Chris Powell: Abolish government pensions

New Haven Police Chief Otoniel Reyes is “retiring” at age 49 with a $117,000-a-year pension to move to nearby Quinnipiac University, where he’ll run the campus police at a salary that will probably be around $170,000.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Connecticut should prohibit pensions for state and municipal government employees, not because they are bad people or especially undeserving but for several solid policy reasons.

First, most of the taxpayers who pay for those pensions don't enjoy anything like them.

Second, state and municipal government can't be trusted to fund the pensions adequately.

And third, the pension system for state and municipal employees separates a huge and politically influential group from Social Security, the federal pension system on which nearly everyone else relies, and thus weakens political and financial support for it.

Connecticut state government has an estimated $60 billion in unfunded liabilities in its state-employee and municipal-teacher pension funds. But after attending the recent meeting of the state General Assembly's finance committee, Yankee Institute investigative reporter Marc Fitch wrote that another $900 million in unfunded liabilities are sitting in New Haven's pension funds.

According to Fitch, New Haven Mayor Justin Elicker testified about the city's pension-fund disaster, noting that city government faces a projected $66 million deficit in its next budget and that pension obligations are a major cause of it.

Of course the mayor attended the hearing to beg more money from state government for the city. Unfortunately no legislator seems to have asked Elicker about the $117,000 annual pension that the city is about to start paying its police chief, Otoniel Reyes, so that he can "retire" at age 49 to take a job with Quinnipiac University, in nearby Hamden, Conn., probably at a salary around $170,000, and begin earning credit toward a second luxurious pension. Indeed, no news organization in New Haven seems to have even reported the chief's premature pension yet.

Maybe legislators didn't ask about the "retiring" chief's pension because state government has been just as incompetent and corrupt with pensions as New Haven city government. These enormous and incapacitating unfunded liabilities are proof of political corruption and incompetence at both the state and city levels -- the promising of unaffordable benefits to a politically influential special interest.

Connecticut's tax system may be unfair, but it's not why New Haven is insolvent. Like state government, the city is insolvent because it has given too much away.

Government in Connecticut is good at clearing snow from the streets and highways because failure there is immediately visible. But beyond snowplowing government, in Connecticut is not much more than a pension and benefit society whose operation powerfully distracts from serving the public.

This distraction should be eliminated, phased out as soon as government recognizes that it has higher purposes than the contentment of its own employees.

xxx

Proposing his new state budget this month, Governor Lamont announced plans to close three of Connecticut's 14 prisons in response to the decline of nearly 50 percent in the state's prison population over the last decade.

A few days later New Haven's Board of Alders asked Assistant Police Chief Karl Jacobson to explain the recent explosion of violent crime in the city.

According to the New Haven Register, the assistant chief said there were 73 gang-related shootings in the city in 2020 against only 41 in 2019 and 32 in 2018. Murders in the city so far this year total seven, against none in the same period last year. So far this year there have been 12 shootings in the city, up from five at this time last year, and 36 shooting incidents this year compared to 20 at this time last year.

As usual, the assistant chief said, a big part of the violence in the city involves men recently released from prison who resume feuds and otherwise are prone to get into trouble. The police plan to hold preventive meetings with such men, and the city has just opened a "re-entry center" for new parolees.

The explosion of crime in New Haven, Hartford, Bridgeport and other cities does not sound like cause to close prisons. It sounds like cause to investigate prison releases and the failure of criminal rehabilitation.

Maybe the General Assembly would undertake such investigation if the former and likely future offenders were delivered to suburbs instead of cities. Then saving money by closing prisons might not be considered such a boast.

xxx

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester.

Chris Powell: New Haven police chief retires at 49 to pension bonanza; vaping vs. marijuana

Tony Reyes to go from the mean streets of New Haven to the relatively bucolic precincts of Hamden, Conn. Here we see Quinnipiac University’s Arnold Bernhard Library and clock tower, focus of main campus quadrangle.

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Everyone agrees that Tony Reyes has been a great police chief in New Haven, having been appointed in March 2019 after nearly two decades of rising through the ranks of the police department. But the city will lose him in a few weeks as he becomes police chief at Quinnipiac University next door, in Hamden. This is being called a retirement, but it is that only technically. In fact it is part of an old racket in Connecticut's government employee pension system, an abuse of taxpayers.

Typically police personnel qualify to collect full state government and municipal pensions after 20 years, no matter their age. Reyes is only 49, so he easily has another 15 years of working life ahead of him even as he collects a hefty pension from New Haven.

The chief's salary is $170,000 and so his city pension well may be half of that each year. After a week of requests City Hall was unable to provide an estimate of the pension, but then maybe city officials were too busy helping their Climate Emergency Mobilization Task Force figure out how to remove carbon from the atmosphere. In the meantime maybe the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency can handle New Haven's pensions.

Nor would Quinnipiac disclose what it will pay Reyes, though the university is a nonprofit institution of higher education whose tax exemption comes at the expense of federal, state and Hamden property taxpayers. But since a Quinnipiac vice president is paid nearly $600,000 a year, Reyes probably won't starve there.

In the absence of accountability from city government or the university, here's a guess: Reyes will draw an annual pension from New Haven of $80,000 a year while Quinnipiac pays him $150,000 a year. After 15 years at Quinnipiac, Reyes may get another annual pension of $80,000, plus $30,000 a year in ordinary Social Security, for total retirement income at age 65 of close to $200,000 annually -- as if half that wouldn't be lovely.

Pensions are ordinarily understood to be to support people whose working capacity is ended or substantially diminished. But pensions in state and municipal government in Connecticut often provide luxury lifestyles during second careers and after. Meanwhile mere private-sector workers are lucky to conclude their careers with enough Social Security and savings to scrape by on their way to the hereafter.

This scandal could be remedied easily, with enormous savings and greater retention of the best personnel. State and municipal legislation and contracts could restrict government pension eligibility to the customary retirement age of 65 or to the onset of disability before that. But that would require elected officials who had the wit to alert the public to how it is being exploited and the courage to stand up to the government employee unions.

It also would require news organizations to report the scandal in the first place. But it seems that not even New Haven's own news organizations have inquired about the police chief's pension bonanza.

xxx

The new session of the General Assembly will be intriguing for many reasons, maybe most of all for plans to legalize and tax marijuana while outlawing flavored "vaping" products and prohibiting the sale of tobacco products in stores within five miles of schools, which might limit tobacco sales to kiosks in the middle of a few state forests.

Both campaigns seem to be originating with liberal Democratic legislators. The House chairman of the Public Health Committee, Rep. Jonathan Steinberg, D.-Westport, an advocate of outlawing flavored vaping products, says, "There's plenty of documentation about how exposure to addictive products at a young age makes it hard for people to extricate themselves."

Of course, marijuana also can lead to addiction to other drugs. Some people deal with and outgrow dope smoking, but some don't.

Drug criminalization long has failed and probably has done more damage than illegal drugs themselves. But it is silly to pretend that outlawing "vaping" products will protect kids any more than outlawing marijuana has done.

Contraband laws just create black markets that make the law futile. If Connecticut opts for legal marijuana while prohibiting "vaping" products, it will be only because legislators believe that there's much more tax revenue in the former than the latter.

Chris Powell is a columnist for the Journal Inquirer, in Manchester, Conn.

Llewellyn King: Polls are setup shots and a plague for democracies

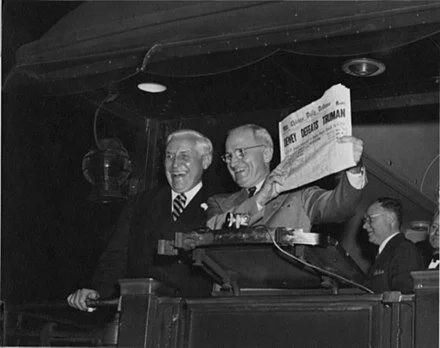

Nov. 3, 1948: President Harry S. Truman, shortly after being elected as president, smiles as he holds up a copy of the Chicago Daily Tribune issue prematurely announcing his electoral defeat. This image has become iconic about the consequences of bad polling data.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Damn, damn, damn the polls.

My irritation has nothing to do with how they botched this election, or how they botched the last two British elections or the Brexit vote.

It is not a matter, to my mind, of whether the polls get it wrong. It is a matter simply that they are taken at all. I have been railing against them for years.

I have found pollsters on the whole – I have interviewed quite a few -- to be decent, honest people who believe that they are taking the voters’ temperature scientifically; that their work is helpful, contributing to the national or regional understanding.

But polls are far from the benign things they purport to be. They are a setup shot that becomes the movie; a snapshot that changes the course of events, a contrived intrusion into the public discourse that then monopolizes it.

Polls sideline good people, bring into favor the known over the unknown, and promote a kind of national continuation. They begin to write the narrative, not to reveal it. They terrify timid leaders and office aspirants.

These same arguments can be made against a lot of market research. Ask people what they like, and they will tell you they like what they know.

Imagine if Harold Ross, the genius who was founding editor of The New Yorker magazine, had polled the public about the magazine he was about to start in 1925, and had asked, “Do you want a magazine in which the articles are long, the bylines are at the end of the articles, the headlines are in squiggly type, and there is no table of contents?” Do you think that there would be The New Yorker (it still has long articles, but the bylines are at the beginning, and it has a table of contents) today?

The most blame in the plague of polls that now distorts our elections belongs with the news media.

They commission polls relentlessly and then publicize the results, as though they have been allowed to see the face of God. This synthetic news.

Polls are not the revealed truth. They are an imperfect peek into the national thought portfolio. But once they become part of that portfolio, they corrupt the momentum of events.

Worse, polls sway the politicians. They turn the Pied Piper into one of the rats, getting in line with the rest.

In his Sept. 30, 1941 review of the war to the House of Commons, Prime Minister Winston Churchill chose to address the subject of opinion and leadership. He said, “Nothing is more dangerous in wartime than to live in the temperamental atmosphere of a Gallup Poll, always feeling one’s pulse and taking one’s temperature. I see that a speaker at the weekend said that this was a time when leaders should keep their ears to the ground. All I can say is that the British nation will find it very hard to look up to leaders who are detected in that somewhat ungainly posture.”

Quite right.

The damage is that polls have proliferated in recent years, and they perform various functions for various people. Universities and colleges have found, as in the case of the Quinnipiac University Poll, that polls are a branding asset. The Quinnipiac poll is run by a small college in the rolling hills of Hamden, Conn., with great professionalism and objectivity, which has given it considerable standing in the world of polling. It also has enhanced the standing of the college which runs it.

My quarrel with the polls will be partly assuaged if they continue to get it wrong. That way they will take their place in the background clutter, not the breathtaking political snapshots that undermine elections.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C

Web site: whchronicle.com

John L. Lahey: Make curricula faster, cheaper and better

Quinnipiac University’s Arnold Bernhard Library and clock tower, the focus of main campus quadrangle, in Hamden, Conn. Sleeping Giant Mountain is in the background. The author of this essay is a former president of the university.

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

During my 40-plus years working in higher education I have witnessed a remarkable transformation in a wide range of industries – telecommunications, computing, transportation, media, publishing, manufacturing and retailing, to name a few. In almost every case these transformations have resulted in an improved product and/or service that is more responsive to consumer needs, more efficient and effectively produced, and offered at lower and lower cost to the consumer. The most obvious exception to all of these industry transformations is higher education.

Every year for the past 10 years I’ve made it a point to attend a futuristic conference in Silicon Valley having nothing to do with higher education. I was more interested in learning how high-tech Silicon Valley entrepreneurs viewed the world and the culture that attracted and produced these innovators and their startup companies. I was truly amazed at the extent to which these Silicon Valley entrepreneurs believed they were just one algorithm away from radically changing a long-established industry, its product or services, or creating an entirely new one. The mantra for these entrepreneurs and Silicon Valley generally is: faster, cheaper, better.

Using these same standards of faster, cheaper, better, let’s apply them to higher education and the changes that it has witnessed over my 50-plus years dating back to 1964. For starters: The bachelor’s degree that I earned in 1968 took me 120 credit hours, eight semesters, and four years to achieve. The per-credit-hour charge back then was $21. That same degree today costs about $1,200 per credit (both based on private university tuition costs). With respect to “better,” I’m willing to accept that today’s undergraduate education is at least as good as it was when I was a student, although frankly I’m hard-pressed to say that it is significantly better. And with respect to “faster,” the same bachelor’s degree that I earned in 1968 still today takes 120 credit hours, eight semesters, and four years to complete.

In short, the degrees that higher education awards today versus 50 years ago are neither faster nor better and certainly not cheaper. Earning a degree today costs about 57 times more than what it did five decades ago. All of which leads me to an opportunity for efficiency which has largely been overlooked in higher education, namely the curriculum. And the beauty of this opportunity is that it offers the best if not the only hope for higher education to satisfy all three of the Silicon Valley goals of faster, cheaper and better.

Seven years ago, at my urging, Quinnipiac University developed a number of accelerated dual-degree bachelor’s/master’s programs (originally called 3-plus-1 programs). The first one we developed was a bachelor’s in business combined with an MBA. The second was a bachelor’s in communications combined with a master’s degree in communications/journalism. These two combined offerings already existed at Quinnipiac as separate degree programs that required five years or 10 semesters to complete at the cost of five years or 10 semesters of tuition.

Our newly developed accelerated dual-degree programs offered these same two degrees in four years or eight semesters at a cost of four years or eight semesters of tuition. This accelerated program reduced by one full year both the time of completion and the cost of tuition yielding a savings or cost reduction of 20% or approximately $40,000. In addition, shortening the time of completion by one year allowed the graduates of these programs to enter the workforce one year earlier, offsetting the cost even further depending on the salary earned that first year after graduation. For example, a net income from a first-year take-home salary of $60,000 combined with $40,000 in reduced tuition effectively reduces the cost of dual degrees by 50% from $200,000 for the traditional five years of tuition to $100,000 with four years of tuition payments of $160,000 reduced to $100,000 by earning $60,000 net income in the fifth year.

These accelerated dual-degree programs have been expanded to other schools and colleges at Quinnipiac and now include additional 3-plus-1 programs, as well as 3-plus-2 programs and 3-plus-3 programs for dual degrees that traditionally required six or seven years to complete at a cost of six or seven years of tuition.

The common thread for all of these dual-degree programs is that they shorten the traditional amount of time required by one year, reduce the cost of the dual degrees by one year’s tuition and allow the graduate to enter the workforce one year earlier, earning an extra year’s salary. The popularity of these programs has grown such that over 20% of the Quinnipiac freshmen entering in the fall of 2018 were enrolled in one of these dual-degree programs.

The key element in the success of these programs both academically and financially is the curriculum and specifically the elimination of duplication within the curriculum for a bachelor’s and a master’s in the same program, such as business or communication. Most people believe the cost of higher education has gone up dramatically in large part because we are a personnel intensive industry. But I submit that the reason we need so many faculty and other personnel is because the curriculum has expanded and expanded over the years with little effort to eliminate unnecessary duplication of content among many bachelor’s degrees and their corresponding graduate degrees.

To end on a positive note: If we do indeed expand our focus on the curricula and eliminate unnecessary duplication within degree programs, we will not only lower the cost of higher education, but unlike with traditional cost reduction efforts, we will not compromise quality. Reasonable class sizes and full-time faculty-to-student ratios can be maintained for optimal learning. At the same time, more efficient curricula will more effectively engage and challenge today’s students who are far ahead of educators in their desire for all things faster, cheaper, better.

John L. Lahey is president emeritus and professor of logic and philosophy at Quinnipiac University, in Hamden and North Haven, Conn.. He served as president from 1987 to 2018.