Sam Pizzigati: UAW victory’s global significance; next stop Tesla?

On Sept. 20, 1893, Charles and Frank Duryea of Springfield, Mass., built and then road-tested, in that city, the first American gasoline-powered car. During the early years of automobiles, several independent manufacturers built cars in the state. In 1900, Springfield gained Skene American Automobile Co. (based in Springfield but with its factory in Lewiston, Maine) and Knox Automobile. In 1905, Knox produced America's first motorized fire engines, for the Springfield Fire Department. Stevens-Duryea built cars in East Springfield from 1901 to 1915, and again from 1919 to 1927.

Via OtherWords.org

BOSTON

‘Working people the world over have celebrated the first of May as “International Labor Day” since 1886, when workers in the United States struggling for an eight-hour day staged a May 1 national protest.

Thanks to the new deal America’s auto workers have signed with Detroit’s Big Three — Ford, GM and Stellantis — that day could have new global significance. Their watershed new contracts all set April 30, 2028 as their expiration date.

If May 1, 2028 arrives without signed contracts for America’s unionized auto workers, UAW president Shawn Fain has made plain, these workers don’t plan on walking out alone.

“We invite unions around the country to align your contract expirations with our own so that together we can begin to flex our collective muscles,” says Fain. “If we’re going to truly take on the billionaire class and rebuild the economy so that it starts to work for the benefit of the many and not the few, then it’s important that we not only strike but that we strike together.”

But that May 1 day is clearly inviting coordination beyond the national level.

The May Day that workers worldwide have so long honored, Fain notes, has always been “more than just a day of commemoration, it’s a call to action.” And the labor movement worldwide is showing real signs of acting more in strategic concert.

Within the global auto industry, no corporation more embodies the inequality of our corporate world than the non-union Tesla. Under CEO Elon Musk, the world’s richest individual, Tesla pays wages that run substantially below those of Detroit’s Big Three, and that gap will only widen after the new UAW contracts go into effect.

The new UAW contracts, predicts German Bender of the Swedish think-tank Arena, could well “boost union interest among Tesla workers.”

That interest already seems to be growing. On the final Friday of the UAW walkout in the United States, workers at Tesla-owned servicing shops in Sweden went out on strike — after five years of fruitless attempts to get Tesla’s Swedish subsidiary to reach a bargaining agreement. That strike has now spread to all auto shops in Sweden that do work on Tesla cars.

This Swedish walkout represents the first formal strike against Tesla anywhere in the world. And the challenge to Tesla may be spreading. Germany’s largest union, Bloomberg reports, is hoping to organize a 12,000-worker Tesla plant near Berlin.

Tesla’s over 120,000 workers worldwide will see plenty to like in the new UAW contracts in the United States. At Ford, workers who started as temps making $16.67 an hour will automatically move to permanent status and an hourly wage rate of at least $24.91. That rate will hit $40.82 by the contract’s end, and any inflation between now and then will kick that rate higher.

Workers in major American industries haven’t seen gains that stunning since the middle of the 20th century, a time when the chief executives of America’s largest corporations averaged only just over 20 times the compensation of their workers. That gap today, the Economic Policy Institute calculates, is now running nearly 350 times.

But the greatest significance of the new UAW auto industry contracts may be the impact these bargaining triumphs will have on the future. These agreements could become the single most important step to a more equal world that any of us have ever seen.

The giants of American auto manufacturing, as Fain puts it, “underestimated” their own workers’ capacity to unite and fight together.

“We have shown the companies, the American public, and the whole world that the working class is not done fighting,” he adds. “In fact, we’re just getting started.”

Sam Pizzigati, based in Boston, co-edits Inequality.org at the Institute for Policy Studies. His books include The Case for a Maximum Wage and The Rich Don’t Always Win.

Sam Pizzigati: Time to close the huge IRS audit gap that favors the rich

IRS logo

Read about New England’s richest towns, and how they got that way.

Via OtherWords.org

BOSTON

In 2020, U.S. households annually making over $1 million faced fewer tax audits than households with incomes low enough to qualify for the Earned Income Tax Credit. That had never happened before.

In part, you can blame the Trump administration. But conservatives in Congress actually gave Trump his tax-cutting playbook, as a new Americans for Tax Fairness report makes clear.

Ever since 2010, these right-wing lawmakers have been squeezing the IRS budget, forcing the agency “to drastically pull back on auditing the ultra-wealthy.” Between 2010 and 2020, audits on millionaires dropped a whopping 92 percent.

The super rich have taken full advantage. Nearly a thousand taxpayers making over $1 million a year, Sen. Ron Wyden (D.-Ore.) points out, haven’t even bothered “to file tax returns over multiple recent years.”

Thanks to the Inflation Reduction Act President Biden signed, the IRS gained an $80 billion increase in funding last year. Wyden, who chairs the Senate Finance Committee, wants to see the IRS use that money to increase the audit rate on America’s richest.

But Republicans are pushing to chop IRS funding by $67 billion. That cut, Americans for Tax Fairness calculates, would leave the nation right back where the Trump gang left it: with millionaires getting audited less than 1 percent of the time.

We should be resisting those auditing cuts. And besides cracking down on tax cheats, we need to close the wide constellation of loopholes that help the richest Americans legally sidestep any significant tax bill.

One example? The abuse of nonprofit donations.

Most of us hear the word “nonprofit” and think of the Red Cross or some other familiar charity. These traditional charities fall under section 501(c)(3) of the U.S. tax code.

Other nonprofits — most notably those that come under the tax code’s 501(c)(4) — can engage in activities that have next to nothing to do with providing charitable services. They can own companies indefinitely, as Forbes details, and benefit private individuals. They can lobby lawmakers as much as they want and “get directly involved in politics.”

This flexibility that C4s offer became particularly attractive to America’s deepest pockets in 2015.

Lobbyists bankrolled by the billionaire Koch family wiggled into the tax law that year a charming little loophole that lets the rich take shares of stock they own that have appreciated handsomely and pass them to C4s — without having to pay either a gift tax or a capital-gains tax on the share transfer.

The C4s receiving these hefty gifts of shares, Forbes adds, “can then sell the stock, capital gains tax–free, or hold on to it indefinitely, reaping the dividends.”

Thanks to this loophole, note investigative journalists Judd Legum and Tesnim Zekeria, billionaires like Charles Koch can now use their allied C4s “to spend as much money as they want on political campaigns without disclosing their spending or paying taxes.”

Billionaires should be paying taxes like the rest of us to support schools, health care, and the like. Instead, this handy and inequitable loophole leaves billionaires with the wherewithal to buy still more private jets, trinkets, and mansions — and our democracy.

Blank political checks for billionaires like Charles Koch have no place in a country striving to become a more equal place. So let’s fund the IRS, close the loopholes, and conduct those audits. Now!

Sam Pizzigati, based in Boston, co-edits Inequality.org at the Institute for Policy Studies. His books include The Case for a Maximum Wage and The Rich Don’t Always Win.

Sam Pizzigati: Time for a general strike at hyper-rapacious Dollar General

— Photo by Mike Kalasnik

Dollar General headquarters, in Goodlettsville, Tenn.

Via OtherWords.org

BOSTON

President Biden recently walked a picket line in solidarity with striking auto workers. An amazing sight.

What could he do for an encore? He could stand before another major American corporation — Dollar General — holding a simple two-word placard saying “For Shame.”

Thanks to United Auto Workers members and the attention their strike has attracted, Americans now know a bit about the pressures that auto workers face. As a nation, unfortunately, we know next to nothing about life for Dollar General workers.

With more outlets than Walmart and Wendy’s combined, Dollar General has become “America’s most ubiquitous retailer,” Bloomberg reported recently, and may now be the “worst” retail employer in the country.

Bloomberg sums up Dollar General’s corporate ethos this way: “Build as many stores as possible, pack them with tons of stuff while using as little warehouse space as possible, and spend as little as possible on everything else.”

That means spending as little as possible on basic store upkeep.

Businessweek investigators have “found expired products on Dollar General shelves,” from chicken soup in Louisiana to doughnuts in Illinois. In one Oklahoma store, birds nested in the ceiling and pooped down on the merchandise.

And as little as possible on safety.

Government inspectors have reported “fire extinguishers blocked by boxes” and “shaky, leaning towers of product” as high as nine feet tall. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration last year tagged Dollar General a “severe violator” of federal workplace-safety law.

And, of course, Dollar General spends as little as possible on wages and workers.

One of every four Dollar General employees makes less than $10 an hour. Over half make under $12. Meanwhile entire stores go hours every day with only one employee responsible for an average of 7,500 square feet of retail space.

This brutal approach has paid off handsomely for investors and executives. Dollar General’s stock price has quintupled since 2009. And the company reports that its CEO, who hauls in $16.6 million a year, makes 935 more than a “median” Dollar General employee.

Officially, the typical Dollar General worker makes just $17,773 a year. But even that measly figure may be an overstatement.

Researcher Rosanna Weaver reports that the company recently changed its median-pay calculations by “annualizing” the wages of permanent employees who didn’t work a full year. Meanwhile, Dollar General actually understates CEO pay. The company’s executive compensation can run much higher than first reported once executives actually cash out their stock.

One example: After cashing out on a huge chunk of his stock awards, former CEO Todd Vlasos actually made nearly 4,500 times the annual pay of his 163,000 employees. He essentially made more in a single weekday — $328,000 — than his median employee could earn in 18 years.

All this “success” for Dollar General executives rests on a half-century of ever-greater American inequality. For two generations now, a shrinking share of U.S. income and wealth has gone into the pockets of America’s working families.

Thanks to this shrinking share, tens of millions of American families today couldn’t get by without the “bargain-basement” prices that dollar stores like Dollar General offer — at the expense of their customers’ health and safety and the economic security of their workers.

Moreover, that discounted food — often sold in “food-deprived areas” — comes highly processed, offers little in the way of nutritional value, and sits packaged within toxic, chemical-laden wrappings.

“Dollar General’s practices have an immense impact on communities across the country,” note advocacy attorneys Sara Imperiale and Margaret Brown, “especially communities of color and low-income communities.”

The U.S. economy isn’t delivering for American families — and that failure is delivering for corporate investors and executives. You’ll never find them doing their weekly food shopping at Dollar General.

How about a general strike against Dollar General?

Sam Pizzigati, based in Boston, co-edits Inequality.org at the Institute for Policy Studies. His books include The Case for a Maximum Wage and The Rich Don’t Always Win.

Sam Pizzigati: CEO's of defense contractors get very, very rich off taxpayers

The Springfield (Mass.)Armory, more formally known as the United States Armory and Arsenal at Springfield, was the primary center for making U.S. military firearms from 1777 until its closing, in 1968.

At Westover Air Reserve Base, an Air Force Reserve Command (AFRC) installation in the Massachusetts communities of Chicopee and Ludlow. Established at the outset of World War II, Westover is now the largest Air Force Reserve base in the United States, home to about 5,500 military and civilian personnel, and covering 2500 acres.

U.S. Naval Station Newport, in Newport and Middletown, R.I., on Aquidneck Island

Via OtherWords.org

BOSTON

Does anyone have a sweeter deal than military contractor CEOs?

The United States spent more last year on defense than the next 10 nations combined. A deal brokered the other week by the White House and House Republicans increases that amount even further — to $886 billion. Defense contractors will pocket about half of that.

Just eight years ago, the national defense community made do with over $300 billion less. But making do with “less” doesn’t come easy to corporate titans like Dave Calhoun, the CEO at Boeing, the nation’s second-largest defense contractor. Lockheed Martin is the biggest.

In March, Boeing’s annual filings revealed that Calhoun had missed his CEO performance targets and would not be receiving a $7 million bonus. As a result, Calhoun had to be content with a mere $22.5 million in 2022 — but to sweeten the deal, the Boeing board granted their CEO an extra stack of shares worth some $15 million at today’s value.

The Government Accountability Office may have had incidents just like that in mind when it urged the Pentagon to “comprehensively assess” its contract financing arrangements a few years ago.

This past April, the Department of Defense finally attempted to do it.

“In aggregate,” its report concludes, “the defense industry is financially healthy, and its financial health has improved over time.” But despite “increased profit and cash flow,” the DoD found, corporate contractors have chosen “to reduce the overall share of revenue” they spend on R&D.

Instead, they’re “significantly increasing the share of revenue paid to shareholders in cash dividends and share buybacks.” Those dividends and buybacks have jumped by an astounding 73 percent!

Contractor CEOs have been lining their pockets accordingly.

In 2021, the most recent year with complete stats, the nation’s top five weapons makers — Lockheed Martin, Boeing, Raytheon, General Dynamics, and Northrop Grumman – grabbed over $116 billion in Pentagon contracts and paid their top executives $287 million, Pentagon-watcher William Hartung noted this past December.

Taxpayers subsidize these more-than-ample paychecks. Corporate giants like Boeing and Raytheon depend on government contracts for about half the dollars they rake in. For Lockheed Martin, General Dynamics, and Northrop Grumman, it’s at least 70 percent.

“Huge CEO compensation,” Hartung observes, “does nothing to advance the defense of the United States and everything to enrich a small number of individuals.”

Even before Biden and Republicans agreed to increase spending, the National Priorities Project at the Institute for Policy Studies (IPS) calculated the “militarized portion” of the federal budget at 62 percent of all discretionary spending.

We have precious little to show for this enormous expenditure.

“The post-9/11 ‘War on Terror,’ for example, has cost more than $8 trillion and contributed to a horrific death toll of 4.5 million people in affected regions,” the IPS report notes. “Meanwhile, a U.S. military budget that outpaces Russia’s by more than 10 to 1 has failed to prevent or end the Russian war in Ukraine.”

So what can we do? The IPS analysts advocate reducing the national military budget by at least $100 billion and reinvesting the savings in social programs.

Progressive members of Congress, meanwhile, have also been pushing for a major change in contracting standards. Rep. Jan Schakowsky’s (D.-Ill.) “Patriotic Corporations Act” would give companies with smaller pay gaps between their CEOs and workers a leg up in the bidding for federal defense contracts.

Or we could go the Franklin D. Roosevelt route. In the year after Pearl Harbor, FDR issued an order limiting top corporate executive pay to $25,000 after taxes — a move Roosevelt said was needed “to correct gross inequities and to provide for greater equality in contributing to the war effort.”

By the war’s end, America’s wealthy were paying federal taxes on income over $200,000 at a 94 percent rate. That top rate hovered around 90 percent for the next two decades and helped give birth to the first mass middle class the world had ever seen.

Miracles can happen.

Sam Pizzigati, based in Boston, co-edits Inequality.org at the Institute for Policy Studies. His books include The Case for a Maximum Wage and The Rich Don’t Always Win.

Sam Pizzigati: The outrage of child labor is creeping back into the U.S.

"Addie Card, 12 years. Spinner in North Pormal Cotton Mill, Vt." by Lewis Hine, 1912.

Via OtherWords.org

BOSTON

Ever since the middle of the 20th century, our history textbooks have applauded the reform movement that put an end to the child-labor horrors that ran widespread throughout the early Industrial Age.

Now those horrors are reappearing.

The number of kids employed in direct violation of existing child labor laws, the Economic Policy Institute reported this year, has soared 283 percent since 2015 — and 37 percent in just the last year alone.

More recently there was the alarming news that three Kentucky-based McDonald’s franchising companies had kids as young as 10 working at 62 stores across Kentucky, Indiana, Maryland, and Ohio. Some children were working as late as 2 a.m.

Federal legislation to crack down on child labor has stalled out amid Republican opposition. And at the state level, lawmakers across the country are moving to weaken — or even eliminate — child labor limits.

One bill in Iowa introduced earlier this year would let kids as young as 14 labor in workplaces ranging from meat coolers to industrial laundries. And Arkansas just eliminated the requirement to “verify the age of children younger than 16 before they can take a job,” the Washington Post reported.

Over a century ago, in the initial push against child labor, no American did more to protect kids than the educator and philosopher Felix Adler. In 1887, Adler sounded the alarm on child labor before a packed house at Manhattan’s famed Chickering Hall.

The “evil of child labor,” Adler warned, “is growing to an alarming extent.” In New York City alone, some 9,000 children as young as eight were working in factories. Many of those kids, Alder said, “could not read or write” and didn’t even know “the state they lived in.”

By the end of 1904, as the founding chair of the National Child Labor Committee, Adler had broadened the battle against exploiting kids. He railed against the “new kind of slavery” that had some 60,000 children under 14 working in Southern textile mills up to 14 hours a day, up from “only 24,000” just five years earlier.

Adler put full responsibility for this exploitation on those he called America’s “money kings,” who he said were after “cheap labor.” Alongside his campaigns to limit child labor, Adler pushed lawmakers to end the incentives that drive employers to exploit kids.

Aiming to prevent the ultra rich from grabbing all the wealth they could, Adler called for a tax rate of 100 percent on all income above the point “when a certain high and abundant sum has been reached, amply sufficient for all the comforts and true refinements of life.”

After the United States entered World War I, the national campaign for a 100-percent top income-tax rate on America’s highest incomes had a remarkable impact. In 1918, Congress raised the nation’s top marginal income tax rate up to 77 percent, 10 times the top rate in place just five years earlier.

During World War II, President Franklin Roosevelt renewed Adler’s call for a 100-percent top tax rate on the nation’s super rich. By the war’s end, lawmakers had okayed a top rate — at 94 percent — nearly that high. By the Eisenhower years, that top rate had leveled off at 91 percent.

Felix Adler died in 1933, before he could see the full scope of his victory. But by the mid-20th Century those inspired by him had won on both his key advocacy fronts. By the 1950s, America’s rich could no longer keep all they could grab, and masses of mere kids no longer had to labor so those rich could profit.

The triumphs thatAdler helped animate have now come undone. We need to recreate them.

Sam Pizzigati, based in Boston, co-edits Inequality.org at the Institute for Policy Studies. His books include The Case for a Maximum Wage and The Rich Don’t Always Win.

1900 ad for McCormick farm machines

#child labor

Sam Pizzigati: The best case yet for raising taxes on billionaires

“Spirit of Ecstasy,” the bonnet ornament sculpture on Rolls-Royce cars, for which there were record sales last year.

— Photo by Jed

Via OtherWords. org

BOSTON

Sometimes the daily news about our billionaires just doesn’t make sense.

Last year, for instance, ended with a torrent of news stories about how poorly the world’s billionaires fared in 2022. Bloomberg tagged the 12 months that had just gone past “a year to forget,” with almost $1.5 trillion “wiped from the fortunes of the richest 500 alone.”

All global billionaires taken together, Forbes chimed in, lost $1.9 trillion in 2022. Some 148 of the world’s 2,671 billionaires even lost their billionaire status.

The year’s biggest billionaire losers? Some of America’s deepest pockets.

Larry Page saw his Google-driven fortune drop $40 billion. Mark Zuckerberg watched $78 billion evaporate off the wealth Facebook created for him. And Amazon’s Jeff Bezos had to swallow a minus $80 billion.

But honors for the biggest nosedive of all have to go to Elon Musk. The world’s richest man at the start of 2022, Musk ended the year losing both his top slot and some $115 billion from his personal fortune.

So did all these losses have our billionaires shaking in their boots? Did they start tightening their belts a bit in 2022? Spend less on the world’s most fabulously expensive luxuries?

Not exactly. In fact, not all.

The world’s most celebrated purveyors of pure extravagance actually registered record years in 2022. Rolls-Royce had its best-ever annual sales total, selling a record 6,021 “motor cars,” up 8 percent over 2021.

“Our clients,” Rolls-Royce’s CEO crowed on New Year’s Day, “are now happy to pay around half a million Euros for their unique motor car,” a sum equal to about $540,000 in the United States, the company’s single largest market.

“Our order book stretches far into 2023 for all models,” the Rolls-Royce chief added. “We haven’t seen any slowdown in orders.”

Lamborghini had an even better 2022, with 9,233 vehicles sold — a 10-percent jump over last year. The company’s biggest market? The United States. Americans drove off Lamborghini lots with 2,771 new cars in 2022. The automaker’s most popular model runs about a quarter-million.

Realtors who cater to the ultra-rich set had an equally boffo year in 2022.

In a down real-estate market, the highest of high-end residences still pulled in mega sums at closing time. The year’s top 10 home sales in the United States, notes the luxury-oriented Robb Report, “totaled roughly $1.165 billion, proving that, impending recession or not, luxury real estate will always be traded.”

How can all this luxury be? How can the richest of the rich be spending fantastic sums in a year when they’re seeing fantastic falls in their personal net worths?

Simple. In the realms of the super rich, losing a billion — or even many billions — makes no difference whatsoever in real daily life. Net worth down a few billion? You can still afford anything your heart could possibly desire.

No one alive today needs fortunes worth dozens of billions to live astoundingly large. A mere billion would suffice. So, truth be told, would a mere tenth of a billion. In the day-to-day lives of billionaires, a few billions or so have no practical significance — except when it comes to increasing their political power at the expense of the rest of us.

Taxing those billions to support the common good, on the other hand, could make an immeasurable difference in the lives of millions — and our democracy.

We need more than a dip in grand concentrations of private wealth. We need a world without billionaires.

Sam Pizzigati, based in Boston, co-edits Inequality.org at the Institute for Policy Studies. His books include The Case for a Maximum Wage and The Rich Don’t Always Win.

Sam Pizzigati: Maybe taxpayer-subsidized Musk isn’t quite as brilliant as you think

Elon Musk

— Photo by Debbie Rowe

BOSTON

From OtherWords.org

A good day’s work for a good day’s pay. Should this age-old wisdom apply to overpaid CEOs as well as their workers? A Delaware court will soon decide, a turn of events that must have the richest man in the known universe, Elon Musk, feeling more than a little bit uneasy.

Delaware’s little-known Court of Chancery normally provides business moguls a battleground where they can slug out their big-ticket differences. But the court also gives stockholders a chance to push back against the moguls — and one modest shareholder in the Musk empire has done just that.

Shareholder Richard Tornetta, a former heavy-metal drummer, filed suit in 2018 against the company’s board for lavishing unnecessary billions upon Musk.

Tornetta’s challenge has ended up before the Chancery Court’s Kathleen McCormick, a judge who’s already demonstrated a distinct lack of patience with Muskian antics. Just this past October, McCormick ruled against Musk in another case. She might well again.

Musk’s current Tesla CEO pay plan, notes CNN Business, gives Musk “the largest compensation package for anyone on Earth from a publicly traded company.” Under the plan, the higher Tesla’s share price goes, the more new Tesla shares Musk gets.

Thanks to that connection, Musk’s personal net worth now sits at $189 billion, the world’s largest personal fortune. In 2018, the year Musk’s Tesla pay deal went into effect, some 40 billionaires worldwide topped Musk on the Bloomberg billionaire charts.

Back in 2018, major shareholder advisory firms recommended that Tesla shareholders reject the pay deal that Tesla’s corporate board — a panel that included Musk’s brother and assorted close pals — wanted to give Musk.

Musk himself, one advisory firm noted, already had plenty of incentive to work hard for Tesla’s success. He owned 22 percent of Tesla’s shares even before his new CEO pay deal.

The week-long trial on Richard Tornetta’s Delaware lawsuit against Musk and Tesla ended in mid-November. Judge McCormick’s decision in the case will likely come down sometime over the next three months.

McCormick’s previous ruling against Musk came when the billionaire tried to back out of the deal he cut last spring to buy Twitter. After that ruling, Musk had to go ahead with the purchase. Now he’s flailing about, trying to make others pay the price for his impulsive takeover bid. He’s already laid off half the Twitter workforce.

If McCormick rules against Musk once again, Musk will still walk away fantastically rich. But he won’t walk away happy. His ongoing Twitter debacle — and now the Tesla litigation — have dealt his reputation for unparalleled business “genius” a potentially fatal blow.

Under cross-examination in the Tesla case, for instance, Musk had to concede that he didn’t come up with the original vision for Tesla himself, the claim he’s been making for years.

Musk turns out to be as flawed as the rest of us. The key difference: Musk has the power and wealth to make others pay for his mistakes.

Musk has also benefited, unlike the rest of us, from billions in taxpayer subsidies. Handouts to his electric car, solar panel and spaceflight businesses — all “long-shot start-ups,” the Los Angeles Times has detailed — gave his companies their secret sauce. Those subsidies launched Musk’s unparalleled personal fortune.

So what can the rest of us do to prevent another “brilliant” entrepreneur from building a fortune off the insights, labor and tax dollars of others? We can deny subsidies to companies that pay their top execs hundreds of times more than what they pay their workers. We can tax the rich at much higher rates.

And we can put Elon Musk atop a rocket and send him off to where he has repeatedly announced he dearly wants to go — to Mars.

Sam Pizzigati, based in Boston, co-edits Inequality.org at the Institute for Policy Studies. His books include The Case for a Maximum Wage and The Rich Don’t Always Win.

Sam Pizzigati: Time for a Tom Paine tax program

BOSTON

From OtherWords.org

The great pamphleteer of the American Revolution, Thomas Paine, had much more on his mind than independence from the British.

Paine spent his life, Jeremy Bearer-Friend and Vanessa Williamson write in a new paper, advocating for a democratic “commonwealth” that shared the wealth. He wanted to free people “from domination both political and economic.”

In particular, Paine believed that a wealth tax on grand private fortunes could prevent the emergence of an anti-democratic elite. This tax season, over two centuries later, we may finally have a president who’s taking Paine to heart.

In its new budget proposal, the Biden administration is calling for a new “Billionaire Minimum Income Tax.” The White House isn’t calling this proposal a “wealth tax,” but we should.

Under Biden’s plan, Americans worth over $100 million would be expected to pay an annual tax of at least 20 percent on their total income — including any increases in the value of their stocks, bonds, and other liquid assets.

These liquid assets make up the bulk of every billionaire fortune, but increases in their value go totally untaxed until their wealthy owners decide to sell them off. That gives “ultra-high-net-worth households,” the White House points out, the ability to have their gains “go untaxed for decades or generations.”

Let’s take the example of a CEO who pockets $20 million a year in salary. He might pay a 20 percent tax on that $20 million.

But if this executive also holds stocks worth $10 billion and those stocks gain 10 percent in value — an extra $1 billion — then the vast majority of our CEO’s real income would go completely untaxed.

Under Biden’s plan, that CEO would have to pay taxes on his CEO pay and all his stock gains. That would hike his federal tax tab from $4 million to $204 million.

America’s 700 or so billionaires, the Biden administration notes, saw “their wealth increase by $1 trillion” last year. Yet current law has billionaires paying “just 8 percent of their total realized and unrealized income in taxes.”

That’s right: Billionaires pay at a lower overall rate than average Americans.

“Under current law, when an American worker earns a dollar of wages, that dollar is taxed as they earn it,” the White House explains. “But when a billionaire earns income because their investments increase in value, that gain is too often never taxed at all.”

Firefighters and teachers, adds the White House, “can pay double” the rate billionaires pay.

The Biden tax plan is actually taking much the same approach that Tom Paine took with a wealth tax proposal he first put forward in 1792, tax historians Bearer-Friend and Williamson argue.

Under Paine’s plan, the pair calculate, today’s billionaires would pay a tax of about 3.5 percent of their personal fortunes during normal market years. That figure is remarkably close to the tax rates that appear in wealth tax proposals that Senators Elizabeth Warren (D.-Mass) and Bernie Sanders (I.-Vt.) have advanced.

Biden’s plan doesn’t take that big a bite. But it does represent a significant step toward taxing the wealth of America’s wealthiest, says Berkeley economist Gabriel Zucman.

Mega-billionaires Jeff Bezos, Warren Buffett, and Elon Musk, Zucman reminds us, together paid just $1.5 billion in federal income taxes over the five-year period that ended in 2018. Under the Biden proposal, this trio would pay at least 100 times more over the next decade or so.

Paine believed that extreme wealth undermines “the ability of citizens to choose their leaders,” Bearer-Friend and Vanessa Williamson argue, a condition that many will easily recognize today. Freedom, in Paine’s view, “meant both lifting the poor from penury and dependence” and eliminating the “vicious influence” of fiercely concentrated wealth.

Tom Paine had it right. And if Congress takes up Biden’s new tax plan, we can too.

Sam Pizzigati, based in Boston, co-edits Inequality.org at the Institute for Policy Studies. His latest books include The Case for a Maximum Wage and The Rich Don’t Always Win.

Sam Pizzigati: Amazon’s business model can kill

From OtherWords.org

BOSTON

Old-school home-improvement contractors have a piece of folk wisdom they love to share with prospective clients. “Listen,” they like to say. “I can do this job fast, I can do it cheap, or I can do it well. But I can’t do all three.”

This wisdom has been around forever. But not everyone gets it — take billionaire Jeff Bezos. His Amazon empire prides itself on delivering good results fast and cheap.

That works well enough for Bezos, now worth around $200 billion. And Amazon consumers, the company PR maintains, can get almost whatever they want quickly and cheaply. But for Amazon workers — and our broader society — Amazon’s empire building has been anything but good.

That became disastrously apparent this month, when a tornado swept through Edwardsville, Ill., leaving six Amazon warehouse workers dead. Debris from their workplace turned up “tens of miles” away, the National Weather Service reported.

Unfortunately, this tragedy should not have taken anyone by surprise.

Why did Amazon locate its Edwardsville operations right in Tornado Alley? No mystery there. Edwardsville’s plentiful acreage and easy access to interstate highways, airports, and other transport offered Amazon the promise of speedy delivery times and lower delivery costs.

Check fast. Check cheap. But the warehouse went up with no special attention to tornado safety. That would have raised the cost.

OSHA — the federal occupational health and safety agency — has now begun an investigation. Since the deaths in Edwardsville, Amazon workers throughout the southern Illinois area have been ripping the company for failing to conduct tornado drills and expecting workers to keep working even after alarms ring out.

Amazon’s “storm shelter” spaces for Edwardsville workers turned out to have another name: bathrooms. Moments before the tornado’s arrival, Edwardsville worker Craig Yost told local news, Amazon supervisors were directing people into their worksite’s bathroom “shelters.”

“The walls caved in, and I got pinned to the ground by a giant block of concrete,” Yost said. “On top of my left knee was a door from the bathroom stall, and my head was on that with my left arm wrapped around my head. I could just move my right hand and foot.”

Meanwhile, the company has been actively exercising its considerable power to prevent the one turn of events that could reliably keep Amazon on its safety toes: a union. Earlier this year, Amazon quashed a union drive at its Bessemer, Ala., warehouse so egregiously that the National Labor Relations board has ordered a do-over on the election.

But the problem goes beyond Amazon. Our nation’s corporate giants have been on a ferocious 50-year offensive against collective bargaining.

In the mid-20th Century, over a third of America’s private-sector workers belonged to unions. Now only 6.3 percent of private-sector workers carry union cards, despite polling data showing that the share of nonunion workers who want a union at their worksite has increased markedly.

Corporate America’s squeeze on unions has kept wages low, share prices high and compensation for top executives at stratospheric levels. Earlier this year, Institute for Policy Studies research revealed that CEOs at America’s 100 largest low-wage employers saw their personal compensation jump by $1,862,270 in 2020.

Over the past year, Jeff Bezos has seen his wealth soar by over $4 billion — seven times the annual budget of OSHA, the agency investigating the disaster at his Edwardsville warehouse. So here’s an idea for lawmakers in Washington: A 5 percent annual federal wealth tax on those Bezos billions could quadruple the annual OSHA budget — and then quadruple it again.

Amazon’s relentless quest to sell goods fast and cheap has rewarded Bezos tremendously, but it’s come at a huge cost for the rest of us. If the company rebuilds its Edwardsville warehouse, Bezos should listen to his handyma\

Sam Pizzigati, who is based in Boston, co-edits Inequality.org at the Institute for Policy Studies. His latest books include The Case for a Maximum Wage and The Rich Don’t Always Win.

Sam Pizzigati: War is wonderful for American military contractors

Raytheon headquarters in Waltham, Mass.

Via OtherWords.org

BOSTON

In the 21st Century, many of us are used to the murderous mass violence of modern warfare.

After all, we grew up living it or hearing about it. The 20th Century rates as the deadliest in human history — 75 million people died in World War II alone. Millions have died since, including a quarter-million during the 20-year U.S. war in Afghanistan.

But for our forebears, the incredible deadliness of modern warfare came as a shock.

The carnage of World War I — with its 40 million dead — left people scrambling to prevent another horror. In 1928, the world’s top nations even signed an agreement renouncing war as an instrument of national policy.

Still, by the mid-1930s the world was swimming in weapons, and people wanted to know why.

In the United States, peace-seekers followed the money to find out. Many of America’s moguls, they learned, were getting rich off prepping for war. These “merchants of death” had a vested interest in the arms races that make wars more likely.

So a campaign was launched to take the profit out of war.

On Capitol Hill, Senate Democrats set up a committee to investigate the munitions industry and named a progressive Republican, North Dakota’s Gerald Nye, to chair it. “War and preparation for war,” Nye noted in 1934, had precious little to do with “national defense.” Instead, war had become “a matter of profit for the few.”

The war in Afghanistan offers but the latest example.

We won’t know for some time the total corporate haul from the Afghan war’s 20 years. But Institute for Policy Studies analysts Brian Wakamo and Sarah Anderson have come up with some initial calculations for three of the top military contractors active in Afghanistan from 2016-2020.

They found that total compensation for the CEOs alone at these three corporate giants — Fluor, Raytheon and Boeing — amounted to $236 million.

A modern-day, high-profile panel on war profiteering might not be a bad idea. Members could start by reviewing the 1936 conclusions of the original committee.

Munitions companies, it found, ignited and exacerbated arms races by constantly striving to “scare nations into a continued frantic expenditure for the latest improvements in devices of warfare.”

“Wars,” the Senate panel summed up, “rarely have one single cause,” but it runs “against the peace of the world for selfishly interested organizations to be left free to goad and frighten nations into military activity.”

Do these conclusions still hold water for us today? Yes — and in fact, today’s military-industrial complex dwarfs that of the early 20th century.

Military spending, Lindsay Koshgarian, of the IPS National Priorities Project, points out, currently “takes up more than half of the discretionary federal budget each year,” and over half that spending goes to military contractors — who use that largesse to lobby for more war spending.

In 2020, executives at the five biggest contractors spent $60 million on lobbying to keep their gravy train going. Over the past two decades, the defense industry has spent $2.5 billion on lobbying and directed another $285 million to political candidates.

How can we upset that business as usual? Reducing the size of the military budget can get us started. Reforming the contracting process will also be essential. And executive pay needs to be right at the heart of that reform. No executives dealing in military matters should have a huge personal stake in ballooning federal spending for war.

One good approach: IIlinois Rep. Jan Schakowsky’s Patriotic Corporations Act.

Among other things, that proposed law would give extra points in contract bidding to firms that pay their top executives no more than 100 times what they pay their most typical workers. Few defense giants come anywhere close to that ratio.

War is complicated, but greed isn’t. Let’s take the profit out of war.

Boston-based Sam Pizzigati co-edits Inequality.org at the Institute for Policy Studies. His latest books include The Case for a Maximum Wage and The Rich Don’t Always Win.

Sam Pizzigati: Ego-space-tripping billionaires want more tax breaks

Jeff Bezos’s space-project production facilities near the Kennedy Space Center, in Florida

— Photo by MadeYourReadThis

Via OtherWords.org

BOSTON

Three of the richest billionaires on Earth are now spending billions to exit Earth’s atmosphere and enter into space. The world is watching — and reflecting.

Some charmed commentators say the billionaires racing into space aren’t just thrilling humankind — they’re uplifting us. The technologies they develop “could benefit people worldwide far into the future,” says Yahoo Finance’s Daniel Howley.

But most commentators seem to be taking a considerably more skeptical perspective.

They’re dismissing the space antics of Richard Branson, Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk as the ego trips of bored billionaires — “cynical stunts by disgustingly rich businessmen,” as one British analyst puts it, “to boost their self-importance at a time when money and resources are desperately needed elsewhere.”

“Space travel used to be about ‘us,’ a collective effort by the country to reach beyond previously unreachable limits,” writes author William Rivers Pitt. “Now, it’s about ‘them,’ the 0.1 percent.”

The best of these skeptical commentators can even make us laugh.

“Really, billionaires?” comedian Seth Meyers asked earlier this month. “This is what you’re going to do with your unprecedented fortunes and influence? Drag race to outer space?”

Let’s enjoy the ridicule. But let’s not treat the billionaire space race as a laughing matter.

Let’s see it as a wake-up call — a reminder that we don’t only get billionaires when wealth concentrates. We get a society that revolves around the egos of the most affluent and an economy where the needs of average people don’t particularly matter.

Characters like Elon Musk, notes Paris Max, host of the Tech Won’t Save Us podcast, are using “misleading narratives about space to fuel public excitement” and gain tax-dollar support for various projects “designed to work best — if not exclusively — for the elite.”

The three corporate space shells for Musk, Bezos and Branson — SpaceX, Blue Origin and Virgin Galactic — have “all benefited greatly through partnerships with NASA and the U.S. military,” notes CNN Business. Their common corporate goal: to get satellites, people, and cargo “into space cheaper and quicker than has been possible in decades past.”

Branson is hawking tickets for roundtrips “to the edge of the atmosphere and back” at $250,000 per head. He’s planning some 400 such trips a year, observes British journalist Oliver Bullough, about “almost as bad an idea as racing to see who can burn the rainforest quickest.”

The annual U.N. Emissions Gap Report last year concluded that the world’s richest 1 percent do more to foul the atmosphere than the entire poorest 50 percent combined. Opening space to rich people’s joyrides would stomp that footprint even bigger.

Bezos and Musk seem to have grander dreams than mere space tourism — they’re looking to colonize space. They see space as a refuge from an increasingly inhospitable planet Earth. And they expect tax-dollar support to make their various pipe dreams come true.

How should we respond to all this?

We should, of course, be working to create a more hospitable planet for all humanity. In the meantime, advocates are circulating tongue-in-cheek petitions that urge terrestrial authorities not to let orbiting billionaires back on Earth.

“Billionaires should not exist…on Earth or in space, but should they decide the latter, they should stay there,” reads one Change.org petition nearing 200,000 signatures.

Ric Geiger, the 31-year-old automotive-supplies account manager behind that effort, is hoping his petition helps the issue of maldistributed wealth “reach a broader platform.”

Activists like Geiger are going down the right track. We don’t need billionaires to “conquer space.” We need to conquer inequality.

Sam Pizzigati, based in Boston, is an associate fellow and co-editor of Inequality.org at the Institute for Policy Studies. He’s the author of The Rich Don’t Always Win and The Case for a Maximum Wage.

This op-ed was adapted from Inequality.org and distributed by OtherWords.org.

Sam Pizzigati: Biden’s Roosveltian tax-the-rich plan

Via OtherWords.org

BOSTON

President Joe Biden has made no secret of his admiration for Franklin D. Roosevelt. The president proudly displays a portrait of FDR in the Oval Office.

More significantly, he’s announced the most ambitious plan since FDR’s New Deal for enhancing the well-being of working Americans while trimming the fortunes of America’s super rich. The president has promised to fund his big plans for infrastructure, jobs and education entirely with taxes on the top.

In fact, Biden’s new tax-the-rich plan is a good deal more Rooseveltian than the numbers, at first glance, might suggest.

In 1945, when FDR died in office, the nation’s most affluent faced a 94 percent tax on income over $200,000, a little more than $2.9 million in today’s dollars. The rates Biden has proposed come nowhere near those — they’d top out at just 39.6 percent of ordinary income over $400,000. That’s up only slightly from the current 37 percent.

But the gap between Biden’s plan and FDR shrinks big-time when we toss capital gains — the dollars the rich make buying and selling stocks and bonds, property, and other assets — into the picture.

In 1945, the nation’s deepest pockets paid a 25 percent tax on their capital-gains windfalls. Today’s rate tops off at 20 percent. For households making over $1 million in annual income, the Biden plan would raise the top capital- gains tax rate to 39.6 percent, the same top rate that applies to earnings from employment.

In other words, the Biden tax plan ends the most basic tax break for the ultra rich: the preferential treatment they get on the income from their wheeling and dealing. This would be a big deal. In 2019, 75 percent of the benefits from the capital-gains tax break went to America’s top 1 percent.

Dividends currently get the same preferential treatment. Americans making over $10 million in 2018 took in over half of their total incomes — 54 percent — via capital gains and dividends. If Congress adopts the Biden tax plan, the basic federal tax on that 54 percent would just about double, from 20 to 39.6 percent.

The Biden plan also totally eliminates the federal tax code’s open invitation to dynastic family wealth: the “step up” loophole. Under this notorious giveaway, any fabulously wealthy American sitting on unrealized capital gains can pass those gains onto heirs tax-free. The Biden plan short-circuits the simplest route to dynastic fortune.

Under Biden’s tax plan, new dynastic fortunes would have a much harder time taking root. Already existing dynastic fortunes, on the other hand, would still be with us. Biden — like FDR in his day — has not yet warmed to the idea of a wealth tax.

Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren led a recent hearing highlighting the enormous contribution that even a 2 percent annual tax on grand fortunes could make. Among the insightful witnesses at the hearing: the 61-year-old Abigail Disney, the granddaughter of Roy Disney, the co-founder of the Disney empire with his brother Walt.

“I can tell you from personal experience,” Abigail Disney told senators, “that too much money is a morally corrosive thing — it gnaws away at your character… It warps your idea of how much you matter, and rather than make you free, it turns you fearful of losing what you have.”

Franklin Roosevelt understood that debilitating dynamic well enough to propose, in 1942, a 100 percent tax on annual income over what today would be about $400,000. Biden hasn’t ventured anywhere close to that level of daring. But he’s certainly come much further than anyone could reasonably have expected.

Sam Pizzigati is the Boston-based co-editor of Inequality.org and author of The Case for a Maximum Wage and The Rich Don’t Always Win.

Sam Pizzigati: Walgreens workers take the pandemic risks as chain's senior execs get even richer

A Walgreens store on Route 1 in Saugus, Mass.

Via OtherWords.org

BOSTON

Every week, millions of us walk into a Walgreens drugstore without giving it a second thought.

Maybe we should. Walgreens perfectly encapsulates the long-term economic trends of the Trump years: top corporate executives pocketing immense paychecks at the expense of their workers.

At Walgreens, workers start at just $10 an hour. No chain-store empire employing essential workers pays less.

And no retail giant in the United States has given its workers less of a pandemic hazard pay bump — just 18 cents an hour, according to Brookings analysts Molly Kinder and Laura Stateler.

These paltry numbers look even worse when we turn our attention to the power suits who run Walgreens, who face no pandemic hazard. Walgreens CEO Stefano Pessina took home $17 million last year. Altogether, the five top Walgreens execs averaged $11 million for the year, a 9 percent hike over the previous year’s annual average.

Meanwhile, the typical Walgreens employee pulled down a mere $33,396. Pessina’s take-home outpaced that meager reward by 524 times. In effect, Pessina made more in a single weekday morning than his company’s typical worker made for an entire year.

Kinder and Stateler found similar levels of greed at other U.S. retail giants, especially Amazon and Walmart. Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos and the heirs to the Walmart fortune, they note, “have grown $116 billion richer during the pandemic — 35 times the total hazard pay given to more than 2.5 million Amazon and Walmart workers.”

Amazon and Walmart, they add, “could have quadrupled the extra COVID-19 compensation they gave to their workers” and still earned more profit than the previous year.

Not every major corporate player has treated the pandemic as just another easy greed-grab. Workers at Costco — who start at $15 an hour, $5 an hour more than workers at Walgreens — got an extra $2 an hour in hazard pay.

Costco’s top executive team, interestingly, last year collected less than half the pay that went to their counterparts at Walgreens. Costco’s most typical workers took home $47,312 for the year. At 169 to one, that’s less than one-third the pay gap between Walgreen’s chief exec and his company’s most typical workers.

As a society, which corporations should we be rewarding — those whose executives enrich themselves at worker expense, or those that value the contributions all their employees are making?

In moments of past national crises, like World War II, lawmakers took action to prevent corporate profiteering. They put in place stiff excess profits taxes. We could act in that same spirit today. We could, for instance, raise the tax rate on companies that pay their top execs unconscionably more than their workers.

We could also start linking government contracts to corporate pay scales: no tax dollars to any corporations that pay their CEOs over a certain multiple of what their workers take home.

Efforts to link taxes and contracts to corporate pay ratios have already begun.

Voters in San Francisco this past November opted to levy a tax penalty on corporations with top executives making over 100 times typical San Francisco worker pay. Portland, Oregon took a similar step in 2018. At the national level, progressive lawmakers have introduced comparable legislation.

Donald Trump may be gone, but the executives who did so well throughout his tenure remain in place. We need to change the rules that flatter their fortunes.

Sam Pizzigati, based in Boston, is the co-editor of Inequality.org and author of The Case for a Maximum Wage and The Rich Don’t Always Win.

Sam Pizzigati: Biden tax plan would reduce inequality

“The tax collector's office,’’ by Pieter Brueghel the Younger (1640)

Via OtherWords.org

BOSTON

Want to know where the 2020 presidential election is heading? Don’t obsess about the polls. Pay attention to tax lawyers and accountants.

These experts in reducing rich people’s tax bills understand what many Americans still haven’t quite fathomed: The nation’s wealthiest will likely pay significantly more in taxes if Joe Biden becomes president.

Why? Because the massive tax cuts for corporations and the rich that Trump and the GOP passed in 2017 may soon be shredded.

If these rich don’t take immediate steps to “protect their fortunes,” their law firms are advising, they could lose out big-time. “We’ve been telling people: ‘Use it or lose it,’” says Jere Doyle, a strategist at BNY Mellon Wealth Management.

At first, these concerns may appear overblown. Under Biden’s plan, the tax rate on America’s top income tax bracket would only rise from 37 percent back up to 39.6 percent, the Obama-era rate.

But the real “backbreakers” for the rich come elsewhere.

Among the biggest: a new tax treatment for “investment income,” the money that rich people make buying and selling assets.

Most of this income currently enjoys a super-discounted tax rate — just 20 percent, far lower than what most working people pay on their paycheck income. The Biden tax plan ends this favorable treatment of income from “capital gains” for taxpayers making over $1 million. It would also close the loophole where wealthy people simply pass appreciated assets to their heirs.

Biden is also proposing an overhaul of Social Security taxes. The current 12.4 percent Social Security payroll tax — half paid by employers, half by employees — applies this year to only the first $137,700 in paycheck earnings, a figure that gets annually adjusted to inflation.

That means that a corporate exec who makes $1 million this year will pay the same amount into Social Security as a person who makes $137,700.

Biden’s plan would apply the Social Security tax to all paycheck income over $400,000, so America’s deepest pockets would pay substantially more to support Social Security. Meanwhile Americans making under $400,000 would continue to pay at current levels.

Corporations would also pay more in taxes. Biden would raise the standard corporate income tax rate from 21 to 28 percent, set a 15 percent minimum tax on corporate profits, and double the current minimum tax foreign subsidiaries of U.S. companies have to pay from 10.5 to 21 percent.

Among other changes: Big Pharma companies would no longer get tax deductions for what they spend on advertising. Real estate moguls would no longer be able to depreciate the rental housing they own on an accelerated schedule, and fossil-fuel companies would lose a variety of lucrative tax preferences.

Together, these ideas could measurably reduce inequality.

The Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy has crunched the numbers: In 2022, under Biden’s plan, the nation’s top 1 percent would bear 97 percent of the direct tax increases Biden is proposing. The next most affluent 4 percent would bear the remaining 3 percent.

Despite some misleading Republican talking points to the contrary, no households making under $400,000 — the vast majority of Americans — would see their direct taxes rise.

Even if Democrats win the Senate, actually passing this plan will take grassroots pressure — the only force that has ever significantly raised taxes on the rich.

Wealth inequality remains an even greater challenge, and the Biden plan includes no wealth tax along the lines of what Senators Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, two of Biden’s primary rivals, advocated. But more pressure could also shove that wealth tax onto the table.

If that happens, we might finally begin to reverse the staggering levels of inequality that Ronald Reagan’s 1980 election ushered in.

Sam Pizzigati, based in Boston, is the co-editor of Inequality.org and author of The Case for a Maximum Wage and The Rich Don’t Always Win.

Sam Pizzigati: How taxpayers funded 'consulting fees' for Ivanka Trump

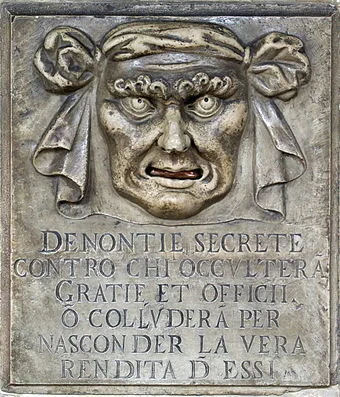

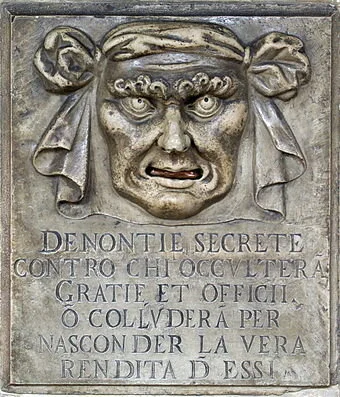

A "Lion's Mouth" postbox for anonymous denunciations at the Doge's Palace, in Venice. Translation: "Secret denunciations against anyone who will conceal favors and services or will collude to hide the true revenue from them."

Via OtherWords. org

BOSTON

The warmest and fuzziest phrase in the political folklore of American capitalism? “Family-owned business”!

These few words evoke everything people like and admire about the U.S. economy. The always welcoming luncheonette. The barbershop where you can still get a haircut, with a generous tip, for less than $20. The corner candy store.

But “family-owned businesses” have a dark side, too, as we see all too clearly in the Trump Organization. We now know — thanks to the recent landmark New York Times exposé on Trump’s taxes — far more about this sordid empire than ever before.

Put simply, the report shows how great wealth gives wealthy families the power to get away with greed grabs that would plunge more modest families into the deepest of hot water.

Let’s imagine, for a moment, a family that runs a popular neighborhood pizza parlor. Melting mozzarella clears this family-owned business $100,000 a year. The family owes and pays federal income taxes on all this income.

Now let’s suppose that they had a conniving neighbor who one day suggested that he knew how the family could easily cut its annual tax bill by thousands.

All the family needed to do: hire its teenage daughter as a “consultant” — at $20,000 a year — and then deduct that “consulting fee” as a business expense. That move would sink the family’s taxable income yet keep all its real income in the family.

The ma and pa of this local pizza palace listen to all this, absolutely horrified. Their daughter, they point out, knows nothing about making pizzas. How could she be a consultant? Pretending she was, ma and pa scolded, would be committing tax fraud.

The chastened neighbor slinks away.

Donald Trump goes by a different standard. Between 2010 and 2018, Trump’s hotel projects around the world cleared an income of well over $100 million. On his tax returns, Trump claimed $26 million in “consulting” expenses, about 20 percent of all the income he made on these hotel deals.

Who received all these “consulting” dollars? Trump’s tax returns don’t say. But New York Times reporters found that Ivanka Trump had collected consulting fees for $747,622 — the exact sum her father’s tax return claimed as a consultant-fee tax deduction for hotel projects in Vancouver and Hawaii.

All the $26.2 million in Trump hotel project consulting fees, a CNN analysis points out, may well have gone to Ivanka or her siblings.

More evidence of the Trump consulting hanky-panky: People with direct involvement in the various hotel projects where big bucks went for consulting, The Times notes, “expressed bafflement when asked about consultants on the project.” They told the paper that they never interacted with any consultants.

The New York Times determination: “Trump reduced his taxable income by treating a family member as a consultant and then deducting the fee as a cost of doing business.”

During the 2016 presidential debates, Donald Trump dubbed his aggressive tax-reducing moves as “smart.” Now, veteran tax analysts have a different label: criminal. Daniel Shaviro, a tax law prof at New York University, feels that “several different types of fraud may have been involved here.”

Ivanka Trump, adds former Watergate prosecutor Nick Akerman, had no “legitimate reason” to collect consulting fees for the Trump hotel projects “since she was being paid already as a Trump employee.” Donald and Ivanka Trump, says Akerman, should with “no question” be facing “at least five years in prison for tax evasion.”

Plutocrats don’t play by the same rules as pizza parlors, and that won’t change so long as Donald Trump remains in the White House. But these new revelations may make that a harder sell.

Sam Pizzigati, based in Boston, co-edits Inequality.org for the Institute for Policy Studies. He’s the author of The Case for a Maximum Wage and The Rich Don’t Always Win. This op-ed was adapted from Inequality.org and distributed by OtherWords.org.

Sam Pizzigati: Bloomberg could buy 2020 election and still make money

Via OtherWords.org

BOSTON

Gracie Mansion, the official residence of New York’s mayors since 1942, hosted billionaire Michael Bloomberg for three terms.

The first of these terms began after Bloomberg, then the Republican candidate for mayor, spent an incredible $74 million to get himself elected in 2001. He spent, in effect, $99 for every vote he received.

Four years later, Bloomberg — who made his fortune selling high-tech information systems to Wall Street — had to spend even more to get himself re-elected. His 2005 campaign bill came to $85 million, about $112 per vote.

In 2009, he had the toughest sledding yet. Bloomberg first had to maneuver his way around term limits, then persuade a distinctly unenthusiastic electorate to give him a majority. Against a lackluster Democratic Party candidate, Bloomberg won that majority — but just barely, with 51 percent of the vote.

That majority cost Bloomberg $102 million, or $174 a vote.

Now Bloomberg has announced he’s running for president as a Democrat, arguing he has the best chance of unseating President Trump, whom he describes as an “existential threat.” Could he replicate his lavish New York City campaign spending at the national level? Could he possibly afford to shell $174 a vote nationwide — or even just $99 a vote?

Let’s do the math. Donald Trump won the White House with just under 63 million votes. We can safely assume that Bloomberg would need at least that 63 million. At $100 a vote, a victory in November 2020 would run Bloomberg $6.3 billion.

Bloomberg is currently sitting on a personal fortune worth $52 billion. He could easily afford to invest $6.3 billion in a presidential campaign — or even less on a primary.

Indeed, $6.3 billion might even rate as a fairly sensible business investment. Several of the other presidential candidates are calling for various forms of wealth taxes. If the most rigorous of these were enacted, Bloomberg’s grand fortune would shrink substantially — by more than $3 billion next year, according to one estimate.

In other words, by undercutting wealth-tax advocates, Bloomberg would save over $6 billion in taxes in just two years — enough to cover the cost of a $6.3 billion presidential campaign, give or take a couple hundred million.

Bloomberg, remember, wouldn’t have to win the White House to stop a wealth tax. He would just need to run a campaign that successfully paints such a tax as a clear and present danger to prosperity, a claim he has already started making.

Bloomberg wouldn’t even need to spend $6.3 billion to get that deed done. Earlier this year, one of Bloomberg’s top advisers opined that $500 million could take his candidate through the first few months of the primary season.

How would that $500 million compare to the campaign war chests of the two primary candidacies Bloomberg fears most? Bernie Sanders raised $25.3 million in 2019’s third quarter for his campaign, Elizabeth Warren $24.6 million. Both candidates are collecting donations — from small donors — at a $100 million annual pace.

Bloomberg could spend 10 times that amount on a presidential campaign and still, given his normal annual income, end the year worth several billion more than when the year started.

Most Americans don’t yet believe that billionaires shouldn’t exist. But most Americans do believe that America’s super rich shouldn’t be able to buy elections or horribly distort their outcomes.

But unfortunately, they can — or at least, you can be sure they’ll try.

Sam Pizzigati, based in Boston, co-edits Inequality.org for the Institute for Policy Studies. His recent books include The Case for a Maximum Wage and The Rich Don’t Always Win.

Sam Pizzigati: How much 'inequality tax' are you paying?

In the Swiss Alps

From OtherWords.org

BOSTON

What’s the richest country?

That may seem like a simple question, but it’s not. According to the Global Wealth Report from banking giant Credit Suisse, it all depends on how we define “richest.”

If we mean the nation with the most total wealth, we have a clear No. 1: the United States. The 245 million U.S. adults hold a combined net worth of $106 trillion.

No other nation comes close. China ranks a distant second, with a mere $64 trillion, Japan even further back at $25 trillion.

But if we mean the nation with the most wealth per person, top billing goes to Switzerland. The average Swiss adult is sitting on a $565,000 personal nest-egg. Americans average $432,000, only good enough for second place.

So does Switzerland merit the title of the world’s wealthiest nation? Not necessarily.

The Swiss may sport the world’s highest average wealth, but that doesn’t automatically mean that their nation has the world’s richest average people.

We’re not playing word games here. We’re talking about the important distinction that statisticians draw between mean and median.

To calculate a national wealth mean — a simple average — researchers just divide total wealth by number of people. The problem? If some people have fantastically more wealth than other people, the resulting average will give a misleading picture about economic life as average people live it.

Medians can paint a more realistic picture. Statisticians calculate the median wealth of a nation by identifying the midpoint in the nation’s wealth distribution — that point at which half the nation’s population has more wealth and half less.

Medians, in other words, can tell us how much wealth ordinary people hold.

By this median measure, Switzerland holds up as a strikingly wealthy nation. The United States does not. Typical Swiss adults turn out to hold $228,000 in net worth, the most in the world. Typical Americans hold personal fortunes worth just $66,000.

Typical Canadians, with $107,000 per adult, have more wealth than that U.S. total. So do typical Taiwanese ($70,000), typical Brits ($97,000), and typical Australians ($181,000).

Overall, typical adults in 16 other developed nations have more wealth than we do here. Typical Japanese adults, for instance, hold $110,000 in personal wealth, a net worth considerably higher than the $66,000 Americans can claim.

Why do ordinary Americans have so little wealth when they live in a nation that has so much? In a word: inequality. Other nations have much more equal distributions of income and wealth than the United States.

Japan in particular stands out here. The new Credit Suisse 2019 Global Wealth Report notes that Japan “has a more equal wealth distribution than any other major country.” Japan’s richest 10 percent holds less than half their nation’s wealth, just 48 percent. In the United States, the top 10 percent hold nearly 76 percent, over three-quarters of national wealth.

How would typical Americans fare if we were as equal as Japan? If we succeeded at turning our economy around that way, the net worth of America’s most typical adults would triple, from $66,000 to $199,000.

In effect, the difference between those two totals amounts to an “inequality tax.”

By letting our rich grab an oversized share of the wealth all of us help create, we are taxing ourselves into economic insecurity. Other nations don’t tolerate greed grabs. Why should we?

Sam Pizzigati, based in Boston, co-edits Inequality.org for the Institute for Policy Studies. His latest book is The Case for a Maximum Wage.

HOW MUCH ‘INEQUALITY TAX’ ARE YOU PAYING?

If the U.S. were as equal as Japan, the average American’s wealth would triple. Inequality is like a tax on two-thirds of your income.

By Sam Pizzigati | October 29, 2019

Who is the world’s richest country?

That may seem like a simple question, but it’s not. According to the Global Wealth Report from banking giant Credit Suisse, it all depends on how we define “richest.”

If we mean the nation with the most total wealth, we have a clear No. 1: the United States. The 245 million U.S. adults hold a combined net worth of $106 trillion.

No other nation comes close. China ranks a distant second, with a mere $64 trillion, Japan even further back at $25 trillion.

But if we mean the nation with the most wealth per person, top billing goes to Switzerland. The average Swiss adult is sitting on a $565,000 personal nest-egg. Americans average $432,000, only good enough for second place.

So does Switzerland merit the title of the world’s wealthiest nation? Not necessarily.

The Swiss may sport the world’s highest average wealth, but that doesn’t automatically mean that their nation has the world’s richest average people.

We’re not playing word games here. We’re talking about the important distinction that statisticians draw between mean and median.

To calculate a national wealth mean — a simple average — researchers just divide total wealth by number of people. The problem? If some people have fantastically more wealth than other people, the resulting average will give a misleading picture about economic life as average people live it.

Medians can paint a more realistic picture. Statisticians calculate the median wealth of a nation by identifying the midpoint in the nation’s wealth distribution — that point at which half the nation’s population has more wealth and half less.

Medians, in other words, can tell us how much wealth ordinary people hold.

By this median measure, Switzerland holds up as a strikingly wealthy nation. The United States does not. Typical Swiss adults turn out to hold $228,000 in net worth, the most in the world. Typical Americans hold personal fortunes worth just $66,000.

Typical Canadians, with $107,000 per adult, have more wealth than that U.S. total. So do typical Taiwanese ($70,000), typical Brits ($97,000), and typical Australians ($181,000).

Overall, typical adults in 16 other developed nations have more wealth than we do here. Typical Japanese adults, for instance, hold $110,000 in personal wealth, a net worth considerably higher than the $66,000 Americans can claim.

Why do ordinary Americans have so little wealth when they live in a nation that has so much? In a word: inequality. Other nations have much more equal distributions of income and wealth than the United States.

Japan in particular stands out here. The new Credit Suisse 2019 Global Wealth Report notes that Japan “has a more equal wealth distribution than any other major country.” Japan’s richest 10 percent holds less than half their nation’s wealth, just 48 percent. In the United States, the top 10 percent hold nearly 76 percent, over three-quarters of national wealth.

How would typical Americans fare if we were as equal as Japan? If we succeeded at turning our economy around that way, the net worth of America’s most typical adults would triple, from $66,000 to $199,000.

In effect, the difference between those two totals amounts to an “inequality tax.”

By letting our rich grab an oversized share of the wealth all of us help create, we are taxing ourselves into economic insecurity. Other nations don’t tolerate greed grabs. Why should we?

Related Posts:

OtherWords commentaries are free to re-publish in print and online — all it takes is a simple attribution to OtherWords.org. To get a roundup of our work each Wednesday, sign up for our free weekly newsletter here.

Sam Pizzigati co-edits Inequality.org for the Institute for Policy Studies. His latest book is The Case for a Maximum Wage. This op-ed was distributed by OtherWords.org.

Sam Pizzigati: Class war hits the water

Via OtherWords.org

We typically think of urban neighborhoods when we think of gentrification — places where modest-income families thrived for generations suddenly becoming no-go zones for all but the affluent.

The waters around us have always seemed a place of escape from all this displacement, a more democratic space where the rich can stake no claim. The wealthy, after all, can’t displace someone fishing on a lake or sailing off the coast.

Or can they? People who work and play around our waters are starting to worry.

Local boat dealers and fishing aficionados alike, a leading marine industry trade journal reports, have begun “expressing concern about the growing income disparity in the United States.”

What has boat dealers so concerned? The middle-class families they’ve counted on for decades are feeling too squeezed to buy their boats — or even continue boating.

“Boating has now priced out the middle-class buyer,” one retailer opined to a Soundings Trade Only survey. “Only the near rich/very rich can boat.”

Mark Jeffreys, a high school finance teacher who hosts a popular bass fishing webcast, worries that his pastime is getting too pricey — and wonders when bass anglers just aren’t going to pay “$9 for a crankbait.”

Not everyone around water is worrying. The companies that build boats, Jeffreys notes, seem to “have been able to do very well.” They’re making fewer boats but clearing “a tremendous amount” on the boats they do make.

In effect, the marine industry is experiencing the same market dynamics that sooner or later distort every sector of an economy that’s growing wildly more unequal. The more wealth tilts toward the top, research shows, the more companies tilt their businesses to serving that top.

In relatively equal societies, Columbia University’s Moshe Adler points out, companies have “little to gain from selling only to the rich.” But that all changes when wealth begins to concentrate. Businesses can suddenly charge more for their wares — and not worry if the less affluent can’t afford the freight.

The rich, to be sure, don’t yet totally rule the waves. But they appear to be busily fortifying those stretches of the seas where they park their vessels, as Forbes has just detailed in a look at the latest in superyacht security.

Deep pockets have realized that people of modest means may not take well to people of ample means — “cocktails in hand” — floating “massive amounts of wealth” into their harbors. In 2019’s first quarter alone, the International Maritime Bureau reports, unwelcome guests boarded some 27 vessels and shot up seven.

Anxious yacht owners, in response, are outfitting their boats with high-tech military-style hardware.

One new “non-lethal anti-piracy device” emits pain-inducing sound beams. Should that sound fail to dissuade, the yachting crowd can turn on a “cloak system” from Global Ocean Security Technologies. The “GOST cloak” can fill the area surrounding any yacht with an “impenetrable cloud of smoke” that “reduces visibility to less than one foot.”

The resulting confusion, the theory goes, will give nearby authorities the time they need to come to a besieged yacht’s rescue.

But who will rescue the boating middle class? Maybe we need an “anti-cloak,” a device that can blow away all the obfuscations the rich pump into our national political discourse, the mystifications that blind us to the snarly impact of grand concentrations of private wealth on land and sea.

Or maybe we just need to roll up our sleeves and organize for a more equal future.

Sam Pizzigati co-edits Inequality.org for the Institute for Policy Studies. His latest book is The Case for a Maximum Wage.

Sam Pizzigati: Economic Inequality helps launch helicopter parents

Anxious parents taking the family house to their kids college?

Via OtherWords.org