Stuart Vyse: Looking for the light in our inner worlds

This essay first ran in New England Diary on Nov. 19, 2017

I used to dread the descent into darkness in late autumn. There comes a time when, well before you get up from your desk to go home, the world outside your window is as black as midnight. It is barely five o'clock in the afternoon, but there is no natural light left to guide you home or illuminate your evening activities. It is too early to sleep, and yet you must push against the blackness to stay alert and awake. Eventually here in the northern latitudes, the reluctant cold-weather sun manages only the briefest appearance in the middle of the day before slipping away behind a mid-afternoon sunset.

It is easy to feel depressed by the weight of light's absence -- by a life that sometimes feels subterranean and nightmarish. But I have come to welcome the change of year. Seasons mark the time. All seasons. They tell us we have been here before, and if all goes well, we will be here again. The changing light and landscape conjure memories: of jumping in piles of leaves, of a beautiful ice storm, or of a frozen lemonade drunk in the car on the way home from the beach.

Thanks to a quirk of our psychology, we tend to suppress the unpleasantness of the past, and our memories are often warm and nostalgic, no matter what the temperament of those distant times.

I have grown to appreciate the brightness hidden within the winter black. There are the familiar holidays clustered around winter solstice -- that shortest day when the darkness begins to slowly pull back its veil. These celebrations are filled with candles and lights and burning fires that show the way to the equinox and warm weather beyond.

Although there is less light around the solstice, the light there is is of a special quality. The winter sun hurls its shafts through the window at a flatter angle, crashing them against the floors and walls. During the season we are inside the most, the sun finds a way to light the room as brilliantly as possible, and then too soon it is gone.

But, for me, the great hidden light of the dark season can only be seen from outside. As you walk the sidewalks or drive through your neighborhood at night, the houses are lit from inside out, throwing great yellow beams onto the lawn. We never know what goes on in other people's homes, and sometimes it is better that way. But from a safe distance away I imagine families together -- not avoiding the darkness outside, but drawn to the light and heat inside. Making a warm world together within the wintry one beyond the walls.

Perhaps it is wishful thinking, but I like to imagine that, for those of us who live where there are seasons, this cycle serves an important purpose. I want to believe that during this time of year when the sun recedes beyond the horizon, nature compels us to go home. Like bears returning to their caves, we come inside -- not to hibernate -- but to awaken to a different source of illumination.

The spinning Earth tells us to spend a little less time outside and a little more with family and friends -- and, perhaps, a little more in the smaller spaces of our inner worlds. Ideally, when the warm weather returns, we emerge restored, with a new appreciation of the world outside.

Of course, life is not always ideal. Sometimes the sense of cold-weather fellowship is more an idea -- a memory -- than a reality. Easier seen from outside on the sidewalk than from inside the house. But even then, the blackness of winter provides the perfect backdrop for imagination and reexamination. As we are forced indoors we have a chance to look inward, too. A chance to seek a private incandescence to guide us through the dark season.

Perhaps this is part of what the winter holidays are supposed to do. Show us a different source of light; encourage us to look inward as we go inside; and give us hope that the spring will come again.

The gathering shadows of autumn are often difficult to accept. The hope of longer days seems so far away. But I have come to understand that, when darkness comes, we need not rue the absent sun. It is simply time to go inside and make our own light.

Stuart Vyse is a psychologist and writer living in Stonington, Conn., where he lives in the old Steamboat Hotel, about which he wrote an eponymous book.

The publisher explains:

“From 1837 to 1900, the tiny borough of Stonington, Connecticut, was a major transportation hub on the route between New York and Boston. Steamboats leaving Manhattan followed Long Island Sound to Stonington Harbor, where passengers boarded trains for the rest of the journey to Providence or Boston. Stonington’s Steamboat Hotel, built 1838 near the piers and railroad yard, was home to saloons, restaurants, a pool hall, a cigar shop, a tailor and a barber shop. Merchants, hotel keepers and saloon workers passed through the building, each with their own unique story. Many of them were immigrants or first-generation Americans, and they are a window on a late nineteenth-century class of merchants and service workers. Join local author Stuart Vyse as he reveals a lively portrait of remarkable harmony in a small village that was far more diverse than it is today.’’

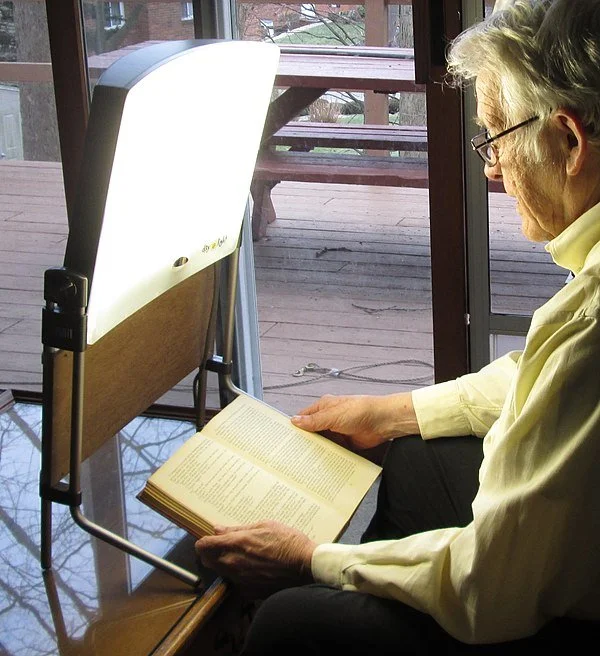

Bright light therapy is a common treatment for seasonal affective disorder, which is associated with diminished sunlight from fall into the winter.

Where will the coastal year-rounders live?

Stonington waterfront in1915

Aerial view of fancy summer resort town Camden, Maine, from the harbor

—Photo by King of Hearts

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

‘Many coastal communities in New England face severe housing shortages for year-round residents of modest means. Around here, Nantucket, Martha’s Vineyard and Block Island are infamous for this problem.

Consider Stonington, Maine, on Deer Isle. There, 80 percent of its shorefront is now owned by non-residents (mostly summer people), as are 56 percent of that fishing (mostly lobsters) port’s downtown properties, according to a report in the Portland Press Herald

The usually affluent summer folks bid up real estate prices to levels unaffordable to most year-rounders.

So where will the carpenters, yard-work people, plumbers, electricians and schoolteachers live? Perhaps some elderly summer people will leave their summer McMansions to towns to be converted into affordable housing. Just joking. But something must be done if these towns are going to have enough of the locals who make communities viable for year-round and summer people. That includes zoning changes and/or having states subsidize the construction of new housing in some places.

Death village

Water Street in Stonington, Conn.

“Shortly before I died,

Or possibly after,

I moved to a small village by the sea….

The rocky sliver of land, the little houses where the fishermen once lived.…”

— From “In the Village,’’ by James Longenbach (1959-2022), America poet. The poem is inspired by his time in Stonington, Conn.

Don Pesci: Conn.’s temporary gasoline-tax cut and trying to repeal economic common sense

Major roads of Connecticut

VERNON, Conn.

The default position of Connecticut’s majority Democrats on the matter of getting and spending has not changed within the past three decades: Tax cuts, infrequently imposed, should be temporary and bravely endured, while tax increases, deployed for the most part to satisfy imperious state-employee-union demands, should be permanent.

The recent temporary suspension of Connecticut’s 25-cent-a-gallon excise gasoline tax conforms to the default position of Democrats who have controlled Connecticut’s General Assembly for the last 30 years: The tax is to be suspended – operative word – “temporarily” from April to July 1.

Connecticut Democrats, it should seem obvious, are reading from a national Democratic script.

The increase in the price of gasoline, they say, is due chiefly to the Russian war of aggression in Ukraine and the greedy oil barons.

The debate in the General Assembly on reducing Connecticut’s gasoline tax centered upon whether the reduction should be temporary or permanent.

“Rep. Sean Scanlon, a Guilford Democrat who co-chairs the tax-writing committee,” one newspaper noted, “said many constituents have been hurting from the rising prices at the pump, which was recently an average of $4.32 a gallon.

“Our constituents did not start a war in Ukraine,’' Scanlon argued. “Our constituents did not contribute to the global supply chain. ... This is a great first step that we can make to give them some affordability, some relief. ... At least we’re doing something.”

The newspaper correctly noted, “The tax cuts are possible partly because the state has large budget surpluses in two separate funds due to increased federal stimulus money and capital gains taxes from Wall Street increases, paid largely by millionaires and billionaires in Fairfield County.”

In the state Senate chamber, also dominated by Democrats, Will Haskell, of Westport, rose to the occasion. Haskell argued that the gasoline-tax cut should not be permanent because providing permanent relief would deliver a “debilitating blow’' to the state’s plans to spend millions of dollars to fix roads and bridges. The paper quoted Haskell: “Gas prices are high, but not because of taxes. It’s because of [Russian dictator Vladimir] Putin.”

The federal government – which prints money, borrows money and acquires money through excessive taxation – is flush with funds now being distributed by the Biden administration to various political receptacles, some say for political purposes. In many instances, states are using the funds to offset business slowdowns caused by, some argue, imprudent decisions made by governors and federal officials that have produced a worker shortage. Common sense tells us that if you provide a living salary to workers not to work, they will not work.

High business taxes, an increase in the supply of money flowing from private pockets to the public purse, and labor shortages have produced too few goods, resulting in inflation – too many dollars chasing too few goods.

The high price of goods and services may also be attributed to a continuing effort by progressives in the United States to repeal a central law of a free-market economy, the law of supply and demand, which holds that when demand is a constant and supply is diminished, prices on all goods and services rise. The rise in prices has less to do with the greed of billionaire CEOs than a Darwinian survival-of-the fittest-impulse in over-regulated markets centrally directed by Washington politicians. Large business can survive a large regulator drag on profits. Higher taxes and an increasing regulatory burden swamp smaller businesses and, of course, make it much easier for the larger fish to swallow the minnows.

The empty shelves in Russian stores during the good old days of the Soviet Union were attributed by underpaid “workers of the world” in Russia to central planning. In the so-called “captive nations,” the necklace of states now threatened militarily by Vladimir Putin, workers used to joke among each other, “We pretend to work, and they pretend to pay us.”

The Democratic Party program runs against the grain of good sense. Every worker in the United States knows that personal debt should be discharged by responsible debt holders willing to cut spending and pay down the debt.

Temporary reductions in taxes are insufficient to pay down a debt in Connecticut that has swelled over the years to about $57 billion. And given past performance, no one in the state can be certain that increased taxes will be put to such purposes by an administrative apparatus, growing daily, that had in the past raided various Connecticut lockboxes to pay for current expenses.

The solution to Connecticut’s most pressing economic problems is disarmingly simple: Enrich the state’s creative middle class by cutting taxes and regulations, pay down debt, and work hard to dissolve the entangling alliances between a tax-thirsty government and an even more tax-thirsty conglomeration of various state employee unions.

Don Pesci is a Vernon-based columnist.

The Mystic River Bascule Bridge, built in 1922, carries US 1 over the Mystic River in Connecticut. The famous span connects Groton with the Stonington.

Factory as cuteness preventive

The old Rossie Velvet Mill in Stonington, Conn.

“The factory is a good prevention against quaintness; it removes from the village a possibly ‘cute’ edge.’’

— Anthony Bailey (1933-2020), in his book In the Village, based on the Englishman and New Yorker writer’s 10 years of living in Stonington, Conn., a generally pretty coastal town.

New England's aromatic mix

The James Merrill House in Stonington, once the home of the famed late poet of that name (1926-1995) and now a temporary place for writers to live and work in

“The aroma of New England is a mix of mulchy leaves, the hearth, cider, and crisp cold sea.’’

— L.M. Browning (born 1982) is a Connecticut-based writer and journalist. She grew up in Stonington, a wealthy waterfront town at the eastern end of Long Island Sound that’s well known for the writers, photographers and painters it has long attracted, especially from New York City.

Stonington Harbor Light

'Grit in the bones'

Stonington (Conn.) Harbor Light was built in 1840 and is a well-preserved example of a mid-19th Century stone lighthouse. The lighthouse was taken out of service in 1889 and is now a local history museum. Stonington once was an important fishing and whaling port but is now mostly known a summer place for affluent people, especially from New York City. Many writers (such as the late poet James Merrill) and painters have also had homes there.

“The shades of New England are here on my skin. Brine in the blood, grit in the bones, and sea air in the lungs.’’

— L.M. Browning, in Fleeting Moments of Fierce Clarity: Journal of a New England Poet. She grew up in Stonington, Conn.

Early morning gull

See www.nivaartwork.com and galateafineartcom

“Lobster Co-Op in Stonington {Maine} ‘‘ (oil) , by Niva Shrestha in Galatea Fine Art’s online gallery. This text ran with it:

“The first sound one hears is the gull calling the morning. It has been a long work day, and it seemingly was never over. The dawn calls to duty, to awaken todoing-ness, sleep and rest a dim memory. But the day is a blessing, a legacy to generations past and future.’’

Tougher than the Devil

Daniel Webster

“If two New Hampshiremen aren’t a match for the Devil, we might as well give the country back to the Indians.’’

Stephen Vincent Benet (1898-1943), in his short story “The Devil and Daniel Webster’’. The tale centers on a New Hampshire farmer who sells his soul to the Devil and is defended by Daniel Webster (1782-1852), a fictional version of the 19th Century American statesman, lawyer and orator.

Mr, Benet’s gravestone in the Evergreen Cemetery in Stonington. Conn.

'On my skin'

Lighthouse in Stonington

“The shades of New England are here on my skin. Brine in the blood, grit in the bones, sea air in the lungs.’’

— L.M. Browning, in Fleeting Moments of Fierce Clarity: Journal of a New England Poet. She grew up in Stonington, Conn., on Long Island Sound