Columbus Day in Victorian Salem

Columbus Day in 1892 at the John Tucker Daland House, in Salem, Mass., long before Native Americans and sympathizers were well organized to educate the general public on how Western Hemisphere indigenous people suffered in many ways in centuries of European colonialization started by the Italian explorer Christopher Columbus. 1892 was before the bulk of Italian immigration to America. Italian-Americans were naturally big fans of the holiday, but it didn’t become an official federal holiday until 1971. Southern New England, of course, drew large numbers of Italian immigrants.

The Daland House, an imposing, Italianate structure designed by architect Gridley James Fox Bryant, is at 132 Essex St. in the Essex Institute Historic District and now owned by the fabulous Peabody Essex Museum as home for the Essex Institute.

The three-story brick house was originally built for John Tucker Daland, a prosperous merchant. The Dalands lived in the house until 1885, when the Essex Institute acquired it. It was then remodeled as offices by architect William Devereux Dennis (1847–1913) and in 1907 connected to the adjacent Plummer Hall (former home of the Salem Athenaeum).

'Portraits' of 'witches'

Installation view of Barbara Broughel’s show ‘‘Requiem,’’ at the Krakow Witkin Gallery, Boston, through Oct. 14.

The gallery explains:

“Barbara Broughel’s ‘Requiem’ portraits consists of brooms and other modest household objects of early American design, each one a ‘portrait’ of a person accused, convicted, and/or executed as a ‘witch’ in 17th Century America. Based on court transcripts, each ‘portrait’ is reconstructed from elements detailing the victim’s life and the ‘spectral evidence’ (whereby an ill-fated event was considered to be caused indirectly through the supernatural powers of a person not present) used to convict them.’’

Salem wasn’t the only place in New England with murderous persecutions. Consider this.

17th Century creepiness

The House of Seven Gables, in Salem, Mass. The first part of the house was built in 1668.

“Halfway down a by-street of one of our New England towns stands a rusty wooden house, with seven acutely peaked gables, facing towards various points of the compass, and a huge, clustered chimney in the midst. The street is Pyncheon Street; the house is the old Pyncheon House; and an elm-tree, of wide circumference, rooted before the door, is familiar to every town-born child by the title of the Pyncheon Elm.”

— Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804-1864), in his novel The House of Seven Gables (1851)

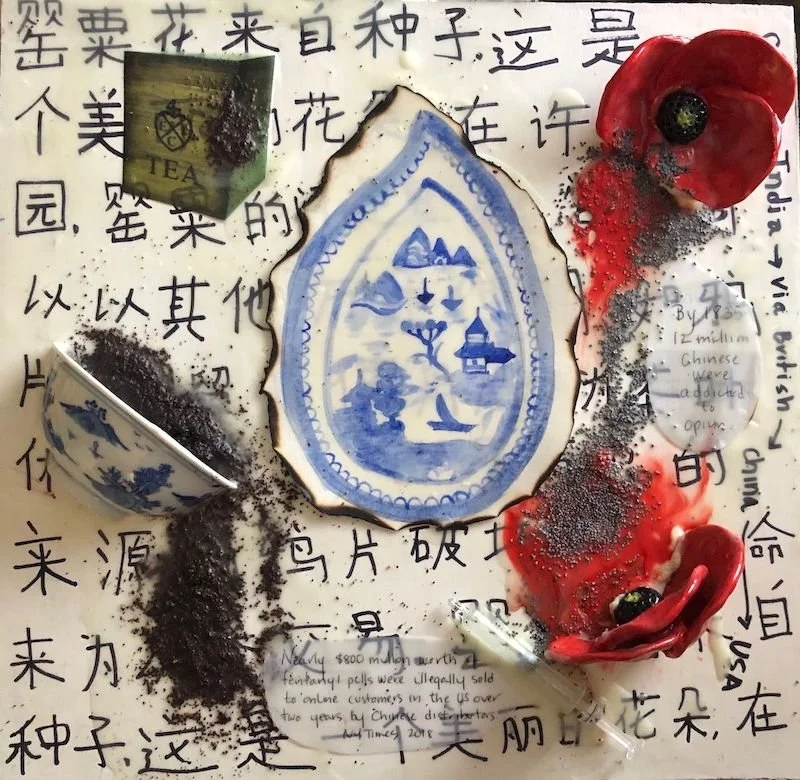

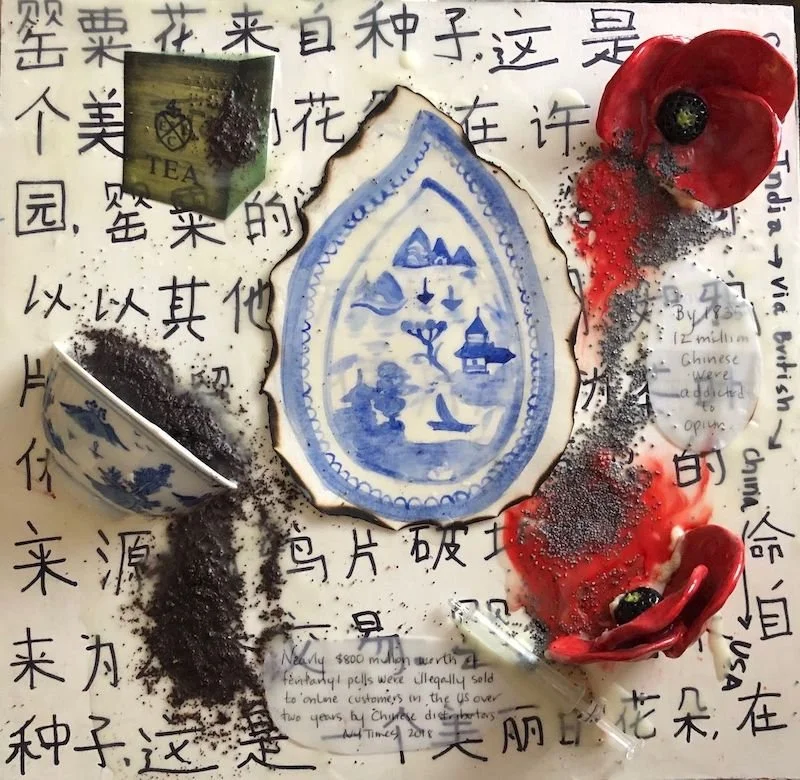

Beauty from New England’s drugged-up China Trade

“China Trade: Opium through the Ages” (encaustic, ceramic made and found objects, tea leaves, poppy seeds on panel), by Cambridge,Mass.-based artist Katrina Abbott.

New England’s “China Trade,’’ in the late 18th Century and the first half of the 19th, created great wealth for some in the region, mostly in and around its ports. Some of the trade involved selling opium to the Chinese. Much of that wealth was invested in what became very lucrative industries, such as textile, shoe and machinery manufacturing and railroads.

In her Web site, Ms. Abbott describes herself thusly:

“Katrina Abbott came to art later in life after her twins were born. Previous to this, she spent 25 years in education, including outdoor education, ocean education at sea and urban public school reform. With a BA in Environmental Biology and a Masters in Botany (studying seaweed!), she reflects her interest in and concern for the natural world in her art. She represents the nature in print, paint, wax ( encaustic) and mosaic. She is a member of the Cambridge Art Association and New England Wax and lives in Cambridge with her husband, their 20 year old boy/girl twins and small brown rabbit named Jarvis.’’

Derby House, in Salem, Mass. Elias Hasket Derby was among the wealthiest and most celebrated of post-Revolutionary War merchants in Salem. He was owner of the Grand Turk, said to be the first New England vessel to be used to trade directly with China. There were many mansions built by merchants in the China Trade, some of which was a drug trade.

—Photo by Daderot

Diner breakfast, then ski

“When I go skiing in New England, I usually wake up early and drive up to Vermont, New Hampshire, or Maine to make it in time for chairlift opening. That means leaving early and getting breakfast at one of the little quaint diners up in the mountains.’’

Sunita Williams (born 1965), American astronaut and U.S. Navy officer who grew up in the Boston area.

She graduated from Needham High School, in Needham, Mass.

On the Upper Wildcat Trail, at the Wildcat Mountain Ski Area, in New Hampshire. The Presidential Range of the White Mountains looms to the west.

Jill Richardson: It’s past time to toss Trump’s huge lies about immigrants

Preparing for an immigrant-naturalization ceremony in Salem, Mass.

Via OtherWords.org

As Donald Trump leaves office, it’s worth remembering how he first launched his campaign: by calling immigrants “murderers” and “rapists.”

This was outrageous then. And there’s more evidence now that it was, of course, false.

A new study finds that “undocumented immigrants have considerably lower crime rates than native-born citizens and legal immigrants across a range of criminal offenses, including violent, property, drug, and traffic crimes.”

The study concludes that there’s “no evidence that undocumented criminality has become more prevalent in recent years across any crime category.” Previous studies found no evidence to support Trump’s claim, but now we have better data than ever before.

Put another way, Trump was telling a dangerous lie.

Sociologists Michael Light, Jingying He and Jason Robey used crime and immigration data from Texas from 2012 to 2018 to find that “relative to undocumented immigrants, U.S.-born citizens are over 2 times more likely to be arrested for violent crimes, 2.5 times more likely to be arrested for drug crimes, and over 4 times more likely to be arrested for property crimes.”

Unfounded accusations of criminality are a longstanding tool of racism and other forms of bigotry across a range of social categories.

When anti-LGBTQ activist Anita Bryant wanted to discriminate against gays and lesbians in the 1970s, she claimed they molested children. More recently, when transphobic people wanted to ban trans women from women’s bathrooms, they falsely claimed that trans women would rape cisgender women in bathrooms.

Consider how much anti-Black racists justified their actions in the name of “protecting white women” from Black men. In 1955, a white woman, Carolyn Bryant Donham, wrongly claimed that a 14-year-old Black boy, Emmett Till, grabbed her and threatened her. White men lynched Till in retaliation. More than half a century later, Donham revealed that her accusations were false.

In 1989, the Central Park Five — five Black and Latino boys between the ages of 14 and 16 — were wrongly convicted and imprisoned for raping a white woman. They didn’t do it. In 2002, someone else confessed and DNA evidence confirmed it. (Trump, who took out full-page ads calling for their execution then, never apologized.)

Racism and bigotry are about power and status. Yet instead of openly admitting that some groups simply want power over others, most bigots find reasons that sound plausible to the uninformed — even if the reasons are completely untrue. Bigotry is much easier to market if it can masquerade as fighting crime.

It wasn’t just Trump himself. During the Trump administration, officials like the U.S. solicitor general argued before the Supreme Court that undocumented immigrants are disproportionately likely to commit crime. Data: None. Claims: False.

As the late New York U.S. Sen Daniel Patrick Moynihan famously said, “You are entitled to your opinion. But you are not entitled to your own facts.”

So when you hear a claim that a particular group of marginalized people are criminals, question it. What is the evidence for the claim? What is the evidence against the claim? Why is the person making the claim, and how will they benefit if people believe them?

If someone cites research, who performed the research, and who funded it? Do the funders have a financial stake in the research findings? Was it published in a peer-reviewed journal? Is the data publicly available for others to replicate the findings?

In this case, the research debunking this racist lie was government-funded, peer-reviewed in a major journal, and the data is available to the public.

Hearing that particular group of people poses a threat to your safety can be frightening. But because such claims have been used throughout history to spread bigotry against marginalized groups, they should always be fact-checked.

In this case, the evidence is clear. Trump stoked anti-immigrant sentiment in the name of fighting crime, and his claims were baseless and false. The lie should end with his presidency.

Jill Richardson is a sociologist.

'Pages of the hillside'

Above and just below, in the Old Burying Point Cemetery, Salem, Mass. It was laid out in 1637.

—Photo by Max Anderson

“The graveyards of New England can be gay or sad, humorous or severe, bleak or beautiful, but they are are always intensely interesting. The spiritual history of our first two hundred years is nowhere written down more clearly than in these slate and granite pages of the hillside, these neglected Americana of the open air.’’

— Odell Shepard, in The Harvest of a Quiet Eye.

Point of Graves Burying Ground, Portsmouth, N.H. It was laid out in the 17th Century.

Fresh visions in close quarters, too

“Owl's Head, Penobscot Bay, Maine,’’ by Fitz Henry Lane, (1804-65), at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Layla Bermeo is the MFA’s Kristin and Roger Servison Associate Curator of Paintings, Art of the Americas. She had this comment on the painting:

‘‘….My attention always lingers on the lone figure in the bottom left, standing with his back turned, holding a pole. Even with the sense of stillness that pervades the canvas, I feel a tension between his immobility and the movement of the ships, which seem to drift away from his gaze, shrinking in the background. This tension is echoed in Lane’s own biography, as he lived with a disability that limited his mobility but spent his career painting ships that traveled very far, very fast.

“As we try to reduce the spread of COVID-19 by restricting our movements, we can feel frozen, watching the rest of the world swirl around us, if not from a shore, then on a screen. But Lane’s work suggests that smaller environments—those we can encounter in a short car drive or neighborhood walk, or even within our own basements or closets—hold greater possibilities than we often notice.

“When scholars reference Lane’s disability, they usually mention what he could not do—he could not study in Europe like other American artists; he could not explore the wilderness like other landscape painters. But he could walk with crutches or a cane, and he did travel across the coasts of Maine and Massachusetts, bringing a fresh vision to the familiar ports of Gloucester, Salem, and Boston. If we stop thinking in terms of what we cannot do, like Lane may have done, how might we see our surroundings differently?”

Elms' gorgeous tunnels

Lafayette Street in Salem, Mass., from a 1910 colorized postcard — an example of the high-tunneled effects of American Elms planted along streets in New England towns. Most of them were gone by the 1950s.

“The elms of New England! They are as much a part of her beauty as the columns of the Parthenon were the glory of its architecture.”

— Henry Ward Beecher (1813-87)

Then came Dutch Elm Disease

Tough customers

The Salem waterfront in the 1770s.

"Remember, seaman, Salem fisherman

Once hung their nimble fleets on the Great Banks.

Where was it that New England bred the men

who quartered the Leviathan's fat flanks

and fought the British Lion to his knees?”

-- From "Salem,'' by Robert Lowell

Salem in 1883, by which time it had become a major industrial town as well as port.

-- Mason, Boston Public Library

200 years to enlightenment

"Examination of a Witch'' (1853,) by T. H. Matteson, inspired by the Salem trials.

"By 1892, enlightenment had progressed to the point where the Salem {witch} trials were simply an embarrassing blot on the history of New England. They were a part of the past that was best forgotten: a reminder of how far the human race had come in two centuries.''

-- Historian Edmund Morgan