The erosion of the college 'bookstore'

The Harvard /MIT Coop's (aka Harvard Cooperative Society) main store on Harvard Square was built in 1924 and designed by Perry, Shaw & Hepburn in the Colonial Revival style.

—Photo by Beyond My Ken

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

It’s sad to see how college bookstores, once major and charming attractions in New England’s many college towns, are being ruined by the chains that have bought them. There are fewer and fewer books as they’re replaced by the likes of logoed sweatshirts, tacky tchotchkes and other junk.

The Brown “Bookstore’’ is particularly depressing. If you want to go to a real bookstore in Providence, I recommend Symposium Books, downtown, or Books on the Square and Paper Nautilus, on Wayland Square.

I guess that the Internet, by taking away the monopoly on textbook sales, helped drive a stake through the old college-bookstore business model. Even the once grand Harvard/MIT Coop bookstore is a skeleton of its former self.

Reading on a screen is not the same as reading on paper, which is easier on the eyes and better supports comprehension and memory of the material. I thought of this the other day in the Route 128 Amtrak/MBTA station, where there’s no longer a newsstand. For that matter, other than one helpful and lonely Amtrak clerk there are no longer any service people to buy tickets or coffee from, or ask a train-schedule question. Heading to the paperless and, for some, serviceless society.

Emerson College occupies this row of buildings across from the corner of Boston Common

— Photo by John Phelan

Even in the pouring rain in downtown Boston last Tuesday, it was fun to see a dozen Emerson College film students shooting scenes on the sidewalk across from the Common. Most appeared to be of East Asian ancestry and half of them had haired dyed green, purple or blue.

Those old small-town reports

The Cohasset Common still looks much as it did in the ‘50s except the elms are gone because of Dutch Elm Disease.

Still the venue of generally polite town meetings

— Photo by ToddC4176

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

The other day I looked at municipal reports of my hometown, Cohasset, Mass., in the late ‘50s, when I lived there. There have been big changes since then, among them that Republicans outnumbered Democrats by more than 5 to 1, reflecting the old allegiances of small-town New England Yankees back then: The town’s Democratic now. And they called the town dump the “town dump’’ instead of the euphemism of Cohasset’s current “Recycling Transfer Station’’.

The old reports’ language was a bit more formal than now, indeed sort of Victorian, to wit, in the late ‘50s: “That the Selectmen are instructed to advise His Excellency the Governor and our Senators and Representatives….” And nicknames are frequently used now in the reports, a practice unheard of back then.

There were also such reminders of the passage of time as Memorial Day being called Decoration Day (in my house we still called Veterans Day Armistice Day back then) and a plan to spray a wetland with DDT, the environmental menace that wouldn’t be banned until 1972. But perhaps the most noticeable change was that most of the names of town officers in the reports in the late ‘50s were WASP, and now there are lots of Irish and Italian names, and some names whose ethnicity is hard to figure. Those once-city dwellers left the city to move to the suburbs, including now-rich ones such as Cohasset.

But I was charmed to read that the town still has that old colonial occupation of “fence viewers,’’ charged with dealing with property disputes.

You can learn a bit of local culture and sociology by reading old small-town reports.

The ecological empires of oaks, Charter and otherwise

Large white oak

Adapted From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

That Southern New England has so many kinds of trees helps explain much of its ecological richness. Oaks are among the most common. I always thought of them as rather boring, especially because their leaves turn blandly brown in the fall and tend to hang on until spring. (I do have fond memories from childhood of tree houses in them and acorn fights.) But Douglas W. Tallamy, an entomologist at the University of Delaware, talks up oaks in his new book, The Nature of Oaks: The Rich Ecology of Our Most Essential Native Trees.

Mr. Tallamy explains how oaks support more life-forms than any other North American tree genus. They provide food (especially acorns and caterpillars) and protection for birds, mammals (consider squirrels, racoons, bears and bats), insects and spiders, as well as enriching soil, holding rainwater and cleaning the air. And they can live for hundreds of years.

“There is much going on in your yard that would not be going on if you did not have one or more oak trees gracing your piece of planet earth,” he writes in the book, which shows us what’s happening within, on, under, and around these trees.

Mr. Tallamy offers advice about how to plant and care for oaks, and information about the best oak species for your area.

Hug your oak trees and/or plant some. (And if they get uprooted in a storm, they make about the best firewood.) Fewer lawns, more oak trees, please. Now that it’s April, those remaining ugly brown leaves from last year will soon be pushed out and we’ll soon be enjoying the shade under oaks’ expansive canopies.

“The Charter Oak” (oil on canvas), by Charles De Wolf Brownell, 1857. It’s at the Wadsworth Atheneum, in Hartford.

The Charter Oak was an unusually large white oak tree in Hartford. It grew from the 12th or 13th century until it fell during a storm in 1856. According to tradition, Connecticut's Royal Charter of 1662 was hidden within the hollow of the tree to thwart its confiscation by the English governor-general. The oak became a symbol of American independence and is commemorated on the Connecticut State Quarter.

Photos of acorns by David Hill

Philip K. Howard: Public-employee unions have been a disaster for democracy and the public interest

The NEA is the largest union in the United States.

It’s time to rethink the role of public-employee unions in democratic governance.

Public-union intransigence has contributed to two of the most socially destructive events in the COVID-19 era. Rebuilding the economy after the pandemic ends also will be more difficult if state and local governments have to abide by featherbedding and other artificial union mandates.

Public-employee unions are politically impregnable, but their corrosion of first principles of democratic governance may leave them open to constitutional attack.

The lack of accountability imposed by union contracts has corroded democratic trust. The nearly nine-minute suffocation of George Floyd by Minneapolis policeman Derek Chauvin, every second shown on video, touched off protests around the country and social anger that may impact race relations for years.

But Chauvin should not have been on the job, and he likely would have been terminated or taken off the streets if police supervisors in Minneapolis had had the authority to make judgments about unsuitable officers. Chauvin had 18 complaints filed against him and a reputation for being “tightly wound,” not a good trait for someone carrying a loaded gun.

But police union contracts make it very difficult to terminate officers. Out of 2,600 complaints against police in Minneapolis since 2012, only 12 resulted in any sort of discipline and no officers were terminated. A 2017 report on police abuse nationwide revealed that union contracts make it extremely difficult to remove officers with a repeated history of abuse.

Teachers unions wield similar power. Dismissing a teacher, as one school superintendent told me, is not a process, it’s a career. California ranks near the bottom in school quality but is able to dismiss only two out of 300,000 teachers in a typical year.

Because of COVID-19, teachers unions have adamantly refused to allow teachers to return to work for a year, harming millions of students.

Because many parents can’t work if children are not in school, teachers unions are also impeding our ability to reopen the economy.

Yet most parochial and private schools in the U.S. have reopened, without serious consequences, as have schools in Europe. It is safe to reopen schools, according to the Centers for Disease Control, as long as teachers and students follow certain protocols. Unions now say they’ll put a toe in the water, starting in the spring, when another school year is almost over.

The bottom line is inescapable: Public-employee unions do not serve the public's best interests.

How did public-employee unions turn into public enemies? Until the 1960s, collective bargaining was not lawful in government — it’s hardly in the public interest to give public employees power to negotiate against the public interest.

As President Franklin Roosevelt put it: “The process of collective bargaining… cannot be transplanted into the public service…. To prevent or obstruct the operations of Government …. by those who have sworn to support it, is unthinkable and intolerable.”

Public-employee union power is largely an accident of history, one of the many unintended effects of the 1960s rights revolution. The first shoe to drop was Executive Order 10988, in which President John F. Kennedy, as payback for political support, permitted collective bargaining for federal employees.

Public unions soon demanded similar rights from states. Without any serious debate, New York in 1967 permitted collective bargaining, followed by California in 1968.

Unions gained strength with every new administration. The rhetoric was virtuous: Who can be against the rights of public employees? But the velvet glove of rights barely disguised the political iron fist.

Public employees represent almost 15 percent of the work force, probably the largest organized voting bloc. For more than 50 years, generations of political leaders have promised whatever it would take to get their support, including shields against accountability and rich pensions and benefits. In Illinois, a state now actuarily insolvent, 20,000 public employees enjoy pensions of more than $100,000 per year.

A political solution is almost impossible. Union contracts have long tails, tying the hands of successive political leaders. Their political power also is different from that held by other interest groups; political leaders are powerless without their cooperation.

As labor leader Victor Gotbaum once put it, “We have the ability, in a sense, to elect our own boss.”

Public unions wield this power not just to get benefits, but to dictate how government works. After 80 meetings trying to cajole teachers back to work, Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot concluded that “they’d like to take over not only Chicago Public Schools, but take over running the city government.”

Democracy can’t work if elected officials lack the ability to run government. As James Madison put it, democracy requires an unbroken “chain of dependence… the lowest officers, the middle grade, and the highest, will depend, as they ought, on the President.” By shackling political leaders with thick contracts, and eviscerating accountability for cops and teachers, public unions have removed a keystone of democratic governance.

Public unions are not a problem anticipated by the framers of the Constitution. But Article IV, Section 4 of the Constitution provides that “the United States shall guarantee to every State in this Union a Republican Form of Government.” Known as “the Guarantee clause,” the provision has never been asserted in this context.

The history of the clause suggests that, by guaranteeing “a republican form of government,” the framers meant to ensure that government would be accountable to voters and not to a monarch or other unaccountable power.

Public unions have severed a key link between voters and governance. They are immune from accountability, collect tribute in the form of featherbedding work rules and excessive pensions, and control what they do day-to-day instead of what voters need.

It is time for a reckoning. The abuses of rogue police, teachers who won’t teach, and other indefensible public union controls cry out for constitutional redress.

Philip K. Howard, a New York-based lawyer, author, civic and cultural leader and photographer, is founder of Campaign for Common Good and chairman of Common Good (commongood.org), a nonprofit legal- and regulatory-reform organization.

His latest book is Try Common Sense: Replacing the Failed Ideologies of Right and Left.

This column first ran in USA Today.

Full disclosure: The editor of New England Diary, Robert Whitcomb, has collaborated with his friend Mr. Howard in some Common Good projects.

Port Authority Police Benevolent Association, Englewood Cliffs, N.J., a typical small-town police union.

Subsidize your strengths

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

With all the government goodies used to lure big companies, it’s refreshing to see a little state government help for small local companies that have a comparative advantage. That advantage can stem from their location, in Rhode Island’s case being on the ocean.

I write here of two companies.

One is Quonset-based American Mussel Harvesters, an aquaculture company that raises mussels, oysters and clams in the Ocean State. Shellfish aquaculture has been hard hit by the pandemic because the products have been primarily sold to restaurants. But the Rhode Island Commerce Corporation decided on Jan. 29 to give the company a $50,000 grant to help design a new bagging system for two-pound bags to sell to individual customers. Restaurants have generally been buying 10-pound bags. Much of the restaurant sector will come back, albeit in different forms, when COVID fades, but certainly shellfish farmers need to diversify their customer base a lot.

Meanwhile, the Commerce Corporation is making a $49,972 grant also appropriate to the Ocean State: Helping Flux Marine, of East Greenwich, in a project to make electric outboard motors. There’s the green-energy aspect, of course, but there’s also that there wouldn’t be gasoline spills from these outboards.

Beats putting money into the local casino business, including its support system (e.g., IGT, the gambling-tech giant and partners with its pending 20-year, no-bid Rhode Island state contract). Casinos prey on lower-income people and send much of their money out of the region.

Get it over with

Rocky Marciano (second from left) with Boston Mayor John F. Collins (center-right) and comedian and singer Jimmy Durante (right and famous for his impressive nose), circa 1968. The man at left is unidentified.

“Why waltz with a guy for 10 rounds if you can knock him out in one?’’

— Rocky Marciano (birth name) (1923-1969), an American professional boxer who competed from 1947 to 1955, and held the world heavyweight title from 1952 to 1956. He is the only heavyweight champion to have finished his career undefeated. He was born and brought up in the shoe-making city of Brockton, Mass. Her died in a plane crash in 1969.

A shoe factory back when Brockton called itself “The Shoe Capital of the World.’’ My paternal grandfather was a manager in the George E. Keith Co., which made Walk Over shoes, which were considered high end. Brockton went into steep decline with the departure of most of New England’s shoe industry for the South and abroad. But the city has enjoyed a bit of a revival in recent years, as some entrepreneurial energy from very rich Greater Boston has spilled into the old mill town.

— Robert Whitcomb

Distraction via exploration

“Scituate Beach, Massachusetts,’’ byThomas Doughty, 1837

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

When things in the world in general and/or in your own little world in particular seem almost intolerably tense, you can’t beat wandering around in nature without an itinerary for relief. I remember that fondly from my boyhood in a small, still partly rural, town on Massachusetts Bay. Alone, or with a pal or two, I’d go “exploring’’. And it was a good place to explore.

There were beaches, more pebbles than sand, with rocky headlands and innumerable sea birds, some of which would attack if you approached their nests. There were shark’s eggs to pick up, along with lovely sea glass (this was before the explosion of plastic pollution), and horseshoe crab shells amidst the seaweed dumped on the beach at the high-tide mark. (There were also tin cans to shoot at with BB guns.)

After northeast storms, we’d look for small boats that might have been tossed ashore.

Nearby were bullrush forests along the marshes, through which we’d make trails leading to little “rooms” we’d create. We’d use rowboats to explore the tidal rivers through the marshes, with their often sulfurous smells.

Sometimes in midwinter the more brackish and less salty marsh streams would freeze up and we’d do our exploring on skates.

Inland, small streams beckoned us to find their sources, and we’d check out a nearby farm, fragrant in certain weather with the aroma of manure, where we would sometimes intentionally irritate the bulls. There were rock-topped mini-mountains and tall oak trees to climb and abandoned houses to trespass in. (See poem fragment above.) And everywhere pleasing smells, such as of cedar trees, of which we had a lot, and flowering trees in May, of wet, newly cut grass and of rotting apples on the ground in the fall.

And the sights, smells and sounds could vary much from day to day, with the sharpest changes in early spring. Every day’s light was different.

What a miraculous world!

— Photo by Stefan-Xp

While this winter has generally been milder than usual, it looks like we won’t be getting the “January Thaw” – that sweet stretch of days with temps in the 50s that we often get at this time of year in New England, giving us a tempting taste of spring. A January Thaw would have been particularly appreciated by COVID-desperate restaurant owners because they could more comfortably serve customers outdoors.

Meanwhile, while most (?) New Englanders like mild winters, that our winters are getting warmer and shorter is a bad sign for the world, showing that man-fueled global warming is speeding up.

Is Watch Hill in Rhode Island?

Watch Hill Harbor

A colleague in a business ZOOM meeting I was in last Friday suggested that Rhode Island Gov. and former venture capitalist Gina Raimondo will not return to Rhode Island after she serves as Joe Biden’s commerce secretary. — that she’ll join the swells and move to some fancy out-of-state place.

No, I suggested, only half-jokingly, she’ll move to hyper-rich Watch Hill. Then another colleague quipped: “Is that in Rhode Island?” I had had a sleepless night and so too quickly and stupidly answered what everyone in the meeting well knew: “Watch Hill is in Rhode Island; it’s part of Westerly.’’

But in a psycho-sociological way, it’s not in Rhode Island. Like some other fancy places in New England — say Nantucket, Mass., and Northeast Harbor, Maine, it transcends its state; above all, it’s part of the Federated Principalities of the Plutocracy.

— Robert Whitcomb

Yachts in Nantucket

In Northeast Harbor. See mansions on the hillside.

— Photo by Billy Hathorn

Economy looking wetter in Rhode Island

The tiny, five-turbine wind farm off Block Island. It’s still the only offshore wind farm in the U.S. even as there are huge offshore wind farms in Europe.

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

It’s always good to see the Ocean State taking more advantage of, well, the ocean. There are two developments worthy of note. One is Gov. Gina Raimondo’s plan, working with National Grid, for Rhode Island to get 600 more megawatts of offshore wind power, as part of her hope to get all of Rhode Island’s electricity from renewable sources by 2030. That’s probably unrealistic but a worthy goal nonetheless. Certainly it would be a boon for the state’s economy to have that regionally generated power. Ultimately, with the development of new advanced batteries to store electricity, it would lower our power costs while making our electricity more reliable, helping to clean the air, slowing global warming and providing many well-paying jobs.

There is, however, the danger that if the Trump regime stays in power, it will slow or even sabotage offshore-wind development because it’s in bed with the fossil-fuel sector.

Then there’s the happy news that the Rhode Island Commerce Corporation plans to buy more land for the Port of Providence. This would come from a $70 million port-improvement bond issue that voters approved in 2016. $20 million of that is for expanding the Port of Providence. Considering its geography and location, Rhode Island for more than a century has used far too little of its potential to host major ports, with of course Providence and Quonset being the main sites.

Observers see considerable synergies between those ports and big offshore-wind operations off southeastern New England, much of which could be served from Rhode Island, as well as from New Bedford.

Please hit these links to learn more:

https://www.utilitydive.com/news/national-grid-to-develop-600-mw-offshore-wind-rfp-for-rhode-island/587866/

https://www.usnews.com/news/best-states/rhode-island/articles/2020-10-27/after-4-years-state-moves-to-buy-land-near-providence-port

Open summer, squeezed summer

— Photo by Dietmar Rabich

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

We seem to remember the arc of summers much more than those of winters. I remember many individual summers with vividness; they were all so different. But I recall the summer of 1970 with particular sharpness. I had just graduated from college and, trying to decide whether I really wanted to go to graduate school, decided to take the summer off, helped by a few bucks I had saved up. I had had summer jobs since I was 14.

It was still in many ways the phenomenon called “The Sixties,’’ with sex, drugs and rock and roll, etc. Wide open. While I was mostly living in Greater Boston that summer, I spent a lot of time driving around the Northeast alone or with my girlfriend of the time seeing friends, hiking, fishing, going to parties, etc. It was my last extended stretch of free time up until, well, now. I had a VW Bug and felt pretty close to fancy free, jumping into the car at a moment’s notice for a road trip to the mountains, the Maine Coast or New York City, often driving off in the middle of the night.

I would have felt more guilty about “wasting time” like this except for some advice my father gave me around that time, which was to take some time off before truly adult duties came rushing it. He had done the same thing in the summer of 1939, right after his college graduation and after having had all-day summer jobs since his early teens; in having these jobs, he was lucky – it was, after, the Great Depression. That fall he went off to work for an industrial company, then came “The War’’ (as we always called it), marriage and five kids. He had few breaks until he died of a heart attack, in 1975.

In any event, I decided not to go to grad school that fall and instead went to work, in a business – a Boston newspaper -- with long and unpredictable hours. Grab the free time if you can.

A cool day in late August, breaking a heat wave, is enough to get you thinking of the brevity of summer and indeed of life.

A Squeezed Summer

Mobility is often associated with America, whether in pursuit of money or pleasure. So perhaps what many of us will most remember from this summer is its COVID-caused lack, what with states imposing draconian quarantine rules, transportation service cutbacks, and many places you’d otherwise visit closed for the duration, or forever. It’s been a tough summer to gain that brief sense of release that summer vacations well away from home bring. Lucky people at least have leafy neighborhoods to stroll in, preferably with water to look at

If a vaccine really does come along, the anti-vaxxers don’t ruin everything and the economy improves, will there be a surge of travel next year, or will a newly aroused fear of disease scare people away from travel, especially long-distance, for years, however strong their urge to get away?

Dress rehearsal for big one

Tree and car whomped by Isaias in Waterford, Conn.

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

After that surprisingly lively outer band of Tropical Storm Isaias’s rain and wind swept through Rhode Island last Tuesday, I went for a walk when it was still breezy. It was exhilarating. The storm had cleaned out the oppressive air and the world seemed briefly fresh and new again. People I passed on the street seemed in good spirits.

But the very brief event also warned of how much damage a full hurricane could do in our densely treed region. If 60-mile-an-hour gusts could take down so many branches and even some trees last Tuesday imagine what 100-mile-an-hour winds could do to our electricity system, roofs and cars parked under trees. (A tree crushed a car up the street from us Tuesday.) Actually, I don’t have to imagine much, having strong memories of what Hurricane Bob did just east of Providence in ’91, not to mention such earlier hurricanes as Donna, in ’60, and, as a little kid, Carol in ’54.=

Perhaps National Grid has learned a few new lessons from Isaias in getting ready for a real storm and its aftermath. Especially with sea-surface temperatures so high just south of New England acting as fuel if a hurricane heads this way, that tempest may come sooner rather than later. Stock up on Sterno!

xxx

‘New Englanders tend to be a bit wary, and so they don’t particularly exert themselves to meet new neighbors. Indeed, you might never meet people who have lived across the street from you for years. But I’ve noticed, on our block anyway, newcomers and long-established neighbors chatting away – about six feet apart -- much more these days as folks stroll to relieve claustrophobia and get mild exercise. Paradoxically, COVID-19 may be making neighbors friendlier.

“Funny how we’re all talking to each other now,’’ one lady down the street told me as I was walking our dog.

A WPA for transportation?

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Traffic is starting to back up again in southern New England roads as the economy opens up in fits and starts. I found it bumper to bumper for a while the other week on Route 128 west of Boston. The roads are crumbling and the environmental effects of our extreme car-dependence are obvious. We need to expand mass transit. Yes, fear of COVID-19 has taken a toll on transit ridership but the frustrations and dangers of car travel (far more dangerous than travel on trains and buses) will soon enough send many people back to the likes of the MBTA.

Meanwhile, gasoline prices are very low and will likely continue so for some time to come. So when this depression ends, gasoline taxes should be raised to make the long-delayed improvements in transportation that will be good for the environment and for the economy. Maybe some people left permanently jobless by the pandemic depression can be employed in (Great Depression-era) WPA-style work to help fix the region’s worst transportation problems.

A WPA road project, in the Great Depression

Explosive evenings

M-80

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Residents of Providence are being increasingly disturbed by fireworks and firecrackers being set off for hours every night, especially in poorer neighborhoods. Lots of these are being illegally used, since in Rhode Island only ground fireworks and sparklers can be legally ignited – in other words, quiet displays -- with firecrackers, rockets and mortars or other devices that launch projectiles banned, except, I assume, for professionally run public fireworks displays that we used to enjoy on special occasions, especially The Fourth and New Year’s Eve.

The racket, injuries and fire threat from illegally used fireworks is one of those quality-of-life issues, like graffiti, that can drive people away from a city. The police must crack down hard. And the explosives are hurting the sleep we need, especially in these tenser-than-usual times. If some folks see the fireworks as an expression of personal or political liberation many more see them as reminders of entrapment in an urban dystopia.

Knock it off.

Ah, if only people were as interested in reading the Declaration of Independence as in making a lot of noise.

The fireworks frenzy is happening in other cities, too. Please hit this link.

The year-round fireworks dilutes the excitement that we used to feel as we approached the public celebrations of the Glorious Fourth of July, which I suppose won’t happen this year in most places. When I was a kid we lived on the coast and so most of the fireworks spectacles we enjoyed were on beaches. But we also, probably illegally, had our private shows, mostly involving devices such as M-80s, cherry bombs and Roman candles, in backyards – with the nearby thick woods muffling the noise a bit. But that was only on the Fourth, when the local cops, who seemed to know everyone in town, would look the other way.

My father would stock up several years worth of fireworks in Southern states, where laws were lax. (Now the laws are very lax in New Hampshire — Live Free and Blow Off Your Hand.

Then there was the little cannon he set off every year on the Fourth. We had a loud old time for several hours.

A few boys would light and throw M-80s and cherry bombs at each other (but only on The Fourth!), displaying the same sort of idiocy as in the BB-gun wars they had through the year, in which it was possible to lose an eye or two. Cheap thrills indeed!

Health-care behemoth coming for a tiny state?

Behemoth as depicted in the Dictionnaire Infernal

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Good out of bad? Lifespan and Care New England, Rhode Island’s two big “nonprofit’’ hospital systems, have had to tightly coordinate their responses to the COVID-19 crisis – an experience that has led them to revive merger or at least “collaboration’’ plans. A merger might save on administrative and other costs borne by the public and enable the state to have a system big and strong enough to compete with the Boston health-care behemoth by maintaining a full-range of medical services and research in the Ocean State and by strengthening its only schools of medicine and public health, at Brown University. A merger might preserve a lot of jobs in Rhode Island. But at the same time, many jobs would presumably be lost as the merged company eliminated redundancies.

Of course, such a large and powerful merged entity would have to be carefully regulated. As Michael Fine, M.D., warned last week in GoLocal, such mergers have tended to raise health-care consumers’ costs because of the monopoly pricing-power created. And I wonder what gigantic golden parachutes, paid for indirectly by the public, would go to Lifespan and Care New England senior executives in a merger.

To read Dr. Fine’s comments, please hit this link.

Wartime farming on Boston Common

Plowing up Boston Common before planting vegetables in a World War II “Victory Garden’’ during wartime rationing. I’ve been thinking of Victory Gardens lately as COVID-19-caused supply-chain problems lead many people to consider planting new gardens to supplement their food supplies.

— Robert Whitcomb

Mostly innocent fun

Norumbega Park opened in June 1897. It was built at the behest of the directors of the Commonwealth Avenue Street Railway to try to increase patronage and revenues on the trolley line between Boston and the Auburndale section of Newton. The park's name was taken from the Norumbega Tower, a stone structure that Eben Norton Horsford had built in Weston to mark the purported Norse settlement called Norumbega. The amusement park was closed in 1963 and the ballroom in 1964. The park was a great place for Baby Boomer kids. I went there in 1962 when I was a student in Newton.

— Robert Whitcomb

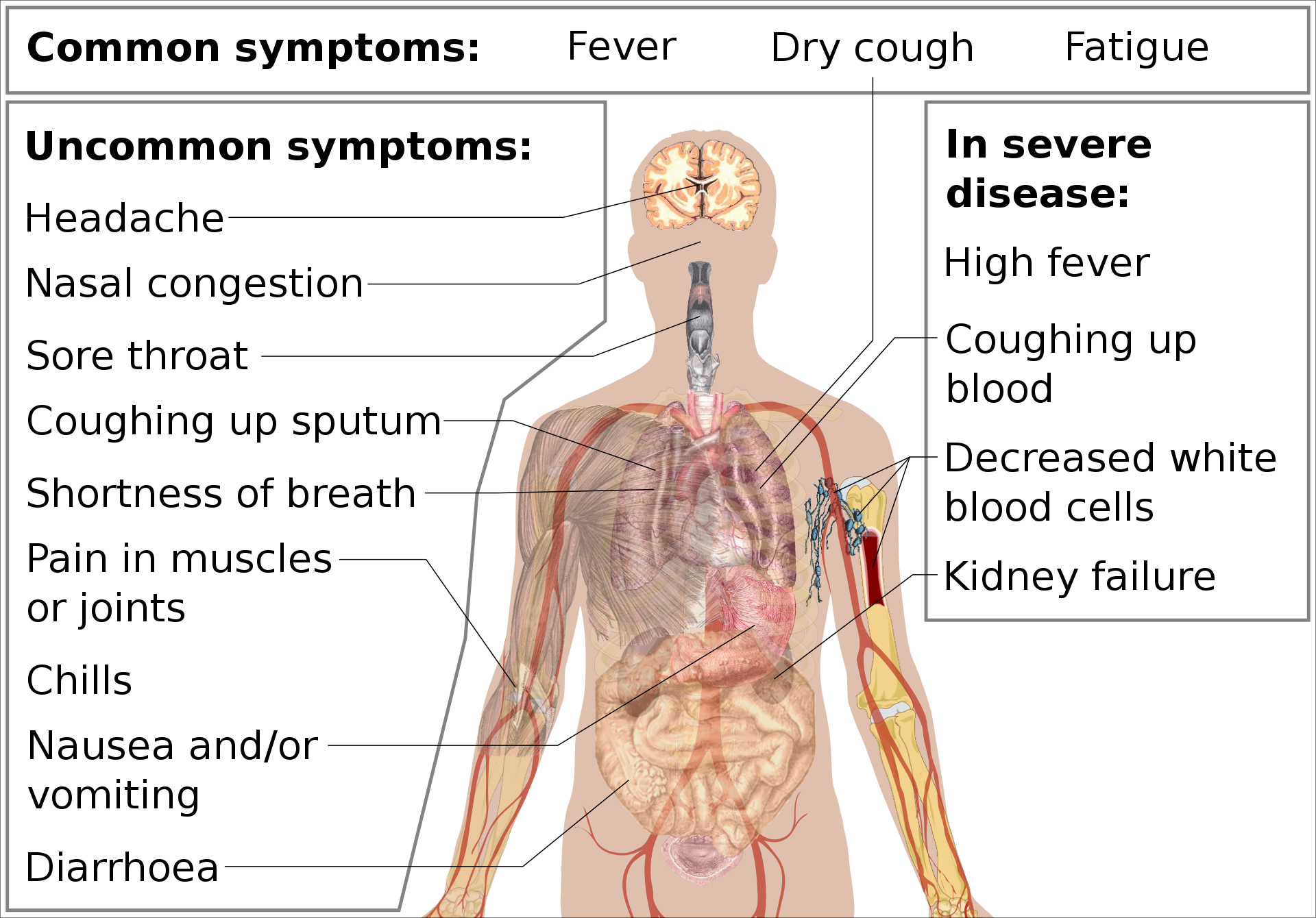

Arthur Waldron: COVID-19 probably originated in a Wuhan lab

Part of the vast city of Wuhan

PHILADELPHIA

Early this just-finished winter, physicians in Wuhan, China, became aware of cases of a new flu-like illness. It was related, as a so-called coronavirus, to the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome virus (SARS). SARS wrought havoc in China in 2003, causing some 8,000 infections, along with a mortality rate of at least 10 percent. It brought martial law to Beijing and elsewhere in China.

The new pathogen, which we’re now getting used to calling COVID-19, is also a coronavirus, thought to be endemic in bats, and transmitted to humans by an as yet unknown pathway (possibly the pangolin, a lovable denizen of the tropics).

The holocaust in China since December has now done previously unimaginable harm, with tens of thousands or more infected in the nation and a death rate comparable to SARS, bringing much of China to a panicky halt. And now there are hundreds of thousands – or more – cases in the world, and many thousands of deaths as the pandemic rolls on.

All of the noble doctors and other health providers who perished, such as Dr. Li Wenliang, who left a child and an infected pregnant wife -- and there were many more -- fearlessly confronted COVID-19, but without one crucial piece of information: namely, how it spread. It was known that the virus could jump from some animals to other animals, and from one person to another, but how exactly did it get from other animals to humans?

Throughout southern China exist hundreds of technically illegal markets, often huge, such as the one in Wuhan, holding wild species, some endangered, that are not legal to sell or eat. But they are consumed anyway. Bats are sold there, and bats are known to harbor the new coronavirus, as do many other unfortunate creatures. A mainstream story developed saying that the viruses jumped from the bats to another species, and thence to people.

The search is on for this creature. However, it probably does not exist and the whole theory about the virus is probably wrong. The simplest explanation for the epidemic is that somehow a form of the new coronavirus, which normally cannot infect human beings, either appeared through natural mutation and spread, or was engineered in a specially protected research facility for just such perilous work.

The epicenter of the infection is in Wuhan, Hubei, China’s great riverine transportation hub, with a population of 11 million — much bigger than New York. A vast wild animal market has long been there. But no way exists to demonstrate that this “wet market” is point zero. Quite the opposite, for a significant number of infections cannot be traced to the animals there.

Also in Wuhan is the Wuhan Institute of Virology and another laboratory configured specifically for such highly dangerous experiments as modifying bacteria and viruses so that they can yield vaccine or be used as biological weapons. These were built over 10 years with French assistance. That French plan for a research partnership fell through but the state-of-the art, level 4 (the highest-security) laboratory remained, and was put to use.

Now we approach the crux of the matter.

The findings of a long-term study, sponsored by the University of North Carolina, were published in Nature in August 2015. Nature is the most authoritative and trusted regular journal publishing new scientific results. Sixteen international experts participated in the study, including Dr. Zheng-li Shi and Dr. Xing-yi Ge, both of the level four laboratory in Wuhan. Here, with some explanation is what they reported:

“. . . We generated and characterized a chimeric virus expressing the spike of bat coronavirus in a mouse-adapted SARS-CoV [coronavirus] backbone. The [result] could] efficiently use multiple orthologs [genetically unrelated variants] of the human SARS receptor, angiotensin converting enzyme II (ACE ) to enter, reproduce efficiently in primary human airways cells, and achieve in vitro titers [sufficiently lethal concentrates] equivalent to epidemic strains of SARS-CoV.”

In other words, using one component of the new coronavirus and another one of SARS, one could create a new virus having a deadliness close to that of SARS and able to cross the species barrier, be fruitful and multiply, killing large numbers of victims, particularly elderly people.

From a virological standpoint this was an important breakthrough in understanding how viruses can propagate into new species. The doctors in the experiments, however, were shocked by its medical implications: Neither monoclonal antibodies nor vaccines killed it. The new virus, which was replicated and christened SHC104, [demonstrated] “robust viral replication, in vitro [lab-ware] and in vivo” [living creatures].

“Our work” the authors noted fearfully, “suggests a potential risk of SARS-CoV emergence from viruses now circulating in bat populations.” It seems likely to me that the new coronavirus did emerge in some such way, as a result of error at the Chinese P4 laboratory. Perhaps the search was for a vaccine. Less likely is that it was the result of research to create a biological weapon, for though such research is widespread worldwide (restarted in 1969 in the United States), the coronavirus is, in one sense, mild: Some people die, but most recover. It is not anthrax.

In any event, I think that an innocent but catastrophic mistake at the Wuhan P4 lab is now bringing something like Götterdämmerung to China.

If components of the new bat virus were connected in the laboratory to those of the known SARS virus, the result was a “virus that could attach functionally to the human SARS receptor, angiotensin converter enzyme II, with which it had similarities but no kinship (“orthologs”). The species barrier was thus crossed with a laboratory-created virus that could copy itself, reproduce in human airways, e.g., the lungs, and produce in glass laboratory equipment the equivalent of titers (amounts of liquid sufficiently concentrated) to achieve the strength of epidemic strains of SARS.

One intriguing piece of evidence appeared very briefly in the Chinese press.

A Southeast Asian editor wrote me:

“I also found this Caixin {Chinese media company} piece interesting. Especially the following paragraph:

{Prof. Richard Ebright, the laboratory director at the Waksman Institute of Microbiology and a professor of chemistry and chemical biology at Rutgers University} “cited the example of the SARS coronavirus, which first entered the human population as a natural incident in 2002, before spiking for a second, third, and fourth time in 2003 as a result of laboratory accidents.”

This article disappeared almost instantly but its contents have been circulating in Southeast Asia.

It indicates that laboratory mishaps were involved in SARS. So the same possibility cannot be ruled out now. The original article has been expunged in China, including from the Caixin archives.

Since then no more technical or scientific evidence has appeared. So we wait for an explanation from the Chinese government.

In China, the fabric of the society is tearing; its foundations and structures are bending and stooping under the lash of a deathly microorganism, apparently made by humans and somehow released, the effects of which few conceived or expected. Now populations of tens of millions around the world face and may well pay the ultimate price. The all-knowing Chinese Communist Party looks absurd and corrupt. In Wuhan supplies are scarce and crematories have worked 24/7 to dispose of the dead. The self-sacrificing medical profession, however, has little idea of where to turn for a cure.

We are in the midst of a global tragedy. Officials of the despotic Chinese government, which designed and built the Wuhan facility, seem ignorant about what they set in motion, while the biologists, with perhaps some exceptions, will recoil, as will subsequent generations, with what they have wrought.

Arthur Waldron is Lauder Professor of International Relations at the University of Pennsylvania and an historian of China. He’s also a longtime friend and colleague of Robert Whitcomb, New England Diary’s editor.

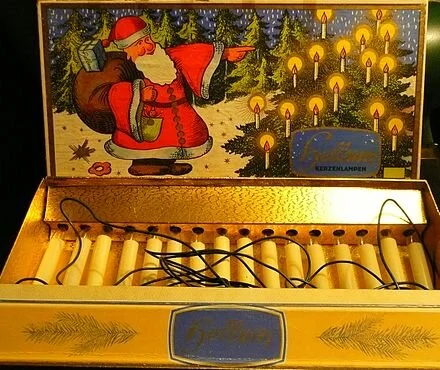

Electric holidays

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

The Christmas season reminds me of the seasonal extension cords lying everywhere in the house I grew up in -- to light the tree, the fake candles in all the windows, a huge Santa Claus face and other displays. The floors in some of the rooms looked as if small snakes were occupying the place. For years, we didn’t stint on these displays. Then, rather suddenly, they didn’t seem worth the trouble. There were some mild shocks along the way, but no one was electrocuted.

A new Pawtucket?

Rendering of the Fortuitous Partners proposal for Pawtucket

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

t’s far too early to know the fate of a Fortuitous Partners proposal to create a $400 million project in downtown Pawtucket that would include a minor league soccer stadium, an “indoor sports event center,’’ apartments, a hotel, offices, shops and restaurants. What will the financing environment look like over the next few years? What if the nation goes into a recession soon? But from what we know now it does look like a better -- and of course much bigger -- project for the city and region than the Pawtucket Red Sox plan to build a new stadium – as sad as the team’s exit is.

The project would leverage people’s love of being along the water – in this case the Seekonk River (which I always think is the Blackstone in that part of Pawtucket) – and presumably heavily promote the project to people from very expensive Greater Boston who might want to live in Pawtucket, further encouraged to do so by the Pawtucket-Central Falls MBTA commuter rail station, scheduled to open in 2022. A big question is how successful the soccer stadium would be, however popular the greatest international sport has become around here, considering that the major league New England Revolution is based just up the road at Gillette Stadium, in Foxboro.

The public part of the financing totals $70 million to $90 million, most of it from a commonly used tax technique called “tax increment financing.’’ This lets developers use part of the tax revenue created by developments to help pay to build them. Also involved in what the developers call “Tidewater Landing’’ are often controversial federal “Opportunity Zone’’ tax breaks that are supposed to encourage economic development in low-income areas but, many note, greatly benefit rich developers. But then, most tax breaks favor the rich. (See below.)

In any case, I hope that this is not one of those projects whose fate is tied in knots in layer upon layer of regulatory red tape. America used to be known for doing big projects; now, big – and needed— projects often seem impossible because of the veto power of too many interest groups, public and private. And there is no such thing as a perfect project. For an overview of our big-project paralysis, using New York’s Penn Station as Exhibit A, please hit this link.