David Warsh: It may be too late but here’s a suggestion on saving print newspapers

Newspapers rolling off the press

— Photo by Knowtex

1896 ad for The Boston Globe

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

It may have been pure coincidence that strains on American democracy increased dramatically in the three decades after the nation’s newspaper industry came face to face with digital revolution. Then again, the disorder of the former may have something to do with the latter.

Since 2001, the last good year, daily circulation of major metropolitan newspapers has been plummeting. An edifying survey last year found that The Wall Street Journal, at the top of the field, delivered more print copies daily (697,493) than its three next three competitors combined: The New York Times (329,781), USA Today (149,233) and The Washington Post (149,040).

All but one of the top 25 newspapers reported declining print circulation year-over-year. The Villages Daily Sun, founded in 1997 in central Florida, not far north of Orlando, was up 3 percent, at 49,183, ahead of the St. Louis Post Dispatch and the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

Is there still a market for print newspapers? Maybe, maybe not. There is probably only one good way to answer the question. I’d like to suggest a simple experiment: compete on price.

The New York Times Company bought The Boston Globe 30 years ago this week for $1.13 billion, in the last days of the golden age of print journalism. The Times ousted the Globe’s fifth-generation family management in 1999, installed a new editor in 2001, and, for 10 years, rode with the rest of the industry over the digital waterfall.

The Globe, whose 2000 circulation had been roughly 530,000 daily and 810,000 Sunday, broke one great story on the way down. Its coverage of the systemic coverup of clerical sexual abuse of minors in the Roman Catholic Church beginning in 2002 has reverberated around the world. The story produced one more great newspaper movie as well – perhaps the last — Spotlight. Otherwise the New York Times Co. mismanaged the property at every opportunity, threatening at one point to simply close it down. It finally sold its New England media holdings in 2013 to commodities trader and Boston Red Sox owner John W. Henry for $70 million.

Since then, the paper has stabilized, editorially, at least, under the direction of Linda Pizzuti Henry, a Boston native with a background in real estate who married Henry in 2009. Veteran editor Brian McGrory served for a decade before returning to column writing this year. Nancy C. Barnes was hired from National Public Radio to replace him; editorial page editor James Dao arrived after 20 years at the Times. A sustained advertising campaign and new delivery trucks gave the impression the Globe was in Boston to stay.

Henry himself showed some publishing flair, starting and selling a digital Web site, Crux, with the idea of “taking the Catholic pulse,” then establishing Stat, a conspicuous digital site that covers the biotech and pharmaceutical industries. Henry’s sports properties – the Red Sox, Britain’s Liverpool Football Club, a controlling interest in the National Hockey League’s Pittsburgh Penguins, and a 40 percent interest in a NASCAR stock car racing team, are beyond my ken.

There is, however, one continuing problem. The privately owned Globe is thought to be borderline profitable, if at all. It seems to have followed the Times Co. strategy of premium pricing. Seven-day home delivery of The Times now costs $1305 a year. Doing without its Saturday and overblown Sunday editions brings the price down to $896 for five days a week. The year-round seven days a week home delivery price for The Globe is posted in the paper as $1,612, though few subscribers seem to pay more than $1200 a year, to judge from a casual survey.

In contrast, six-day home delivery of WSJ costs $720 a year. The American edition of the Financial Times, in some ways a superior paper, costs $560 six days a week, at least in Boston. It is hard to find information about home-delivery prices for The Washington Post, now owned by Amazon magnate Jeff Bezos. But $170 buys out-of-town readers a year’s worth of a highly readable daily edition.

So why doesn’t The Globe take a deep breath and cut home-delivery prices to an annual rate of $600 or so, to bring its seven-day value proposition in line with those of the six-day WSJ and the FT? The Globe trades heavily on legacy access to wire services of both The Times and The Post; it is not clear how this would fit into such a bargain with readers. Long-time advertising campaigns would be required to make the strategy work.

That would be taking a leaf from The Times’s long-ago playbook. In 1898, facing falling ad revenues amid malicious rumors that it was inflating its circulation figures, publisher Adolph Ochs, who had bought the daily less than three years before, cut without warning its price from two cents to a penny, to the astonishment of his principal New York competitors on quality, The Herald and The Tribune. He quickly gained in volume what he gave up for the moment in revenue, raised the price a year later, and never looked back. The move has been hailed ever since as “a stroke of genius.”

Would it work today? It might. If it did, it would constitute a proof of concept, an example for all those other formerly great metropolitan newspapers to consider in hopes of creating a standard for two-tier home-delivery pricing: one price for the national dailies; a second, slightly lower price for the less-ambitious home-town sheet.

It might force The Times to cut back on its Tiffany pricing strategy, to take advantage of once-again growing home-delivery networks, and get print circulation increasing again, after two decades of gloomy decline.

Even digital publisher of financial information Michael Bloomberg might be persuaded to put his first-rate news organization to work publishing a thin national newspaper, on the model of the FT. Print newspapers have a problem with pricing subscriptions to their print daily papers. It is time for industry standards committees to begin considering the prospects.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay originated.

“Newspaper readers, 1840,’’ by Josef Danhauser

David Warsh: In the press, a dose of vicarious shock

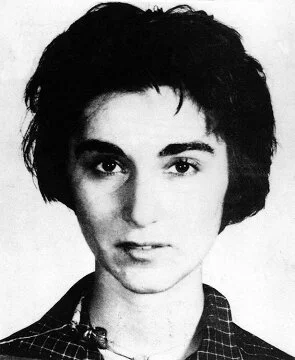

“Kitty” Genovese

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

It was a famous story from The New York Times in 1964.

37 Who Saw Murder Didn’t Call the Police; Apathy at Stabbing of Queens Woman Shocks Inspector

by Martin Gansberg

For more than half an hour 38 respectable, law‐abiding citizens in Queens watched a killer stalk and stab a woman in three separate attacks in Kew Gardens.

Twice the sound of their voices and the sudden glow of their bedroom lights interrupted him and frightened him off. Each time he returned, sought her out and stabbed her again. Not one person telephoned the police during the assault; one witness called after the woman was dead.

That was two weeks ago today. But Assistant Chief Inspector Frederick M. Lussen, in charge of the borough’s detectives and a veteran of 25 years of homicide investigations, is still shocked.

He can give a matter‐of‐fact recitation of many murders. But the Kew Gardens slaying baffles him — not because it is a murder, but because the “good people” failed to call the police.

The story of the killing of Catherine (“Kitty”) Genovese was widely read at the time and admired for decades. It made the reputation of A. M. Rosenthal, the metropolitan editor who caused it to be written and who argued its way onto the front page. Rosenthal’s own gloss on the story, “Thirty-Eight Witnesses,’’ was published within months. He rose rapidly at The Times, to be executive editor in 1977-1987, and for a dozen years after that, a columnist.

It turns out there was a backstory, too. In his book, Rosenthal disclosed how he himself had got the story, from Michael J. Murphy, theNew York City police commissioner, over lunch at Emil’s Restaurant and Bar on Park Row, near City Hall.

“Brother,” the commissioner said, “that Queens story is one for the books.”

Thirty-eight people, the commissioner said, had watched a woman being killed in the “Queens story,” and not one of them had called the police to save her life.

“Thirty-eight?” I asked.

And he said, “Yes, 38. I’ve been in this business a long time, but this beats everything.”

I experienced then that most familiar of newspapermen’s reaction — vicarious shock. This is a kind of professional detachment that is the essence of the trade — the realization that what you are seeing or hearing will startle a reader.

Some readers, including a television police reporter, Danny Meehan, doubted details of the story as soon as it appeared. Over the years various embellishments, inconsistencies, and inaccuracies came to light. In 2004 The Times took account of them. They did not change the essential fact at the heart of the story — a woman had been murdered in the middle of the night in a populous neighborhood, steps from her door. When her killer, Winston Moseley, died in prison, at 82, Robert McFadden summed up in a Times obituary:

The article grossly exaggerated the number of witnesses and what they had perceived. None saw the attack in its entirety. Only a few had glimpsed parts of it, or recognized the cries for help. Many thought they had heard lovers or drunks quarreling. There were two attacks, not three. And afterward, two people did call the police. A 70-year-old woman ventured out and cradled the dying victim in her arms until they arrived. Ms. Genovese died on the way to a hospital.

I thought of the Genovese story because something of the sort happened in my neighborhood earlier this month — but in reverse. On Election Day, a 40-year-old woman was hit and killed in a crosswalk midday by a pickup truck.

Leah Zallman, 40, the mother of two young sons, was on her way home after voting at lunch time. She was the director of research at the Institute for Community Health, a primary-care physician at the East Cambridge Care Center, and an assistant professor of medicine at the Harvard Medical School

Talk about local apathy, at least in the public realm! Television stations reported the accident the day it happened. After that the news was only slowly shared, without details, first by the public school’s parent association, then on community Google groups. The city took a week to acknowledge on its Web site that it had happened. It was 10 days before The Boston Globe took account of it, and then only with a touching remembrance by a columnist free of any details of the accident itself, not even those that had been posted by the city:

An initial investigation suggests that the operator of the vehicle, an employee of the City of Somerville who was on duty at the time but operating their personal vehicle, had been attempting to take a left turn onto Kidder Avenue from College Avenue. They remained on the scene following the crash. Pending the results of an investigation [by the Middlesex District Attorney’s Office and Somerville Police], the employee has been placed on paid administrative leave…. No charges have been filed at this time.

We’ll learn more eventually from the Middlesex County investigation, including the identity of the driver, reported to be a Somerville building inspector, and the circumstances of his day. I wish that there were some local hero, a Rosenthal type, who could document how Zallman’s death could remain on the down-low for more than a week. (City councilors argued the details of the accident with the mayor and his Mobility Department behind the scenes.) Last year, when two women were hit after dark in a crosswalk, one of them killed, by a hit-and run driver less than mile away, it was big news. This time there were no flowers at the site, no other reminder of what happened at the busy crossing, no public outcry, no political outrage, only a lingering sense of shock.

It’s a commonplace that the invention of online search advertising has brought most metropolitan newspapers to their knees. In October the once-mighty Boston Globe reported print circulation of 84,000 daily and 123,000 Sunday, down from 530,000 and 810,000 respectively 20 years ago. The national papers have managed to hold their own so far. That small cities like Somerville, those of 100,000 people or so, haven’t found a way to rejuvenate the provision of local news bodes ill for their public life. With local journalism withering on the vine, we don’t have publicity, hence public outrage, over a traffic death that shouldn’t have happened. We don’t have accountability, either, sufficient to deter careless driving. Pickup trucks, in particular, often seem to confer a dangerous sense of privilege upon their drivers.

To be clear, I don’t think that what Abe Rosenthal did in 1964 was wrong, or wicked, in any sense, though in retrospect its self-aggrandizing subtext is hard to miss. Call it inflated-for-the-good-of-us-all journalism, the presentation of facts spiced with a special sauce of indignation for the purpose of making a point.

The Times had reported Genovese’s murder as an unvarnished matter of fact, when it occurred, in a short item buried deep inside the paper a couple of weeks before. To return to the story with additional facts — police commanders’ indignation – was in line with the performance of the newspaper’s duty to offer occasional moral instruction along with the news. But the embellishment went too far, and tarnished The Times’s most valuable asset, readers’ trust.

Newspapers have traditionally tried to rile up readers in a good cause in the three centuries they have been democracies’ dominant form of public communication. For a wry and affectionate look behind the scenes of inflated-for-the-good-of-us-all journalism at The Times in executive editor Rosenthal’s heyday, find a used copy of I Shouldn’t Be Telling You This, by Mary Breasted. Or rent a copy of Ron Howard’s brilliant 1994 film The Paper.

It seems the case that The Times has practiced more indignation-fueled news recently than usual – its 1619 Project, for example, provoked columnist Bret Stephens’s stinging dissent. The roots are the same as those Rosenthal identified in 1964: the experience of shock in the face of the facts. Rosenthal’s proud claim as editor was that “he kept the paper straight.” Think that is easy in times like these? Occasional large helpings of indignation are better than no news at all.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first ran.

David Warsh: Two developments in big newspapers economic drama

In The New York Times newsroom.

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

Like most people, I am forever curious about what constitutes the baseline narrative of our times – all the more so for being the news business. My routine for some years now has been to skim the front pages of four newspapers when I get up, then when I come home at night read the three newsprint editions I received in the morning — The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and the Financial Times. The Washington Post I read on the Web.

I don’t watch any television, except when I travel, but I listen to NPR for half an hour in the morning. I subscribe to four magazines (The Economist, Bloomberg Businessweek, The New Yorker and Science). I look at Politico’s Web site once or twice a day. And last week I read most of Merchants of Truth: The Business of News and the Fight for Facts (2019), by Jill Abramson, former executive editor of The New York Times.

The daily newspapers are definitely where I get my news. I often think that entering the worlds of their news pages is like listening to a quartet: the Times is a daily violin, exciting and emotional; The Post resembles a viola, warmly supportive of The Times’s themes, but less jittery; the WSJ is something of a cello, understated and lower-pitched; and the FT, a different voice altogether, is more like a piano.

As in any quartet, each institutional player seems well aware of what the others are doing, at least as a daily matter. Long term, I am not so sure. At least in my experience, two developments stand out.

The first is purely local. After some years of disruption, my three papers are always there on the porch in the morning. It is dispiriting to see, as I walk to work, how few houses take delivery of one or the other national papers, compared to 15 years ago – never mind the precipitous decline of The Boston Globe, my local newspaper. But the evidence is of a newsprint-delivery service that once again takes itself seriously as a going concern, after several years of disruption.

The other development has to do with the price that readers pay for their annual print subscriptions: the Times, $1,092; the WSJ, $540; the FT, $406; and The Post, $150 for digital access, plus second subscription to the paper to give away, a month at a time.

Is the print edition of The Times really worth twice what the WSJ charges for its own? If I could read only one newspaper, which would I choose? I understand that the Times’s pricing policy is, in essence, a branding device, the Tiffany among newspapers, and all that. The Times’s cultural and science reporting has been without peer, though cultural reporting is definitely in decline.

Abramson’s book supports that strategy. The tradition of its former staffers burnishing the paper’s reputation goes back to Gay Talese’s The Kingdom and the Power (1969), about The Times; The Powers That Be (1979), by David Halberstam; and The Trust: The Private and Powerful Family behind The New York Times (1999), by Susan Tifft and Alex Jones.

Halberstam weaved together The Times’s story with four other organizations that had assumed the mantle of media royalty: Henry Luce’s Time Inc.; William Paley’s CBS; Katharine Graham’s Post and the Chandler family’s Los Angeles Times. Forty years later, CBS News and Time are ghosts of their former selves, and the LA Times has a new owner.

Abramson intertwines the tale of her paper’s recent ups and down with the story of the Graham family’s sale of The Post to Amazon magnate Jeff Bezos, and the tales of two all-digital up-and-comers that The Times perceives as threats, BuzzFeed and Vice Media. Neither organization has yet delivered on its early promise. Web-based news start-ups Axios and Quartz may pose more serious challenges, not to mention well-established competitors, such as Reuters and Bloomberg News.

Meanwhile, the New York Times Co. reported earlier this month that digital ad revenue had surpassed print ad revenue in the quarter that ended Dec. 31 for the first time in the company’s history. Digital ad sales were up 23 percent, as opposed to 5 percent increase in advertising revenues overall in the period.

That’s good news, surely, except that the surging growth in The Times’s digital-only subscribers may disguise shrinking circulation of its costly newsprint edition, where a full page of advertising costs more than $100,000, according to Abramson. It’s been conventional wisdom for years that print editions are doomed – that it is only a matter of time before they disappear.

Yet print ads have continued to keep newspapers afloat. It’s not the majority of consumers of news who prefer print to digital devices – just a relatively small audience of elite readers for whose attention some kinds of advertisers are willing to pay, all the more so once they see print editions culturally supported by, among others, the papers themselves.

The contest between the very different print and digital pricing strategies of The Times, on the one hand, and the WSJ and the FT on the other, has implications for the long-term narrative of American politics. Who will call the tune? (Because I don’t see the print edition of The Post, I have no real idea what’s going on there.) Those books by Times authors scarcely mention the biggest Times competitor for influence since the 1960s, the WSJ.

Today’s contest between the Murdoch and Sulzberger families deserves more attention than it has been getting. It has implications for the rest of the newspaper industry as well. How many more copies of the big regional newspapers – LA Times, Chicago Tribune, Boston Globe – would flop up on front porches if subscriptions were priced more like the WSJ instead of The Times? In their golden era, before the advent of search advertising, American newspapers resembled symphonies. If the industry paid more attention to the importance of price, perhaps newspapers might become chamber orchestras again.

David Warsh, an economic historian and veteran columnist, is proprietor of economicprincipals.com, where this essay first ran.

Llewellyn King: The Bradlee I knew and the creation of 'Style'

Ben Bradlee, who died Oct. 21 at 93, did not so much edit The Washington Post as lead it.

Where other editors of the times would rewrite headlines, cajole reporters and senior editors, and try to put their imprint on everything that they could in the newspaper, that was not Bradlee’s way. His way was to hire the best and leave them to it.

Bradlee often left the building before the first edition “came up,” but it was still his Washington Post: a big, successful, hugely influential newspaper with the imprimatur of one man.

Bradlee looked, as some wag said, like an international jewel thief; someone you would expect to see in one of those movies set in the South of France that showed off the beauty of the Mediterranean and beauties in bikinis while the hero planned a great jewel heist.

I worked for Bradlee for four years and we all, to some degree, venerated our leader. He had real charisma; we not only wanted to please him, but also we wanted to be liked by him.

Bradlee was accessible without losing authority; he was all over the newsroom, calling people by their first names and sometimes by their nicknames, without surrendering any of the power of his office. He was an editor who worked more like a movie director rather than the traditionally detached editors I had known in New York and London.

The irritation at the paper -- and there always is some -- was not so much that Bradlee was a different kind of editor, but that he had a habit, in his endless search for talent, of hiring new people and forgetting, or not knowing, the amazing talent already on the payroll. The Post was a magnate for gifted journalists, but once hired, there were only so many plum jobs for them to do. People who expected great things of their time at the paper were frustrated when relegated to a suburban bureau, or obliged to write obituaries for obscure people.

Yet we knew we were putting out a very good paper and, in some ways, the best paper in the United States. This lead to a faux rivalry with The New York Times. Unlike today, very few copies of The Times were sold in Washington, and even fewer Washington Posts were sold in New York.

Much has been made of Bradlee’s fortitude, along with that of the publisher, Katherine Graham, in standing strong throughout the Watergate investigation that led to President Nixon's registration. But there was another monumental achievement in the swashbuckling Bradlee years: the creation of the Style section of the newspaper.

When Style first appeared, sweeping away the old women’s pages, it went off like a bomb in Washington. It was vibrant, rude and brought a kind of writing, most notably by Nicholas von Hoffman, which had never been seen in a major newspaper: pungent, acerbic, and choking on invective. Soon it was imitated in every paper in America.

The man who created Style was David Laventhol, who came down from New York to fashion something new in journalism. Laventhol was a newspaper mechanic without equal, but Bradlee was the genius who hired him.

When I worked at The Post, I interacted a lot with Bradlee; partly because we enjoyed it, and partly because it was the nature of the work. I knew a lot about newspaper production in the days of hot type and he affected not to. That gave Bradlee the opportunity to exercise one of his most winning traits: disarming candor. “I don’t know what’s going on here,” he said one frantic election night in the composing room.

But when it came to big decisions, Bradlee knew his own mind to the exclusion of the rest of the staff. The nerve center of a newspaper is its editorial conferences -- usually, there are two every day. The first conference is to plan the paper; the second is a reality check on what is new, and how the day is shaping up.

At these conferences, Bradlee would listen from behind his desk. But when he disagreed with the nine assistant managing editors, and others who needed to be there, he would put his feet on the desk, utter an expletive and cut through fuzzy conversation like a scimitar into soft tissue. As we might say nowadays, he had street smarts. They were invaluable to his editorship and to his charm.

Llewellyn King (lking@kingpublishing.com) is executive producer and host of “White House Chronicle” on PBS. He is a longtime publisher, broadcaster, writer and international business consultant.