Pinnacle of puppetry

”Turkey Gobbler Balloon, Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade, 1929,’’ by German-American artist Tony Sarg (1880-1942), in the show “Tony Sarg: Genius at Play,’’ at the Norman Rockwell Museum, Stockbridge, Mass., through Nov. 5

— Photographer unknown, from the collection of the Nantucket Historical Association

The museum says:

The show “is the first comprehensive exhibition exploring the life, art and adventures of Tony Sarg, the charismatic illustrator, animator, puppeteer, designer, entrepreneur and showman who is celebrated as the father of modern puppetry in North America. His vast knowledge of puppet technology was instrumental in his design of the inaugural Thanksgiving Day parade balloon for Macy’s Department Store, in 1927, as well as subsequent parade balloons and automated displays for the company’s festive holiday windows, which were imitated nationwide. The creator of a host of popular consumer goods, from toys and clothing to home décor, Sarg also envisioned fanciful illustrated maps and created mural designs for the Oasis Cafe in New York’s Waldorf Astoria Hotel.’’

Sarg's “Nantucket Sea Serpent,’’ 1937.

— From the Nantucket Historical Association

The famed Austen Riggs Center, in Stockbridge, a mental hospital known for, among things, very quietly treating celebrities.

— Photo by Joe Mabel

Self-defense training

“Lando as a Boy” (oil on board), by Alexander Bostic, at the Norman Rockwell Museum, Stockbridge, Mass.

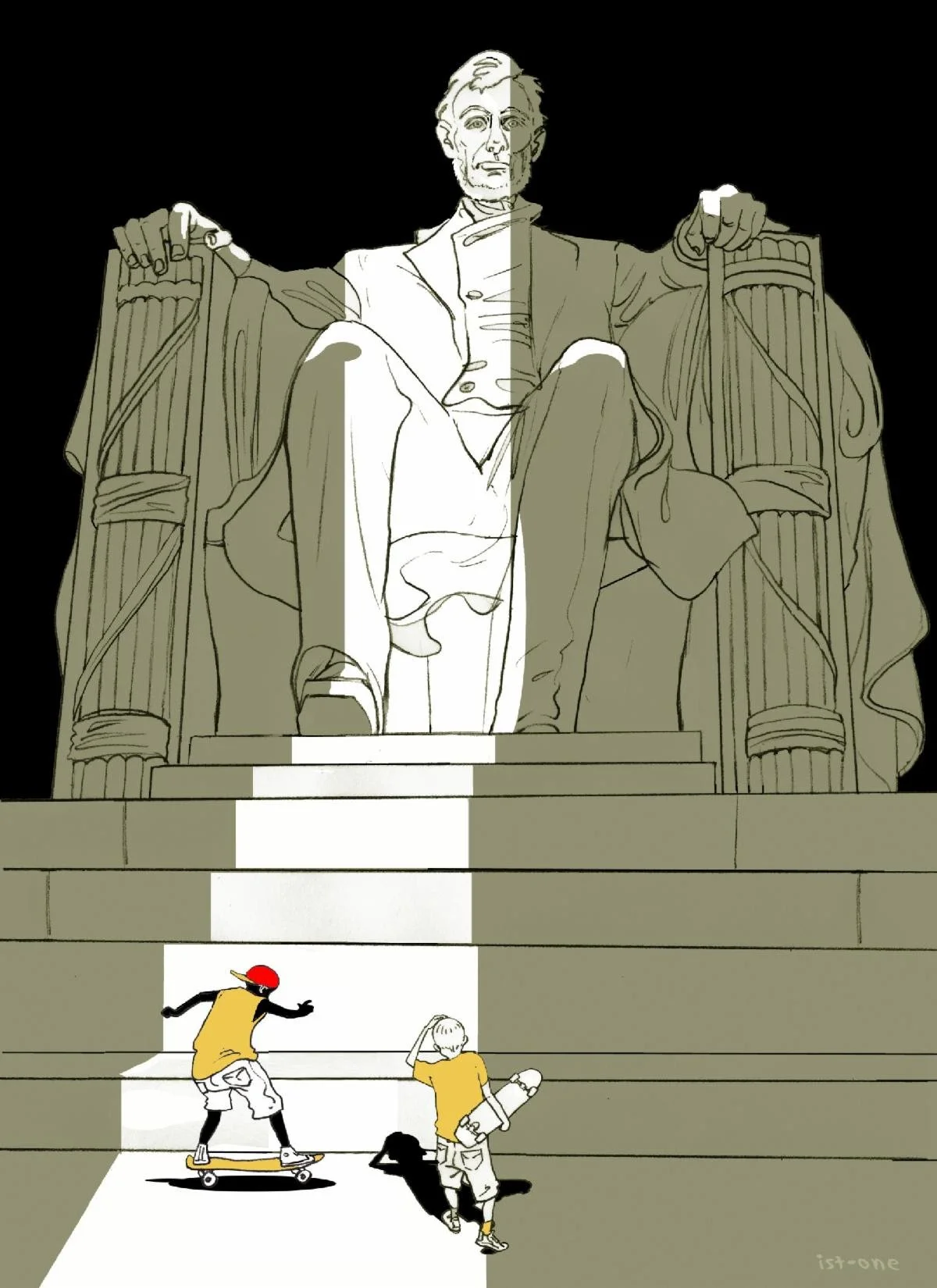

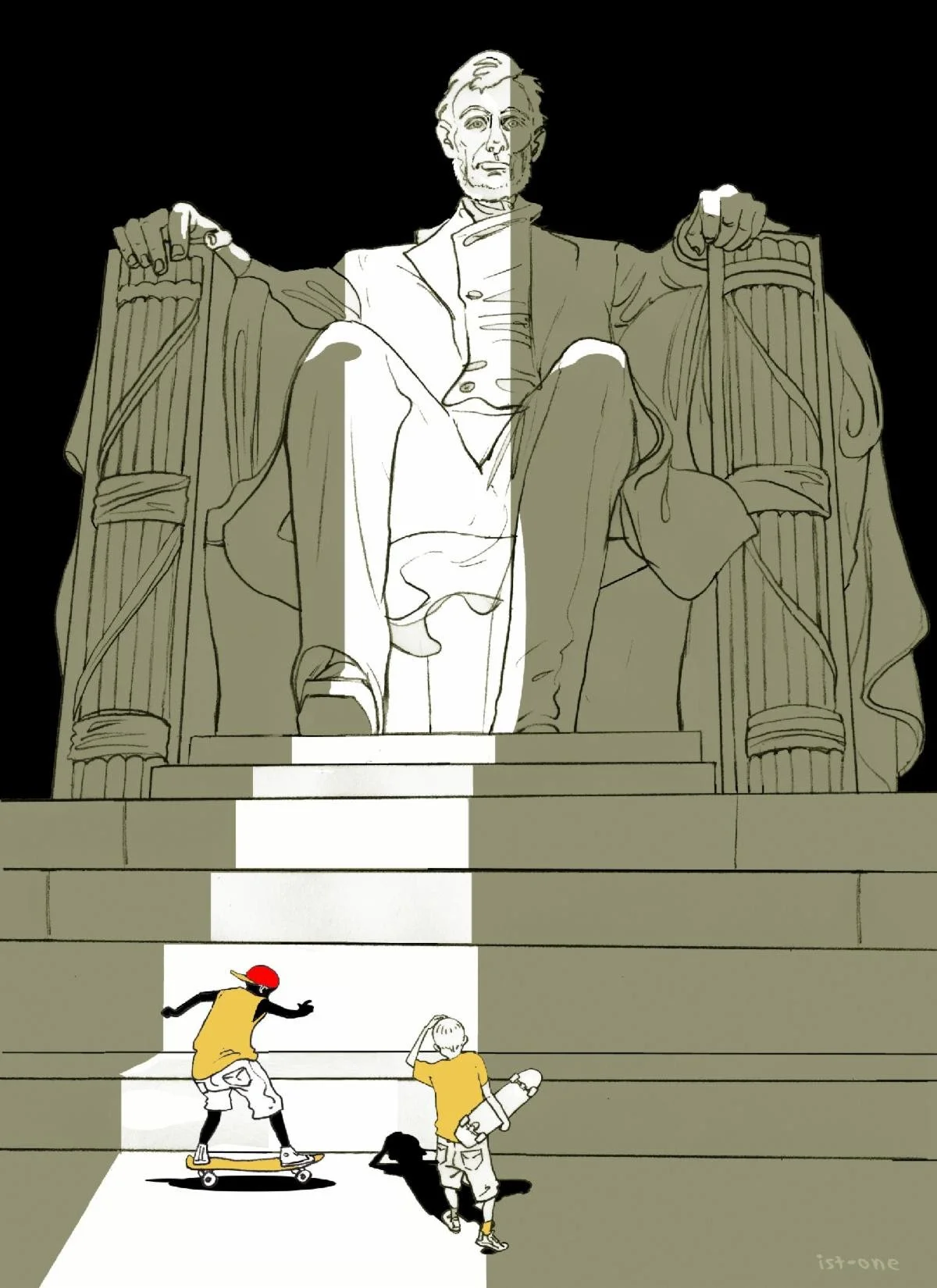

The art around our greatest president

Istvan Banyai, “Set in Stone” (cover illustration of The New Yorker, digital), by Istvan Banyai, in the exhibition “The Lincoln Memorial Illustrated,’’ at the Norman Rockwell Museum, Stockbridge, Mass., May 7-Sept. 4, in collaboration with Chesterwood.

The museum says: “Approximately fifty historical and contemporary artworks by noted illustrators and cartoonists will be featured, as will archival photographs, sculptural elements, artifacts and ephemera.” For more information, please visit nrm.org.

Studio and garden at Chesterwood

Photos by I, Daderot

Chesterwood was the summer estate and studio of American sculptor Daniel Chester French (1850–1931), in Stockbridge. French created the brooding-looking sculpture of Abraham Lincoln for the Lincoln Memorial. Most of French's originally 150-acre estate is now owned by the National Trust for Historic Preservation, which operates the property as a museum and sculpture garden. The property was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1965 in recognition of French's importance in American sculpture.

Inside French’s studio

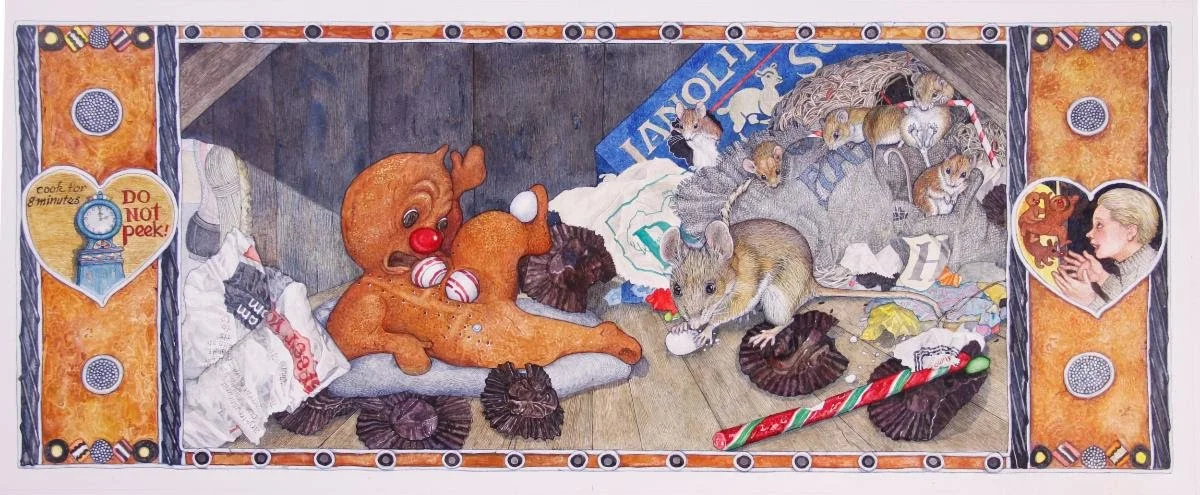

Call pest control?And treating Norman Rockwell

“Scritchy Scratchy,” by Jan Brett (watercolor on paper, illustration for Gingerbread Friends), in the show “Jan Brett: Stories Near and Far,’’ at the Norman Rockwell Museum, Stockbridge, Mass., through March 6.

Ms. Brett is the author/illustrator of such books for kids as The Mitten, Cozy and Gingerbread Baby. She has homes in the Berkshires and in Norwell, Mass., where she grew up.

The North River, with beautiful marshes, forms the southeast boundary of Norwell.

The famous Austen Riggs Center, a psychiatric institution in Stockbridge, the Berkshires town that the famed painter and illustrator Norman Rockwell (1894-1978) moved to at least in part because of Riggs, where he and his second wife, Mary Barstow, were both treated for mental illness. His wife, the more seriously ill of the two, suffered from depression and alcoholism and Rockwell from depression and anxiety.

The very expensive Riggs had the reputation of drawing well-known patients and celebrated psychiatrists.

Rockwell once said: "I paint life as I would like it to be.’’

Police brutality

“Expired Meter’’ (oil on board) by George Hughes (1907-1990), at the National Museum of American Illustration, Newport

(c) 2020 National Museum of American Illustration, Newport, RI, and the American Illustrators Gallery, New York, NY

Mr. Hughes lived for the last part of his life in Arlington. Vt., between the Taconic Range and the southern Green Mountains, where one of his neighbors for some years was the far more famous illustrator Norman Rockwell, who eventually moved to Stockbridge, Mass., in the Berkshires.

Fog over the Battenkill River in West Arlington, Vt.

An old inn, Rockwell, a mental hospital and Arlo

The Red Lion inn (first part built in 1773), in Stockbridge.

“And in the quiet, rural middle of it {the Berkshires}, Stockbridge sits like nothing so much as a living postcard from small town America. Standing at dusk on Main Street, looking at the row of seasoned old storefronts, the long, classic porch of the fabled Red Lion Inn wrapping around the corner, and the tree-studded ridgeline of the Berkshires creating a green and gold and backdrop to it all, a visitor might be put in mind of a Norman Rockwell painting. Which would be perfectly apt. Rockwell lived only a block away, and he painted that very scene.’’

-- From New England Notebook, by Ted Reinsteim

He might also have noted that Stockbridge is also home to the Austen Riggs Center, a psychiatric hospital known for its celebrity patients. Its presence was a factor in Rockwell and his wife moving to the town from Arlington, Vt. Mr. and Mrs. Rockwell were both treated there for anxiety and depression. Stockbridge also hosts the Norman Rockwell Museum, which has many of the famous illustrations he did for the old Saturday Evening Post and other publications in the Golden Age of Magazines.

His Stockbridge studio was on the second floor of a row of buildings; directly underneath Rockwell's studio was, for a time in 1966, the Back Room Rest, better known as the famous "Alice's Restaurant of song and movie fame, about a bunch of '60s Hippies led (sort of!) by songwriter Arlo Guthrie and their interactions with small-town life.

The Norman Rockwell Museum.

Colorized postcard of Stockbridge made in the early 20th Century.

The way he wanted life to look

Norman Rockwell (1894-1978), “The Bridge Game,” 1948, oil on canvas, published by Saturday Evening Post, May 15, 1948 cover Image Courtesy of National Museum of American Illustration, Newport, RI., cover image © SEPS: www.curtispublishing.com.

There’s another picture below.(Rerunning this posting from the pre-renovation version of New England Diary a few weeks ago.)

The New York Times seems to be on a Norman Rockwell kick, with a long review of a new book out about him and a travel piece about Arlington, Vt., where he lived for a long time.

That was before he moved to Stockbridge, Mass, in the Berkshires, to, among other things, be closer to Austen Riggs, the mental hospital identified with many celebrity patients.

As Deborah Solomon (who also wrote the travel story) writes in “American Mirror: The Art and Life of Norman Rockwell,” his life was far more complex and darker than most of his beautiful art. That he was a troubled man (who ain’t?) is not news, but Ms. Solomon puts it together very well indeed.

He was apparently conflicted about homosexual longings, had three troubled marriages and was a lifelong hypochondriac. The Thoreau line about “the mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation” comes to mind. Still, he obviously found much comfort and joy in his studio. Do too many writers these days make too much of sexual conflicts? Maybe a highly creative person’s biggest trauma is the difficulty of finding meaning in a seemingly chaotic world, a torturous search for ultimate meaning.

Some of this reminds me of the strange story of Robert Frost, whose public image as a sort of quaint, folksy, friendly rural poet was so false. In fact, Frost, a kind of Modernist, used his New England settings to explore existential quandaries; and he could be a very nasty man.

Many of his poems were dark, dark, dark. Take a look at his poem design “Design”.

But, in part because his folksy image got him many lucrative lecture gigs, he played along with it, to a point (while winking).

But then, behind almost family’s door is conflict and mental illness of varying seriousness. In some way, maybe imaginative repression and diversion, Rockwell got great popular art done despite, or because of, his problems, through vast technical skill, knowledge of other masters’ work and a rich visual imagination.

The Rockwell renaissance also reminds me of how much many of us miss the golden age of magazines, such as The Saturday Evening Post, for which Rockwell did so much work. The weekly arrival of pubs such as The Post and Life magazine was a joy that I, anyway, have never found with TV, the Internet and newspapers (with the possible exception of the beautiful old New York Herald Tribune).

That is probably ungrateful, since newspapers paid for most of my upkeep for almost 44 years.

Speaking of the past, I was pleasantly surprised to see that John Wilmerding, my art-history professor of almost a half century ago at Dartmouth, was the reviewer of Ms. Solomon’s fine new book. Mr, Wilmerding, an heir to great Havemeyer sugar fortune in New York, also has one of America’s greatest collections of American art, much of which he is giving away.

The best places to see Rockwell work are the National Museum of American Illustration, in Newport, and, the Norman Rockwell Museum, in Stockbridge.

Norman Rockwell (1894-1978), ”Volunteer Fireman,” 1931, oil on canvas, published by Saturday Evening Post, March 28, 1931 cover image Courtesy of National Museum of American Illustration, Newport, RI. Saturday Evening Post cover image © SEPS: www.curtispublishing.com