William Morgan: Ruminations on an old postcard from Maine

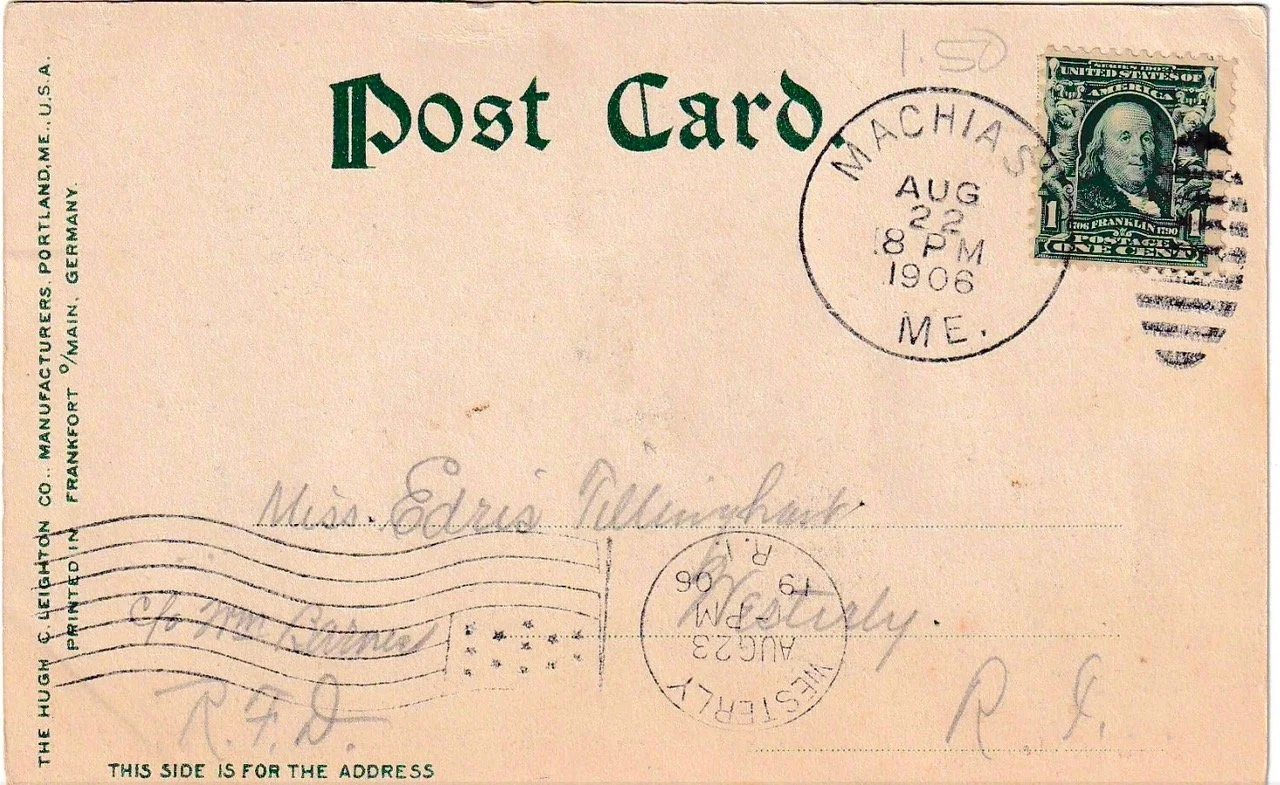

Porter Memorial Library, Machias, Maine. Hand-colored postcard.

Once again, an antique postcard yields memories as well as mysteries. My investment of $1.50 to buy an old card led to down-the-rabbit-hole ruminations.

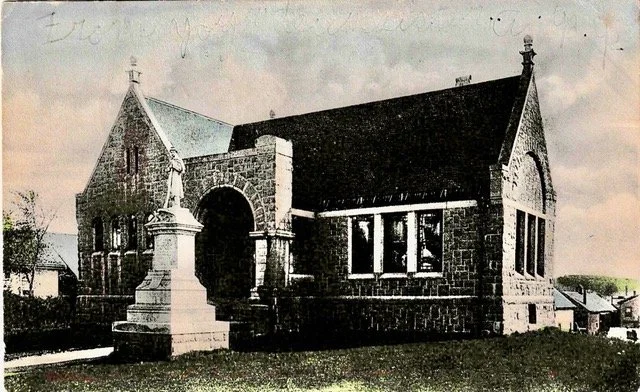

Posted in Machias on Aug. 22, 1906 (Theodore Roosevelt was President); Maine had been a state for only 86 years. The sender, from what we can make out from the pencil scratches on the picture side of the card, was the sister of the recipient, Miss Edris Tillinghast. Tillinghast is a Rhode Island name, but Edris strikes one as one of those late Victorian family names, yet it is well enough known in Wales. Was Miss Edris visiting in Westerly? (Her address is in care of “Wm. Barnes, RFD” (Rural Free Delivery) – her family rusticating on a farm, perhaps)? Or was the sister traveling in far Downeast Maine?

Post card from Hugh C. Leighton Co., Portland, but printed in Germany

The Tillinghast sisters and their undocumented peregrinations may had faded into the mists of time, but the library building in the Washington County seat has remained pretty much unchanged. Chicago businessman and Machias native Henry Holmes Porter gave the money to erect the library in memory of his father, Rufus King Porter, in 1891.

The architect of the Porter Library was George Clough, who hailed from Blue Hill, Maine, and was a successful practitioner in Boston. He designed the Suffolk County Courthouse, on Pemberton Square, Boston, and he was that city’s first City Architect, a position to which he was elected in 1876 and served for seven years. He also designed the public libraries for the Maine towns of Rockland, Bucksport and Vinalhaven.

Postcard of Buck Memorial Library, Bucksport.

Clough’s inspiration for Machias was the Romanesque Revival-style libraries of Henry Hobson Richardson in such suburban Boston towns as Woburn, North Easton and Quincy. Richardson was best known as the architect of Trinity Church at Copley Square in Boston, but his small-town libraries are among his most satisfying works. Clough was one of many New England library builders who borrowed from the Richardsonian formula of monumental reading room, wing for the stacks and ceremonial civic entrance.

Crane Memorial Library, by Henry Hobson Richardson, in Quincy, Mass.

-- Photo by William Morgan

Providence-based writer and photographer William Morgan is the author of a number of books on New England architecture, including A Simpler Way of Life: Farmhouses of New York and New England and Monadnock Summer: The Architectural Legacy of Dublin, New Hampshire.

William Morgan: It's time to retire stop signs

— Photo above by La Cara Salma

— Photos by William Morgan

Let’s face it, the days of the stop sign are over. The stop sign is an anachronism, as are simple courtesy and turn signals. Nobody pays attention to them anymore, so why do we keep them around? A stop sign can be confusing to, say, older people who might actually come to a complete stop, thereby creating a hazard and slowing the progress of all the other drivers who either ignore or do not recognize the purpose of the red metal octagon.

Stand at a busy street corner for a few minutes and count the number of cars that do not heed the stop sign. My experience of such an exercise invariably shows that a majority of motorists sail right through intersections without stopping; they might slow down for a moment, perhaps hesitating, vaguely remembering a forgotten but once ingrained habit. During a recent brunch at a restaurant on a busy Providence corner, I watched as nine out of ten cars failed to stop. The particular location is a block from an elementary school, yet the presence of crossing guard hardly seems make a dent in transgressions.

Rhode Islanders are certifiably among the nation’s worst drivers–the drivers least likely to abide by traffic rules. But I expect disobeying stop signs is a common American phenomenon–no one expects us to drive like the Swiss or the Swedes. Perhaps there are some national characteristics–anti-authoritarianism, visual impairment, stupidity–that make us want to transform a reasonable few extra seconds of pausing into a game of automotive chicken.

Maybe there’s a plot by insurance companies to raise premiums, and there’s is an army of lawyers who flood the airwaves and crowd the sides of highways with billboards asserting that they can monetize your car crash.

Eventually, I will get rear-ended by a distracted mother in her Ford Subdivision or a hedge-funder in his Mercedes Afrika Korps, or mauled by a super aggressive-looking pickup truck, the drivers all texting. Until then, I will try to retain my belief that obeying traffic rules is part of a greater social contract. Yet the failure to heed stop signs suggests a larger breakdown of society as a whole.

Like the use of cell phones while driving (illegal in my state), such actions point to a lack of connection with the world around you and your species. If you don’t make eye contact with a pedestrian, a bicyclist or another driver, you are closing down an opportunity to interact with another human, a fellow citizen. When I slow down or pull out of the way on a narrow street so that an oncoming car can pass through, I rarely get an acknowledgment, a wave of the hand, a mouthed thank you. I am just some unimportant loser in an 18-year-old Volvo who ought to give way to the driver of a hurrying urban assault vehicle on a self-important mission. My wife, however, says I am just invisible.

In neighboring Massachusetts, stop signs at dangerous intersections are getting blinking lights around their perimeters. This seems to me like the third stop light that was mandated on cars a few decades ago–and we know how effective they have been on cutting down on tailgaiting. Such well-intentioned gestures are only short-term bandages putting off the eventual removal of all these useless stop signs.

Let the all-out free-for-all begin.

William Morgan is an architectural writer based in Providence. His latest book is Academia: Collegiate Gothic Architecture in the United States.

William Morgan: Why Providence is indeed one of the 'Best Towns'

The Rhode Island State House is just the crowning example of brilliant civic architecture in Providence. Few other American cities can match Providence in the richness of its architectural patrimony.

—- Photo by William Morgan

Providence got a welcome pat on the back when CNN Travel recently ranked it Number 2 on its list of “Best Towns in America To Visit’’; Richmond, Va. was Number 1. Our high scores included Art, Architecture, Design and Food (of the other nine cities, only Macon, Ga., got a nod for its historic buildings). Such a positive national spotlight on Rhode Island’s capital is briefly heartwarming, but it barely hints at why Providence is one of the best towns anywhere in which to live.

Americans seem obsessed with lists and rankings, most of which are so superficial as to be meaningless. The worst are the college ratings, which seem only to increase applications to fewer schools (often called “elite’’) and to create a general atmosphere of insecurity for all the rest. (Examples of criteria used: Last time I checked, The New York Times’s list of the 300 Best Colleges had Providence College dead last in terms of student diversity; the University of Chicago held the bottom rung on the ladder for social life.)

The Zumper real-estate study listed Providence as 98th in 100 spots for best city for this year’s college graduates. Such metrics as median rents and the unemployment rate produced findings giving top spots to far-from-the- ocean Minneapolis, Columbus and Oklahoma City, while admittedly much more vibrant cities with higher costs of living, such as Boston or New York, lagged far behind. Where are the rankings for character, for beauty, for soul?

Beacon Hill, Boston. Who would trade this for Grand Rapids or Duluth?

— Photo by Willliam Morgan

When I was a professor of urban studies at the University of Louisville, students would often ask me what makes a great city. Somewhat tongue in cheek, yet also in a way deadly serious, I said that a great city was one that poets would write poems about and to which musicians would write love songs (“I left my heart in Duluth” doesn’t work). A few other pedagogical chestnuts: All great cities are on water. Street life and the strength of the neighborhoods are key indicators of livable cities. And the acceptance in a city of its gay citizens is also a strong indication of its livability.

A collection of the author’s columns that he wrote as architecture critic of the Louisville Courier-Journal were published as this book.

When my wife, Carolyn, and I decided to leave Kentucky for a new home somewhere in New England, we tried to heed my own urbanism lessons. We agreed that we would seek the ideal place to live in, and then look for work, rather than let a job dictate where we would settle. We drew up a stringent list of urban wants, headed by proximity to the ocean and a city’s strong sense of its history. Needing to work, we wanted a city with several colleges and universities where we could teach.

Our ideal new hometown would have inviting sidewalks with interesting stores and restaurants alongside, including independent bookstores, and and with larger cities nearby. We craved ethnic diversity and a variety of cuisines. Most of all it had to look and “feel right,” with a distinguished collection of high-style and vernacular architecture, gathered together in a human scale. A preservation-minded mayor, the late Vincent “Buddy” Cianci, with seemingly off-the-wall ideas, played an important promotional role. He and other local leaders weren’t afraid to help arrange for the likes of Venetian gondolas and to light up a river.

Note that there were no econometrics in our city-search template.

WaterFire was one of the urban inventions that impressed this city shopper.

— Sketch by William Morgan

Size is not really an accurate gauge of a city’s desirability – CNN Best Towns are actually smaller cities, from about 50,000 to about 225,000 residents. One interesting aspect of the story, however, is that it uses the term town. The word seems to suggest something more accessible than canyons of concrete and glass.

In Britain, the people who shape metropolises are called town planners. Before consolidation into Greater London following World War II, the British capital had been a collection of 23 boroughs, each with its own government, identity and traditions. One thinks of Providence’s two dozen neighborhoods, from Silver Lake to Fox Point, collectively contributing to a lively mosaic instead of an Anywhere USA blanket of sprawl.

Great towns need boldness and innovative out-of-the-box thinking. Providence uncovered a river and moved an interstate highway.

— Photo by William Morgan

Let’s stop worrying about lists and ratings and simply strengthen those attributes that make a place beloved – attributes that Providence has in spades. Economic development has a major role, of course, but stressing monetary concerns over humanizing factors cannot ensure a high quality of urban life. And worse than lists are one-size-fits-all advertising, such as the current slick but trite “All that …” campaign. If Providence is an urban success, people will come to visit those who live here and who have helped make it one the best towns anywhere.

People connecting make a lively town, not statistics. Hope Street is the main drag of Providence’s East Side.

— Photo by William Morgan

Architectural historian, critic and photographer William Morgan has lived in Providence for 25 years. His latest book is Academia: Collegiate Gothic Architecture in the United States.

William Morgan: Big bargains and major mysteries at Savers

Photos, except for the picture of the author himself, by William Morgan

Savers (“make secondhand, second nature”) is the largest for-profit thrift retailer in the country, serving 29 states. There are a half dozen Savers close to us in Rhode Island and Massachusetts that we frequent, but the one on Branch Avenue at Interstate 95 in Providence is the motherlode. Since we discovered Savers, I cannot remember buying an item of clothing anywhere else. Where else could I find a Harris tweed jacket from Edinburgh for $9.99 or a university scarf from a Glasgow department store that closed in 1943 for $3.99?

That said, I hate to shop. So, when my wife, Carolyn, is in Savers in search of fabric with which to make clothes, tchotchkes to incorporate in art, or household furnishings for young newlyweds, I roam the bookshelves there (or what we call The Library). Then with a couple of British murder mysteries (mystery reading is an addiction, said W.H. Auden, like smoking or alcohol), I head for a comfortable chair or sofa in the furniture section (which we call The Lounge), where I settle in for some reading and likely a nap.

The author reading in Savers.

— Photo by Gabs Chioniere

Sometimes a napping man causes a stir, and once someone asked if I were dead. Other times, I may head outside to get away from the pervasive used-clothes smell. There’s not much room around our Savers to walk safely; still, beyond the cigarette butts, dental-flossing devices, and candy wrappers, the parking lot can yield some treasures. A recent perambulation suggested that there’s darker side to Savers: unsolved mysteries.

Why the abandoned trousers? An after-hours tryst interrupted and the pants left behind?

A dismembered ear? Presumably a discarded part of a Halloween costume (Halloween is huge at Savers). Although, at first glance, there is a suggestion of violence, as with the blue jeans. Instead of behind a bar in Arles, a contemporary Van Gogh and Gauguin had a knife fight outside of the thrift store.

Most mysterious of all was a single high-heeled shoe abandoned at the edge of the Savers parking lot.

Was this pump left behind by a hasty Cinderella fleeing a wee hours ball held on the asphalt?

William Morgan is a Providence-based architectural writer. His latest book is Academia: Collegiate Gothic Architecture in the United States.

William Morgan: All that and nothing at all; how not to promote a state

The State of Rhode Island, beset by the self-inflicted woes of failing infrastructure, persistent corruption and a lack of self-confidence, has launched a new tourism initiative that it hopes will bring swarms of visitors to our shores this summer. “All That” is the campaign’s motto.

All That, period. What’s more banal than a lighthouse?

—Commerce Rhode Island

Despite its 1990s hip-hop vibe, the pandering of Rhode Island to potential visitors is clothed in familiar banal corporate-speak, accompanied by photographs of lighthouses and Newport mansions, with “All That” splashed across them.

There are videos showing young and happy revelers biking, surfing, dining – creepily identical to the branding firm’s clips on Belize, Park City, and other fun destinations–what you might expect from a Florida agency whose motto is “We make momentum happen’’.

Why does our culturally and geographically endowed Rhode Island need this everywhere -- and — everyone sanitized vision of itself?

Rhode Island is not the only state going through the periodic contortions of trying to sell themselves to mythical, profligate-spending hordes of tourists. Politicians are also easy marks for snake-oil salesmen of new images that they hope will appeal to the electorate.

(“All That”has apparently cost taxpayers half a million dollars, but queries through the Access to Public Records Act will no doubt reveal a much higher figure.)

Political appointments offer clues about the cluelessness of heads of state, so it should come as no surprise that Anika Kirble-Huntley, the chief marketing officer for Rhode Island Commerce, has spent her entire career in the casino industry.

Fun-Sized, perhaps, but what potential tourist would be enchanted by this murky and grim image?

—VisitRhodeIsland.com

“All That” is the fourth tourism re-brand fiasco in recent years. There was the embarrassing “Fun-Sized” campaign, and the slightly mysterious “Whatever you do …” The most infamous, however, was when Rhode Island hired design-great Milton Glaser to come up with the tepid slogan “Cooler and Warmer,” complete with a clip of alleged local skateboarders zipping along the harborside – in Reykjavik. Slightly less egregious was “Discover Beautiful Rhode Island,” whose chief legacy is handsome signs positioned at the state line.

A quiet sign exhorting Rhode Islanders to discover where we live; tourists on I-195 are in a rush to get to Cape Cod.

— Photo by William Morgan

Rhode Island, to which my wife and I moved to by choice twenty-five years ago, may be the smallest state by area, yet it boasts 400 miles of Atlantic shore, a rich 400-year history seen in an incredible array of outstanding architecture. We were enchanted by Rhode Island’s diversity, its food, its educational institutions, and its palpable tradition of independence and tolerance.

Content with Rhode Island, I do not envy any state its bigger size. But, at the other side of the continent, I am in awe of Alaska’s waving identifier. It is an impeccable and unimpeachable symbol, perhaps the best advertisement for any American government entity. There are no mottos, no Latin phrases, no animals, or any potentially controversial figures – just a tribute to the northern sky.

The blue field with the gold stars of the Big Dipper pointing to the North Star, is a simple, strong, and recognizable design that has served boldly for a century, from territory to 49th state. This powerful, no-nonsense banner, adopted in 1927, will look fresh in another hundred years. Part of the brilliance of the design lies in its genesis: the American Legion sponsored a competition among school students throughout the territory that brought forth 700 entries. The winner was Benny Benson, a Native Alaskan orphan. For his brilliant scheme Benson was given a gold watch and $1,000. As “All That” demonstrates, the price of re-branding has gone way up, and handsome civic design is mostly a thing of the past.

The flag of Alaska, designed almost a century ago.

Rhode Island would have been better served by giving the money spent on the advertisements to folks to enable them to host visitors. The people who run the state gravitate to bigger scams, such as pro-sports stadiums, movie studios, and dubious highway contracts. Citizens will never see much of this squandered money again, even though we will be underwriting it for decades. Nevertheless, it is time to stop wasting dollars on silly, meaningless, and dubiously ineffective tourism promotions. Like the Alaska flag, Rhode Island itself ought to be advertisement enough.

William Morgan is an architectural writer based in Providence. His latest book is Academia: Collegiate Gothic Architecture in the United States (Abbeville).

Going medieval

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal 24.com

In reading William Morgan’s brilliantly written and gorgeously illustrated new book, Academia – Collegiate Gothic Architecture in the United States, you might recall Winston Churchill’s famous line: “We shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us.’’

I thought of this looking back at an institution I attended, a then-all-boys boarding school in Connecticut called The Taft School, founded by Horace Taft, the brother of President William Howard Taft. Its mostly Collegiate Gothic buildings made some of us students feel we were in a hybrid of a medieval church and a fort. This, I think, encouraged a certain personal rigor and seriousness of purpose, amidst the usual adolescent cynicism and jokiness.

The blurb from the publisher (Abbeville Press) summarizes well the book:

"Academia provides the ultimate campus tour of Collegiate Gothic architecture across the United States, from Princeton and Yale to Duke and the University of Chicago. It tells the surprising story of how the Gothic style of Oxford {whose origins go back to 1096} and Cambridge {founded in 1209} was adapted and transformed in the United States, to lend an air of history to the country’s relatively young college and prep school campuses. And it shows how Collegiate Gothic architecture, which flourished between the Gilded Age and the Roaring Twenties {into the Thirties, too}, continues to define the popular image of the college campus today—and even inspire new construction.’’

The style originally reflected a certain Anglophilia embraced by some American nouveau riche as they accumulated fortunes in a rapidly expanding economy. Rich donors, and the institutional architects they got hired, wanted to create buildings evoking kind of elite, aristocratic culture at certain old Protestant colleges and universities and private boarding schools. (Many of the latter were modeled on English boarding schools catering to the aristocracy.) There was often a lot of snobbery involved. But the style spread to other institutions, too, including businesses and government offices, around the country.

Some of this included fantastical (to the point of silliness) ornamentation and instant aging of stonework to suggest the wear of centuries on what were brand-new buildings, perhaps most flamboyantly at Yale. Get out those gargoyles!

The nearest major Collegiate Gothic campus to Providence is the Jesuits’ beautiful Boston College in Chestnut Hill, just outside of Boston.

Some institutions mostly stuck with the simpler and cheaper Georgian brick style (in New England that includes even mega-rich Harvard and merely rich Dartmouth and Brown) but Collegiate Gothic was a huge thing for decades, and much of it was beautiful. Even today, architects are designing, sometimes ingeniously, new applications of the style.

This book is about much more than architecture. It’s also about personalities, many of them colorful, class, including social climbing, Western civilization, economics, materials, politics and many other things.

One of the book’s joys is Mr. Morgan’s footnotes, which besides adding to the understanding of the main text, are often very entertaining, sometimes even hilarious.

Gasson Hall, at Boston College, in the Chestnut Hill section of Newton, Mass., an example of high Collegiate Gothic architecture

— Photo by BCLicious

Massachusetts Hall at Harvard University, an example of the sort of Georgian Brick architecture that was the most common alternative on campuses to Collegiate Gothic.

Will Morgan: A mystery photo and missing memory

Half a dozen years ago, our current president published a book about his son’s death from glioblastoma. Titled Promise Me, Dad: A Year of Hope, Hardship, and Purpose, started with Beau Biden’s plea to his father not to let grief overcome him. (The loss of the Delaware senator’s wife and daughter in a car accident in 1972 almost derailed Biden’s life, including his political career.)

I found an autographed copy of the book, simply inscribed “Joe Biden,’’ in Savers in Boston’s West Roxbury for $4.49. The forgotten best seller did, nevertheless, offer a treasure, the mystery photo above.

There are almost no clues as to the identity of this young girl and, presumably, her younger brother. It’s printed on Kodak Xtralife II paper, but who uses prints in this age of computers and online libraries? The buildings look recent – faux Georgian – although the cobblestone street could be European.

Looking at the lass’s auburn hair and complexion, we could guess that these children are Irish.

There’s a story here, at least in our imaginations. But, promise me, Dad, that you will date your photos and tell us why images like this represent a memory worth keeping.

An architectural and photo historian, William Morgan is a frequent contributor to New England Diary. His latest book, Academia: Collegiate Gothic Architecture in the United States, will be published in October.

Downeast joys

Above, Treasures and Trash Barn in Sedgwick, Maine

Below, now closed lobster shack on Isle au Haut, an eatery once famous for its prize-winning lobster rolls.

— (The new!) photos by William Morgan

1908-1909 photos

Summer jump start

Photo by Willliam Morgan taken in Acushnet, Mass.

The Long Plain Museum, in Acushnet, was built in 1875 as the Long Plain School House. The school closed in 1972, and the building was then reopened as a local history museum, now operated by the Acushnet Historical Society.

The museum features four rooms focusing on the Acushnet whaling heritage, the blacksmith trade, period clothing and furniture, numerous other artifacts and a restored schoolroom.

The Long Plain is a local outwash glacial deposit of sand and gravel.

A downtown homeless person classically draped

— Photo and text by William Morgan

It’s 11 on a Saturday morning in downtown Providence, and someone is sleeping in. This stretch of Chapel Street between Grace Church and the Providence Performing Arts Center has two or three encampments, where building-entrance alcoves provide a modicum of shelter from the elements.

The sadness and embarrassment of homeless people, and the failure of a supposedly enlightened city to take care of its marginalized and less fortunate, tear at one’s heartstrings.

Whatever the issues around social conscience and civic breakdown, some credit is due to this intrepid street denizen. He or she is wrapped in an ecclesiastical purple blanket, like a giant burqa without eye holes. The draping of the fabric recalls classical Greek statuary, such as the Elgin Marbles, from The Parthenon.

As I passed, from a tent pitched in the next entryway, a female voice wafted out, “Have a nice day.’’

William Morgan is an architecture writer and historian based in Providence. His latest book, Academia: Collegiate Gothic Architecture in the United States, will be published in October.

Grandeur or at least mystery at Good Fortune

— Photo and text by William Morgan

At a time when most public art is too realistic, too political, and just too awful, it can be a pleasure to stumble upon some unplanned artistic achievement– art in spite of itself.

This urinal in Good Fortune, the giant warehouse of Asian food in the Elmwood section of Providence, offers humor, dignity, and an appropriate aura of mystery befitting an intriguing work of art.

This plumbing fixture is broken, but the sign, “Operation Suspended,’’ hints at grander exploits, such as the cancellation of a moon shot or an aborted Navy Seals raid.

Set off by faux marble and black poly-something-or-other, the flushing mechanism takes on the look of a sleek, abstract chromium sculpture – a tribute to American industrialization, perhaps. A dismembered torso, or perhaps a tuxedo on a coat hanger, lurks beneath the shiny, elegant, mink-coat-black drape.

High fashion or a postponed plumbing repair?

William Morgan is a Providence-based writer and architectural historian. He holds a Ph.D. in American Art from the Bidens’ alma mater, the University of Delaware. His latest book, Academia: Collegiate Gothic Architecture in the United States, will be published this fall.

#art #Providence

Homeless and classically draped

Photo and text by William Morgan

It’s 11 on a Saturday morning in downtown Providence, and someone is sleeping in. This stretch of Chapel Street between Grace Church and the Providence Performing Arts Center has two or three encampments, where building-entrance alcoves provide a modicum of shelter from the elements.

The sadness and embarrassment of homeless people, and the failure of a supposedly enlightened city to take care of its marginalized and less fortunate, tear at one’s heartstrings.

Whatever the issues around social conscience and civic breakdown, some credit is due to this intrepid street denizen. He or she is wrapped in an ecclesiastical purple blanket, like a giant burqa without eye holes. The draping of the fabric recalls classical Greek statuary, such as the Elgin Marbles, from The Parthenon.

As I passed, from a tent pitched in the next entryway, a female voice wafted out, “Have a nice day.’’

William Morgan is an architecture writer and historian based in Providence. His latest book, Academia: Collegiate Gothic Architecture in the United States, will be published in October.

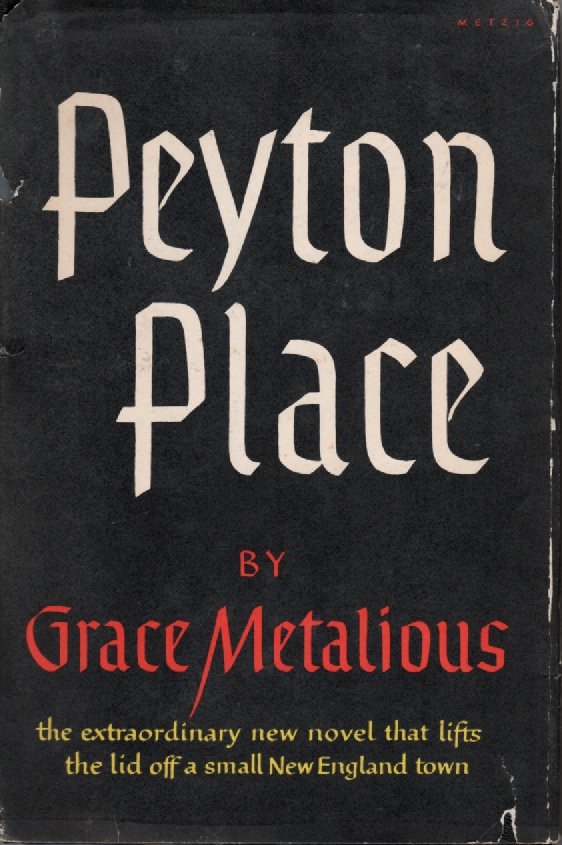

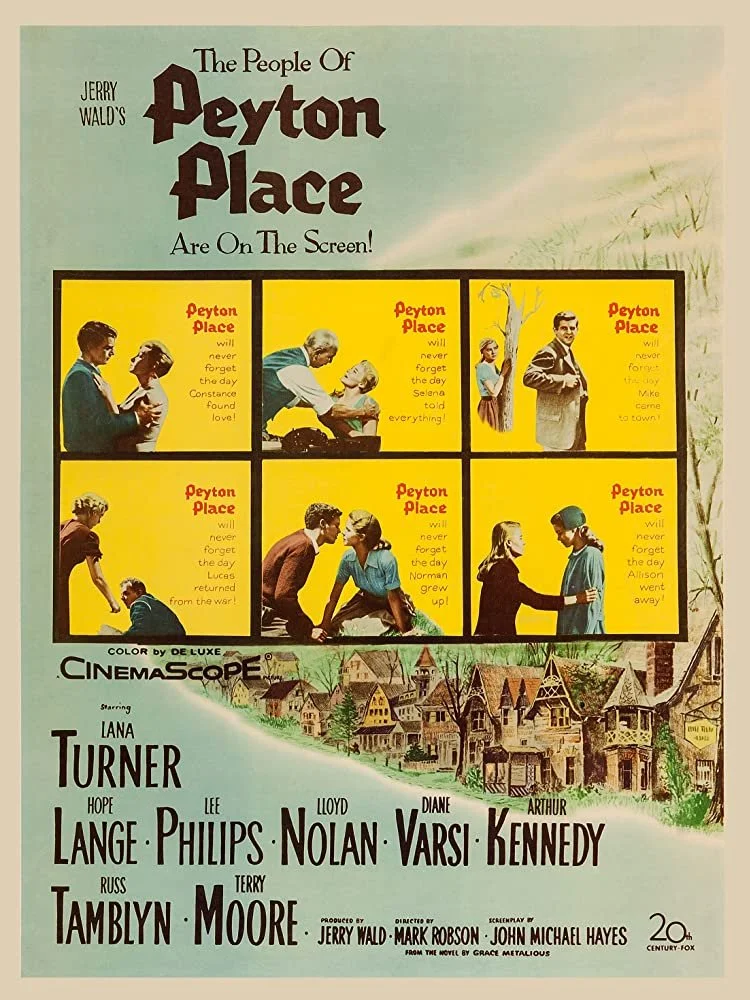

Take a left for scandal

In New Hampshire’s Lakes Region: G.I.W. refers to the village of Gilmanton Iron Works, in Gilmanton, the model for Peyton Place, the town in the once scandalous 1956 novel of the same name by Grace Metalious. Gilmanton Irons Works is named for a long-gone unprofitable mining operation.

— Photo by William Morgan

In Gilmanton: Iron Works Bridge in 1910.

Existential confusion

Inside Greg’s Famous Seafood, in Fairhaven, Mass.

— Photo by William Morgan

William Morgan: Where obscurity may have helped save some of a town’s beauty

Photos by William Morgan

The signpost on the green in Rochester, Mass., tells you how far you are from various Bay State towns. The attractive, old-fashioned marker also hints that this place is the back of beyond — the middle of nowhere.

Rochester wasn’t always a place forgotten. First settled in 1679, it was a major shipbuilding town, at least until what became Marion and Mattapoisett broke away and Rochester became landlocked.

There are a few handsome Federal period houses dotted about the countryside, no doubt remnants of maritime wealth before New England commerce was strangled by Jefferson’s Embargo Act of 1807.

Rochester’s town common boasts a marvelous Carpenter’s Gothic church. The church’s foundation goes back to 1703, but this confection dates to the middle of the 19th Century. The First Congregational Church’s medievalism is a riff on the typical New England Meeting House: a simple preaching box with a battlemented tower instead of a multi-tiered Georgian steeple.

There are no great masonry walls or expanses of stained glass. The meeting house windows have pointed tops, the tower base has louvered openings in the shape of quatrefoils, and the corners of the parapets have spikey caps

The delightful First Congo is not going to make up for the loss of access to Buzzards Bay. But the town’s very misfortune may have preserved this treasure.

William Morgan is a Providence-based architectural critic and historian and photographer. He is the author of American Country Churches and The Cape Cod Cottage, among other books.

Poor Rochester (in red) — so near Buzzards Bay but cut off. Orange is Plymouth County.

Warming up nostalgia

Summer afternoon shadow and sun in Acushnet, on the Massachusetts South Coast.

— Photo by William Morgan

William Morgan: Less is more at RIC nursing-school building

At Rhode Island College, in the Mount Pleasant section of Providence.

— Photos by William Morgan

The home of the recently named Zvart Ononian School of Nursing at Rhode Island College is a handsome and noteworthy addition to the architectural scene in Providence. Not unlike the public-education sector that built it, and the nursing profession itself, the 12,000-square-foot facility is modest, accomplished and without pretense.

Since its beginning, in 1970, RIC’s nursing program has been in the Fogarty Life Sciences Building. In recent years it has been desperately in need of additional space. And an important need has been to establish a visual identity for the School of Nursing. Fogarty, to which the Ononian is attached, is typical of so many of the buildings at RIC: buff brick functionalism that proclaims its post-World War II public university aura.

The School of Nursing’s building went up six years ago, but received little notice until the school received $3 million this year in honor of licensed practical nurse Zvart Ononian

Rhode Island College moved out from downtown Providence to 180 acres of rolling Mount Pleasant landscape in 1958, but the countryside remained about the only thing that distinguished the campus. Its scattering of two-story, flat-roofed classroom buildings appeared like a combination of parochial high school and Midwestern agricultural college. (The style, no doubt, reflected economic reality as much as any philosophy of architects Howe, Prout & Ekman.) RIC’s architectural image started to look up with the construction of the John Nazarian Center for the Performing Arts, in 2000. The theater, designed by William Warner, a prime mover in the Providence Renaissance, has been joined by the sleek, copper-sheathed Alex + Ani Hall, by the respected Boston architects Schwartz/Silver

The Art classroom building at RIC, Alex + Ani Hall.

Unlike the art building’s stylistic variation on the theme of the earlier campus structures, the School of Nursing’s single-pitched, sloping roof creates a subtler, less institutional approach. And, instead of two stories squished together, the new building offers a high and welcoming gathering space, bathed in light from full-height windows. Gathered around this spacious hall are administrative offices, meeting rooms and simulation laboratories for hands-on training.

Inside the nursing school.

JMT Architecture, designers of the nursing school addition, have 1,600 employees, with offices in Baltimore, Philadelphia and Cleveland. While no one would confuse JMT with famous starchitects, or a small studio firm, they run a highly successful commercial enterprise that delivers dependable workmanlike buildings to satisfied clients. The RIC Nursing School doesn’t knock one’s socks off with architectural pyrotechnics, but it does not look money-starved, as publicly funded school design often does.

Entrance to Ononian School of Nursing. Thoughtful use of inexpensive materials.

The curtain wall mullions could be a little more sophisticatedly detailed, and the boxy entry vestibule is a little awkward. But the laminated timber implies strength; the entire materials palette, especially the concrete plank covering, complements the wood framing. This is a gentle, sensibly proportioned building that does not try too hard. The most appealing aspect of the school of nursing is perhaps the landscaping, where river birches set amidst natural grasses contribute a pastoral Scandinavian ambience.

Entrance to Ononian School of Nursing. Thoughtful use of inexpensive materials.

Administrators and the simulation-lab coordinator who spoke with GoLocal had only positive things to say about the nursing school building. The idea that appealing architectural design would attract students did not seem to be a consideration. Rather, it is the desire to offer an affordable nursing degree that matters. Even if the relationship of good design to academic success is unarticulated, the nursing facility is a happy place to teach and learn, as well as the attractive face of the school.

And compared to the silliness of expensive and inappropriate architectural statements, such as the fatuous RISD student center or Brown’s Performing Arts fiasco, the Zvart Ononian School of Nursing at Rhode Island is a welcome grace note.

Architecture writer and historian William Morgan is the author of a number of books about campus architecture, including Collegiate Gothic (Universty 0f Missouri Press) and The Almighty Wall (MIT Press).

William Morgan: Save downtown Providence's centerpiece

The Industrial Trust Co. building is the fulcrum of the Providence skyline.

— Photo by David I. Jacobson

Saving and rehabbing the Industrial Trust Co. Building is crucial to revitalizing downtown Providence. To imagine the city without the nicknamed “Superman Building,’’ is like contemplating Paris without the Eiffel Tower or London without Big Ben, New York without the Empire State Building or Washington without the Capitol.

Most of the recent discussion of saving the skyscraper, designed by the New York firm of Walker & Gillette and built in 1928, has been about the cost of restoration and who should bear that hefty multimillion-dollar expense. While no small matter, the real issue about preserving and rehabbing Providence’s most prominent urban symbol cannot hinge just on the money. Losing this landmark would be a disaster, one that would cost the city and state immeasurably more than bonded indebtedness or taxpayer pain. It would mean a loss of prestige, optimism, self-confidence and our well-earned reputation as a Renaissance City.

Aerial view of downtown Providence shows keystone position of Industrial Trust Building.

— Photo by Luis Carranza

The limestone-sheathed Art Deco masterpiece at 55 Kennedy Plaza is simply a landmark that we must not lose. More than any other element of the skyline, with the exception of the State House, the Industrial Trust Building is the identifiable icon of the city.

Not just the tallest, but the most attractive element of the downtown skyline.

— Photo by William Morgan

There are significant architectural and historical considerations that favor preservation, not to mention the benefits of an infusion of new downtown inhabitants. Yet, the key role that the Superman Building plays is as a majestic visual fulcrum – a clearly recognized feature, a compass marker, an urban punctuation point much like the Eiffel Tower.

Eye appeal: lantern detail of the top of the building, designed, among other things, to be a port for dirigibles.

— Photo by William Morgan

Unlike a lot of its newer neighbors, the Industrial Trust Building is an artfully decorated architectural masterpiece, and not a boringly repetitious wall of undifferentiated glass. Not just vertical real estate, its mass diminishes as it reaches for the sky–the work of architects who understood beauty, good proportions, scale and civic aspiration.

Compare the Superman Building with the 1973 addition to the Hospital Trust Tower, an uninspiring lump of travertine; in half a century the quality of downtown commercial architecture declined visibly.

— Photo by William Morgan

It is irresponsible to declare that the Industrial Trust Building will be razed if the current financing package cannot be agreed upon: this is a structure for which a use and renovation plan must be found. There is no alternative. As Robert Whitcomb argued recently in GoLocal, tearing down this noble identifier and symbol of the city’s once great commercial prowess would send a terrible message to the world. If we cannot afford to restore this treasure, how likely would we be able to fill in the void left by its destruction? Or as one of my urban-planning mentors, Congressman Charles Farnsley, a sponsor of the 1966 Historic Preservation Act, used to say of such urban mauling: This is like a beautiful woman losing a front tooth in a country with no dentists.

Charles Farnsley, mayor of Louisville, Ky., before working with Lyndon Johnson on preservation, had another phrase that is even more haunting: Americans are the only people who bomb their own cities. In a town known as a preservation success story, that’s not a mantle we should want to wear. Rather, we need to be the city that opened the rivers, removed an interstate highway slicing through its heart, and created a vibrant arts scene. If we can do that, we can figure a way to breathe new life into the Industrial Trust Building.

Providence skyline without the Industrial Trust Building.

— Photo by William Morgan

William Morgan is the architecture critic of GoLocalProv.com, as well as a long-time contributor to New England Diary. He’s the author of many books on architecture.

William Morgan: Paying homage to a young Maine hero

— Photo by William Morgan

Pine Grove Cemetery, in Appleton, Maine, is not easy to find. This rural community beyond the Camden Hills has a post office, a library and a fast-running stream where a mill once stood; the town office is open only three days a week. An elementary school serves the town, but middle and high- school students must travel by bus to Camden.

My wife and I drove down a road with an Abenaki name and across the Saint George River, up a steep hill to a ridge, in search of a barely marked turnoff. We bumped along a rutted dirt track to one of those ancient New England burying grounds with slate steles carved with primitive angels.

The grave we searched for was not under the elegiac oaks and dark conifers, but in the new part. This half of the cemetery has few trees, and the gravestones tend to be more elaborate, colored and polished. Many are adorned with plastic flowers, teddy bears and other tributes of contemporary mourning. The vertical marble slab we were visiting had not been tended in a while. Veterans of Vietnam and the Persian Gulf rest nearby.

On Feb. 26, 2006, Joshua Humble, a specialist in the famed winter warriors of the 10th Mountain Division, was killed near Baghdad by a roadside bomb – the 2,385th U.S. soldier to die in Iraq. Humble had just turned 21. A regimental honor guard stood by his coffin at a funeral home in Belfast, then followed the hearse to Appleton for burial.

Thousands of kids died in the Iraq War. What was so special about one from an agricultural community in Maine? Was he like so many soldiers: high school, limited local prospects and maybe a desire to get away from small-town life?

A newspaper obituary shows a face of aching innocence. His middle initial was intriguing: Did the “U.” stand for Ulysses, Uriah or maybe Uncas? His stone revealed that the U. was for Ut, an Asian anomaly in an all-white Appleton.

Josh Humble is remembered primarily through an ongoing memorial on Legacy.com. There have been 47 comments since Humble’s death, most from buddies in arms who speak of his heroism. Five years ago, Julie Lee, from the Maine town of Washington, recalled Josh as “a respectful kid with a fun sense of humor.” She added, “Your sacrifice for our country will not be forgotten.”

Yet recent war deaths such as Humble’s have been forgotten – only an average of three notes a year on an obituary, and memorial Web site is not much of a remembrance. These are the young men and women of a volunteer military who carried the load while the rest of us did not face roadside bombs in the desert.

I was drafted in 1966 but was determined not to be sent to Vietnam. After passing my Army physical, I implored an orthopedic surgeon – my college roommate’s father – to write a letter outlining how a skiing injury would make me unfit for basic training. Contemporaries who did not have such connections went to Southeast Asia, and of course some died there. Maybe unforgetting one Maine soldier would offset the shadow of my not having donned a uniform.

Since reading of Josh Humble’s death 15 years ago, we had talked of paying our respects at his final resting place. It was a bucolic, almost secret, graveyard on a perfect autumn day. I was glad we went. But as I placed a stone on Josh’s marker, I did not feel peace or closure. Instead, I was overcome by a rage that took me back to the protests of my youth. For me, Joshua Humble symbolizes the tragedy of nonsensical wars that robbed hundreds of places like Appleton of their young people and their future.

William Morgan is an architectural writer and a resident of Providence who has taught at Princeton University, the University of Louisville and Brown University, among other institutions. He went to camp in Litchfield, Maine, in the 1950s.

Camden, Maine, near Appleton, viewed from the summit of Mt. Battie, one of the Camden Hills.

— Photo by Dudesleeper

William Morgan: A medical firm’s lost design opportunity in a very dramatic spot

When can a substandard commercial building be transformed into good architecture? Can a despised icon of second-rate design become a beloved object? More specifically, can the ugly behemoth of University Orthopedics, in East Providence, R.I., overcome the stigma of being just another spec medical box?

University Orthopedics, 1 Kettle Point, East Providence, N/E/M/D Architects.

Photo by William Morgan

Kettle Point, which is also the site of a development of the kind of suburban housing seen near urban interstates everywhere, is a gorgeous promontory with unparalleled views of the Providence skyline, a working waterfront and down Narragansett Bay. If this site were not in the perceived ugly step-sister of East Providence, it would have been one of the most desirable pieces of land in the state. One thinks of what will happen to the neighboring Metacomet Golf Club course, glorious open land with tremendous potential: It will turn into the all-too-familiar faux-Colonial tackiness on a sea of asphalt.

Kettle Point housing development.

— Photo by Will Morgan

On the positive side, University Orthopedics is affiliated with Brown University’s Warren Alpert Medical School and so is one of the parts of Providence’s growing importance as a medical center. And the Kettle Point location offers expansive and maybe healing views of water, trees and skyline. This giant infusion of sunlight and a panorama of nature must surely contribute to the wellness of the patients and the happiness of the staff.

Providence harbor and downtown skyline from Kettle Point.

— Photo by William Morgan

The ugly duckling becomes a swan when a loved one needs treatment for osteoporosis or a broken limb. Then the state-of-the-art facilities and the staff’s training seem more important than aesthetics. But do they need to be mutually exclusive? What if the medical group that commissioned 1 Kettle Point had hired someone besides a value-engineering-minded developer? At the very least, a location this visible demanded a better design than a clunky real-estate container wrapped in cheap materials, one that looks like every other new medical office block from Boise to Little Rock.

Does this signage or the Home Depot-orange cladding symbolize quality medicine and research?

— Photo by William Morgan

A sensitive architect might have at least given 1 Kettle Point a more distinctive skyline. (Please do not whine that a good architect costs too much, as a really smart designer might have even given University Orthopedics a lot more for less.) And given such an environmentally sensitive site, a landscape architect should have been consulted, and maybe allowed to integrate this hulk into its prime surroundings.

Alas, the response in our high-quality (for those who can access it) but often unobtainable, fragmented and even chaotic American health-care system to such concerns is always one of money. What a building looks like seems minor compared to the medicine it delivers. But why not heal the entire patient, while at the same time supporting a quality building that could have been a great advertisement for the practice, for Brown, for Rhode Island?

The handsome lights on the stair compliment the undoubtedly unintentional industrial aesthetic of the metal railings.

— Photo by Will Morgan

Hospital needs, admittedly, dictate their forms. Think of all the university-affiliated and other medical centers that keep spreading across America, with new wings and additions, often in disparate styles. Yet, a handsome example that exists within the jumble of buildings that comprise the main campus of the august Massachusetts General Hospital, in Boston, is the handsome neoclassical original building, designed by Charles Bulfinch. In erecting their signature structure, the hospital trustees chose the architect of both the Massachusetts State House and the U.S. Capitol.

Massachusetts General Hospital, Charles Bulfinch, architect, 1818-23. Wikimedia Commons.

My favorite example of a successful hospital that is also a work of architecture is a tuberculosis sanatorium in rural Finland, designed in 1929 by a then-young Alvar Aalto. Built with limited resources, the sanatorium launched Aalto’s career, but it also became one of the noblest landmarks of modern architecture. The revolutionary aspects of the design were dictated by the treatment of TB, which emphasized abundant sunlight and fresh air. Aalto fashioned draft-less windows and splash-less sinks, along with bright colors and inexpensive furniture that is still being manufactured.

Tuberculosis sanatorium, Paimio, Finland, 1929-33.

— Photo by the Alvar Aalto Foundation.

Why should what University Orthopedics looks like, and how it contributes to or detracts from its environment, be any less important than the layout of its labs and operating rooms? This medical group, presumably, would not accept low professional standards of medicine. So, it is unfortunate that, in the quest for medical integrity, University Orthopedics’ patronage did not aspire to high standards of architectural design

William Morgan has taught the history of modern architecture at several colleges, including Princeton and Roger Williams Universities, and has written extensively on Finnish architecture.