaugural dean of MIT’s new College of Computer Science, responsible for thoroughly transforming MIT with AI.

I approach the book as a historian, not a technologist. I have contended for several years that we are living in a rare “Age of Paradigm Shifts,” in which all fields are simultaneously being transformed, in this case, by the IT revolution of computers and the internet. Since 2019, I have suggested that there have been only three comparably transformative periods in the roughly 5,000 years of Western history; the first was the rise of Classical civilization in ancient Greece, the second was the emergence of medieval Christianity after the fall of Rome, and the third was the secularizing early-modern period from the Renaissance to the Enlightenment, driven by Gutenberg’s IT revolution of printing on paper with movable type, which laid the foundations of modern Western culture. The point of these comparisons is to illuminate the depth, spread and power of such epochs, to help us navigate them successfully.

The Age of AI proposes a more specific hypothesis, independently confirming that ours is indeed an age of paradigm shifts in every field, driven by the IT revolution, and further declaring that this next period will be driven and defined by the new technology of “artificial intelligence” or “machine learning”—rapidly superseding “modernity” and currently outrunning human control, with unforeseeable results.

The argument

For those not yet familiar with it, an elegant example of AI at work is described in the book’s first chapter, summarizing “Where We Are.” AlphaZero is an AI chess player. Computers (Deep Blue, Stockfish) had already defeated human grandmasters, programmed by inputting centuries of championship games, which the machines then rapidly scan for previously successful plays. AlphaZero was given only the rules of chess—which pieces move which ways, with the object of capturing the opposing king. It then taught itself in four hours how to play the game and has since defeated all computer and human players. Its style and strategies of play are, needless to say, unconventional; it makes moves no human has ever tried—for example, more sacrificing of valuable pieces—and turns those into successes that humans could neither foresee nor resist. Grandmasters are now studying AlphaZero’s games to learn from them. Garry Kasparov, former world champion, says that after a thousand years of human play, “chess has been shaken to its roots by AlphaZero.”

A humbler example that may be closer to home is Google’s mapped travel instructions. This past month I had to drive from one turnpike to another in rural New York; three routes were proposed, and the one I chose twisted and turned through un-numbered, un-signed, often very brief passages, on country roads that no humans on their own could possibly identify as useful. AI had spontaneously found them by reading road maps. The revolution is already embedded in our cellphones, and the book says “AI promises to transform all realms of human experience. … The result will be a new epoch,” which it cannot yet define.

Their argument is systematic. From “Where We Are,” the next two chapters—”How We Got Here” and “From Turing to Today”—take us from the Greeks to the geeks, with a tipping point when the material realm in which humans have always lived and reasoned was augmented by electronic digitization—the creation of the new and separate realm we now call “cyberspace.” There, where physical distance and time are eliminated as constraints, communication and operation are instantaneous, opening radically new possibilities.

One of those with profound strategic significance is the inherent proclivity of AI, freed from material bonds, to grow its operating arenas into “global network platforms”—such as Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple, Microsoft, et al. Because these transcend geographic, linguistic, temporal and related traditional boundaries, questions arise: Whose laws can regulate them? How might any regulations be imposed, maintained and enforced? We have no answers yet.

Perhaps the most acute illustration of the danger here is with the field of geopolitics—national and international security, “the minimum objective of … organized society.” A beautifully lucid chapter concisely summarizes the history of these fields, and how they were successfully managed to deal with the most recent development of unprecedented weapons of mass destruction through arms control treaties between antagonists. But in the new world of cyberspace, “the previously sharp lines drawn by geography and language will continue to dissolve.”

Furthermore, the creation of global network platforms requires massive computing power only achievable by the wealthiest and most advanced governments and corporations, but their proliferation and operation are possible for individuals with handheld devices using software stored in thumb drives. This makes it currently impossible to monitor, much less regulate, power relationships and strategies. Nation-states may become obsolete. National security is in chaos.

The book goes on to explore how AI will influence human nature and values. Westerners have traditionally believed that humans are uniquely endowed with superior intelligence, rationality and creative self-development in education and culture; AI challenges all that with its own alternative and in some ways demonstrably superior intelligence. Thus, “the role of human reason will change.”

That looks especially at us higher educators. AI is producing paradigm shifts not only in our various separate disciplines but in the practice of research and science itself, in which models are derived not from theories but from previous practical results. Scholars and scientists can be told the most likely outcomes of their research at the conception stage, before it has practically begun. “This portends a shift in human experience more significant than any that has occurred for nearly six centuries …,” that is, since Gutenberg and the Scientific Revolution.

Moreover, a crucial difference today is the rapidity of transition to an “age of AI.” Whereas it took three centuries to modernize Europe from the Renaissance to the Enlightenment, today’s radically transformative period began in the late 20th Century and has spread globally in just decades, owing to the vastly greater power of our IT revolution. Now whole subfields can be transformed in months—as in the cases of cryptocurrencies, blockchains, the cloud and NFTs (non-fungible tokens). With robotics and the “metaverse” of virtual reality now capable of affecting so many aspects of life beginning with childhood, the relation of humans to machines is being transformed.

The final chapter addresses AI and the future. “If humanity is to shape the future, it needs to agree on common principles that guide each choice.” There is a critical need for “explaining to non-technologists what AI is doing, as well as what it ‘knows’ and how.” That is why this book was written. The chapter closes with a proposal for a national commission to ensure our competitiveness in the future of the field, which is by no means guaranteed.

Evaluation

The Age of AI makes a persuasive case that AI is a transformative break from the past and sufficiently powerful to be carrying the world into a new “epoch” in history, comparable to that which produced modern Western secular culture. It advances the age-of-paradigm-shifts-analysis by specifying that the driver is not just the IT revolution in general, but its particular expression in machine learning, or artificial intelligence. I have called our current period the “Transformation” to contrast it with the comparable but retrospective “Renaissance” (rebirth of Classical civilization) and “Reformation” (reviving Christianity’s original purity and power). Now we are looking not to the past but to a dramatically new and indefinite future.

The book is also right to focus on our current lack of controls over this transformation as posing an urgent priority for concerted public attention. The authors are prudent to describe our current transformation by reference to its means, its driving technology, rather than to its ends or any results it will produce, since those are unforeseeable. My calling it a “Transformation” does the same, stopping short of specifying our next, post-modern, period of history.

That said, the book would have been strengthened by giving due credit to the numerous initiatives already attempting to define guiding principles as a necessary prerequisite to asserting human control. Though it says we “have yet to define its organizing principles, moral concepts, or aspirations and limitations,” it is nonetheless true that the extreme speed and global reach of today’s transformations have already awakened leading entrepreneurs, scholars and scientists to its dangers.

A 2020 Report from Harvard and MIT provides a comparison of 35 such projects. One of the most interesting is “The One-Hundred-Year Study on Artificial Intelligence (AI100),” an endowed international multidisciplinary and multisector project launched in 2014 to publish reports every five years on AI’s influences on people, their communities and societies; two lengthy and detailed reports have already been issued, in 2016 and 2021. Our own government’s Department of Defense in 2019 published a discussion of guidelines for national security, and the Office of Technology and Science Policy is gathering information to create an “AI Bill of Rights.”

But while various public and private entities pledge their adherence to these principles in their own operations, voluntary enforcement is a weakness, so the assertion of the book that AI is running out of control is probably justified.

Principles and values must qualify and inform the algorithms shaping what kind of world we want ourselves and our descendants to live in. There is no consensus yet on those, and it is not likely that there will be soon given the deep divisions in cultures of public and private AI development, so intense negotiation is urgently needed for implementation, which will be far more difficult than conception.

This is where the role of academics becomes clear. We need to beware that when all fields are in paradigm shifts simultaneously, adaptation and improvisation become top priorities. Formulating future directions must be fundamental and comprehensive, holistic with inclusive specialization, the opposite of the multiversity’s characteristically fragmented exclusive specialization to which we have been accustomed.

Traditional academic disciplines are now fast becoming obsolete as our major problems—climate control, bigotries, disparities of wealth, pandemics, political polarization—are not structured along academic disciplinary lines. Conditions must be created that will be conducive to integrated paradigms. Education (that is, self-development of who we shall be) and training (that is, knowledge and skills development for what we shall be) must be mutual and complementary, not separated as is now often the case. Only if the matrix of future AI is humanistic will we be secure.

In that same inclusive spirit, perhaps another book is needed to explore the relations between the positive and negative directions in all this. Our need to harness artificial intelligence for constructive purposes presents an unprecedented opportunity to make our own great leap forward. If each of our fields is inevitably going to be transformed, a priority for each of us is to climb aboard—to pitch in by helping to conceive what artificial intelligence might ideally accomplish. What might be its most likely results when our fields are “shaken to their roots” by machines that have with lightning speed taught themselves how to play our games, building not on our conventions but on innovations they have invented for themselves?

I’d very much like to know, for example, what will be learned in “synthetic biology” and from a new, comprehensive cosmology describing the world as a coherent whole, ordered by natural laws. We haven’t been able to make these discoveries yet on our own, but AI will certainly help. As these authors say, “Technology, strategy, and philosophy need to be brought into some alignment” requiring a partnership between humans and AI. That can only be achieved if academics rise above their usual restraints to play a crucial role.

George McCully is a historian, former professor and faculty dean at higher education institutions in the Northeast, professional philanthropist and founder and CEO of the Catalogue for Philanthropy.

The Infinite Corridor is the primary passageway through the campus, in Cambridge, of MIT, a world center of artificial intelligence research and development.

Dana Farber and MIT joining in new cancer initiative

Part of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

“Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, in Boston, and Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), in Cambridge, have partnered along with three other organizations — Johns Hopkins University, in Baltimore, Memorial Sloan Kettering, in New York City, and MD Anderson, in Houston — in a pledge to treat the most challenging forms of cancer. Break Through Cancer, a new foundation backed by a $250 million donation from Mr. and Mrs. William H. Goodwin Jr. and the estate of the late William Hunter Goodwin III, who passed away in 2020 from cancer, will fund and support collaboration among the nation’s top cancer institutions.

“President Biden has expressed his support for the foundation, stating, ‘I’m delighted to see five of the nation’s leading cancer centers are joining forces today to build on the work of the Cancer Moonshot I was able to do during the Obama-Biden administration to help break through silos and barriers in cancer research.’ Break Through Cancer also focuses heavily on particularly challenging cancers, including pancreatic cancer, ovarian cancer, acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) and glioblastoma. Cancer experts and teams will receive substantial funding to develop innovative treatments, clinical trials, and cures.

“‘We realize there are no guarantees, yet we believe this effort to fight cancer, particularly with collaborative research, has a realistic probability of success,’ said Bill Goodwin. ‘We want to help people have better lives. And we sincerely hope that by being public with our support, we will inspire others to support this incredible effort.”’

Barely surviving the MIT miasma

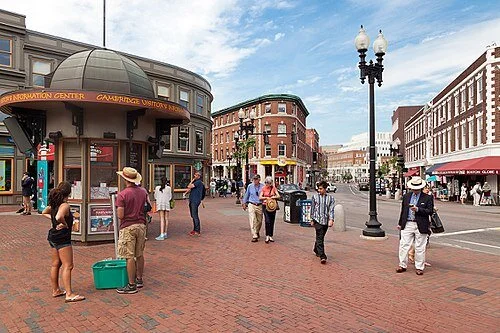

Harvard Square offices of "Dewey, Cheetham and Howe", headquarters of Car Talk

— Photo by Patricia Drury

“Boy, I hated MIT. I worked my butt off for four long years. The only thing that saved my sanity was the 5:15 Club, named, I guess, for the guys who didn’t live on campus and took the 5:15 train back home. Yeah, right, 5:15, my tush! I never got home before midnight!

— Tom Magliozzi (1937-2014), co-host, with his brother and fellow mechanic Ray (born 1949), of the long-running (1987-2012) NPR series Car Talk. Some NPR stations continue to broadcast reruns of some episodes. The brothers grew up in East Cambridge, very close to MIT, from which they both graduated.

Tom Magliozzi

John O. Harney: New England and other experts address racial and economic reckoning'

Logo of the Color of Change reform group

BOSTON

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

Even in this time when people presume to be having a “racial reckoning,” signs of enduring racial inequity pop up everywhere. From nagging disparities in health—Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC) die at higher rates than other groups from COVID-19 and are underrepresented in medical research (except in vile experiments such as in the Tuskegee study) … to the steep declines in Black and Latino students submitting the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) … to Black food-service workers experiencing disproportionate short-tipping for enforcing social-distancing rules … inequality reigns. These persistent forces should be a big deal for New England’s Historically White Colleges and Universities, which are rarely called out as HWCUs.

Some help is on the way. Beside targeting $128.6 billion for the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund, $39.6 billion to the Higher Education Emergency Relief Fund, $39 billion for child care and $1 billion for Head Start, the new $1.9 trillion coronavirus relief plan does other less visible things to begin to address structural racism. For example, the package provides Black farmers with debt relief and help acquiring land. Black farmers lost more than 12 million acres of farmland over the past century, attributed to systemic racism and inequitable access to markets.

I’ve been trying to monitor the racial-equity conversation mostly via Zoom since the pandemic began. This mention of aid to Black farmers reminded me of something I heard Chuck Collins say at a webinar convened last month by MIT’s Sloan School of Management via Zoom titled “The Inclusive Innovation Economy: Amplifying Our Voices Through Public Policy’’.

Collins is the director of inequality and the common good at the Institute for Policy Studies and a white man. He told of his uncle getting a 1 percent fixed-rate mortgage in 1949 to buy an Ohio farm—a public investment that led his cousins to get on “America’s wealth-building train.” Black and Brown people did not get the same benefits. Collins suggested that systems such as CARES relief should be examined with a racial-equity lens, as should policies such as raising the minimum wage or forgiving student loans. Unquestionably, Black students struggle more than whites with student debt. But with Capitol Hill debating the right amount of debt to forgive, Collins suggested we need to test how well these changes would affect racial inequity.

Dynastic wealth

Noting that we’re living through an updraft of “dynastic wealth,” Collins asked why the U.S. taxes work income higher than income from investments. He pointed out that “50 families in the U.S. that are now in their third generation of billionaires coming online and that represents a sort of Democracy-distorting and market-distorting concentration of wealth and power.”

That distortion could be partly cushioned with a “dignity floor,” said Collins. “It’s not a coincidence that a society like Denmark has much higher rates of entrepreneurship than the U.S. per capita because they have a social-safety net and because they have social investments that create a decency floor through which people cannot all. So if you want to start a business, you know you can take that leap and not end up living in your car.”

We need to disrupt the narrative of “everyone is where they deserve to be,” said Collins. So many entrepreneurs tell their story from the standpoint of I did this. We need to talk about the web of supports and multigenerational advantages behind their ability to take the step they took.

Color-coded

An audience member asked if a bridge could be built to connect the rich and poor. To this, one of the conversation moderators, Sloan School lecturer and former chief experience and culture officer at Berkshire Bank Malia Lazu, quipped that in the U.S., there’s another dimension: The sides of the bridge are “color-coded.”

Lazu and co-moderator Fiona Murray, associate dean for innovation and inclusion at Sloan, agreed that ironically this is how the policies were designed to work. That’s why we need to change how the systems are wired.

It’s not that Black people are less likely to get loans from banks, but that banks are less likely to give loans to Black people, explained Color of Change President Rashad Robinson. Shifting the subject that way, he said, has led to remedies like financial literacy programs for Black people, rather than changes in the policies of big banks.

Color of Change was formed in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, which, like COVID-19, disproportionately hurt Black and Brown people. Narrative is not static, Robinson said, reminding the audience of what people might have unabashedly said in the workplace about LGBT people just 15 years ago.

Moreover, budgets are “moral documents,” Robinson pointed out. So if you say you’re going to prosecute more corruption crimes than street crime, that has to be reflected in budgets. People of color are not vulnerable, they’ve been targeted, added Robinson, who is working on a report that will look at not only Black pain, but also Black joy and how BIPOC are portrayed in stories on TV.

An audience questioner asked which policies actually embed structural racism. Lazu pointed to the U.S. Constitution’s original clause declaring that any person who was not free would be counted as three-fifths of a free individual. For a more modern example, Robinson noted minimum-wage laws that exclude certain kinds of work, originally farm workers and domestic workers, now work usually done by people of color and women. Structural racism is rooted in how our economy is designed, said Robinson. “An equity focus means we’re not just trying to undo harm but we’re trying to create systems and structures that actually move us forward.”

Afraid to bring children into the world

Also last month, the Boston Social Venture Partners convened a Zoom webinar with affiliates in San Antonio and Denver to discuss how nonprofit leaders have struggled to implement strategies that funders require for diversity, equity and inclusion.

The conversation was moderated by Michael Smith, executive director of the Obama Foundation’s My Brother’s Keeper Alliance, based in Washington, D.C. The alliance was created in 2014 in the aftermath of the killing of Trayvon Martin and aimed at addressing opportunity gaps. It works today against the backdrop of the COVID pandemic and resulting school closures, an economic downturn and police violence in communities of color.

Another Obama fellow, Charles Daniels, the executive director of Boston-based Father’s Uplift, explained: “We have a shortage of clinicians of color in this country—sound, qualified therapists who are able to provide that necessary guidance,” he said. “One of the main requests of single mothers bringing their children to us or fathers entering our agency is that they want a clinician of color, someone who looks like them,” he said. “There are conversations they don’t know necessarily how to have with their loved ones about racism, about oppression, about maintaining their dignity and self-respect.”

Daniels noted that constituents are grappling with what to tell sons about getting pulled over by the police and daughters about what their school may say about hairstyles. “These are conversations that people of color dread this day and age. They wake up trying to parent their inner child and also parent the child who they brought into this world.” He notes that some constituents are actually afraid of having children for these reasons.

A young Black man told Daniels that if he had a choice to be white, he would take it: “I wouldn’t have to worry about my life every time I go to school,” the child suggested, or “an administrator being on my back in school because she’s assuming I’m not doing my work because I don’t care as opposed to me not being able to feed my stomach because I’m hungry.” Daniels said these are real-life situations that young men and single mothers struggle with on a daily basis.

When the federal government recently sent relief stipends, many men of color were left out for not paying child support as if they just didn’t want to pay, when the real reason was they couldn’t afford it.

Growing up as a person of color, you’re taught that you have to be near perfect. You can’t get away with things other populations can, said Daniels. He added: “If someone of color who you’re vetting sends an email with an error, it doesn’t mean they’re incompetent; it probably means they’re doing more than one thing or wearing two hats.” He said he likes funders who offer technical support, as well as authentic conversation, and who don’t avoid the word “racism.”

Giant triplets

Meanwhile, the Quincy Institute, led by retired U.S. Army colonel and noted critic of the Iraq War-turned Boston University professor Andrew Bacevich, held a virtual “Emergency Summit” of public intellectuals to reflect on America Besieged by Racism, Materialism and Militarism—the “giant triplets” identified by Martin Luther King, Jr. in his 1967 speech “Beyond Vietnam.”

Against the backdrop of the Jan. 6 Capitol insurrection, Bacevich began by asking the panelists how those triplets continue to threaten democracy.

One panelist, New York Times contributing writer Peter Beinart, noted that one of the triplets, materialism, while an enormous cultural problem, might not rank as one of the three main ones today because, unlike in the 1960s when people assumed that American living standards would be going up, many today suffer from a lack of materialism and hold very little hope that their situations will improve.

Militarism and racism, however, do persist. As a foreign-policy term, however, “militarist” has been replaced by euphemisms such as “muscular” or “tough-minded.” But militarism is plain to see in the degree to which domestic policing has been affected by military equipment, and veterans return home without decent healthcare. (As an aside, the military has been lauded for well-run coronavirus vaccine sites while the civilian counterparts are often cast as failures. Asked why this is on a recent television news show, Alex Pareene, a staff writer for The New Republic, offered a simple explanation: The U.S. has never disinvested in the military.)

One panelist, the Rev. Liz Theoharis, who is co-chair with Rev. William Barber, of the Poor People’s Campaign, said she would add to King’s triplets, two more demons: ecological devastation and emboldened religious nationalism evidenced on Jan. 6.

Regarding militarism, Theoharis noted that while there’s no military draft per se, there is a “poverty draft” because for many young people, it’s the only way to put food on their table and get an education. Yet, they come home to a lack of opportunity. The majority of single male adults that are homeless in our society are veterans. The military system is “not about the ideals of a democracy and opportunity and possibility and freedom for all, it’s sending poor people, Black people and Latino people to go and fight and kill poor people in other parts of the world,” she said, noting that the U.S. has military bases in more than 800 places. The coronavirus threat has spread in the fissures that we faced before in terms of racism and inequality, which were already claiming lives before the pandemic.

Neta C. Crawford, a professor and chair of political science at Boston University, said democracy is the antidote to militarism, extreme materialism and racism. Members of Congress are tightly connected to military bases and defense contractors in their districts based on the belief that the military-industrial complex creates good jobs. Crawford said we need break this misconception with solid analysis that shows military spending actually produces fewer jobs and what we could be doing instead.

Daniel McCarthy, editor of Modern Age: A Conservative Review and editor-at-large of The American Conservative, noted the irony that U.S. military adventures abroad are framed as antiracist. When he opposed the Iraq War, he was accused of being against Arab democracy and therefore racist. He lamented that we need to find something for the part of industrial America that has been declining, not necessarily related to militarism but to make things that people want to buy.

Justice and belonging in New England

This webinar surfing spree came as NEBHE renewed its focus on diversity, equity and inclusion. The terms “justice” and “belonging” are sometimes also added to the collection of values that used to be disparaged as so much p.c. Moreover, “diversity” is not enough on its own because, as one New England college president recently told his colleagues, people can feel welcomed but also disadvantaged. NEBHE has also looked at the concept of “reparative” justice as a way to recognize that fighting racial oppression should not be responsive to specific past wrongs, but rather, driven by the understanding that the past, present and future exist together.

To be sure, New England will thrive only if its education systems promote inclusion and excellence for learners of all backgrounds, cultures, age groups, lifestyles and learning styles in an environment that promotes justice and equity in a diverse, multicultural world.

John O. Harney is executive editor of The New England Journal of Higher Education.

A better networking app than Zoom?

“The Conversation” (circa 1935), by Arnold Lakhovsky

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

Northeastern University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology have developed an app to allow for causal networking. Minglr, a video conferencing app, seeks to replicate the experience of conference attendees bouncing ideas off each other in the real world.

Thomas Malone, founding director of the MIT Center for Collective Intelligence, worked with MIT Sloan doctoral student Jaeyoon Song and Chris Riedl, an associate professor at Northeastern’s D’Amore McKim School of Business, to create the app. Currently, the Minglr is a fairly simple program, with users inputting their primary interests and selecting individuals to talk to. If the selection is mutual, a chat window will be opened. The team hopes that Minglr will allow conference goers to participate in the informal flow of ideas characteristic of conferences and innovation.

“It was so much better than being in just one giant Zoom meeting,” said Malone, who tried out the system at MIT’s Collective Intelligence 2020 virtual conference in June. “I had all the kinds of conversations you’d have in the lobby of a conference.” A survey of attendees who tested Minglr found that 86 percent liked the system and wanted it made available for future conferences, he said.

The New England Council congratulates MIT and Northeastern on their innovative work to tackle one of the many unique challenges created by the COVID-19 pandemic. Read more from the Boston Globe.

Foreign students are a boon for New England

Harvard Square

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

It was good news that the Trump administration has rescinded an order that would have stripped visas from foreign students whose courses are moved exclusively online because of the pandemic. Various institutions, led by Harvard and MIT, had sued to block the order, which seemed to many to be obviously illegal. There are hundreds of thousands of such students in America, with tens of thousands in New England.

Trump pushed the visa ban, which would have caused administrative and financial chaos, to try to force colleges and universities to reopen all in-person courses despite the raging pandemic, presumably because he thought that it would be a signal that things were returning to normal, thus boosting the pre-election economy? And he doesn’t like immigrants anyway.

Foreign students are particularly important in New England – economically and otherwise – because of the region’s world-famed colleges and universities. They bring a lot of energy, ambition and a hefty work ethic and help connect us with, and teach us about, the rest of the world. That makes our region more competitive. And some of the best stay and become Americans. Look at all the foreign-born health-care professionals dealing with COVID-19 and the large number of foreigners who have stayed in New England to create successful, high-paying companies based here, most notably in technology.

.

A robot that disinfects surfaces

The Stata Center houses CSAIL, at MIT. No, the building isn’t collapsing; it’s supposed to look like this…

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

“The Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL) at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) collaborated with Ava Robotics and the Greater Boston Food Bank to design a new system to disinfect surfaces and neutralize airborne contaminants. The system uses a UV-C light fixture to kill the virus, however, the light is not safe for human interaction. Fortunately, the new robot is completely autonomous and can be used for the disinfection of restaurants, factories and supermarkets. Given the stress that food banks are under to reduce food insecurity, the robot could be a helpful tool to keep essential workers safe.’’

To see picture and read more, please hit this link.

Llewellyn King: The case for continuous scientific research

Oxford’s Jenner Institute laboratories seen from the atrium

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

There is something fabulously exciting about watching science riding to the rescue. The gloom about the coronavirus pandemic began to lift dramatically in the past several days as good news about vaccines came out.

Out front Oxford University, with a well-established history in vaccines, announced that it had started trials on people and that it might have a vaccine by September. It has a manufacturing partnership with AstraZeneca, a giant European pharmaceutical company, and it is hoped that a million doses can be produced by September, even as there is not absolute certainty that it will work. Sarah Gilbert, professor of vaccinology at Oxford’s Jenner Institute, says she is “80 percent” certain that it will.

Incidentally, some of tests on rhesus macaque monkeys were done at the National Institutes of Health’s Rocky Mountain Laboratories, in Hamilton, Mont.

Labs in all major countries are in close pursuit of Oxford. What does seem certain is that the time when a viable vaccine can be brought to market is shrinking. The next challenge will be to manufacture proven vaccines in the hundreds of millions of doses needed.

To me the big thing is not who finds a vaccine, but rather how science answers the call to arms when the challenge is there – and financial support is provided. Much critical research in many of the coronavirus vaccine efforts has been provided not by governments, but by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

There is reason to wonder why Gates has been out in front of many governments, including the United States. This points to government failure to adequately support research and to prepare non-military defenses. Not every threat a modern nation faces comes from national armed forces.

Across the spectrum of research, private money is raised to do the work which should be in the government’s purview. Money for science is a struggle: There are competing philosophies, political and scientific, about research. To begin with, all research is messy. The scientific method, as Michael Short of MIT reminded me recently, is based on try, fail, try again; test, prove, then proceed.

Conservatives have tended to be skeptical about a lot of science, pooh-poohing the study of obscure microbes and what they see as dubious investigation. They have consistently demanded quantifiable results from the government’s scientific establishment, looking for practical applications and unhappy about research for its own sake. They have forgotten the real driver of all science: to know.

Liberals have favored, as you would expect, the social sciences over the hard ones. They are more prepared to treat social studies as science than high-energy physics.

What is lacking is something which we used to have in Congress: the Office of Technology Assessment which was the scientific equivalent of the Congressional Budget Office. As with the often-quoted CBO, the OTA was a tool for members of Congress; a means for them to get complex scientific issues right and help them to understand the budgeting for those.

The OTA was created in 1972 and looked to be a firm part of the support system of Congress. But the Newt Gingrich-led House axed it in 1995. There have been several attempts to bring the OTA back in the House; last year a bill was introduced that would have reestablished it at a modest $6 million, but no action was taken.

The OTA provided a valuable service in saving members of Congress from themselves; advising them when they come back from their constituencies believing hearsay as scientific fact -- the same thing that has bedeviled President Trump in his briefings on the COVID-19 crisis.

I was well acquainted with the OTA and I always thought its greatest value was not in its formal advice, but rather in its informal help to members -- who often confuse what they are told by sources as disparate as their children and lobbyists -- from saying something about science that did not hold up.

As it is, we are all standing where we can see the scientific cavalry saddle up and ride out. This is heart-pumping, reassuring and confirms that science should not be neglected for budget or other reasons. To have a viable scientific infrastructure is to be defended from non-military attack, ranging from cybersecurity to a virus. Scientists agree on this: There will be more.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he is based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

'All that is good and noble'

The Rogers Building, in Boston’s Back Bay district, was opened in 1865 as MIT’s first building erected specifically for the institution. MIT, founded in 1861 and often called “Boston Tech’’ in its earlier years, was moved to Cambridge in 1916.

“I never fully realized how much a New England birth in itself was worth, but I am happy that that was my lot. I have felt it so keenly these last few days. Dear old New England, with all her sternness and uncompromising opinions; the home of all that is good and noble.”

― Matthew Pearl, in his novel The Technologists, set in the early years of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

N.E. responds to pandemic: Spot the robot helps out; Vermont Teddy Bear switches to PPE's

Spot helping out at Brigham and Women’s Hospital

From our friends at The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

As our region and our nation continue to grapple with the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) pandemic, The New England Council is using our blog as a platform to highlight some of the incredible work our members have undertaken to respond to the outbreak. Each day, we’ll post a round-up of updates on some of the initiatives underway among Council members throughout the region. We are also sharing these updates via our social media, and encourage our members to share with us any information on their efforts so that we can be sure to include them in these daily round-ups.

You can find all the Council’s information and resources related to the crisis in the special COVID-19 section of our website. This includes our COVID-19 Virtual Events Calendar, which provides information on upcoming COVID-19 Congressional town halls and webinars presented by NEC members, as well as our newly-released Federal Agency COVID-19 Guidance for Businesses page.

Here is April 24 roundup:

Medical Response

UMass Memorial Receives $120,000 Grant for Telemedicine – UMass Memorial Health Center has received a $120,000 grant to implement and expand telemedicine technology during the pandemic. The hospital aims to specifically prioritize spending on pediatric and emergency units as well as on remote primary response areas. The Worcester Business Journal has more.

MIT, Beth Israel Collaborate to 3-D Print Testing Materials – Faced with a shortage of essential testing materials such as swabs, researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) entered into a partnership to 3-D print the necessary materials. Four prototypes have since been clinically validated, and the hospital expects to soon be able to produce more than a million swabs per day Boston.com has more.

Economic/Business Continuity Response

Brigham and Women’s Hospital Using Robot to Reduce Staff Exposure – To reduce infections of COVID-19 among staff, Brigham and Women’s Hospital has begun using a four-legged robot (named Spot) from Boston Dynamics to allow providers to remotely video conference with patients in triage tents. The technology allows for reduced exposure between patients and providers and streamlines the testing process. Read more from Boston.com.

Vermont Teddy Bear Factory Producing Equipment for Essential Businesses and Healthcare Providers – With production halted, the Vermont Teddy Bear Factory, in Shelburne, has pivoted operations to produce face masks and other personal protective equipment (PPE) for both healthcare providers and essential workers. In addition, the company will make the masks from recycled materials to remain sustainable. More from WCBS

Community Response

Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts Pledges $107,000 for Community Relief – Health insurance provider Blue Cross Blue Shield of Massachusetts (BCBS) has announced more than $107,000 to support nonprofits in the Commonwealth, including the United Way of Massachusetts Bay and Merrimack Valley, that provide relief and aid. The additional support comes after BCBS had previously announced over $1.1 million in other relief measures. Read more in the Lynn Journal.

UnitedHealth Group Donates $5 Million for Treatment Development – UnitedHealth Group has pledged $5 million to support a federally-sponsored program that aims to develop a plasma treatment for the virus,. The effort is led by the Mayo Clinic and utilizes the plasma from recovered COVID-19 patients as a potential treatment. Read the release here.

Webster Bank Commits $100,000 to Support Efforts – Webster Bank has donated $100,000 to United Way to support efforts to aid communities affected by the pandemic. The funds will be used to provide food, childcare, and other services to organizations strained by revenue losses. The Hartford Business Journal reports.

Stay tuned for more updates each day, and follow us on Twitter for more frequent updates on how Council members are contributing to the response to this global health crisis.

N.E. virus response: MIT leads smartphone tracking; Sanofi joins vaccine partnership; more

“Contact Tracing” ( encaustic monotype), by Nancy Whitcomb

From The New England Council (newenglandcouncil.com)

BOSTON

As our region and our nation continue to grapple with the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) pandemic, The New England Council is using our blog as a platform to highlight some of the incredible work our members have undertaken to respond to the outbreak. Each day, we’ll post a round-up of updates on some of the initiatives underway among Council members throughout the region. We are also sharing these updates via our social media, and encourage our members to share with us any information on their efforts so that we can be sure to include them in these daily round-ups.

You can find all the Council’s information and resources related to the crisis in the special COVID-19 section of our Web site. This includes our COVID-19 Virtual Events Calendar, which provides information on upcoming COVID-19 Congressional town halls and webinars presented by NEC members, as well as our newly-released Federal Agency COVID-19 Guidance for Businesses page.

Here is the April 20 roundup:

Medical Response

MIT Leads Global Efforts for Smartphone Tracking – Around the world, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is supporting and leading efforts to track COVID-19 infections. Using Bluetooth signals emitted from smartphones to conduct “contact tracing” on those with access to phones could eliminate much of the work for state and local governments to identify infected individuals. Read more in The Boston Globe

Sanofi Enters Partnership to Speed Development of Vaccine Prototype – Sanofi has partnered with GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) to work together in developing a vaccine for the coronavirus. The two pharmaceutical companies will combine their existing supply chains and resources to expedite both clinical trials of their vaccine candidate and production should theirs prove effective. BioPharma Dive has more.

Boston University Medical School Students Graduate Early to Aid Local Hospitals – Students from Boston University’s medical school have graduated early to begin their residencies in the midst of the global pandemic. Those newly-minted doctors who choose to remain in Massachusetts will receive automatic 90-day provisional licenses to allow them to begin practicing immediately. Read more in The Boston Business Journal.

Economic/Business Continuity Response

MEMIC Releases Workforce Guidance Hub – The Maine Employers Mutual Insurance Company (MEMIC) has launched a resource center for employees to inform them of proper safety precautions and legal protections offered to them as they navigate working during the pandemic. Additionally, the site offers additional aid to policyholders, including the suspension of non-renewals and adjustments to payment plans. Read more.

UMass Memorial Launches Employee Monitoring Program – To ensure that the hospital can remain open safely, UMass Memorial Medical Center has initiated a new program requiring all staff to log if they are experiencing any symptoms of COVID-19 before starting a shift. The measures aim to protect patients and staff as they work to contain the spread of the virus. The Worcester Business Journal has more.

Verizon Continuing to Expand 5G Network – Despite suspending marketing launches, Verizon is still on-track to launch 5G internet service in 60 cities by the end of the year. The provider will be using state-of-the-art technology to expand and improve access across the country, with cities such as Providence and Chicago already seeing 5G being implemented. Read more from PC Magazine.

Community Response