The rise of Pittsfield

Downtown Pittsfield, Mass., in 2014

Pittsfield has in the past few years come to be called the “Brooklyn of The Berkshires” because its gentrifying neighborhoods and innovative arts programs are to the Berkshires’ more upmarket towns, such as Lenox, as a certain outer borough is to Manhattan.

Don Pesci: An apolitical and literary jaunt in The Berkshires

A view of the Mt. Greylock Range from South Williamstown (from the west). The Hopper, a cirque, is centered below the summit.

—Photo by Ericshawwhite

Arrowhead, where Herman Melville wrote Moby Dick.

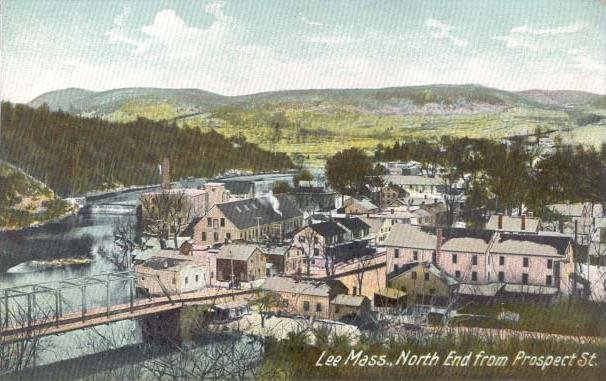

Lee, Mass., in The Berkshires, is everyone’s vision of a typical New England town. The Main Street is short and to the point. Buildings, unmolested by town planners, have maintained their character throughout the years. The house where we bunked for several days dates from the 19th Century and has been well kept by its owner, an engineer who had, like Odysseus, moved about in the world. He was born, very likely in or near the house we occupied, moved with his family to Washington, D.C., where his father had found a job that he could not refuse as an electrical engineer, and later back to Lee.

The firehouse across the street from Garfield House, where we stayed, is a solid stone structure that boasts a square steeple that one easily might mistake for a bell tower or a medieval watch tower.

Traveling around New England, one must – delicately, delicately – approach the topic of politics. Open wounds are everywhere. Much of New England is solid ultramarine blue (there are dramatic exceptions, such as Aroostook County, Maine). That is to say that many people in New England wish to see former Donald Trump in leg irons waltzing through a prison yard. My wife, Andrée, believes that such emotions are far too enthusiastic. She taught American Studies for many years and is intimately familiar with the religious enthusiasms of the 17th Century that saw a witch behind every bush.

Trump, she likes to say when not in the presence of people still suffering political whiplash from the 2016 Hillary Clinton/Donald Trump campaign, is, in some respects, a man more sinned against than sinning, though, of course, she would never say such things in the presence of those who wish to burn Trump at the stake – which is to say, in a good deal of New England. Consider that Democrats in Connecticut, a part of New England and our home state, outnumber Republicans by a two-to-one margin, with unaffiliateds topping Democrats by a small number.

Andrée laid down the law long ago: There will be no politics spoiling our vacations. This law of the household precedes Trump’s ascendency to the presidency by, say, a half century or more. No politics means no computers, no cell phones, no newspapers, no furtive notes written in the shadows, and only mercifully brief encounters with witch-burners.

“Just change the subject, will you?”

In very few places throughout the world -- Washington, D.C., of course, other uncivilized places that used to be part of the British Empire, including most of New England, and Italy— everywhere and always – political talk with strangers destroys the moment, and living in the moment is essential to travel. In Florence, Italy, we almost missed, through dreamy inattention, the spot where Savonarola had been burned at the stake. It is a grave sin to have eyes and not see, ears and not hear, when traveling about the world.

Just ask Odysseus, a victim of enchantment and forgetfulness during the year he spent, not unpleasantly, with Circe. First, the traveler forgets where he is, then who he is, and then the once-solid world dissolves like a dream.

“Pay attention!”

It was no chore for us to pay attention to Herman Melville, most famous, of course, as the author of Moby Dick. In college, he was our literary touchstone. One day, early in our marriage, I brought home a little-read book by Melville, Pierre or the Ambiguities. It’s a romance novel, and Andrée, an incurable romantic, fell for it head over heels. A little later, though we already had been married a couple of years, she fell for me, not quite head over heels.

We had visited Arrowhead, Melville’s home in Pittsfield, years earlier when the house was in transition. No one was home, the house, garnet-red at the time, was dark and forbidding and vacant. Even the spirit of the place had taken flight. We peeked in the windows. Off in the background, Mt. Greylock, the highest elevation in Massachusetts, showed his hump.

Melville wrote Moby Dick in this house. He dedicated the book to his good friend Nathaniel Hawthorne, then living part time in nearby Lenox. The book following Moby Dick, Pierre or the Ambiguities, was dedicated as follows: “'To Greylock's Most Excellent Majesty ... the majestic mountain, Greylock — my own more immediate sovereign lord and king — hath now, for innumerable ages, been the one grand dedicatee of the earliest rays of all the Berkshire mornings, I know not how his Imperial Purple Majesty ... will receive the dedication of my own poor solitary ray ...''

Greylock, we found, was full of winding ways, but so was Melville’s route through a tortuous world. Moby Dick, now considered a classic American novel, was a conspicuous failure in its day. And it was only after Melville had died that the book rose from its deadening reviews.

Today, as always, the book must be read aloud, not so much with the eye as with the ear of the heart. It is music to the ear and, like all music, it winds its way over long Shakespearian passages, moving gracefully at its own pace. It was this music that had enchanted Andrée so many years ago.

The trip to Arrowhead reminded me that traveling is an inward experience, not merely a collection of interesting photos taken of interesting places along the way.

Mark Twain, a Connecticut resident for many years, traveled widely in Europe. And partly on the basis of that, he wrote a little-read book he considered his best: “I like Joan of Arc best of all my books… It furnished me seven times the pleasure afforded me by any of the others; twelve years of preparation, and two years of writing. The others needed no preparation and got none.” (The full name of the novel is Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc.)

Twain was anti-clerical, not necessarily anti-religious. But the character of Joan, buried for many years under heaps of anti-Catholic perfidy, was paramount for Twain: “Taking into account…all the circumstances—her origin, youth, sex, illiteracy, early environment, and the obstructing conditions under which she exploited her high gifts and made her conquests in the field and before the courts that tried her for her life—she is easily and by far the most extraordinary person the human race has ever produced.”

The Mount, novelist Edith Wharton’s plush estate in Lenox, is only a 10-minute ride from Garfield House.

There’s a picture on one wall in the estate’s mansion of a salon gathering in which Henry James makes an appearance. Anything Jamesian is redemptive for Andrée. As an American Studies and American Literature teacher for many years, both in Catholic and public schools, she taught James and other famed authors to students who eventually came to appreciate James’s long winding prose paths – very Shakespearian and even Melvillean.

Twain was not a James fancier: “Once you put him down, you can’t pick him up again.”

But Andrée likes the winding ways of a strong – dare I say it? -- Faulknerian sentence, very much like the path the imagination takes when it is called into service in our travels.

Our next-door neighbor at Garfield House, a permanent resident and an expat from New York, told us that she had lived for a time in Wharton’s reading room while she was an administrator of the Shakespearian Company that put on plays at The Mount.

“You were an actress?”

“Oh, God no, please no – not an actress. I worked behind the scenes as an administrator to put on the plays.”

“In New York?”

“Yes. New York had become too cloying, so I came here, fell in love with the place and stayed. By the way, you told me that you like golf, but you do not like golfers. Just a word to the wise: You had better not say that to the proprietor of Garfield House, who is an avid golfer.”

I agreed, as Andrée said, to “change to subject” if it came round to golf.

Golf, like politics in New England, has become in recent days a secular religion full of saints and heretics – none of them, unfortunately, quite like St. Joan of Arc.

Twain on politics: “In religion and politics people’s beliefs and convictions are in almost every case gotten at second-hand, and without examination, from authorities who have not themselves examined the questions at issue but have taken them at second-hand from other non-examiners, whose opinions about them were not worth a brass farthing.”

Now there, Andrée might say, is a near perfect Jamseian sentence, very much like the hiker’s paths that cross and re-cross Mount Greylock. Our very last adventure before leaving Lee for home was to ride – not walk – to the top of Melville’s “sovereign lord and king.”

Don Pesci is a Vernon, Conn., based columnist.

Front Entrance of The Mount.

— Photo by Margaret Helminska

1907 postcard.

'Treacherously hidden'

“Arrowhead,’’ also known as the “Herman Melville House,’’ is a historic house museum in Pittsfield, Mass., in The Berkshires. Herman Melville (1819-91) wrote some of his major work there: the novels Moby-Dick (1851) Pierre (dedicated to nearby Mt. Greylock), The Confidence-Man, and Israel Potter; The Piazza Tales (a short story collection named for Arrowhead's porch); and magazine stories such as "I and My Chimney". Melville loved to gaze out his window at Mt. Greylock, at 3,489 feet the highest mountain in The Berkshires. Its shape reminded him of a whale.

“Consider the subtleness of the sea; how its most dreaded creatures glide underwater, unapparent for the most part, and treacherously hidden beneath the loveliest tints of azure….Consider all this; and then turn to this green, gentle, and most docile earth; consider them both, the sea and the land; and do you not find a strange analogy to something in yourself?’’

— From Moby-Dick

A view of the Mt. Greylock Range from South Williamstown (from the west). The Hopper, a glacial cirque, is centered below the summit.

‘Everything will come out now’

“Everything that’s been placed in him

will come out, now, the contents of a trunk

unpacked and lined up on a bunk in the underpine light.’

— From “The Summer-Camp Bus Pulls Away the Curb,’’ by Sharon Olds. She divides her time between Pittsfield, N.H., and York City,

The common in Pittsfield, in the south-central part of the Granite State

The Suncook River, in Pittsfield, in about 1908.

The town’s founder, John Cram, built gristmills and sawmills in Pittsfield in the late 18th Century, and since 1901, Globe Manufacturing has made protective clothing for firefighters there.

Don't depend on one company; mill village in verse

Cleanup activity at one of the General Electric Pittsfield plant Superfund sites on the Housatonic River, which the company heavily polluted in its heyday.

One thing that any community —in New England or elsewhere — should avoid is over-reliance on one or two big companies. Pittsfield, Mass., found that out when General Electric, which once employed 14,000 people at its facilities in that little city, closed most of its operations there, leaving economic devastation. Now, Pittsfield (the capital of the Berkshires) seeks a diverse collection of much smaller firms and is having modest success in turning around the city.

Jonathan Butler, the president and CEO of 1Berkshire, a business development group, told New England Public Radio:

“If we were to have another employer with 10,000 or 15,000 jobs come in, {to Pittsfield} that would scare me. I think that would scare those of us [who] work in economic development.”

I have strong memories of covering the 1970 elections in Pittsfield for the old Boston Herald Traveler. It then still had a thriving downtown, though you could sense slippage.

To read more, please hit this link.

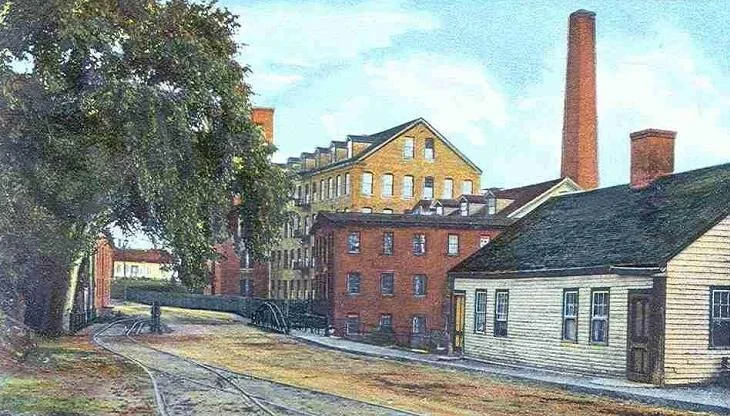

Assawaga Mill, Dayville, Conn., in 1909

Factory Town in Verse

Old New England mills (many of them beautiful, and built for the ages) and the towns that grew around them have become the subjects of a curious form of romance in recent years. So now we have poet, novelist, essayist, environmentalist and former Connecticut deputy environmental commissioner David K. Leff out with a verse novel, The Breach: Voices Haunting a New England Mill Town, which studies the decline of such a community facing economic and an environmental crises.

To hear Mr. Leff talk about his book, and read from it, please hit this link.

Returns of the day with coffee and doughnuts

"The Pundit'' (mixed-media encaustic), by NANCY WHITCOMB

I have many vivid memories of Election Days. First, there were those jolly little Eisenhower-for-President parades in '52 and '56 in the overwhelming Republican town I lived in. Then there was anxiously watching very late into the night the dubious election of 1960 as returns were dragged from (and invented in) Illinois and Texas to hand the victory to Kennedy. My mother, who was, well, crazy, was so angry about the outcome that she tried to throw the heavy new "portable'' TV on which she had watched the returns out the window but was restrained.

After Kennedy took office, my mother developed a weird romantic (erotic?) attachment to the Kennedys and was devastated about the murders of John and Robert -- events that my calm father responded to with remarkable, even eerie equanimity, even for him.

I remember Nixon's graciousness on TV about his defeat, though of course his resentments continued to simmer.

Then there was the dubious presidential election of 2000, with the Republicans taking that brass ring via Florida machinations and the U.S. Supremes, though it took weeks to be sure who officially "won''. To this day, who knows who really got more votes in Florida -- Gore or G.W. Bush? By that time I was too tired of politics to stay up most of the night watching the show, which I had done for decades, mostly because it was (sort of) part of my job.

But one election I remember with great pleasure. In November 1970 the old Boston Herald Traveler sent me to Pittsfield , Mass., to get the election returns from Berkshire County. It wasn't a presidential-election year but there was plenty of excitement about close New England races.

I had no idea how to go about getting the tallies in t. No one on in Boston gave me any guidance. "Bobby, just get them to us as soon as you can,'' was the directive from the city editor. In other words, be inventive. It was a test of my skills in the face of inexperience.

And not only did the paper urgently need the returns as soon as they were official but, even more urgently, the TV and radio stations they owned did. They were updating about every 15 minutes!

But I didn't have a clue. I first thought that maybe I should go to Pittsfield City Hall and some old Board of Canvassers guy could help me out. Or maybe the headquarters of Silvio Conte, the GOP congressman from western Massachusetts. As I wandered, increasingly anxious, down the streets of this mill town/county seat, (General Electric virtually owned it) on that wan November afternoon, I came across a radio station.

Maybe someone there could help me. This was before the huge radio-station chains took away most of the local sounds (including accents) you used to get on your local radio station, replacing them with national call-in blowhards, infomercials and other canned stuff. In the old days, most of the dominant small-city radio stations had at least one or two local news people and a news announcer with a nice baritone. (He might moonlight as the "Music in the Night'' announcer. Percy Faith and his Orchestra.)

I went into the station and sat down in the waiting room. Some middle-aged guy wearing a tattered tweed jacket came out and asked me what I wanted. "I have no idea what I'm doing. How do I collect all these votes?'' I said apologetically.

He asked me if I knew anyone around there. Well, yes, -- Frank Strom, an uncle of mine by marriage who had run the big local bank. (He later moved to Providence and did a fine job running the Old Stone Bank (RIP, both of them).

"A great man!,'' he said, noting that my uncle had provided ''half this town with mortgages.''

"We'll take care of you,'' he promised. Then a secretary brought me a doughnut and a cup of coffee and directed me to a phone in the corner. There I camped out for most of night as they brought me sheets of paper with returns scrawled in them (collected by one of the station's newsmen) to call in to the grumpy rewritemen in Boston. The station had "runners'' from all over that hilly county calling in votes.)

From time to time the station manager would relate some tales of local politicians, informed by cynicism and idealism, dislike and affection. I never quite figured out his political affiliation, if he had any.

The tough customers at the Herald Traveler were impressed with my speed and efficiency. I had a very pleasant drive back to the office the next day; the Massachusetts Turnpike had never looked lovelier. Of course I never told them how I got those golden returns.