Gerald FitzGerald: My wild ride on a Dukakis campaign

Michael Dukakis in 1984

At nearly one in the morning, two sets of three males paced the sidewalk in front of Phillips Drug Store at the corner of Charles and Cambridge Streets in Boston. It was 1982 in the heated Democratic primary race for governor. The youngish men were political enemies awaiting a delivery truck carrying the first edition of The Boston Globe. On the field for incumbent Massachusetts Gov. Edward J. King were Ed Reilly, political guru/re-election campaign manager; Gerry Morrissey, press secretary, and a factotum named Rick Stanton. Representing the challenger, once and future Gov. Michael S. Dukakis, were ace speechwriter Ira Jackson; deputy issues man Tom Herman and me, the Dukakis campaign press secretary. None of us spoke to any of them.

The bundles eventually dumped from the back of the truck were dragged inside and their cords cut. All six men scurried into Phillips to buy copies. Back outside, I had one Globe for us, holding it open while Jackson and Herman peered over my shoulders. Nothing on Page One! Nothing on the Metro cover! I slowly scanned succeeding pages until I found the story about our campaign besmirching Governor King’s wife. A freelance Dukakis supporter had bastardized a Jodie King radio ad to rearrange her statements as if she were answering a fictitious narrator's questions concerning her husband’s sexual preferences. Smiling broadly, I looked up at Morrissey:

“Inside. Page 19, below the fold,” I said with satisfaction.

Angry, Morrissey quickly moved toward me, thrusting an index finger close to my face:

“We’re going to get you!” he growled.

The doctored tape had arrived unsolicited in the campaign mail. I learned of it when John Sasso, Dukakis’s campaign manager, waved me into his office, grinning. We sat down and he began to play the offensively hilarious recording. Trouble was he had his telephone on speaker. Listening was a reporter from The Globe. I can’t recall clearly if it was Charlie Kenney or Ben Bradlee Jr. but I’m guessing it was Bradlee because my memory tells me that Sasso had first played it for Kenney alone and then again for me and Bradlee. I tried vigorously to stop the tape, but Sasso pushed me away. A brilliant man, John was making a mistake of earthquake proportions. He had grown close to several reporters. He treated them as buddies, expecting similar treatment in return. I had tried to convince Sasso that reporters were good people and fun to be around but they will eat you alive. A good story trumps a good “friend” any day.

The tape, we later learned, had been mailed in by an over-enthusiastic, brutally clever supporter from Ware, Mass., who supposedly used WARE’s radio facilities to create the satire. At the time I didn't even know where Ware was. As King’s campaign continued to work reporters to fan the fires of outrage, we Dukakis employees tried just as hard to hose it out of existence. Keeping what soon became known as “The Sex Tape” off the front page that first news cycle was a win for us good guys.

Earlier that day, Dukakis and I had met with the editorial board of The Patriot-Ledger at its old location in Quincy. The usual point of such meetings was to try to win a paper's endorsement, but the Patriot-Ledger’s policy was not to endorse any primary-election candidates. Dukakis still wanted to meet with them and answer their questions. Present were reporters and editors whose names I no longer recall. Near the end of the session someone entered the room and announced that there was a call for me that would be transferred to a telephone outside the door of the meeting room. I walked out and picked up the phone. Close by were wire-service teletype machines. These noisy, chattering tickers typed breaking news stories on a continuous roll of foolscap, sometimes preceded by dings whose urgency alerted staff to tear the stories off the roll to read.

It was Sasso on the phone. News of the Jodie King tape was out. He asked if the Patriot-Ledger knew this. Were they grilling Dukakis? I told him no. At the same time I turned to read the latest story coming in from Associated Press (or it might have been United Press International). It was all about the sex tape. I don't think I read the incoming story to John because that would have taken time I didn’t have. Instead, I told him that the wire service was breaking the story as we spoke. I turned around to face the newsroom. Glancing back at the machine, I noted where the story ended. Still holding the phone, I slid my left hand behind my back, ripping the paper from the teletype as silently as possible and brought it up under my suit jacket, shoving the paper down between my underpants and trousers.

Minutes later, the Duke and I were back in the car with a waiting driver. If anyone heard the crinkling sound as I scooted onto my seat, he was too polite to comment. They dropped me at campaign headquarters, and Michael went on to Springfield as scheduled.

That night, in the words of Ira Jackson quoting The Godfather script: “We hit the mattresses.” The telephones blazed for a couple of hours. After having been told that all copies of the errant tape had been destroyed, I told Frank Phillips: “The tape does not exist.” Phillips, writing for The Boston Herald, was someone I knew well and had once worked with on a journalism project. He didn’t ask if the tape had ever existed. Yes, I know – I am not proud of myself, then or now.

We went on to beat King by about seven points and defeat Republican John Sears by about a 59-38 percent margin in the general election. Although Dukakis eventually offered me his top press job, I stayed only a couple of weeks after the inauguration, which was on Jan. 6, to help with his transition. It’s one thing to work your heart out for low pay six or seven days a week all year to get your candidate elected. It’s another thing to have to go home for Thanksgiving not knowing if you've got an offer for a job to start in January. I never knew why the offer took so long, but I did learn that a paid campaign media adviser was pushing hard to clip me on behalf of his friend, an editor of an alternative weekly newspaper. Sasso is the one who told me, but advised me not to worry. When I told the Duke that I wouldn't stay he took me to lunch to talk me out of leaving. He even asked if he could meet with my wife to tell her why he wanted me. No way, I replied, she might cave. Dukakis asked me to recommend a replacement. In turn, I asked Frank Phillips. He suggested someone. To ice the interloper, I strongly recommended Frank's candidate, Jim Dorsey, who got the job.

Six years later Dukakis was serving his third term when he was nominated for president at the 1988 Democratic National Convention, in Atlanta. Sasso had run this campaign, too, until he hit a severe bump in the road five months before the convention. This time it was a videotape.

Then Delaware Sen. Joseph Biden, a primary competitor, had made himself vulnerable by delivering public remarks plagiarized from a British politician. Sasso leaked to the press a video comparison of the Biden speech with that of the Brit’s. It was enough to kill Biden's 1988 candidacy. But the public blow back was sufficient to make Sasso resign his own position at the end of September 1987. Still, I didn’t see a thing wrong with Sasso's action. While on a lunchtime walk up Beacon Street in front of the State House I learned from Mike Macklin, a TV news reporter, that Sasso was out. Macklin wanted me to comment since he knew that I had worked closely with John. I told Macklin on camera that Sasso should not take the fall for pointing out the truth and, further, that “I think he's being crucified.”

Years later, John's wife told me that during the Atlanta convention she and her husband dined with a group of national network newsmen. Speaking of his resignation Sasso told the gathering: “When I left the campaign only two people went on television to defend me – then New York Gov. Mario Cuomo and Jerry FitzGerald,” His listeners chewed their food, nodding their heads, until one, Tom Brokaw, I think, asked: “Who's Jerry FitzGerald?”

A year after the Biden tape debacle, about two months before the national election, Dukakis brought Sasso back to run the campaign as “vice-chairman.” John called me, I want to say, on Friday, Sept. 10. We met early next morning at the old Statler Building (now the Park Plaza) in Park Square, the same headquarters location used in 1982. After a brief chat I offered to help him any way he thought I could. Sadly, he declined.

“No, Fitzie. We're going down. What's worse is that we are going down never having stood for anything.” John's words cut me like a sharp knife. Even now, decades later, I find it extremely difficult to believe that he believed what he said.

Afterward followed one of my most enjoyable afternoons ever. Someone, I think on the side of the family of Sasso’s wife, Francine, was in town from New Hampshire with Red Sox tickets. John, the N.H. relative, and -- a surprise to me -- Ted Sorensen and I took a cab to Fenway Park to watch the Sox lose a close one to, as I recall, Cleveland. The seats were good, but sitting next to Sorensen made mine even better. I hardly let him shut up about his nearly 11 years as JFK's right arm, including writing speeches for the president whose phrases still ring in our hearts. In fact, we continued to chat walking all the way back from the stadium to Park Square. He was only 50 then. He would live another 22 years, but I never saw him again.

As we all parted, I clasped his hand and thanked him profusely for all he had done to help our president who had truly helped our nation. For much of my boyhood I had read books by Sorensen, Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr., Pierre Salinger, Arthur Krock and many others while daydreaming of assisting a worthy candidate to become president of the United States. That never happened for me. Still, sometimes the dreaming and the reaching out are nearly enough.

Gerald FitzGerald’s career has also included being a newspaper editor, a writer, a prosecutor, a defense lawyer and a civic leader.

Longing for 'The Comet'

If only…

The old New Haven Railroad put a unique three-car articulated high-speed passenger train called “The Comet’’ into service between Boston and Providence during 1935. The radically streamlined train was designed and built by the Goodyear-Zeppelin Company using the latest aerodynamic methods and technologies. Unfortunately, the speedy Comet was a bit too successful on the Boston-Providence run. When the New Haven's passenger business picked up at the start of World War II, the small train couldn't handle the crowds of people who wanted to ride it. The Comet was taken off the Boston-Providence run and spent the remainder of its service life on short-haul commuter runs in the Boston area. It was scrapped in 1951.

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal 24.com

It’s too bad that the Rhode Island Department of Transportation decided not to have a second set of tracks laid for the new Pawtucket commuter rail station and instead is building the station directly along Amtrak’s very busy Northeast Corridor tracks. As The Providence Journal’s Patrick Anderson reported in an Aug. 26 story (“Pawtucket station cost climbs to $51 million’’), “With the station directly on the Northeast Corridor, intercity or express trains couldn’t overtake trains stopping in Pawtucket.’’ That may well slow down traffic on that very heavily traveled Amtrak/MBTA line. And, Mr. Anderson noted, “ot building a second set of tracks could make it more difficult to create a Rhode Island-run rail shuttle.’’

The Transportation Department’s decision to forgo the tracks was done to save money but the project has included a hefty cost overrun -- $11 million so far -- at least in part because, Mr. Anderson reports, Amtrak rules (it’s their track!) “have forced the station work to be done at night and at other times of light traffic,’’ driving up costs. But the biggest false economy in this is for the long-term.

Of course, Amtrak itself needs more tracks to allow more and faster trains and help get as many vehicles as possible off the roads.

xxx

Kudos to Rhode Island Gov. Gina Raimondo and Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker for making a push for MBTA express trains between Boston and Providence. But this will require working it out with Amtrak, which runs on the same line. Again we need more tracks!! And an express train program may also require leasing electric-powered trains from Amtrak; the diesel trains now on the MBTA’s Providence-Boston route are less reliable than electric ones.

What could happen faster is having express highway lanes on highways in and around Boston that drivers would have to pay a toll to use. That would bring in money for transportation projects and encourage use of mass transit. Mr. Baker seems to like the idea, though many will yelp. But the region’s highway-congestion crisis has reached the point that strong, perhaps politically unpopular measures must be taken – and soon. (Some wags are calling the proposed express lanes “Lexus Lanes,’’ implying they’ll unduly favor richer folks who can more easily afford them.)

Michael Dukakis, the 1988 Democratic presidential nominee, former Amtrak chairman and now a Northeastern University political science professor, said at a Grow Smart RI meeting in April:

“The only way to solve this congestion problem is to have a first-class regional rail system not only for Massachusetts but for all of New England, with the six governors deeply and actively involved. It would take 60,000 to 70,000 cars off the road every day.”

Dukakis keeps going

Michael Dukakis.

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Whatever you think of the politics and policy positions of former Massachusetts Governor and 1988 Democratic presidential candidate Michael Dukakis, his sterling character and concern for the common good are unassailable.

Consider that at 85, he still shows up at such events as a Massachusetts Department of Transportation meeting on Nov. 19 to present a report touting a long-proposed rail link between Boston South and North stations, which would speed up travel throughout eastern New England. At such meetings he patiently waits his turn to speak.

He displayed such patience – and deep policy knowledge and commitment -- even when he was governor. He has always been much more than a politician; he’s a devoted public servant.

The Boston Globe reports that he told the attendees: “It’s inconceivable to me that we are going to deal with congestion problem of ours without getting cracking in a hurry on a first-rate regional rail system.’’ At 85, still looking ahead.

MBTA commuter rail map as of 2018 showing separation of northern and southern segments. Amtrak's Downeaster connecting with Maine terminates at North Station; all other Amtrak trains terminate at South Station.

James P. Freeman: Michael Dukakis: The last traditional progressive

Beaming over the convention of the consonant caucus, the speaker uttered what would be the second most memorable line in the 1988 presidential race: “This election isn’t about ideology, it’s about competence…” This dramatic statement was later bested by George H.W. Bush’s “read my lips…” tax pledge.

Atlanta’s Democratic National Convention that July proved to be, in retrospect, the last stand for Michael S. Dukakis, the last traditional progressive. As progressivism gallops to a new beat of populism, modern-day revivalists should look to Dukakis as their godfather.

He is last major living link to the progressive forefathers. Born in Brookline in 1933, he was also born into the first progressive era of Presidents Roosevelt, Wilson and Roosevelt. It would mark the first time the republic would rely upon government, not self-sufficiency, for sustenance, emblematic of modern times.

Citizens needed progress up from the Founders’ ideas. A strong central government, believing in its boundless abilities, could master public and private affairs, thereby delivering happiness. The Constitution was inelastic; its limitations were to be disdained as impediments to the very progress government sought to engineer. Politics became a science.

Dukakis’s long career in public service is writ large with progressive themes. In 1965, as a young Massachusetts state representative, he introduced a measure to legalize contraceptive use for married couples, an early imprimatur of his activism. For the commonwealth’s conservative Catholic bloc in the House, however, voting on birth- control laws written by Protestants in the 1890s proved to be controversial and complicated. Boston's Cardinal Richard Cushing, remarkably, advised its members in the legislature: “If your constituents want this legislation vote for it. You represent them. You don’t represent the Catholic Church.” The bill passed.

Arguably, this episode — more than John F. Kennedy’s 1960 election to the presidency — helped convert a majority of Catholics from Republicans to Democrats in Massachusetts. Suddenly, it seemed, culture impacted Catholic politics as much as theology. Those majorities remain intact today. Dukakis was elected to the first of three terms starting in 1974 and he remains Massachusetts’s longest-serving governor.

His first attempts as a reformer were rebuffed and he lost the 1978 primary. Not nonplussed, he was reelected in 1982 with an even more robust belief in government’s efficacy.

He originally opposed the initial concept of the Central Artery/Tunnel project in Boston but expanded its scope to accommodate business and government interests. Boston’s Big Dig cost nearly $4 million a day at its peak. Initially a $2.2 billion expenditure in the early 1980s, final estimated outlays are $22 billion, to be paid off in 2038. The administration of this public-private partnership exposed a skewed risk-reward model (socializing losses, privatizing profits).

Under his leadership, after delays and denial for exemption, Massachusetts was found to be in violation of the landmark Clean Water Act. Every day 100,000 pounds of sludge and 500,000 gallons of barely treated wastewater were dumped into Boston Harbor. A federal court, not political epiphany, ensured the cleanup.

Former EPA Administrator Michael Deland said that the commonwealth’s willful disobedience was “the most expensive public policy mistake in the history of New England.” Raw sewage stopped flowing into the nation’s oldest harbor in September 2000.

Dukakis in 2009 reflected on “two of the biggest projects in history at the time.” The harbor restoration — mandated, mind you — “came in on time and 25 percent under budget.” Of theBig Dig, he said: “We all know what happened with the other.”

The difference? “It was about competence of the people running the projects…”

Few remember that Al Gore (not the elder Bush) first raised the weekend-furlough matter during the presidential primary. Dukakis vetoed a bill in 1976 that would have denied murderers, like Willie Horton, such freedom. The program was ultimately abolished after questions were raised about criminal rehabilitation.

Before there was Obamacare and Romneycare there was Dukakiscare. He signed into law the nation’s first universal healthcare insurance program in 1988. A tiny Republican minority quietly disrupted its funding, leaving it an obscure footnote to history.

At 82, still residing in Brookline, still a progressive sanctuary, Dukakis leaves a lasting legacy. He has affected the lives of more residents in Massachusetts than anyone in a century. Clearly, that is a triumph of ideology over competence. As government at all levels struggles with executing competent stewardship, people should look at Dukakis in another light. He at least addressed competence as a core competency.

New-fashioned progressives have abandoned it.

James P. Freeman is a New England-based writer for the New Boston Post. and a former columnist with The Cape Cod Times.

Jim Stergios: Time to stop Boston mega-project mania

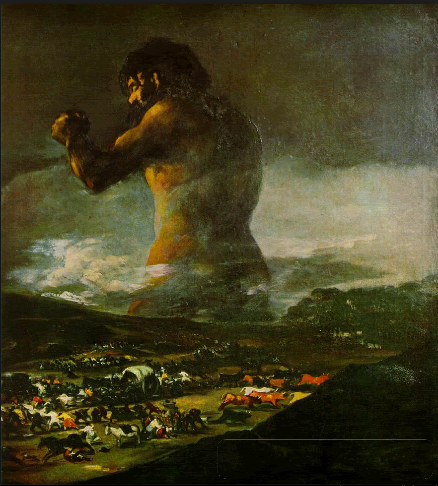

One of Goya's Titan paintings.

BOSTON

Last year it was a billion-dollar expansion of the Boston Convention and Exhibition Center, with an embedded $110 million giveaway to a hotel developer. This year it was the recently abandoned Boston 2024 Olympic bid. Now we’re talking about digging a tunnel to connect North and South Stations. Boston has a mega-malady, and it is a love affair with mega-projects.

Modern-day Massachusetts is acquiring a variant of French political sophistication, whereby Boston (Paris) is the showpiece and the rest of the state (France) is relegated to flyover status. Here are three quick facts to waken us from our dangerous flirtation with economic development in the grand continental style. The MBTA — buried under nearly $9 billion in debt and interest, and with a maintenance backlog of more than $7 billion — should focus on avoiding a replay of last winter’s horror story. A new tunnel does not make the MBTA’s list of top priorities.

Often lost in the heated discussions of particular parcels is the bigger question of what kind of a city we want to be. Cost realism has in the past reined in Boston’s appetite for megaprojects. In essence, that is what happened when the governor and legislative leaders commissioned a third-party evaluation of the Boston 2024 effort.

Former Gov. Michael Dukakis argues that the North-South Rail Link should be buildable for $2 billion, not the estimate of $8 billion. It should cost less, but it will cost more. We just learned that the Green Line extension is $1 billion over budget. No one has forgotten that the Big Dig was supposed to cost $2.8 billion, but ultimately broke the $15 billion sound barrier.

Cost estimates aren’t the only problem. Project benefits are routinely oversold. Exhibit A: The unrealistic pictures painted by convention center feasibility studies are legendary. The BCEC is doing between 30 and 40 percent of the business it was projected to do. Exhibit B: The Greenbush commuter rail line. Instead of, as projected, taking eight passengers off highways for each one lured from the MBTA’s South Shore commuter boat service, nearly half the current customers previously took the ferry. When those who rode other commuter rail lines are added in, more than 60 percent of Greenbush riders were already using public transit.

Rather than Boston’s mega-project megalomania, we need to return to a good old American sense of fair play. When Gov. Charlie Baker pulled the plug on the proposed BCEC expansion, he created an opportunity to do just that. Each year, tourism-related taxes generate tens of millions of dollars to underwrite the Massachusetts Convention Center Authority. Between now and 2034, these taxes will provide the MCCA with $30 million more annually than it needs to operate. After 2034, when the bonds sold to pay for the construction of the BCEC are paid off, that amount will more than double.

Anyone who has spent time in Massachusetts cities outside Boston knows that they have significant infrastructure needs, including roadways, retail spines, bridges, and sidewalks. For years the Big Dig left these cities starved of investment; it takes no sophistication to understand that the litany of Boston mega-project proposals would continue that trend.

Cost estimates aren’t the only problem.Project benefitsare routinely oversold. Infrastructure upgrades will not, by themselves, refashion the futures of Massachusetts’ cities. But together with reforms to public schools, policing, and economic policies, state investment can go a long way toward making them more attractive places to live and work. In fact, creating an infrastructure fund for these cities to leverage needed reforms would prove a powerful urban revitalization strategy.

Greater Boston needs its fair share of infrastructure investments — and right now MBTA upgrades are what can do the region the most good. State government must keep in mind, however, that more than half of the state’s population is outside Route 128. Forgoing an $8 billion Boston mega-project would allow infrastructure upgrades across Massachusetts.

Jim Stergios is executive director of the Pioneer Institute, a Boston-based think tank. This piece originated in The Boston Globe.

Watch Boston's nascent international think tank

Do think tanks really think? It's not that these organizations -- mostly centered in Washington, D.C., but also scattered across America – don't harbor some fine minds among their scholars and fellows, but the problem is that we know what they think -- and have often known for a long time. The rest is articulation.

Among Washington think tanks, we know what to expect from the Brookings Institution: earnest, slightly left-of-center analysis of major issues. Likewise, we know that the Center for Strategic and International Studies will do the same job with a right-of-center shading, and a greater emphasis on defense and geopolitics.

What the tanks provide is support for political and policy views; detailed argument in favor of a known point of view. By and large, the verdict is in before the trial has begun.

There a few exceptions, house contrarians. The most notable is Norman Ornstein, who goes his own way at the conservative American Enterprise Institute (##aei). Ornstein, hugely respected as an analyst and historian of Congress, often expresses opinions in articles and books that seem to be wildly at odds with the orthodoxy of AEI.

A less-celebrated role of the thinks tanks is as resting places for the political elite when their party is out of power. Former U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations John Bolton, rumored to be favored as a future Republican secretary of state, is hosted at AEI. National Security Adviser Susan Rice was comfortable at Brookings between service in the Clinton and he Obama administrations. At any time, dozens of possible office holders reside at the Washington think tanks, building reputations and waiting.

My interest in think tanks and their thinkers has led me to what might be developing into a think tank, although it's too early to say. It's so early that it has no headquarters, secretariat or paid staff. But this nascent think tank has gathered a loose faculty from a coterie of public intellectuals, mainly in and around Boston, and abroad in Hanoi, Tokyo and Berlin.

It's called the Boston Global Forum. Formed in 2012, it's led by two very different but, apparently, compatible men: Michael Dukakis, former Massachusetts governor and Democratic presidential nominee, and Nguyen Anh Tuan, who founded a successful internet company in Vietnam and now lives in Boston.

The concept of the forum is to study and discuss a single topic for a year. Last year, in forums and internet hookups between Boston and Asian and European cities, the topic was security in the South and East China seas, where war could easily erupt over territorial disputes. After a year of discussion, the participants concluded that a framework for peace in the region needs to be established and that current international arrangements and organizations don’t go far enough in that direction. This year’s topic is cybersecurity.

The Boston Global Forum has strong ties to the faculties at Harvard and Northeastern University, where Dukakis is a professor. Most forum meetings take place on the Harvard campus. Two of the forum's most conspicuous champions are Harvard Professors Joseph Nye and Tom Patterson. Patterson’s office at the John F. Kennedy School of Government serves as a kind of de facto headquarters.

This new entrant into the think tank cohort is very East Coast-tony, and very energetic. This year it has plans for meetings in Vietnam, Tokyo and somewhere in Europe, and has attracted such media heavyweights as David Sanger, of The New York Times, and Charles Sennott, one of the founders of the online GlobalPost.

As the Boston Global Forum is a new think tank, questions abound: Will it get funding? Will it find premises and staff ? Will it get public recognition?

The big question about anything that looks like a think tank is, will thinking happen there? Will the Boston Global Forum be a crucible for big ideas? Or will it, like other think tanks, develop its own binding ideology?

Will the Boston Global Forum become, like so many, a smooth propaganda machine? Or will it be a place where the outlandish can live with the orthodox?

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of “White House Chronicle” on PBS. His e-mail is lking@kingpublishing.com.

Robert Whitcomb: Republicans bother to vote

‘’The people have spoken … and now they must be punished.’’

-- New York City Mayor Ed Koch’s quip after an election loss

The politicians elected yesterday to new jobs will soon be blamed for doing the same sort of things that their ousted predecessors did as they tried to mate good governance with reality and ambition/ego with idealism.

Distracted and often ignorant citizens, many of whom are usually fleeing reality at a good clip, will demand a perfection from their elected officials that they would never demand of themselves. They will also praise, or more likely blame, the politicians for everything from the weather to the economy’s gyrations. (The first is out of politicians’ control --- unless you factor in the need for us to reduce the amount of carbon dioxide we’re pumping into the air. The second has so many global variables that government’s ability to manage economic cycles remains highly constrained.)

In its existential anxiety, the “the Public’’ will continue to depend on politicians to solve all its problems. Modern electronic media, with their instant ‘’analyses’’ and search for simple, vivid narratives, heighten this dependence and the resulting anger when public/personal problems aren’t immediately fixed.

Our news media (who roughly represent the citizenry’s character flaws) intensify our tendency to pour our hopes and fears into a few people, or even just one (especially the president). Such personalization is easier than trying to understand the details of, say, public policy, economics and history, let alone science.

My sense of the sloth of those who attribute all fault and praise in a big news event to one or very few individuals came together back in 1992, when President George H.W. Bush was in effect blamed for not restoring Dade County, Fla., to its pre-Hurricane Andrew strip-mall glory within 36 hours. Then in 2005, the public blamed his son for the Hurricane Katrina New Orleans mess, although that disaster was inevitable – New Orleans was/is a very corrupt, badly managed city most of which is at sea level or below.

And now some call the complicated (scientifically and otherwise) Ebola situation President Obama’s fault. (That his father was African may inform some of the attacks against him in this….)

Meanwhile, the public takes commands from the media and politicians about how they should feel. If the preponderance of the big (and small) media say that “Americans are pessimistic’’ or ‘’optimistic,’’ then we salute and feel accordingly, whatever the unemployment rate. But not for long, since the conventional-wisdom narrative can be changed overnight and the change “go viral.’’

That’s not to say that politicians’ characters and personalities don’t count – especially in great crises --- e.g., Lincoln in the Civil War or Churchill in the summer of 1940 as Britain stood virtually alone against the Nazi onslaught. But they rarely count nearly as much as we’d like to think they do. Life is far too complicated.

Now we look forward to more gridlock in Washington because the public doesn’t know what it wants (other than more services and lower taxes). It says “government doesn’t work’’ and ensures that it doesn’t by its conflicting and rapidly changing voting -- or, especially in a mid-term election, its nonvotes. The nonvoters are always among the biggest complainers.

Democrats have particularly little excuse for whining this year. A Pew Research Center survey shows that among those who were unlikely to vote last Tuesday, 51 percent favored Democrats and 30 percent the GOP. In this matter, Republicans are harder-working: They summon the energy to take 20 minutes to vote.

xxx

The lack of a direct long-distance rail connection between Boston’s South Station and North Station has always seemed to me ridiculous. Connecting them would make it considerably easier to move between southern and northern New England and further energize passenger rail as demographics (including a huge increase in the number of old people and a new propensity of younger people not to drive) makes public transportation ever more important.

The link should have been made at least a century ago. But the dominant New England railroads of the time – the Boston & Maine (at North Station) and the New Haven (at South Station) -- the city and the state’s couldn’t get it done, as it wasn’t done between New York’s Grand Central Station and Pennsylvania stations.

The Big Dig’s cost overruns haunt efforts to make this link. But rail projects make rich cities even richer by making them more efficient and attractive. The Big Dig made Boston more of a world city. Past gubernatorial foes Michael Dukakis, a Democrat, and Bill Weld, a Republican, recently joined to promote the link. All of New England will benefit if they succeed.

Robert Whitcomb is a Providence-based editor and writer and a partner in Cambridge Management Group (cmg625.com) a healthcare-sector consultancy. A former editorial-page editor for The Providence Journal and a former finance editor of the International Herald Tribune, he's also a Fellow of the Pell Center for International Relations and Public Policy and oversees this site, newenglanddiary.com