Perspectives on transparency

“Transparency’’ — a show by members of New England Wax

May 21 – June 27, 2024

Wellfleet Preservation Hall

335 Main Street in Wellfleet, MA

Reception: Saturday, June 1, 5–7pm

Open to the public Tuesday – Friday 10am–4pm, and during events.

Transparency, featuring works from 27 artists, seeks to investigate the concept of transparency in all its forms. Wax is a mutable material, capable of changing its form and adapting to its environment. Utilizing light, texture, form, and color, works in this exhibition play with the literal qualities of transparency, with pieces that are both ethereal or illusory and grounded in the physical world. Others explore the metaphorical dimensions of transparency, examining issues of trust, accountability, and communication. Through the works of a range of artists working with wax, the exhibition invites viewers to reflect on the significance of transparency in our society and explore its relationship to power, communication, and the human experience. Each piece in the exhibition offers a unique perspective on transparency and its many layers of meaning, creating a cohesive and thought-provoking narrative.

Wellfleet Preservation Hall is a vibrant cultural center that uses the transformational power of the arts to bring people together and impact positive change. It is a community center that celebrates people from all backgrounds and walks of life.

335 Main Street, Wellfleet, MA • 508-349-1800

Exhibiting Artists:

Katrina Abbott

Lola Baltzell

Edith Beatty

Hilary Hanson Bruel

Lisa Cohen

Angel Dean

Pamela Dorris DeJong

Heather Leigh Douglas

Hélène Farrar

Dona Mara Friedman

Kay Hartung

Anne Hebebrand

Sue Katz

Janet Lesniak

Ross Ozer

Deborah Peeples

Deborah Pressman

Stephanie Roberts-Camello

Lia Rothstein

Melissa Rubin

Ruth Sack

Sarah Springer

Donna Hamil Talman

Marina Thompson

Lelia Stokes Weinstein

Charyl Weissbach

Nancy Whitcomb

‘As Covid morphed’

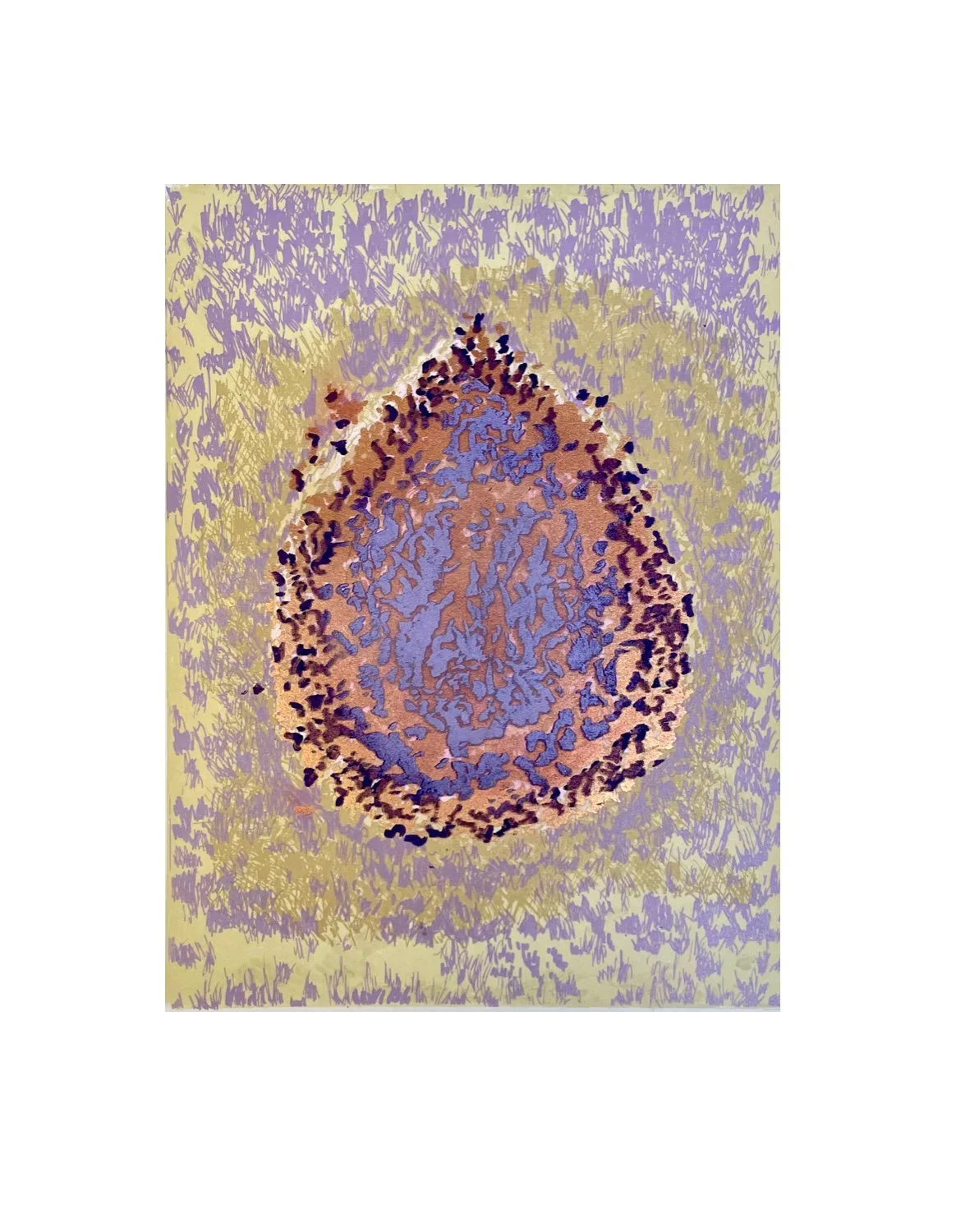

“Lavender Light,’’ by Phyllis Ewen, in her show “My Mind’s Eye,’’ at Kingston Gallery, Boston, March 1-March 31. She lives in Somerville and Wellfleet, Mass.

She says:

“As Covid-19 continued and morphed, my art turned inward. A new series of lithographs reflected my changing state of mind and is continuing as is the pandemic. These lithographs come from MRI images of a brain.’’

“Guglielmo Marconi built the first transatlantic radio transmitter station on a bluff in South Wellfleet in 1901–1902. The first radio telegraph transmission from the United States to England was sent from this station on Jan. 18, 1903, a ceremonial telegram from President Theodore Roosevelt to King Edward VII. Most of the transmitter site is gone, however, as three quarters of the land it originally encompassed has been eroded into the sea. The South Wellfleet station's first call sign was "CC" for Cape Cod.’’

— Edited version of a Wikipedia entry

'Friendly in the dark chill'

A Leonid meteor.

"The sky is streaked with them

burning hole in black space --

like fireworks, someone says

all friendly in the dark chill

of Newcomb Hollow in November,

friends known only by voices.''

-- From "Leonids Over Us,'' by Marge Piercy, who is referring to the Leonids meteor shower. Newcomb Hollow is in Wellfleet, on Outer Cape Cod.

Restoring the ecology of the Herring River estuary

Enjoying the Herring River.

A $700,000 Massachusetts state grant was recently awarded to help advance the restoration of the Herring River estuary in Wellfleet and Truro, one of the largest ecology-restoration projects in the Northeast. The grant leverages a total of $985,034 in funding for the project in fiscal years 2017 and 2018 from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Restoration Center.

Spanning some 1,000 acres across the Cape Cod National Seashore, the Herring River estuary hosts one of the largest river and wetland systems on Cape Cod. In 1909, a dike was built across the river’s mouth, severing its connection to Wellfleet Harbor and the life-giving tides of the Atlantic Ocean. Without that connection, the salt marshes decayed, the river turned acidic, shellfish beds were contaminated by bacteria, and multiple fish kills resulted from low dissolved oxygen. The loss of tidal flow transformed this once-thriving and productive coastal ecosystem into the highly degraded landscape found there today.

The towns of Wellfleet and Truro are working with the National Park Service, the Department of Fish and Game’s Division of Ecological Restoration (DER) and other partners to revive the health of the Herring River and its wetlands. The project will rebuild the main dike at the river’s mouth and make other improvements across the estuary, allowing carefully controlled restoration of tidal flow to the ecosystem while protecting low-lying roads and other structures from flooding.

Reconnecting the estuary to the ocean will improve water quality, increase habitat productivity for fisheries and other wildlife, restore large areas of shellfish beds, and enhance boating, fishing, and other commercial and recreational opportunities, according to state officials.

“We look forward to the day when a restored Herring River estuary provides much-improved habitat for waterfowl, shorebirds, river herring, white perch, and other fish and wildlife,” Department of Fish and Game Commissioner Ron Amidon said. “The project will also greatly enhance people’s access to the natural environment by improving opportunities for shellfish harvest, fishing, boating, and other outdoor recreation.”

The DER grant will also support engineering design and permitting to prepare the project for construction. The project is being managed by Friends of Herring River, a nonprofit organization based in Wellfleet.

'Botanical archaeology'

"Highway Into the Void'' (oil on canvas), by PETER WATTS, in his June 20-July 6 show at the Berta Walker Gallery, Provincetown.

The blurb for his show says that "he is always aware of the history of human touch that nature quickly covers over.'' The gallery calls his approach "botanical archeology.''

It said that Mr. Watts, who lives in Wellfleet, "sometimes paints houses based on his knowledge of local history coupled with discoveries like a long-abandoned cellar hole....A stand of pines on top of a knoll is a former pasture returned to seed, surrounded by the oak forests that will one day conquer it.''

Of course, much of New England, especially mostly densely populated southern New England, was once farmland. Despite the overall increase in the region's population, much of it has gone back to scrub or woods, leaving layers of ghosts.

The rise of "locavore'' agriculture, whose products are targeted at affluent suburbanites and urbanites, seems unlikely to return much of this land to open farmland, as popular as those farmers' markets, heavy laden with "organic'' produce, seem to be.

Through all this are what Mr. Watts sees as "nature's changing patterns and the patterns that repeat themselves.'' He said he used to be "more interested in the landscape itself. Now I look at how an abstract element of a landscape feels.''

This reminds me (Robert Whitcomb) of Alan Weisman's eerie coffee-table book The World Without Us, a nonfiction book about what the human-built environment might look like when humans disappear.