All the world's a shadow box

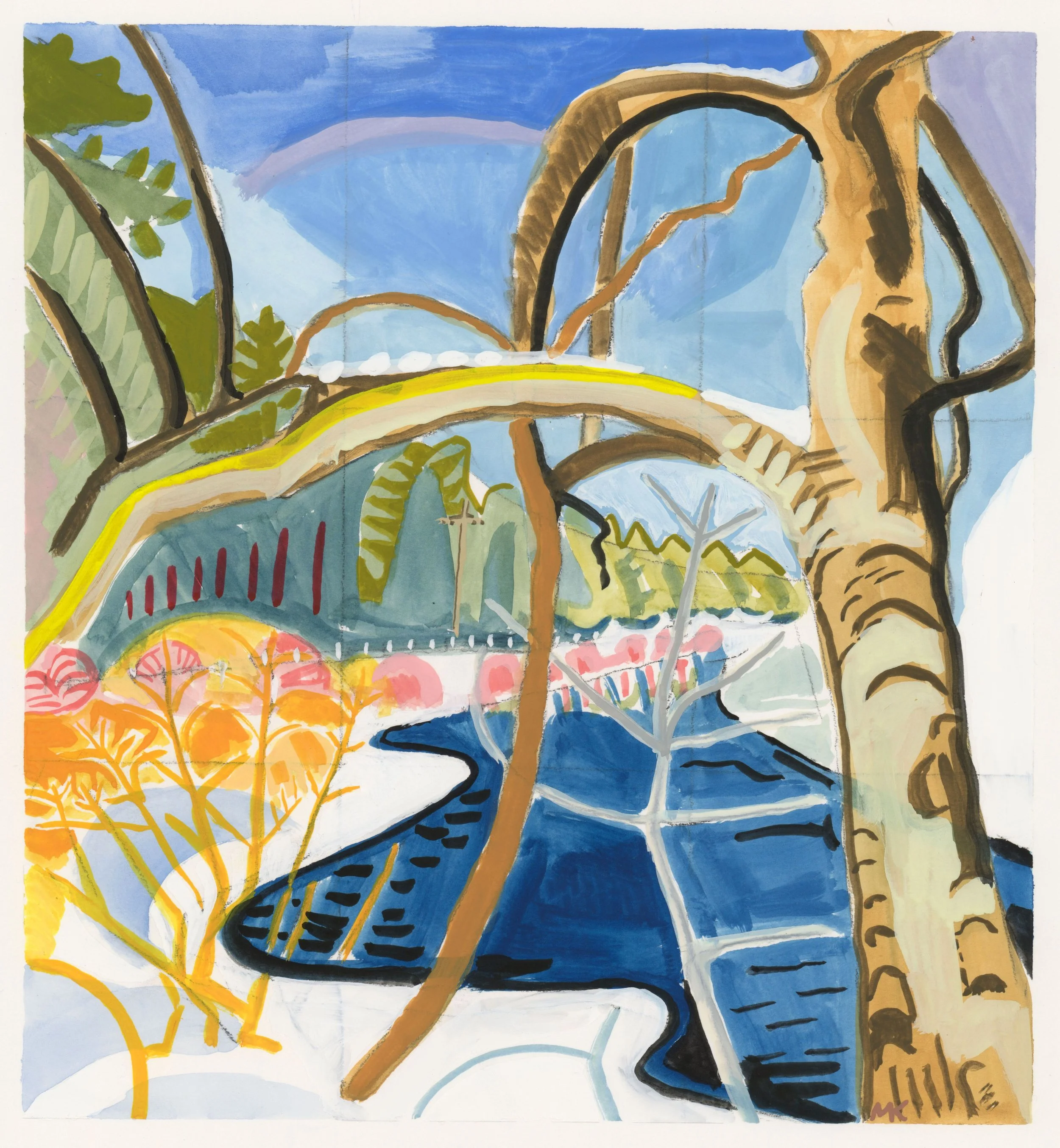

Work by Melora Kennedy at The Front gallery, in Montpelier, Vt.

The gallery says:

“Melora Kennedy is a painter who has also made shadow boxes, and is currently occupied with still life. Still life makes it possible to practice her art a little every day—which makes it like meditation. Setting up a still life is similar to arranging the elements inside a shadow box: it resembles child's play. She's drawn in by the way that plants, in particular, express human emotion in their every gesture. She tries to paint so this feeling of liveliness comes across.’’

Melora has been living in Vermont since 1998. She teaches at a nursery school and lives with her partner on some land that they garden together.

WPA art

"Skyscrapers” (circa 1937) (oil on canvas), by Joseph Stella (1877-1946), in the WPA Collection, at the T.W. Wood Gallery, Montpelier, Vt.

The Federal Art Project (1935-1943) was a New Deal program to fund America’s arts projects under the Works Progress Administration (WPA). It sustained some 10,000 artists during the Great Depression.

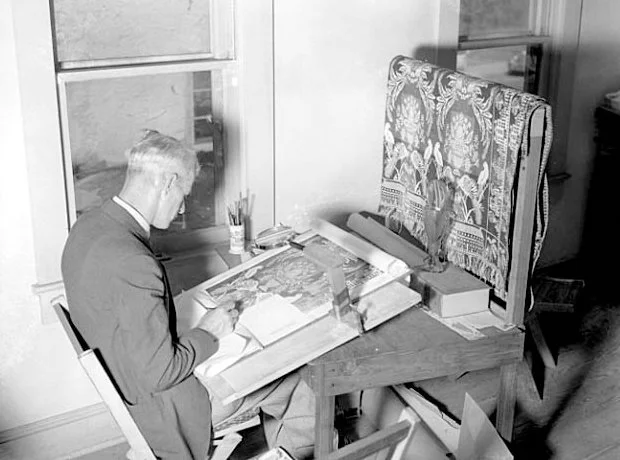

In 1940, Magnus Fossum, a WPA artist, copying the 1770 coverlet "Boston Town Pattern" for the WPA’s Index of American Design.

WPA Pump Station, in Scituate, Mass., built in 1938

Birchbark building

“Back of State and Main” (in Montpelier Vt.) (inkjet on birchbark), by Burlington, Vt.-based photographer Richard Moore, at The Front gallery, Montpelier, Vt., though Jan. 29.

Main Street in downtown Montpelier.

— Photo by GearedBull

Montpelier in 1884. Note the state capitol. The Winooski River enjoys flooding the city from time to time.

A start on the housing crisis

“Dream Home Dream” (exterior latex paint, plywood, metal, and chalk), by Rob Hitzig, in the group show “Exposed 2022’’, at The Current, in Stowe, Vt., through Oct. 22.

The gallery explains:

The show represents nine artists “in an outdoor sculpture exhibit sprawling across the streets of Stowe….'Dream Home Dream’ invites viewers to engage with the piece, covering it in chalk markings.’’

Mr. Hitzig is based in Montpelier, Vt.

Stowe Community Church

-- Photo by Terry Foote

State Street, in the Montpelier Historic District

— Photo by Georgio

From Marxism to the Burlington marketplace

Church Street Marketplace in Burlington

“‘People’s Republic

of Burlington,’ old Marxist

stronghold, now just a stage

on its way to high

capitalism. Church

Street commodified.

Out on the loop roads

of Montpelier, what does ‘strip

development’ strip? Grass

from pastures….”

— From “Hayden’s Shack I Can See to the End of Vermont,’’ by Neil Shepard (born 1951), a Johnson, Vt.-based poet

LeeAnn Hall: Build back public transit much better

A Green Mountain Transit Authority bus in Montpelier, Vermont’s capital

Via OtherWords.org

If you follow the news about President Biden’s Build Back Better agenda, you might have heard a lot about its 10-year price tag. But you probably haven’t heard much about what it would actually do.

The bill will invest in care for children and seniors, cover more health care under Medicare, make the tax system more fair, and address the climate crisis. Those parts get some coverage, and they’re all worth doing.

But there’s one key thing that’s gotten almost no attention: the bill’s historic investment in public transit. This would have a tremendous positive impact on communities across the country.

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has hurt millions of families and their communities in many ways. One essential aspect of community life that faced an existential threat was public transportation. Systems all over the country faced massive revenue shortfalls and budget cuts.

Previous COVID rescue packages helped public transit bypass disaster. But when it comes to transit — the lifeblood of many communities and a key driver of economic growth — just avoiding disaster is not enough.

The pandemic dramatically showed that transit is vital to our communities. Essential workers depend on and operate transit, small businesses depend on transit, and historically marginalized communities depend on transit.

Transit is a key component of a more environmentally sustainable society and the road to equity for disenfranchised communities — in rural, urban, and suburban areas like. In essence, public transit has a huge impact.

Which is why what Democrats in Congress are doing right now is so vital. When you combine the bipartisan infrastructure bill already passed by the U.S. Senate with the Build Back Better plan, it results in the largest ever investment in public transit in the nation’s history.

Investments in public transit create jobs and help connect people to more job opportunities. By one estimate, every $1 billion invested in transit supports and creates more than 50,000 jobs. The larger the investment, the more people benefit.

For years, lawmakers in Washington neglected funding for buses and trains while fueling highways and cars. The result has been a transportation system that is inequitable, unsafe, unhealthy and unsustainable.

It also stunted the economic contributions of too many people, particularly in rural communities and communities of color, at a time when we can’t afford not to give everyone an opportunity to get the jobs they want.

Congress and the Biden administration can reverse this trend.

The Build Back Better plan is so much more than the numbers and political gamesmanship that is covered on TV every night. It’s something that will make people’s lives better — including by rebuilding a transit system that allows more people to move freely within their communities.

Transit is essential. Transit is our future. Congress must pass the Build Back Better plan without delay. Our communities can’t afford to wait any longer.

LeeAnn Hall is the executive director of Alliance for a Just Society and director of the National Campaign for Transit Justice.

John H. Fitzhugh: A plan for America to reopen for business

Ironically, New York might be one of the first places to reopen for business in the COVID-19 pandemic.

President Trump has been widely criticized for expressing a desire that Americans return to work by Easter. He later modified his remarks to say that reopening of businesses would depend on such local factors as population density and infection rates for the COVID-19 virus.

I am a “Never Trumper” but in this case applaud the president for raising two critical issues: one, how we decide when to return to work, and two, the importance of work.

The current strategy of fighting this virus, based on current medical advice, is to distance ourselves from each other, thus “flattening the curve” of infection to better use our limited medical resources, such as hospital beds and ventilators. This approach, we are told, will lengthen the period during which people are at risk for infection but save innumerable lives.

Some areas of the country have been better at this than others or, because of population density, are simply already “socially distanced.” New York City, unfortunately, is not, it being one of the most densely populated cities in America. Its attack rate (ratio of those infected to those tested) is very high, which means that the infection period will be shorter but potentially more deadly than elsewhere in the U.S.

Ironically, this also means that New York City may be one of the first places that could reopen for business because most residents will have been infected and either recovered or unfortunately passed away.

But now let’s turn to the importance of resuming business, and how we decide to do so.

American business is, with some notable exceptions, closed for business. It is dead in the water, to use a nautical expression. Critical industries are still functioning, either with limited staffs or on-line, but most are idle. This is especially true of small businesses, retail shops and many service industries. My guess is that the gross domestic product (GDP) overall is not 20 percent of what it should be, or was before the virus shutdown.

Congress has passed legislation directing some $2 trillion to offset this shutdown. The Federal Reserve has made an additional $4 trillion available. This is the largest financial bailout ever and, it is said, will help for maybe “a few months.” In my opinion, already one crucial month has passed. Now, I’m not an economist, but I don’t think that even the federal government has the wherewithal to do such a recovery effort a second time. If it tried to do so, I believe, it would lead to hyper-inflation, a drastically lower stock market, and even violent social protest. Thus we have one opportunity to get this right before a much greater catastrophe engulfs us.

The bottom line is that to sustain America the way we know it, or knew it before March 1, Americans must get back to work, the quicker the better.

So then, how do we decide when that is, or even, who decides? Is it the president, Congress, state legislators, governors? Health officials, business owners? The people themselves? And what are the criteria?

One thing to me is clear. We can’t wait until everyone has been infected or until the last person with the infection has died. That would be months into the future. We must accept the risk, in fact the likelihood, that some persons will sicken and die after we resume working. That is certainly unfortunate, but the economic consequences of not resuming work are even more dire to our society.

Here are my suggestions, but they should be examined by statisticians and epidemiologists because these decisions are largely data driven:

First, employers must decide individually the risk to their enterprise, employees and customers from reopening. What are the COVID-19 trends in the community in which they operate? How well have they been able to function on line? How has the virus affected their market? (For example, if your business model depends on a large crowd of people gathering, it may take months for people to feel comfortable doing it.)

Second, how well have the local hospitals been handling those who need treatment? If they are overwhelmed, and people are dying from lack of care rather than from the virus itself, it’s hard to support a general reopening of business that runs the risk of increasing the number of patients.

Clearly one size does not fit all. It may be prudent to reopen business in Nebraska or Texas, for example, but not in New York or Los Angeles. Then again, if the infection rate is soaring in New Hampshire but the worst is over in New York, it might make sense to resume operations in New York but not New Hampshire.

When it comes to government oversight, our 50 governors have a better handle on local COVID-19 conditions than our national government. Working with the local businesses, I think that governors using their emergency public-health powers can individually decide when and who should reopen. This power could extend, as it does now, to in-state operations of large multi-state or international enterprises. Governors can give a go-ahead but it will be up to each business how to respond.

The federal government can provide resources and coordination. The president can use his bully pulpit to set the general direction ( as he has done by broaching the subject of return to work). What would help a lot is a computer model that considers for each enterprise the risks to itself and its customers and community of reopening its business. Certainly mathematicians and economists now have time and reason to build such models. Governors or private groups could then set markers for when resumption of business is prudent.

John H. (“Josh”) Fitzhugh is chairman of Montpelier, Vt.-based Union Mutual Insurance Co. as well as journalist and farmer. He was founding editor of the National Law Journal and was legal counsel to former Vermont Governors Howard Dean and Richard Snelling.

2d Amendment art

“Revolver 14’’, by Corey Pickett, in the group show “Either I Woke Up, or Come Back to This Earth,’’ at the Vermont College of Fine Arts, Montepelier.

The gallery says: “These artists use playfulness and humor to challenge histories of political violence and the anesthetic of nostalgia.’’

The Vermont State House, in Montpelier, the smallest state capital, which has only about 8,000 residents. It’s surprisingly arty and has a strong culinary scene, too. It hosts the New England Culinary Institute, which runs some local restaurants.

In downtown Montpelier

Montpelier in 1884

Macaulay in hip Montpelier

“Why the Chicken Crossed the Road,’’ by the famed David Macaulay, in the show “Macaulay in Montpelier: Selected Drawing and Sketches,’’ though Nov. 2 at the Spotlight Gallery at the Vermont Arts Council.

David Macaulay, now a Vermonter but previously a Rhode Islander, is a British-born illustrator and writer whose books have sold over 3 million copies in the United States and have been translated into a dozen languages. According to Macaulay, the featured works were "selected in the dark from hundreds of illustrations and at least five times as many sketches," representing "a tiny sliver of the vast amount of flotsam left in the wake of each book.’’

State Street, in downtown Montpelier.

Downtown shops, not surprisingly including yoga.

Montpelier in 1884. Note the domed state capitol.

Montpelier, in the Green Mountains, while the smallest state capital, is a remarkably hip city with good restaurants (Sarducci’s is terrific), galleries and other small-scale retailing. In the 19th and 20 centuries the city also had a good number of small manufacturers.

The city also hosts the the Vermont College of Fine Arts and the New England Culinary Institute, the latter helping to explain the presence of good restaurants. The main drawbacks are the long winters and the Winooski River, which, while scenic, from time to time floods part of the downtown.

Politics in a well-mannered micropolitis

Shops in downtown Montpelier.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb's Oct. 27 "Digital Diary,'' in GoLocal24.com

Politics in Rhode Island, where I live, can be pretty dispiriting because of excessive identity politics, some local corruption and a low level of intelligence, education and integrity and a high level of provincialism among too many politicians. (That’s partly due to local journalists and demagogic radio talk show hosts discouraging good people from running for office and very low voter turnout in primary elections.)

So I drove to Vermont last week to see a little bit of Norman Rockwell-style politicking.

The drive to and from Montpelier was a trip up and down memory lane. I headed west on Route 2 through northern Massachusetts’s by turns pretty and depressing villages and mill towns. The foliage was at its most colorful and the sky was azure. I took a slightly different route than usual, turning off Route 2 well before Greenfield and heading north through unexpectedly high and steep hills and deep countryside near Northfield before getting on Route 91, which runs north up the gorgeous Connecticut River Valley, through which I had driven so many times before.

The farther north I went, the less vivid the foliage; the North Country’s maximum color was about three weeks ago. But much of the landscape still glowed.

In Montpelier, I had dinner with two old friends, Josh Fitzhugh and his wife, Elizabeth. Josh is running as an anti-Trump Republican state Senate candidate for Washington County. We ate in an excellent restaurant called Sarducci’s in downtown Montpelier, which was crowded and cheery. Indeed, the city, although America’s smallest state capital, was surprisingly lively with lots of people on the sidewalks on a mild night.

After dinner we strolled to a small cable-TV studio, where Josh and some rivals had a “debate,’’ though it was really just a discussion, on such big local issues as preventing dirty water from entering Lake Champlain. Everyone was civil. The candidates had grown to know each other over the years in the intimate and generally friendly and honest atmosphere of the Green Mountain State.

Elizabeth (nicknamed “Wibs’’) and I sat in the waiting room outside the studio but we only heard a little of the “debate’’ on the big screen in front of the room because of technical problems. Sitting with us was a nice man called Jerome Lipani, like many Vermonters from New York City, who promoted some Bernie Sanders-style reforms to us.

Mr. Lipani, artist, was polite and good-humored and, I inferred, pragmatic, as was now-Senator Sanders, a socialist, when he was mayor of Burlington. Indeed, with a few exceptions, such as outgoing Gov. Peter Shumlin’s overreaching for a single-payer healthcare plan, pragmatism rules. Thus the same state will elect such moderate Republicans as the late Gov. Richard Snelling, such Democrats as former Gov. Howard Dean (who ran state government as a middle-of-the road fiscal conservative) and a professed (but realistic) socialist such as Bernie Sanders. Vermont candidates are judged by their records and characters far more than by their party labels. Given the increasing tendency in the U.S. to vote strictly by party and not by individual this was heartening.

Reliving again the state’s tradition of civility and civic-mindedness was a tonic, and I rather dreaded driving back to the nastiness of megalopolis. By the way, I discovered that Montpelier along with Barre, form something called a "micropolitan area'' and that tiny Barre and Montpelier are called the Twin Cities. Vermont cute!

xxx

An old book by Joseph Wood Krutch, The Twelve Seasons: A Perpetual Calendar for the Country, might help you get through the New England winter, especially in beautiful but, er, rigorous Vermont, New Hampshire and Maine. He sees each month as a season.

Indeed, every day is a season, emotionally speaking.