Aid to navigation

From the series “Another America,’’ by Philip Toledano. He’s in the group show “Artificial Intelligence: DisInformation in a Post Truth World,’’ at the Griffin Museum of Photography, Winchester, Mass. through Oct. 27.

Train at the Winchester MBTA station in October 2008, between the Town Hall and the First Congregational Church. Winchester is an affluent inner suburb of Boston.

The museum says the show focuses on how images inform, persuade and drive the conversation about critical thinking.

Moving to mellow

A portion of the north-central Pioneer Valley in South Deerfield, Mass., as it will look in several weeks.

‘Often seen, seldom felt’

A Field of Stubble, lying sere

Beneath the second Sun—

Its Toils to Brindled People

Its Triumphs—to the Bin—

Accosted by a timid Bird

Irresolute of Alms—

Is often seen—but seldom felt,

On our New England Farms—

By Emily Dickinson (1830-1886). See The Belle of Amherst a 1976 play based on her work.

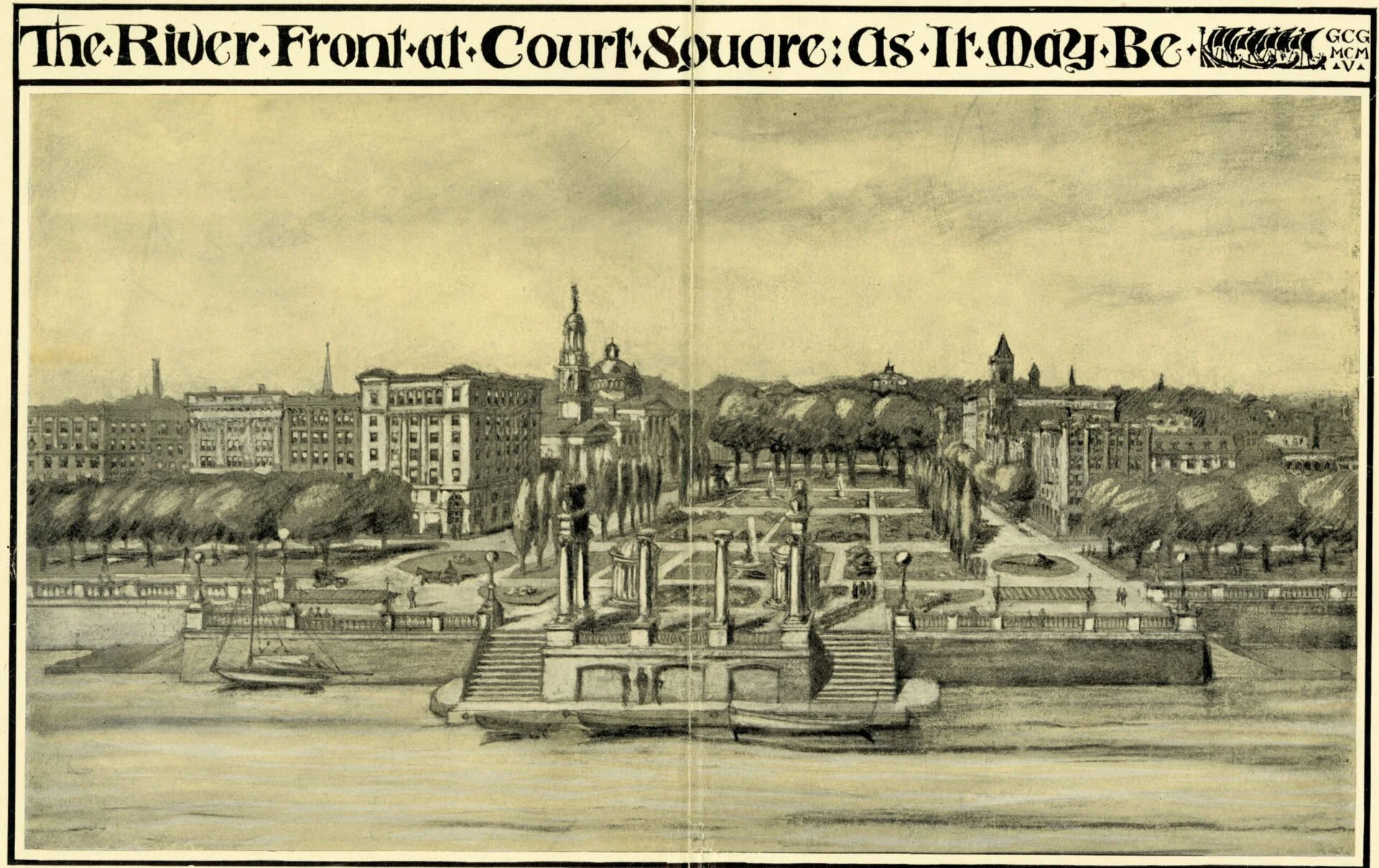

Designing Springfield's downtown through the years

From the “Designing Downtown” show at the Wood Museum of Springfield (Mass.) History through March 30.

The museum explains:

“Explore the history of downtown Springfield through centuries of plans that were never brought to fruition. Maps, drawings, blueprints, and more documents created by local citizens and nationally known city planners offer a glimpse into Springfield as it could have been and, at the same time, how the modern city came to be.

“Visitors can recreate a 1908 vote on the design of City Hall and can explore renowned landscape designer Frederick Law Olmsted Jr.’s plan for a ‘Washington Mall’-inspired design for Court Square in expanded detail using touchscreen technology. Visitors will leave the exhibition with a new appreciation for the shape of Springfield, with an eye towards its future development as the city continues to expand.’’

In a beautiful but sometimes grim region

“Pears,’’ by Audrey Shachnow, in the show’”, through Oct. 20, “Sculpture at The Mount’,’ the former (mostly) summer estate, in Lenox, Mass., in the Berkshires, of Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Edith Wharton (1862-1937). Ms. Wharton wrote a grim classic novel titled Ethan Frome about characters in the Berkshires.

The Mount staff says:

“‘Sculpture at The Mount’ showcases a diverse range of sculptures of varying scale and media produced by emerging and internationally established artists. This immersion of art in the natural world is free and open for the public to explore.’’

Liberate the fish? Keeping the pond less than ‘great’

Fish ladder, dam and waterfall at the Ipswich (Mass.) Mills Historic District, with mill pond, dating to the 17th Century, behind it.

— Photo by Mmangan333

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Here’s a quintessentially New England story about a heated debate in the Massachusetts North Shore town of Ipswich over whether to take down the Ipswich Mills Dam and fish ladder. The current dam was built in 1908, but there’s been a dam there since the 17th Century. It’s a reminder of the town’s industrial past. The idea, which seems to be supported by the majority of town residents, is to let the Ipswich River flow freely again, with associated environmental benefits, including better fishing and flood control.

But many love the pond that the dam created -- just to look at it and its waterfall, as well as for the skating and, I suppose, swimming, that it provided.

Lots of dams were built (and rebuilt) from colonial days to the early 20th Century to create waterfalls to power mills in New England towns large and small – at first to mill corn and for sawmills -- and many of us like those historic reminders, though few of the remaining mills serve any practical purpose anymore. But of course letting the rivers flow freely (when beavers allowed it), as they did when Native Americans lived along them, is much more “historic.’’

By the way, my parents lived for a few years on a mill pond in Norwell, Mass. The size of the pond could be adjusted by raising or lowering a board at the dam. The idea was to keep the pond at under 10 acres. If it got bigger than that, it would be classified under state law as a “great pond,’’ to which the public would have access.

The terror of making art

“The Pressure of the Blank Canvas,’’ by Duncan Reid, at SONO Arts Space at Norwood (Mass.) Arts Center June 16.

The astonishing Norwood Memorial Municipal Building.

— Photo Daniel P. B. Smith

Colors at Walden Pond

“Blue Water” (oil on canvas), by Patricia Crotty, in her show “Sky Water: Reflections on Walden Pond”, at Walden Pond State Reservation Gallery, Concord, Mass., through April 30.

The gallery says:

“The colorful abstract paintings and collages of local artist Patricia Crotty are inspired by the connection with nature that Walden Pond {made internationally famous by Henry David Thoreau’s book Walden} provides visitors. They celebrate the beauty of nature in all of its forms and seasons. Co-sponsored by Friends of Walden Pond. The exhibit is free; parking fees apply.’’

Perspectives on transparency

“Transparency’’ — a show by members of New England Wax

May 21 – June 27, 2024

Wellfleet Preservation Hall

335 Main Street in Wellfleet, MA

Reception: Saturday, June 1, 5–7pm

Open to the public Tuesday – Friday 10am–4pm, and during events.

Transparency, featuring works from 27 artists, seeks to investigate the concept of transparency in all its forms. Wax is a mutable material, capable of changing its form and adapting to its environment. Utilizing light, texture, form, and color, works in this exhibition play with the literal qualities of transparency, with pieces that are both ethereal or illusory and grounded in the physical world. Others explore the metaphorical dimensions of transparency, examining issues of trust, accountability, and communication. Through the works of a range of artists working with wax, the exhibition invites viewers to reflect on the significance of transparency in our society and explore its relationship to power, communication, and the human experience. Each piece in the exhibition offers a unique perspective on transparency and its many layers of meaning, creating a cohesive and thought-provoking narrative.

Wellfleet Preservation Hall is a vibrant cultural center that uses the transformational power of the arts to bring people together and impact positive change. It is a community center that celebrates people from all backgrounds and walks of life.

335 Main Street, Wellfleet, MA • 508-349-1800

Exhibiting Artists:

Katrina Abbott

Lola Baltzell

Edith Beatty

Hilary Hanson Bruel

Lisa Cohen

Angel Dean

Pamela Dorris DeJong

Heather Leigh Douglas

Hélène Farrar

Dona Mara Friedman

Kay Hartung

Anne Hebebrand

Sue Katz

Janet Lesniak

Ross Ozer

Deborah Peeples

Deborah Pressman

Stephanie Roberts-Camello

Lia Rothstein

Melissa Rubin

Ruth Sack

Sarah Springer

Donna Hamil Talman

Marina Thompson

Lelia Stokes Weinstein

Charyl Weissbach

Nancy Whitcomb

Slow, but no fossil-fuel emissions!

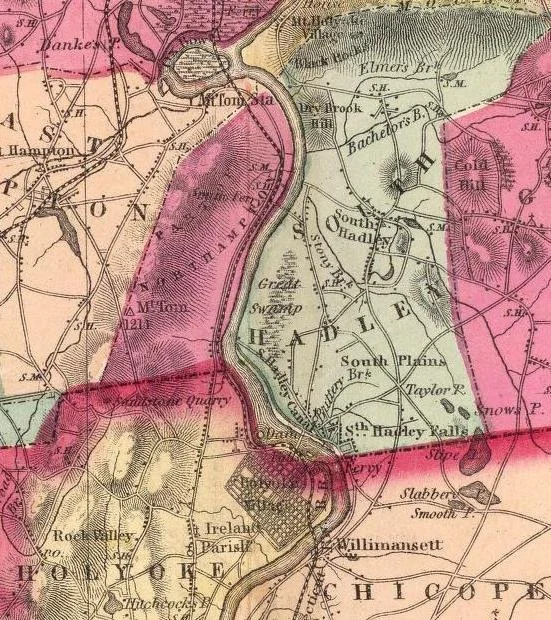

Map of South Hadley Canal, the earliest such commercial canal in the U.S. It was opened in 1795 and was closed in 1862 because of competition from railroads.

Timothy Dwight (1752-1817), who served as president of Yale (1795-1817), traveled through New England and New York beginning in the 1790s. The first volume of his four-volume account of his travels included this description of the South Hadley (Mass.) Canal.

About five or six miles above Chequapee [Chicopee] we visited South Hadley Canal. Before this canal was finished, the boats were unloaded at the head of the falls, and the merchandise embarked again in other boats at the foot.

The removal of this inconvenience was contemplated many years since, but was never seriously undertaken until the year 1792, when a company was formed, under the name of the proprietors of the locks and canals in Connecticut river, and their capital distributed into five hundred and four shares. . . .

A dam was built at the head of the falls, following, in an irregular and oblique course, the bed of rocks across the river. The whole height of the dam was eleven feet, and its elevation above the surface, at the common height of the stream, four. Its length was two hundred rods.

Just above the dam the canal commences, defended by a strong guard-lock, and extends down the river two miles and a quarter. At the lower end of the canal was erected an inclined plane. . . .

The outlet of the canal was secured by a sufficient lock, of the common construction. When boats were to be conveyed down the intended plane, they passed through the lower lock, and were received immediately through folding doors into a carriage, which admitted a sufficient quantity of water from the canal to float the boat. As soon as the boat was fairly within the carriage, the lock and the folding-doors were closed, and the water suffered to run out of the carriage through sluices made for that purpose. The carriage was then let slowly down the inclined plane. . . .

The machinery, by which the carriage was raised or lowered, consisted of a water-wheel, sixteen feet in diameter, on each side of the inclined plane; on the axis of which was wound a strong iron chain, formed like that of a watch, and fastened to the carriage.

When the carriage was to be let down, a gate was opened at the bottom of the canal; and the water, passing through a sluice, turned these wheels, and thus slowly unwinding the chain, suffered the carriage to proceed to the foot of the plane by its own weight. When the carriage was to be drawn up, this process was reversed. The motion was perfectly regular, easy, and free from danger. . . .

From Travels in New England and New York, Volume1, by Timothy Dwight

Remnant of the canal

Eat beef and melt

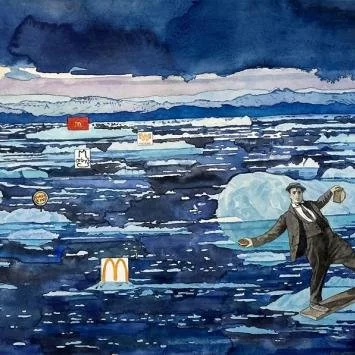

“Patty Melt” (watercolor), by Jane Goldman, in her show “Global Warming Series (2018-2023),’’ at Umbrella Arts Center, Concord, Mass., through May 5.

She explains:

“Global Warming Series (2018-2023)’’ is an ongoing series of watercolor monotypes on 22” x 30” Arches Hot Press watercolor paper. Dark humor sets the tone, inspired by silent-film comedians, especially the great Buster Keaton (above). In this context, the silent comedians represent all of us, experiencing global crises in slow motion. Like them, we watch the planet beset with catastrophe in ever faster motion.

“Some pieces in the series personalize the consequences of our behavior. The painting here depicts Keaton, burger in hand, amidst glacial melt, due in part to global beef consumption. Other works, such as ‘Clean Air Act,’ point out the obtuseness of ignoring our present reality. And in some works, such as ‘Teetering on the Edge,’ our Everyman is depicted in a situation right before catastrophe occurs, implying that there’s still time to alter the outcome.’’

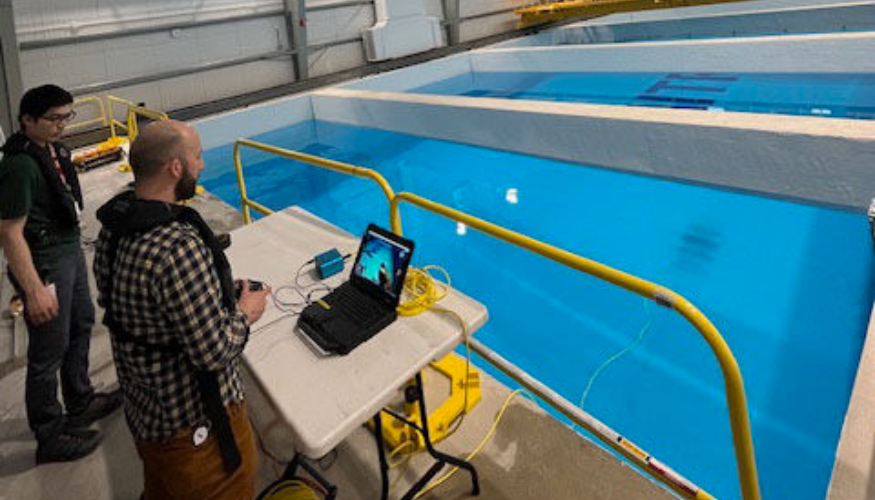

Mitre’s BlueTechLab

— Mitre photo

Edited from a New England Council report

BOSTON

“The nonprofit Mitre Corp. recently announced that a team from Chelmsford, Mass.-based product-development company Triton Systems Inc. has become the first commercial enterprise to use Mitre’s new BlueTech Lab for testing. The lab is at Mitre’s Bedford, Mass., campus and was built to support the company’s expanding marine-technology work. (Mitre is headquartered in Bedford and McLean, Va.) The lab incudes a 620,000-gallon test tank (above) that can be used to study communication and acoustic sensing on uncrewed undersea and surface vehicles.

“Triton Systems used the lab’s test tank to analyze the behavior of a small vehicle they are developing for a Department of Defense client. Angelica Cardona, a Triton engineer, had told Mitre that her company was eager to use the lab because of its ample workspace and controlled atmosphere.

“‘Being here saves us so much time and money. Without this resource, we’d be dealing with the logistical burden of getting out to sea and testing in mucky waters,’ said Cardona.’’

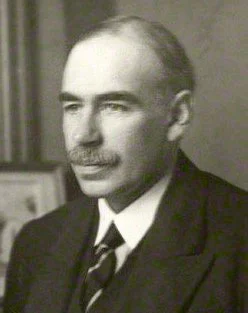

David Warsh: The outside helpers who helped make Keynes and Friedman iconic

John Maynard Keynes (1883-1946).

Keynes was a key participant at the Bretton Woods conference, which lay the foundation for much of the world’s financial system after the devastation of World War II.

The conference took place at the Mount Washington Hotel. Clouds here obscure the summits of the Presidential Range.

— Photo by Shankarnikhil88

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

John Maynard Keynes and Milton Friedman traveled different paths to become the dominant policy economists of their respective times. In The Academic Scribblers, in 1971, William Breit and Roger Ransom invoked the motto of the Texas Rangers to explain Friedman’s success: “Little man whip a big man every time if the little man is right and keeps a’comin’.”

But there was more to it than that.

Both Keynes and Friedman were slow starters and late bloomers. “It was The Economic Consequences of the Peace [in 1919] that established Keynes’s claim to attention”, as biographer Robert Skidelsky wrote at the beginning of the second volume of his trilogy. In murky circumstances, the prescient warning about the hard terms imposed on Germany after World War I failed to be recognized with a Nobel Prize for Peace, as Lars Jonung has shown. Not until 1936, with the appearance of The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money, when he was 58, did Keynes acquire the sobriquet that Skidelsky confers on him in that second tome, “the economist as savior.”

Friedman was 50 when, in 1962, he published both Capitalism and Freedom and, with Anna Schwartz, A Monetary History of the United States 1867-1960. He was nearly 40 when he turned to monetary theory. Within the profession he enjoyed growing success in the ‘50’s and ‘60’s. But vindication and celebrity waited until 1980, when he turned 69, as Federal Reserve Board Chairman Paul Volcker battled inflation under a monetarist banner; when Friedman’s television series Free to Choose, with his economist wife, Rose. was broadcast on America’s public network; and when Ronald Reagan was elected president.

Both Keynes and Friedman freely offered advice to American presidents, which only enhanced the economists’ stature. Keynes, at arm’s length, disparaged Woodrow Wilson; encouraged Franklin Roosevelt, whom he admired, and, 15 years after his death, saw his policies adopted by John F. Kennedy. Friedman, after a 1964 unsuccessful campaign with Barry Goldwater, enjoyed considerable influence with Richard Nixon and Reagan.

So, how did the Keynesian Revolution roll out in America? There are many accounts of the process by economists, but only one by an economic historian of how America’s leading most trusted newspaper columnist first resisted, then was convinced, and facilitated the movement’s acceptance for the next 40 years. (Michael Bernstein’s A Perilous Progress: Economics and public purpose in twentieth century America (Princeton University Press, 2001) surveys the period from a somewhat different angle.)

Walter Lippmann was already America’s foremost public intellectual, a common enough species today, but then more or less one of a kind. He published A Preface to Politics a year after graduating from Harvard College, studied Thorstein Veblen and Wesley Clair Mitchell, made friends with Keynes when both attended the Versailles Peace Conference, in 1919, compared notes with U.S. presidents, Supreme Court justices, scientists, philosophers, central bankers, lawyers, corporate leaders and Wall Street financiers.

Lippmann began writing an influential newspaper column in the Depression year of 1931. For a taste of how different that world was from our own. I recommend a viewing of Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane. In Walter Lippmann: Public Economist (Harvard, 2014) the late Craufurd Goodwin, of Duke University, traces the twists and turns of Lippmann’s columns as he sorted through various explanations of the Great Depression – too much free trade, too little gold, too many monopolies, unbalanced budgets, before becoming convinced that more public public spending was the key to recovery.

After World War II, Lippmann grew close to MIT’s Paul Samuelson. He tracked the debates of emerging “neo-liberal” factions, including leaders F. A. Hayek and Friedman, but declined to join the Mont Pelerin Society. His influence as a columnist finally came to grief over his prolonged support for the War in Vietnam, and he died, at 85, in 1974.

The sources of Friedman’s support are more complicated. Within the profession he had many key allies– his Rutgers professors Arthur Burns, later chairman of the Federal Reserve Board, and Homer Jones, later research director of Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; his graduate school friends, George Stigler and Allen Wallis; his brother-in-law Aaron Director, later dean of the University of Chicago’s Law School; his co-author Anna Schwartz; and, of course, his wife, economist Rose Director Friedman, to name only his closest associates. These were among his fellow Texas Rangers.

It has been Friedman’s acolytes outside the profession who were quite different from those of Keynes. The story of the law and economic movement has been well told by Steven Teles in The Rise of the Conservative Legal Movement: The battle for control of the law. On the financialization of markets, no one has yet topped Peter Bernstein’s Capital Ideas: The improbable origins of modern Wall Street. Friedman’s contribution to globalization is discussed in Three Days at Camp David: How a secret meeting in 1971 transformed the global economy, by Jeffrey Garten. The story of various business anti-regulation and anti-tax lobbying groups can be found in Free Enterprise: An American history, by Lawrence Glickman

It’s not that economics departments weren’t also special-interest groups, but they are special interests of a different sort, organized as competitors, which permits swift reversals within the profession itself. Whether that is the case with the legal, financial, corporate, and media industries remains to be seen. Maybe; maybe not.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

Art for a rocky region

One of Natalie MacKnight's gouache paintings of a rock, in her joint show with Joyce McJilton Dwyer, “Rock, Paper, Lichen,’’ at 6 Bridges Gallery, Maynard, Mass., through Feb. 24.

— Image courtesy of 6 Bridges Gallery

The gallery says that MacKnight loves the "fusion of dynamic energy and quiet contemplation" in rocks.

Hit this link to read about the history of New England famous stone walls.

David Warsh: About the economics giant Milton Friedman

Milton Friedman in 2004.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

The appearance of a long-awaited biography of Milton Friedman (1912-2006) has afforded me just the opportunity for which my column, Economic Principals (EP), has been looking. Milton Friedman: The Last Conservative (Farrar, Straus, 2023), by historian Jennifer Burns, of Stanford University, offers a chance to turn away from the disagreeable stream of daily news, in order to think a little about the characters who have populated the stage in the fifty years in which my column, EP has been following economics.

None was more central in that time than Friedman. We first met in his living room, in April, 1975, on a morning when he and his wife were packing for a week-long trip to Chile. We talked for an hour about the history of money. I left for my next appointment. Eighteen months later, Friedman was recognized with a Nobel Prize. I have followed his career ever since.

Ms. Burns’s book is a thoughtful and humane introduction to the life of an economist “who offered a philosophy of freedom that made a tremendous political impact on a liberty-loving country.” Standing little more the five feet tall, Friedman managed to influence policy, not just in the United States, but around the world: Europe, Russia, China, India, and much of Latin America.

How? Well, that’s the story, isn’t it?

Friedman grew up poor in Rahway, N.J. His father, an unsuccessful merchandise jobber, died when he was nine. His mother supported their four children with a series of small businesses, instilling in each child a strong work ethic. Ebullient and precocious, Milton was the youngest.

A scholarship to nearby Rutgers University put him in touch with economist Arthur Burns, then a 27-year-old economics instructor, forty years later Richard Nixon’s chairman of the Federal Reserve Board. Burns took Friedman under his wing and pointed him toward the University of Chicago. He arrived in the autumn of 1932, as the Great Depression approached its nadir.

Ms. Burns unpacks and explains the doctrinal strife that shaped Friedman and their friends encountered there. They include Rose Director, a Reed College graduate from Portland, Ore., who, improbably in those hard times, had enrolled as a economics graduate student at the same time. The two became friends; they parted for a year, while Milton studied at Columbia University and Rose considered her options in Portland; then returned to Chicago, becoming a couple, as members of the “Room Seven Gang” in the campus’s new Social Science building. Other members included Rose’s older brother, Aaron, a future dean of the university’s law school; George Stigler, who would become Friedman’s best friend; and Allen Wallis, an important third musketeer.

Distinctly not a member of that gang of graduate students was Paul Samuelson, a prodigy who had enrolled as an undergraduate, at 16, nine months before Friedman arrived to begin his graduate studies. Already tagged by his professors as a future star, Samuelson was clearly brilliant, but impressed the Room Seven crowd as being somewhat toplofty.

All this, rich in details and explication, is but preface to the story. Ms. Burns follows the Friedmans to New Deal Washington, where they marry and work for a time; to New York, where Milton pursues a Ph.D. at Columbia and Rose drops out to start a family (neither undertaking turned out to be easy); to Madison, Wis., where the couple spent a difficult year while Friedman taught at the University of Wisconsin, before returning to wartime Manhattan, to be reunited with Stigler and Wallis, working at Columbia’s Statistical Research Group.

In 1945, the major phases of the story lay ahead: Friedman’s return to Chicago, to form a faculty group sufficiently cohesive to become recognized as a “second Chicago school,” significantly differentiated in important ways from the first; his embrace of monetary economics; his battles with other research groups seeking to shape the future of the profession. These included the Keynesians and organizational economists in Cambridge, Mass., the game theorists in Princeton, the mathematical social scientists at Stanford and RAND Corp., in California.

By 1957, Friedman had opened a political front. Lectures given at Wabash College in 1957 become a book, Capitalism and Freedom, in 1962. The book earned well, and the couple named “Capitaf,” their Vermont summer house for it. A Monetary History of the United States, with Anna Schwartz, all 860 unorthodox pages of it, appeared the same year. In 1964 Friedman was invited to become chief economic adviser to presidential candidate Barry Goldwater, much as Paul Samuelson had advised John F. Kennedy four years before,

The Bretton Woods Treaty, a hybrid gold standard arrangement negotiated in 1944, by Harry Dexter White and John Maynard Keynes, began to crumble; Friedman was ready with an alternative: flexible exchange rates determined in international currency markers. Distaste with the war in Vietnam exploded. Friedman proposed an all-volunteer army: that is, market-based wages for soldiers. Inflation grew out of control in the Seventies; Friedman had a ready answer, simply control the money supply. Just ahead are Margaret Thatcher, Paul Volcker, and Ronald Reagan. Free to Choose: A Personal Statement, by Milton and Rose Friedman, a 10-part public television series, appears in 1980, becoming an international best-seller, followed by a book.

But that is getting ahead of the story here. Ms. Burns relates all this and its surprising conclusion with grace and attention to detail. No wonder it took nine years to write! In the end it offers a seamless account. But in that very seamlessness lies a rub.

Ms. Burns is a cultural historian, concerned with rise of the American right, which in the 1950s seemed to come out of nowhere: The Road to Serfdom, by Friedrich Hayek (Chicago, 1944); Sen Joe McCarthy; the John Birch Society; God and Man at Yale: The Superstitions of “Academic Freedom” (Regnery, 1951), by William F. Buckley Jr.; The Conscience of a Conservative (Victor, 1960), by Arizona Sen. Barry Goldwater, and the subsequent Goldwater presidential candidacy, and all that. Goddess of the Market: Ayn Rand and the American Right (Oxford, 2009) was her previous book. She knows Friedman’s influence on economics was great – too great to cover adequately in her book. Even the subtitle raises more questions than the book itself can answer.

Therefore, as I continue to peruse Milton Friedman: The Last Conservative, I intend to write over the next nine weeks about nine different books, each of which covers some aspect of Friedman’s story from a different angle. Trust me, the story is worth it: you’ll see. Meanwhile, if you get tired of reviewing the last seventy-five years, there is always the dismal news in the newspapers today.

. xxx

In a rush last week to get something into pixels about the American Economic Association meetings in San Antonio, I committed an embarrassing error.

Michael Greenstone, of the University of Chicago, delivered the AEA Distinguished Lecture, not Emmanuel Saez. You can find “The Economics of the Global Climate Challenge” here. If you care about climate warming, or simply want a glimpse of where the economics profession is headed, Mr. Greenstone’s lecture is well worth the hour it takes to watch.

That the Princeton Ph.D. and former MIT professor is today the Milton Friedman Distinguished Service Professor and former director of the Becker-Friedman Institute adds authority to his message.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this column originated.

Hand language

“Rahimah Rahim,’’ by Massachusetts photographer Philip C. Keith, in the group show “Intercession ,’’at New Art Center, Newton, Mass.

Toxic status seeking

Sisyphus (1548–49) by Titian, Prado Museum, Madrid, Spain

An 1880 painting by Jean-Eugène Buland showing a stark contrast in socioeconomic status

Adapted from From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Police said that wanted-to-look-rich businessman Rakesh Kamal shot to death his wife, Teena, and daughter, Arianna, and then killed himself at their 27-room mansion in Dover, Mass., the state’s richest town, on Dec. 26. (This being America, he apparently had no problem obtaining an unregistered gun.)

The couple, both of whom were entrepreneurs in education-sector ventures, some of which went sour, were in deep financial trouble, especially after paying about $4 million for the estate, with a $3.8 million mortgage (!) in 2019, reported The Boston Globe. (Different media have somewhat different numbers for some of the Kamals’ finances; The Globe has done the most reporting on this so far.)_

As The Globe reported, the mortgage was supposed to have been repaid in full by February, 2021, but by then the Kamals still owed $3.6 million and hundreds of thousands of dollars in related real-estate costs. The Kamals, bailing hard, took out a second mortgage of about $1.5 million in 2022, but an outfit called Wilsondale Associates foreclosed on the property in December, 2022 , with the couple still owing $3 million. They were bankrupt, but they continued to live in the mansion, under some mysterious arrangement.

So the family was apparently under great stress – stress they put themselves into. (I also noted that Arianna, the daughter, was sent to the expensive and elite Milton Academy although the Dover-Sherborn School District is ranked among the best in the nation.)\

Anxiously trying to keep up with the Joneses – or the Bezoses – can all too often lead to disaster in our status-obsessed nation. Chasing the American dream can end in a nightmare. Paging Jay Gatsby and gold-gilded Donald Trump.

Of course, most people want to live well, and the “finer things in life” are nice to have. But a craving for luxury and social status can become imprisoning, too. If you want to live a manorial lifestyle, don’t trap yourself by trying to do it on a mountain of borrowed money.

It’s worth reading John Bogle’s (1929-2019) book Enough: True Measures of Money, Business, and Life. Mr. Bogle pioneered low-cost investing via the index funds of Vanguard Group, which he founded. While he died a rich man (with about an $80 million estate), he could have made tens of billions. Instead, he basically gave away his Vanguard Funds to its investors, and much money to various charities.

He lived in a modest four-bedroom house in a Philadelphia suburb, and often commented on the corrosive effects of status seeking and greed, and warned that many in the financial-services sector took more wealth from the American economy than they created.

A heavyweight character

Rocky Marciano (1923-1969) in about 1953. He was heavyweight boxing champion of the world in 1952-1956 and retired undefeated. He grew up in the old shoemaking city of Brockton, Mass.

Main Street in Brockton in the early 20th Century.

”I was on a plane with him one time when he was the champion. And of course coming from Massachusetts, Rocky Marciano was my favorite. You play your character and it isn't right to step out of it. You have to stay in that character….Rocky Marciano had such guts and heart. He was something special.’’

— Robert Goulet (1933-2007), Canadian-American singer and actor. He was a native of Lawrence, Mass.

Inherited from Bollywood

From “Artifice,’’ new paintings by Springfield, Mass., artist Priya N. Green, at the D’Amour Museum of Fine Arts, Springfield, through Dec. 31

She says that her “layered oil paintings explore ideas of reality and perception through the pervasive images found in the news. Green’s work forms a response to the phenomenological impact of absorbing information and seeking truth through the screen. She uses the materiality of paint to address the veracity of the photographic images that have penetrated the twenty-first century psyche. As the granddaughter of a Bollywood screenwriter, Green believes her fascination with images is an inherited trait. By extracting and manipulating these images through paint, she forms an emotional connection to these events that are otherwise intangibly experienced through a screen.’’

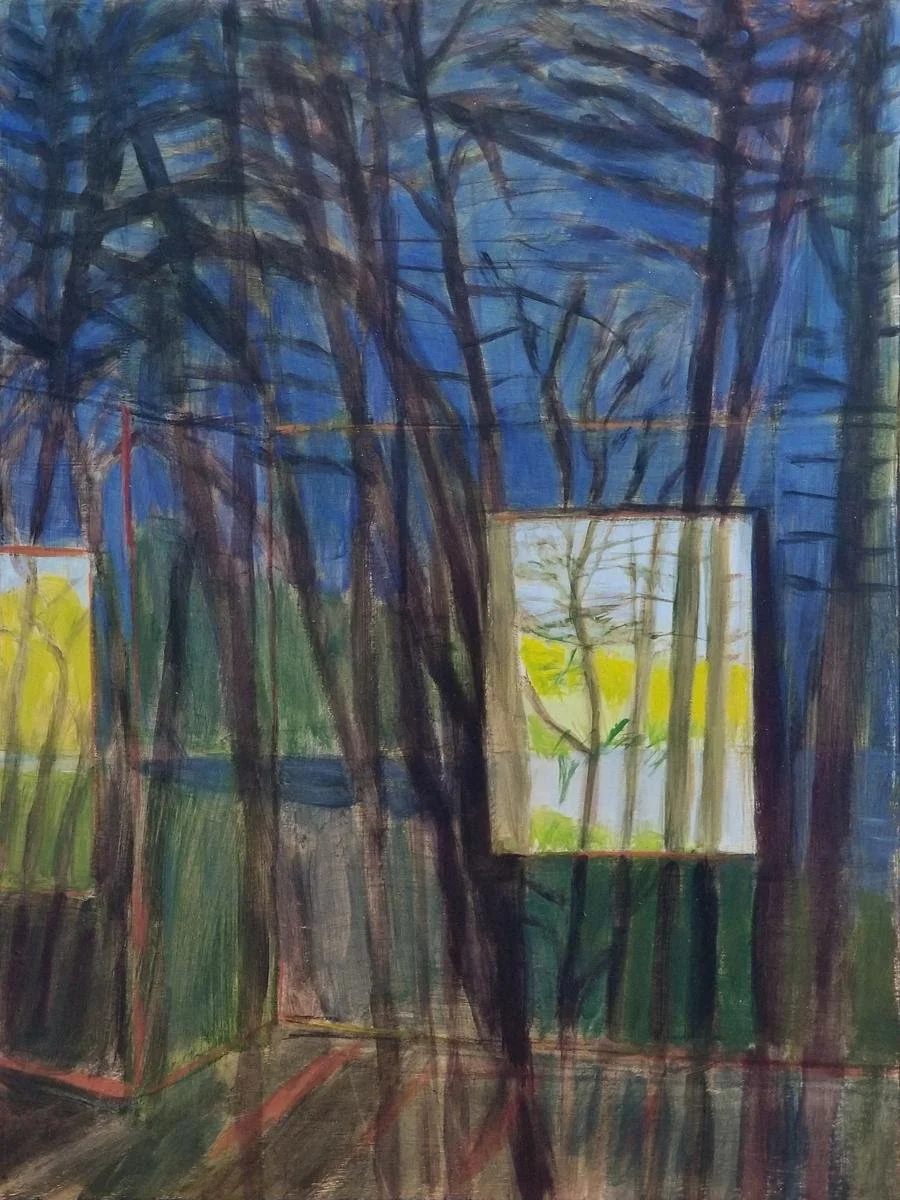

The trees that remain

‘‘Outside In” (acrylic on panel), by Concord, Mass.-based artist Irene Stapleford, in her show “Sightlines,’’ at Galatea Fine Art, Boston, Nov. 30-Dec. 31.

She says:

"From my modest home of more than a decade, I've appreciated the opportunity to observe and record some of my neighborhood's sightlines in paintings. Wildlife and trees, views of the nearby pond, and quiet peacefulness have reigned — until recently.

“Tremendous upheaval in my immediate surroundings has infused my plein air painting documentation with new urgency. Amid tree clearing, land excavation and construction activity adjacent to my home, I have continued to observe and paint. Many trees I've studied remain, but some are gone, cut down in their prime to make way for large new residences.

“As I experience these changing sightlines, the trees which remain have become my focus thanks to their steady, enduring, majestic and graceful presence.’’