Ukrainian modern art and national identity

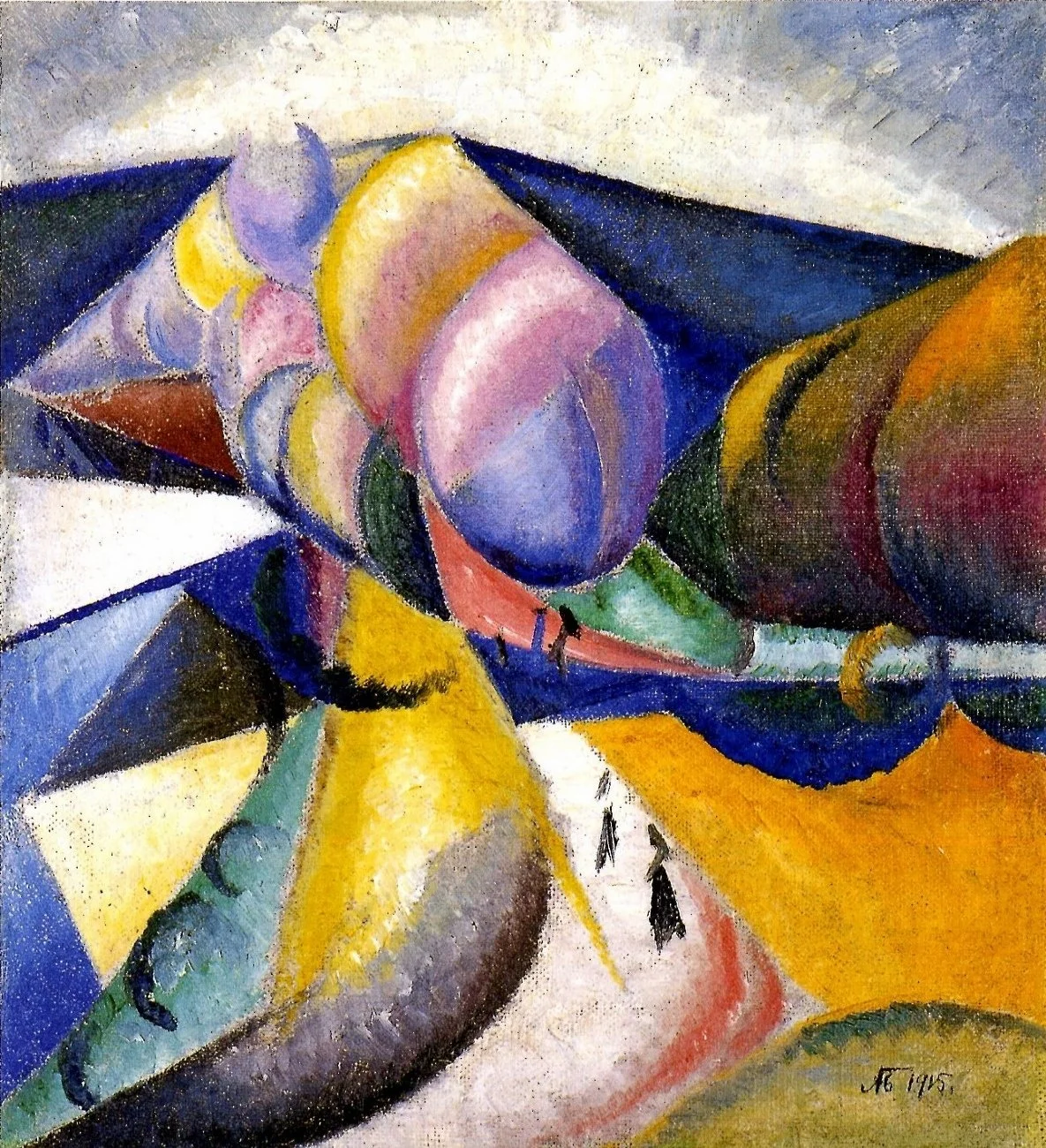

“The Caucuses (Geryusi)’’ (1915) (oil on canvas), by Oleksandr Bohomazov, in the show “The Juncture: Ukrainian Artists in Search of Modernity and Identity,’’ at the Mead Art Museum, at Amherst (Mass.) College, May 24-Oct. 13.

— Image courtesy of James Butterwick Gallery, London.

The museum says:

“This exhibition showcases the work of three leading modern artists from Ukraine who produced work during an astonishing period of the country’s cultural renaissance in the early 20th Century: Alexander Archipenko (1887–1964), Oleksandr Bohomazov (1880–1930), and Vasyl Yermilov (1894–1968). Modern and cosmopolitan by nature, their art also addresses the issues of national cultural identity at a time when their compatriots were trying to establish an independent Ukrainian state. The strikingly different fates of the three artists demonstrate the tectonic shifts and upheavals that their country underwent in the first half of the twentieth century. Their work—connected with Cubism, Futurism, Abstractionism, and Constructivism—reflects the stylistic diversity of the avant-garde landscape in Ukraine at that time. ‘‘

Interacting environments

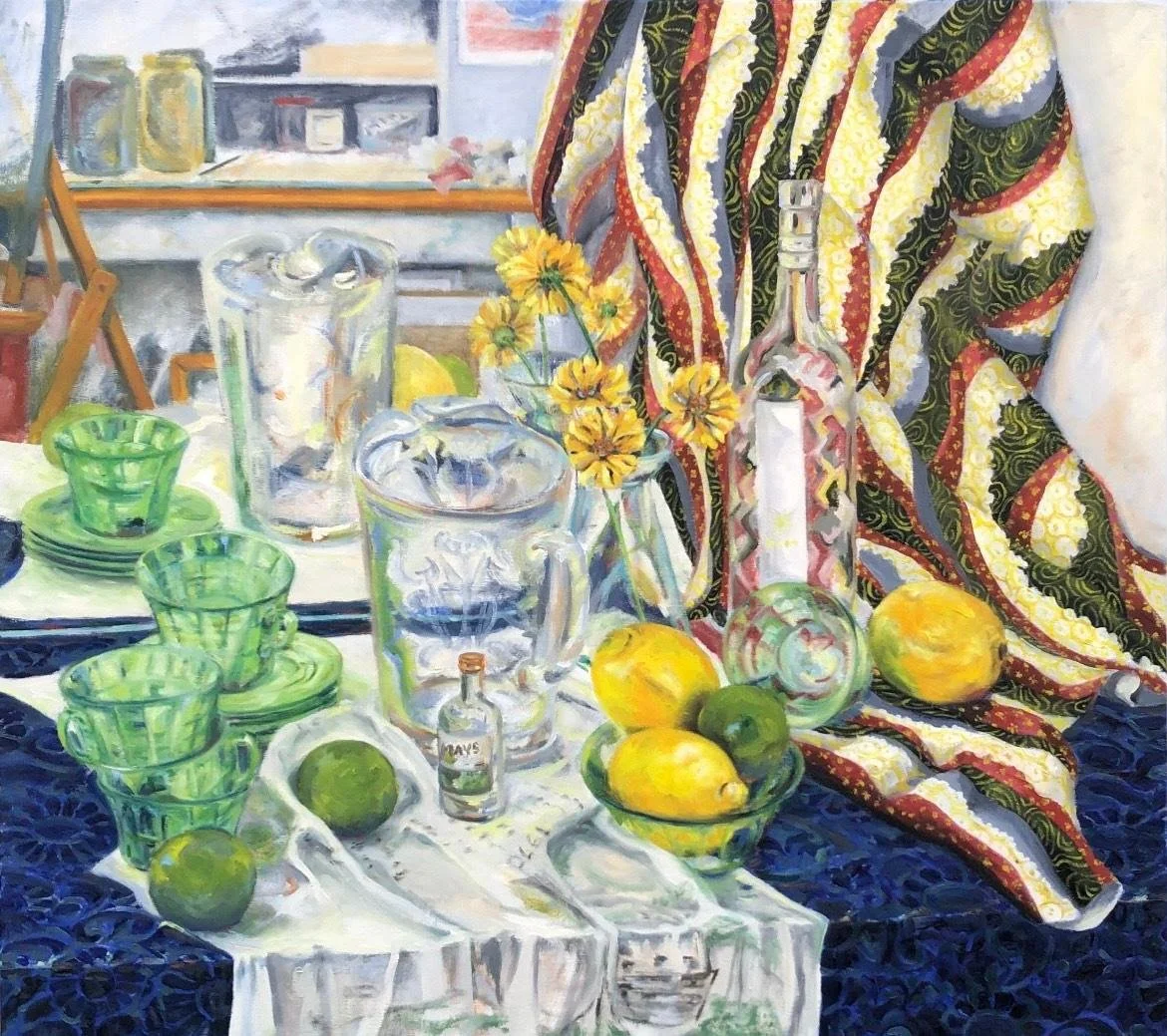

From “Stems — Paintings by Melinda Lane’’, at Colo Colo Gallery, New Bedford, Mass., through Dec 31.

‘

She says on her Web site:

“Influenced by New England's architecture, and decorative arts I create paintings of interior spaces filled with objects that interest me. I focus on the interaction of decorative materials and nature. The interplay of the natural world and the decorative environment reveals itself as I study the selected objects and the surfaces they occupy. Patterns and rhythms develop as I work to create the structure and space of an interior landscape.

”The process begins with the consideration of objects, surfaces, and vantage points. Common items mix with found objects and plant material as I use color, design, and materials to create an entry point for each painting. These spaces evolve through I study of the objects in situ and develop a geometric scaffold which creates a compositional framework. How do objects interact with each other? How do they sit in space and on the surface? Do color and pattern create movement and rhythm? What shapes and ideas do I discover as I spend time looking? How many layers do I see, and do these layers create an engaging image?

”Over time, sustained observation moves me beyond literal representation, and I create a singular space from a myriad of instances, both observed in the moment and remembered experiences. Rather than present an image, I work to create a space in which the viewer can dwell, explore, and discover their own thoughts and pleasures.’’

Scanning the ‘undertow’

“Each, Every, All, None’’ (mixed media), by Brockton, Mass.-based artist Virginia Mahoney in her show with Natalie Miebach, “Undercurrents,’’ at Fountain Street Gallery, Boston, through Oct. 29.

The gallery says:

“Virginia Mahoney scans the undertow of human interactions, examining the disparity between surface appearances and underlying consequences. With complex, intricate forms and materials, her figures probe autobiographical stories and question accepted narratives. As she uncovers possibilities in the scraps, shards, and leftovers of a longstanding studio practice, her voice emerges in the rhythm of stiches, provocations of language, and discovery of new forms.’’

Headlines posted in street-corner window of newspaper office (Brockton Enterprise), 60 Main Street, Brockton, in December 1940. Upstairs were the first main offices of the W.B. Mason company.

‘Oh what a town to get lost in’

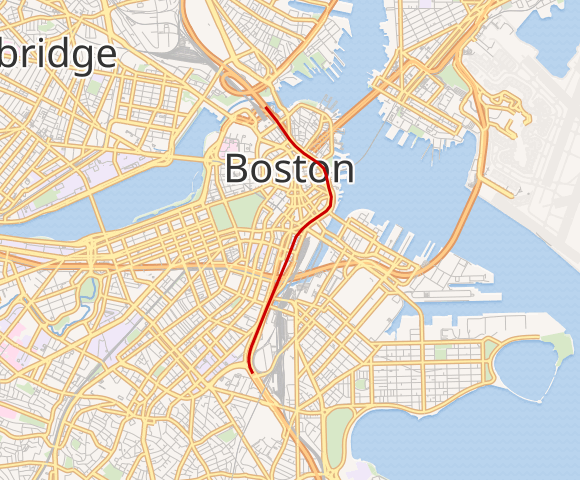

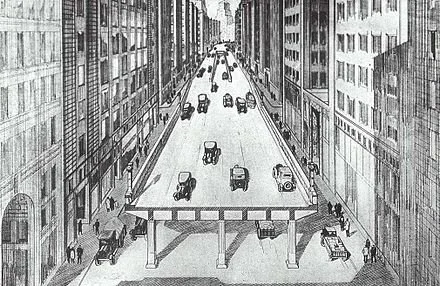

Central Artery is in red.

1920 plan for the Central Artery.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s May 22 “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

I drove up through Boston to Medford, Mass., on May 22 to have dinner with a niece, her husband and their son (8) and daughter (11). I did so with some trepidation because Boston and its inner suburbs have such tangles of streets and bad/confusing/nonexistent signage that GPS often can’t handle it in any coherent way and maps on paper tend to be outdated. And indeed, it was tough to find the restaurant on the Fellsway.

“Boston, Boston, Boston/Oh what a town to get lost in” as an old song goes. I lived in the city in 1970-71, and had jobs there in the ‘60s, and it doesn’t seem to be less confusing than it was back then, whatever the grandeur and promises of the Big Dig projects.

Greater Bostonians, like Rhode Islanders, are infamous for bad driving – not signaling, accelerating without warning on the right, swerving and so on. But the former are worse because they commit these sins at higher speeds.

Having dinner with children, especially bright, engaging ones like the ones mentioned above is fun, but it’s always good to bring games and reading materials for them. Few things are as boring to children as being trapped at a table for a long meal with adults while impatiently awaiting dessert.

At Fenway: Robert Whitcomb (left), the Sox’ Wally mascot and Boston publisher David Jacobs before the May 20 Mariners game.

However confusing Boston is, I tip my hat to the efficiency of the Boston Red Sox. Boston’s biggest weekly paper, The Boston Guardian, on whose little board I sit, was being honored, with other community organizations, in a pre-game event on the field at Fenway Park, on May 20, just before a game with the Seattle Mariners. (Boston won.) I’ve rarely seen such smooth coordination in moving people (including me) onto and off the field for the photo ops, etc.

It was comforting – sort of -- to see the police snipers on the roof of the stadium, ready for a terrorist attack or just another deranged young man with an assault rifle he just bought at Walmart. “Aren’t you happy they’re up there?’’ one of the photographers said.

I had to head back to Providence before the game ended and so had to leave the fancy lounge in the nose-bleed section above Fenway’s stands before Sox and Boston Globe principal owner John Henry showed up and played the guitar for our little group. He’s become my hero for supporting bookstores.

Boston can be beautiful, if exasperating! I fondly remember from the ‘60s running around the still somewhat Dickensian “Hub’’ on job errands, many of which I’d volunteer for to get out of stuffy offices, first in a shipping company on the waterfront and then at the gritty tabloid newspaper the Record American. I’d go to the tiny local stock exchange to pick up the day’s trading records or to the glorious State House to get something from a politician or a bureaucrat and nip into an ice-cream shop (or, as they were often spelled then, shoppe) for myself and into tobacco stores to buy cigarettes and cigars for my older co-workers. Occasionally I’d pick up a bag of peanuts to feed the rapacious pigeons on the Boston Common.

I did most of this walking, which is far and away the best way to get around the city.

‘Grief and love within the frame’

“Through the dahlias, backyard, Auburndale’’ (archival digital print), by Mary Lang, in her show “Farandnear,’’ at Kingston Gallery, Boston, June 1-26. She lives in Auburndale, part of Newton.

The gallery says:

“Mary Lang is known for her large scale, evocative color photographs, and for the groundless feeling of space held within the frame. These new images in ‘Farandnear’ hold space differently, encompassing both near and far in composition and focus. We often feel like we are looking past or through a screen or veil. There is a complexity in the details that both draw the viewer in and at the same time hold us back. Similarly for Lang, the climate crisis feels both far -- in that we can’t fully comprehend the most horrific events yet to come, so we push them away — and unbelievably near, in that mere observation of ice on the Charles River or plants in the garden tell us what is happening before our eyes.

“The exhibition is titled “Farandnear’’ after a Massachusetts Trustees of Reservations property in Shirley, an historic summer home aptly named because it was ‘far’ enough to require a two-day journey by horse to reach, but ‘near’ enough to be a vacation home. Lang’s camera records wild beaver swamps and ordinary urban patches of weeds, as well as images of her garden, in equal measure. The images are lush with growth; even in winter the earth offers an abundance. She says: ‘For me there is no distinction between the beauty of the untouched landscapes or the ones we often overlook because they are ubiquitous. It’s a matter of paying attention. They all hold both grief and love within the frame’’’

Old Shirley Town Hall

Shirley Shaker Village in 1884

The Turtle Lane Playhouse, in Auburndale

‘Pure, blank sheet’

Administration Building at McLean Hospital

— Photo by John Phelan

“A fresh fall of snow blanketed the asylum grounds — not a Christmas sprinkle, but a man-high January deluge, the sort that snuffs out schools and offices and churches, and leaves, for a day or more, a pure, blank sheet in place of memo pads, date books and calendars.’’

From autobiographical novel The Bell Jar, by Sylvia Plath (1932-1963). She was depressed most of her life and killed herself. The “asylum’’ she refers to is probably McLean Hospital, in Belmont, Mass.

17th Century marketing

“The First Thanksgiving at Plymouth”, by Jennie Augusta Brownscombe (1914), in Pilgrim Hall Museum, Plymouth, Mass.

“Loving Cousin,

“At our arrival {from England} at New Plymouth, in New England, we found all our friends and planters in good health, though they were left sick and weak, with very small means; the Indians round about us peaceable and friendly; the country very pleasant and temperate, yielding naturally, of itself, great store of fruits, as vines of divers sorts, in great abundance. There is likewise walnuts, chestnuts, small nuts and plums, with much variety of flowers, roots and herbs, no less pleasant than wholesome and profitable. No place hath more gooseberries and strawberries, nor better. Timber of all sorts you have in England doth cover the land, that affords beasts of divers sorts, and great flocks of turkeys, quails, pigeons and partridges; many great lakes abounding with fish, fowl, beavers, and otters. The sea affords us great plenty of all excellent sorts of sea-fish, as the rivers and isles doth variety of wild fowl of most useful sorts. Mines we find, to our thinking; but neither the goodness nor quality we know. Better grain cannot be than the Indian corn, if we will plant it upon as good ground as a man need desire. We are all freeholders; the rent-day doth not trouble us; and all those good blessings we have, of which and what we list in their seasons for taking. Our company are, for the most part, very religious, honest people; the word of God sincerely taught us ever Sabbath; so that I know not any thing a contented mind can here want. I desire your friendly care to send my wife and children to me, where I wish all the friends I have in England; and so I rest.’’

“Your loving kinsman,

William Hilton”

The autumn of 1621 is supposed to have been when “The First Thanksgiving’’ took place— a cooperative affair between the Calvinist Pilgrims who had landed at what they named Plymouth the year before and some Wampanoags, those who has survived the epidemics of disease brought by English sailors and traders in Maine after 1600. These epidemics had killed most of the Native Americans in eastern New England before the Pilgrims arrived.

Lindsay Koshgarian: The wasted opportunities since 9/11

Flight paths of the 9/11 murderers

Via OtherWords.org

NORTHAMPTON, Mass.

Twenty years have now passed since 9/11.

The 20 years since those terrible attacks have been marked by endless wars, harsh immigration crackdowns and expanded federal law enforcement powers that have cost us our privacy and targeted entire communities based on nothing more than race, religion, or ethnicity.

Those policies have also come at a tremendous monetary cost — and a dangerous neglect of domestic investment.

In a new report I co-authored with my colleagues at the National Priorities Project at the Institute for Policy Studies, we found that the federal government has spent $21 trillion on war and militarization both inside the U.S. and around the world over the past 20 years. That’s roughly the size of the entire U.S. economy.

Even while politicians have written blank checks for militarism year after year, they’ve said we can’t afford to address our most urgent issues. No wonder these past 20 years have been rough on U.S. families and communities.

After often strong growth from 1970 to 2000, household incomes have stagnated for 20 years as Americans struggled through two recessions in the years leading up to the pandemic. As pandemic eviction moratoriums end, millions are at risk of homelessness.

Our public-health systems have also been chronically underfunded, leaving the U.S. helpless to enact the testing, tracing, and quarantining that helped other countries limit the pandemic’s damage. Over 650,000 Americans have died from COVID-19 — the equivalent of a 9/11 every day for over seven months. The opioid epidemic claims another 50,000 lives a year.

Meanwhile, such extreme weather events as wildfires, hurricanes and floods have grown in frequency over the past 20 years. The U.S. hasn’t invested nearly enough in either renewable energy or climate resiliency to deal with the increasing effects climate change has on our communities.

In the face of all this suffering, it’s clear that $21 trillion in spending hasn’t made us any safer.

Instead, the human costs have been staggering. Around the world, the forever wars have cost 900,000 lives and left 38 million homeless — and as the disastrous withdrawal from Afghanistan has shown us, they were a massive failure.

Our militarized spending has helped deport 5 million people over the past 20 years, often taking parents from their children. The majority of those deported hadn’t committed any crime except for being here.

And it has paid for the government to listen in on our phone calls and target communities for harassment and surveillance without any evidence of crime or wrongdoing, eroding the civil liberties of all Americans.

Fortunately, there’s a silver lining: We’ve found that for just a fraction of what we’ve spent on militarization these last 20 years, we could start to make life much better.

For $4.5 trillion, we could build a renewable, upgraded energy grid for the whole country. For $2.3 trillion, we could create 5 million $15-an-hour jobs with benefits — for 10 years. For just $25 billion, we could vaccinate low-income countries against COVID-19, saving lives and stopping the march of new and more threatening virus variants.

We could do all that and more for less than half of what we’ve spent on wars and militarization in the last 20 years. With communities across the country in dire need of investment, the case for avoiding more pointless, deadly wars couldn’t be clearer.

The best time for those investments would have been during the past 20 years. The next best time is now.

Lindsay Koshgarian directs the National Priorities Project at the Institute for Policy Studies. She’s the lead author of the new report “State of Insecurity: The Cost of Militarization Since 9/11’’. She lives in Northampton.

On the Connecticut River in Northampton

A busy and early summer place

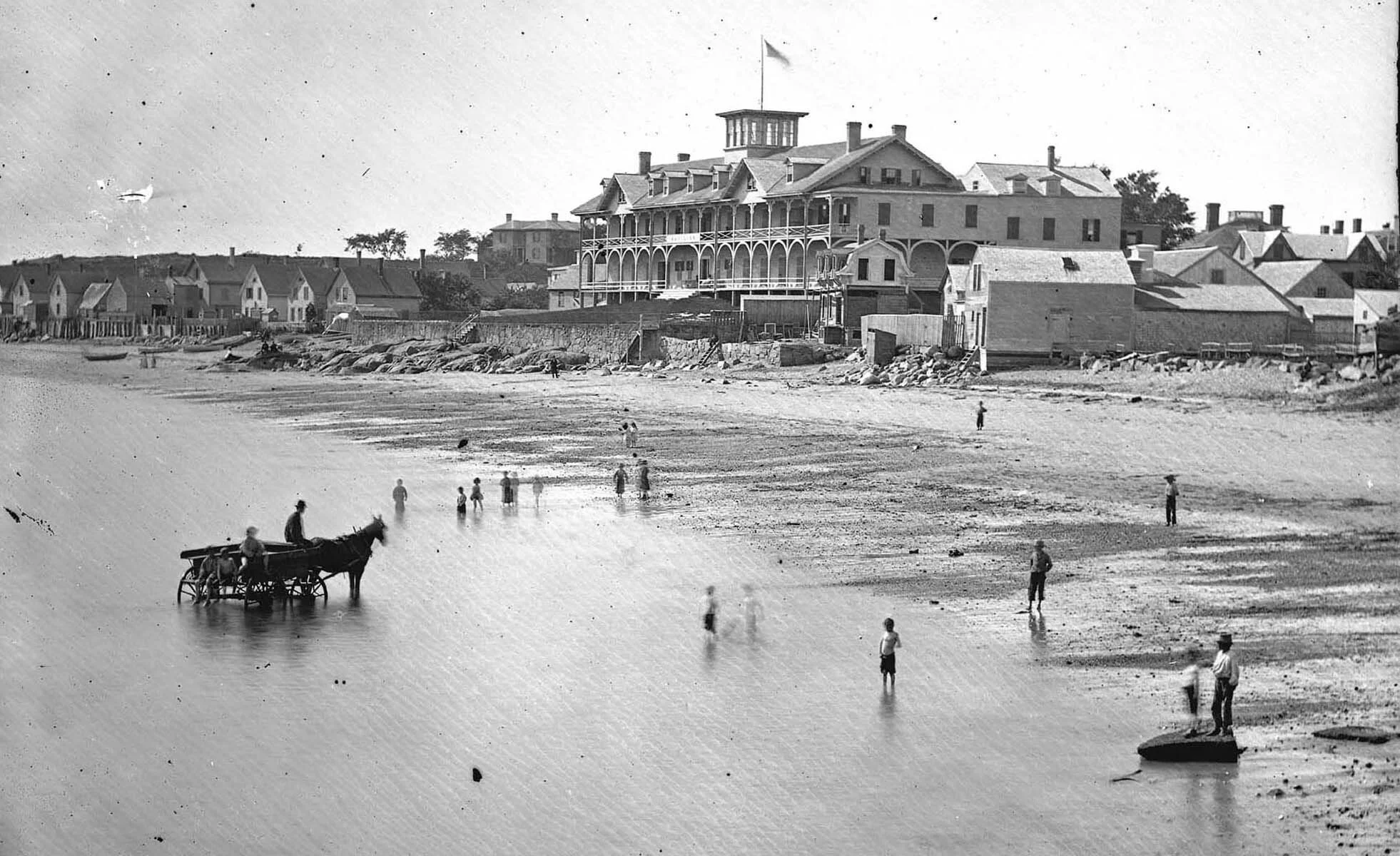

Architectural drawing of the Pavilion Hotel, in Gloucester, Mass., designed by S.C. Bugbee, for Sidney Mason, and built in 1849. The drawing is at the Cape Ann Museum, Gloucester. The long-gone hotel was the first big summer resort hotel on Cape Ann, serving the era’s growing bourgeoisie as New England’s economy boomed. Finished version below.

But just water vapor

“Forbidding & Sublime”” (oil painting), by Linda Pearlman Karlsberg, at Alpers Fine Art, Andover, Mass.

'The Old England of New England'

The Wayside, in Concord, Mass., home in turn to the Alcott family, novelist Nathaniel Hawthorne and writer and publisher “Margaret Sidney’’ (a nom de plume )— real name was Harriett Lothrop.

—- Photo by Dadero

“I perceive that I am neither a planter of the backwoods, pioneer, nor settler there, but an inhabitant of the Mind, and given to friendship and ideas. The ancient society, the Old England of New England, Massachusetts for me.”

— Amos Bronson Alcott (1799-1888), an American teacher, writer, philosopher and reformer, father of writer Louisa May Alcott (Little Women, etc.) and member of the famous literary community of Concord, Mass.

That's entertainment

“Lead Singer’’ (painting, cropped), by Bill Evaul, in his show “Song and Dance: Expressions from Life,’’ at the Cape Cod Museum of Art, Dennis, through Nov. 30.

The museum says that his show highlights his paintings, prints and drawings from across 40 years of Mr. Evaul's prolific artistic career, in which he has often sketched from life, “drawing inspiration from the performance of musicians and dancers”.

Scargo Tower, in Dennis, sits atop Scargo Hill, one of the tallest (160 feet) and best-known hills on Cape Cod. There have been three Scargo towers on this spot. The first was built in 1874 by the Tobey family, whose roots in the area go back to the 17th Century. A gale destroyed that wooden structure in 1876. Fire destroyed the second tower, known as "Tobey Tower" and also made of wood, in 1900. The present tower was wisely built of cobblestone in 1901 as a memorial to the Tobey family.

David Warsh: The Streaming Age

“The Future is Streaming,” trumpeted the 16-page special section of the Dec. 1 New York Times. I knew in my bones they were right. “Are you ready?” they asked.

Most definitely, I learned, I was not.

Much of what I know about developments in the stories I follow, I learn from the four newspapers I read daily: the NYT, The Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times, all on paper, and, online, The Washington Post. I especially gain from paying attention to the differential treatments in their coverage of particular stories, internal (news columns vs. editorial pages) and external (one paper vs. the others). I read parts of a lot of books, and all of some of them. I watch almost no television, hardly use Netflix and seldom see a movie at the corner theater, an old vaudeville palace now flanked by four smaller screening rooms on one side.

My budget, both time and money, began to change last week as a result of reading the Times section. In itself, that was no easy matter, since half of it was a 48-inch-wide pull-out (a double-double truck of facing pages, in newspaper parlance) containing a stylized map of representative content from the 271 entities in the new streaming universe, with articles printed on th other side. The idea of the map was offer guidance on various approaches to viewing, depending on one’s tastes and pocketbook: the Frugalist, the Harried Parent, the Fan(atic), the Connoisseur, the Escapist, the Omnivore.

Brooks Barnes, a Times reporter who covers Hollywood, wrote the lead piece. Four times in the last hundred years, more or less every 30 years, every three decades, enough to define several generations, he wrote, Hollywood has experienced a “seismic shift.” These seem to have been a matter of technological change.

In the 1920s, Talkies (and radio) supplanted vaudeville. In the 1950s, broadcast television took center stage. In the 1980s, the cable boom took over, led by music videos. Now the long-promised streaming revolution is at hand – entertainment over the Internet. Netflix began streaming movies and TV movies in 2007. Recently it financed Martin Scorsese’s latest gangster movie, The Irishman, starring Robert De Niro and Al Pacino, betting that far more people would rather watch a three-hour epic at home, rather than in theaters. The Irishman may be the first very expensive movie to depend primarily on streaming to recover its very high costs. Now, Barnes wrote, the three biggest old-line media companies – Disney, NBCUniversal, and WarnerMedia – were about to join in.

In another article, The Great Streaming Space-Time Warp, Times television critic James Poniewozik argued that “the shift from network schedules to TV-when-you-want-it may change not just viewing habits but the whole culture of the medium.” Never mind the culture of television, I thought; with the demise of focal points like the thump of the morning paper on the doorstep and the six o’clock news, it is the culture of everyday life that has changed.

In fact, I wasn’t contemplating streaming at all when the week began. I was thinking about cable television. With the presidency of Donald Trump, the division of opinion in America has become profound. That’s obvious. I’m interested mainly in professional opinion, practitioners of all sorts – politicians and the journalists, film-makers, and scholars of contemporary affairs who cover and egg them on.

My conviction has long been that print newspapers continue to occupy the high ground of this community and likely will do so for many years to come. Myriad independent tributaries contribute to their deliberations, beginning with the online news services that have grown up to compete with them – giants like Bloomberg and Reuters, any number of startups as well, including ProPublica, Quartz and Axios. There are the usual suspects as well, naturally: magazines, book publishers, and, yes, the entertainment machine known as Hollywood. Even a stylized map depicting all these would-be narrators would take a double-double-double truck of newsprint.

Specifically, I have resolved to pay more attention to those with whose opinions I disagree That means editorial page of the WSJ in particular. I have been reading those pages for nearly 50 years, sometimes with admiration, sometimes with scorn, never with greater bafflement than today.

Why not, I decided, try to delineate a little more carefully positions they take that seem reasonable to me, the better to recognize and perhaps understand those that do not? To this end, it has seemed for some time that I should begin watching the Friday night edition of the Journal Editorial Report on Fox News, in hopes of getting a peek behind the scene.

So last week I ordered its basic cable TV package from my Internet service provider, only to discover that its 57 channels contained in the bundle included only five of any interest to me (ABC, CBS, NBC, Fox, and PBS), and none of the new news services that I craved: Fox News, CNN, MSNBC, and ESPN.

And that is how I became acquainted with the world of streaming. I read the Times section on “The Future of Streaming,” It turned out that I didn’t understand streaming at all. I knew that other people, chiefly the young, had long since ceased to deal with the cable television companies. I knew, too, that Comcast and GE had bought the giant content producers NBCUniversal (though I clearly didn’t understand why).

Finally I understood that I didn’t have to deal with the cable companies, either. I could turn my attention to their internet-based competitors, By then, however, I was on the way to the airport, out of time, if not endurance. I put off the search until I returned from out-of-town meetings.

Meanwhile, as a hedge, I invested in a copy of Great Society: A New History, by journalist Amity Shlaes (HarperCollins, 2019). Shlaes is the author of three well-regarded earlier books: Germany: The Empire Within (Farrar, Straus, 1991); The Forgotten Man: A New History of the Great Depression (HarperCollins, 2007); and Coolidge (Harper, 2013)

The book on Germany is, as I remember it, brilliant. The Forgotten Man and Coolidge. explorations of paleo-conservativism – counterfactuals in which the losers were the heroes – if only we had listened to them! The new book is an account of the beginnings of the “market turn,” at least in the US. That seems like something in which I might hope to identify plenty of common ground. It will take time. The book is 504 pages long. I plan to read every word.

. xxx

New on the EP bookshelf: Great Society: A New History, by Amity Shlaes (HarperCollins, 2019)

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column first appeared.

A face in the cloud

Featured sculpture by Carolyn Wirth in her show "Seeing Past Faces,'' through Aug. 20 at the Fruitlands Museum, Harvard, Mass., where she is artist-in-residence. The gallery notes say that she "blends images of her subject and photographs of herself in order to create an entirely unique facial structure.''