Saving the ‘little things that run the world’

— Diagram by YJaredY

Text excerpted from an ecoRI News article

KINGSTON, R.I. — Steven Alm and Casey Johnson in the University of Rhode Island Bee Lab want property owners to think small. Though tiny, the issues the duo is examining are anything but trivial. In fact, the issues they are studying are bellwethers for larger issues facing the natural world.

They want to reminding us of the importance of, as E.O. Wilson said, “the little things that run the world.”

A professor at URI and keeper of the university’s Insect Collection, which dates to the late 1800s, Alm is concerned about the insect loss he has witnessed in the course of his career, never mind the species that now only exist in pinned specimen form, no longer in the wild.

“We’re in trouble with the insects,” he said. Birds, fish, and other members of the food web need insects, but their numbers are dwindling. Pollinators in particular are vulnerable.

To read the whole article, please hit this link.

Land conservation has favored the white and wealthy

In Westport, Mass., where affluent summer and year-round homeowners have helped protect much countryside from development.

From article in ecoRI News (ecori.org) by Frank Carini

Concern about environmental and social injustices is spreading, but little research documents how the benefits of land conservation are distributed among different groups of people. In fact, the findings of a new study reveal efforts are likely needed to account for human inequities while continuing land conservation needed for ecological reasons.

Protecting open space from development increases the value of surrounding homes, but a disproportionate amount of that newly generated wealth goes to high-income white households, according to the study published recently in the Proceedings for the National Academy of Sciences.

Land conservation projects do more than preserve open space, ecosystems, and wildlife habitat. These preservation projects can also boost property values for nearby homeowners, and those financial benefits are unequally distributed among demographic groups in the United States.

The study, by researchers from the University of Rhode Island and University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, found that new housing wealth associated with land conservation goes disproportionately to people who are wealthy and white.

To read the whole article, please hit this link.

#land conservation

Frank Carini: Turtles threatened by local poachers with global ties

A Spotted Turtle.

An Eastern Box Turtle.

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

Rhode Island’s reptiles and amphibians face pressure from numerous threats, and for many species, removal of even a single adult from the wild can lead to local extinction, according to the state’s herpetologist.

Since the local and/or regional future for many of these species — eastern spadefoot toad, northern leopard frog, northern diamondback terrapin, to name just a few — is in doubt, removing them from nature to keep as a pet or to sell is against the law. It’s illegal to sell, purchase, or own/possess native species in any context, even if acquired through a pet store or online, according to Rhode Island law.

Turtles are especially vulnerable, according to Scott Buchanan, who became the state’s first full-time herpetologist in 2018, because some species must reproduce for their entire lives to ensure just one hatchling survives to adulthood. The Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (DEM) staffer said it takes years, sometimes a decade or more, for turtles to reach reproductive age, if they make it at all.

Buchanan recently told ecoRI News that “broadly, across taxa” the illegal taking, or poaching, of wildlife is a “huge issue.”

“Globally, it’s considered one of the driving forces of population declines and even extinctions,” he said.

Wildlife trade experts and conservation biologists such as Buchanan point to poaching — driven by demand in Asia, Europe, and the Unified States — as a contributing factor in the global decline of some freshwater turtles and tortoises.

Tortoises and turtles grow slowly, mature late, and can, if given the chance, live for decades. This slow and steady lifestyle served them well for millions of years, but now, in the face of growing human pressures, it has become a liability.

Of the 360 known turtle and tortoise species, 52 percent are threatened, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List of Threatened Species.

A group of global turtle and tortoise experts published a 2020 paper that noted “more than half of the 360 living species [187] and 482 total taxa (species and subspecies combined) are threatened with extinction. This places chelonians [turtles, terrapins, and tortoises] among the groups with the highest extinction risk of any sizaeble vertebrate group.”

Turtle populations are “declining rapidly” because of habitat loss, consumption by humans for food and traditional medicines, and collection for the international pet trade, according to the paper’s authors. Many could go extinct this century.

Buchanan’s involvement in dealing with the impact of poachers is primarily around North American turtles. He noted turtle diversity is high globally and in the eastern United States — in the Southeast more than the Northeast, however.

But state and federal law enforcement officials and wildlife biologists consider the illegal collection of turtles to be a conservation crisis occurring at an international scale, according to Buchanan, who is the co-chair of the Collaborative to Combat the Illegal Trade in Turtles (CCITT), formed in 2018 within Partners in Amphibian and Reptile Conservation.

In the past four years, CCITT, an organization of mostly state, federal and tribal biologists, has documented some 30 major smuggling cases in 15 states. Some involved a few dozen turtles, and others several thousand.

In Rhode Island, Buchanan said there are four turtle species of concern: the eastern box turtle; the spotted turtle; the wood turtle; and the northern diamondback terrapin.

Eastern Box (species of greatest conservation need): This turtle spends most of its time on land rather than in the water. They favor open woodlands, but can be found in floodplains, near vernal pools, ponds, streams, marshy meadows, and pastures. They reach sexual maturity by about 10 years of age. Females nest in June and lay an average of five eggs in open areas with sandy or loamy soil. Eggs hatch in late summer.

Spotted (species of greatest conservation need): These turtles are sensitive to disturbance. They are usually found in shallow, well-vegetated wetland habitats, such as vernal pools, marshes, swamps, bogs, and fens. They reach sexual maturity at 7-10 years of age. Females lay an average of four eggs in moist Sphagnum moss, grass tussocks, hummocks, or loamy soil. Females probably do not lay eggs more than once a season, and females do not lay eggs every year.

Wood (species of greatest conservation need): For part of the year they live in streams, slow rivers, shoreline habitats, and vernal pools, but in the summer they roam widely across terrestrial landscapes. They reach sexual maturity around 10. During late spring, one clutch of 4-12 eggs is typically laid in nesting sites consisting of sandy soil or gravel. Eggs hatch in late summer and the young move to water.

Northern Diamondback (state endangered): Their population has suffered greatly due to poaching and habitat loss. They are found in estuaries, coves, barrier beaches, tidal flats, and coastal marshes. They spend the day feeding and basking in the sun and bury themselves in the mud at night. They reach sexual maturity at about six years old. Females lay a clutch consisting of 4-18 eggs. Some females will lay more than one clutch in a season and hatching usually occurs in late August. The young spend the earlier years of life under tidal wrack (seaweed) and are rarely observed.

All four are high-demand species in the pet trade, according to Buchanan.

“There’s a lot of illegal collection that takes place all throughout the eastern United States, including in New England and Rhode Island,” he said. “There’s a lot of recent cases that involve hundreds and thousands of turtles from those species illegally collected from individual populations, which is just totally unsustainable and has an immediate and lasting impact on those populations.”

Other turtle species that can be found in Rhode Island include eastern painted, common snapping turtle, and eastern musk.

“We have a lot of turtles for a small state,” Buchanan said. “They’re a conservation priority because of their life history. They’re just inherently vulnerable to population declines.”

Most turtles fall victim to predators before they mature. Rhode Island’s turtles are also threatened by habitat loss and fragmentation and by car strikes when crossing roads to breeding grounds.

Poaching is just another human-caused threat to their existence.

The 16 eastern musk turtle hatchlings confiscated by Rhode Island environmental police from a West Warwick resident in September. (DEM)

In late September environmental police officers from DEM’s Division of Law Enforcement found 16 Eastern Musk Turtle hatchlings, a species native to Rhode Island and the eastern United States, in the home of a West Warwick man suspected of illegally advertising them for sale on Craigslist and Facebook.

The case resulted from a week-long investigation, during which the suspect offered two hatchlings to undercover environmental police officers for purchase, according to DEM.

The suspect was charged with 16 counts of possession of a protected reptile or amphibian without a permit. The turtles were taken to the Roger Williams Park Zoo, which has a room and equipment dedicated to the care of turtles seized from the illegal turtle trade. The turtles will be released back into the wild after clearing health screenings and disease testing, according to DEM.

The 16 turtles are still at the zoo and “doing well,” according to Buchanan. He said only a minority of turtles rescued from poachers are returned to the wild, because of concerns about disease and, more importantly, not being able to determine the area from which they were taken.

The man has claimed the hatchlings were raised in captivity, but state officials believe the parents were likely taken from the wild and that the case also involves actions taken in another state. The case remains under investigation.

Last November, at New York City’s John F. Kennedy International Airport, about 100 eastern box turtles were found confined in socks inside an illegal shipment to Asia. A deadly ranavirus outbreak among the turtles confiscated by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service highlighted the risks and cruelty of the illegal wildlife trade, according to the New England Aquarium.

Smuggled turtles are often wrapped tightly in socks to keep them from moving. (USFWS)

Federal wildlife officials discovered the wildlife smugglers put multiple turtles, taken illegally from the wild, together into one box without food or water. Found hidden inside falsely labeled boxes, each turtle had been stuffed inside a tight sock to prevent it from moving.

The New England Aquarium took in many of the turtles and enlisted Zoo New England and Roger Williams Park Zoo to assist with treating the animals that were in poor health, suffering from dehydration and eye infections.

Buchanan said the global demand for box turtles has surged during the past few years.

A Chinese national was sentenced last year to 38 months in prison and fined $10,000 for money laundering after previously pleading guilty to financing a nationwide smuggling ring that sent 1,500 turtles worth nearly $2.3 million from the United States to China. The man used PayPal, credit cards, and bank transfers to buy the turtles from U.S. buyers advertising them on social media and reptile websites and sold them to Hong Kong reptile markets.

He trafficked in five turtle species, including the Eastern Box Turtle, protected by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora treaty.

Turtles, especially freshwater species, are among the world’s most trafficked animals, because, as Buchanan noted, reptiles can be kept in “explicitly inhumane conditions” — say, a sock inside a cardboard box — for a significant period of time.

“Enough of them survive to make it economical [for the criminal enterprise],” said Buchanan, noting most amphibians are too fragile to keep alive for that long.

Criminal networks connect with buyers who then sell the turtles as pets, to collectors, and to commercial breeders. Some species are coveted for their colorful shells or unusual appearance. In many countries, this illegal trade is either poorly regulated or unregulated.

To help protect Rhode Island’s native species, you can submit observations of amphibians and reptiles to DEM scientists online.

“Remember never to share turtle locations online,” according to DEM. “It can be exciting to see turtles in the wild, and to share your discovery. But before you take a photo of a turtle in the wild, turn off the geolocation on your phone. If you post a turtle photo on social media, don’t include information about where you found it. Poachers use location information to target sites.”

There are a few reptiles and amphibians that can hunted legally in Rhode Island: snapping turtles, bullfrogs, and green frogs. A current fishing, hunting, or trapping license is required and hunting/trapping must be conducted in compliance with season and size regulations. All animals harvested must be killed immediately following capture, as possession of live turtles or frogs is illegal.

Turtle traps must be marked with the trapper’s name and address, checked every 24 hours, and set in a manner that will allow turtles access to air, according to DEM. All bycatch must be released immediately at the location where the trap was set.

“This illegal collection of turtles … I think most people have a perception that it’s disparate or kind of small-time … it’s just some yahoos out there collecting a few turtles, when in fact it’s perfectly accurate to say the norm is international criminal syndicates that are driving the trade in turtles that leads to the illegal collection here in the U.S.,” Buchanan said. “There’s often times a local collector who’s in contact with a middleman who’s in contact with a criminal network that’s also involved in things like drug trafficking and human trafficking.”

Note: The sexual maturity and nesting habits of the four turtle species of concern in Rhode Island are based on their life and conditions here. For more information about the turtles of Rhode Island, click here. To watch a short U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service video about the importance of turtles and the threat from poaching, click here.

Frank Carini is co-founder and senior reporter for ecoRI News.

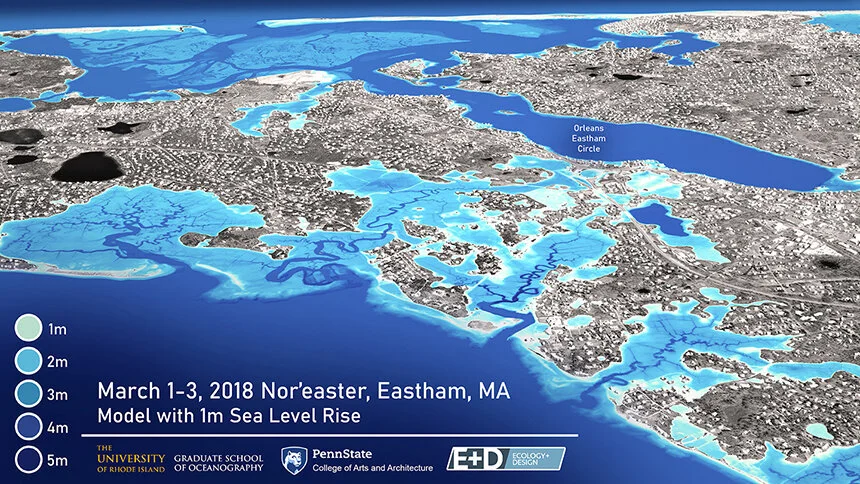

Study to look at relationship of sea-level rise and flooding in hurricanes and nor’easters

Realistic 3D visualization for Eastham, Mass., along the Cape Cod National Seashore using advanced modeling results of a March 2018 nor'easter with 3 feet of sea-level rise

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

KINGSTON, R.I. — Researchers at the University of Rhode Island and Pennsylvania State University were recently awarded a four-year, $1.5 million grant through the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to study the effects of sea-level rise and how it may exacerbate the impact of extreme weather.

The project will draw on expertise from researchers at URI’s Graduate School of Oceanography, its College of the Environment and Life Sciences, the Department of Ocean Engineering, and the URI Coastal Resources Center.

Other collaborative participants include the Schoodic Institute, in Maine, and the National Park Service. The goal of the project is to help communities, the National Park Service, and the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service adapt to a changing climate and more frequent and extreme weather.

The rate of sea-level rise is accelerating, according to NOAA. Since 1993, the average global sea level has increased by 3.4 inches. Sea level plays a role in flooding, shoreline erosion and other hazards, impacting nearly 40 percent of the U.S. population living in high-density coastal areas.

However, despite what is known about sea-level rise, there is a lack of research available when it comes to how the impacts of nor’easters and hurricanes may be amplified as a result.

“There are a number of studies that have been done looking at just sea-level rise or just extreme weather, but what we're really lacking in terms of clear understanding is the combined impact of these two phenomena,” said Isaac Ginis, a URI professor of oceanography who is leading the study. “This is especially important to us on the East Coast and in New England, where we’ve seen significant coastal flooding produced by waves and storm surge during nor’easters and hurricanes. How these effects are amplified by sea-level rise has been largely unexplored. This information gap inhibits our ability to properly plan for the future and is likely to lead to under-informed and ineffective adaptation measures.”

The project will expand the body of research related to the effects of extreme weather and sea-level rise on five New England national parks and two wildlife refuges — Cape Cod National Seashore, Boston Harbor Islands National Recreation Area and New Bedford Whaling National Historical Park, in Massachusetts; Ninigret National Wildlife Refuge, Trustom Pond National Wildlife Refuge and Roger Williams National Memorial, in Rhode Island; and Acadia National Park, in Maine, as well as their surrounding communities.

Using atmosphere, storm surge and wave/erosion modeling the team will provide high-resolution recreations of the impact of future storm and sea-level rise scenarios, identifying vulnerabilities in the ecosystems and infrastructure of the identified sites and their adjacent communities. The modeling will also include hazard, risk, and adaptability assessments, and mitigation scenarios.

Researchers will work closely with the National Park Service, U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, and stakeholders at the community level to tailor the research and translate the science in a way that can be incorporated into local resource management and adaptation measures to improve coastal resilience and to protect communities, people, infrastructure, and ecosystems.

“Each community has their own needs,” said Ginis, “but our modeling results will produce tailored and tangible information for local decision-makers — state and local governments, emergency management officials, town and city planners, and other stakeholders — to address their specific needs and enable them to plan and adapt as the sea-level rises and climate continues to change.”

Taking historical data into account, as well as topography, geology, water depth, land elevation, natural processes such as shoreline changes, and human influence, the team will be able to project more than 50 years into the future, using 3D visualization to provide computer simulations illustrating storm hazards and identifying potentially effective mitigation measures.

Ultimately, the project will open an important dialogue among researchers, local stakeholders, and federal resource managers, and facilitate the development of science-based best practices that will guide future policies and resource management strategies.

Caitlin Faulds: Sacred lotus joins other invasives to threaten waterways

A shroud of invasive sacred lotuses blocks in the edge of Meshanticut Pond, at Meshanticut State Park, in Cranston, R.I. Despite previous attempts to cull their growth, they came back in full force this year.

— Photo by Caitlin Faulds/ecoRI News photos)

Sacred lotus flower

Fr0m ecoRI News (ecori.org)

CRANSTON, R.I.

The pond looks like a painting. A small boat and a family of swans — two juveniles, two adults — marked by gentle wakes on a glassy surface. Early red leaves gracing the tops of periphery trees, late-season lotuses still framing from the edge.

But at Meshanticut Pond, there is a battle brewing on the water between the boat and sacred lotus.

In the past seven years, after a Cranston resident planted it in memory of a relative, the lotus — an invasive species, endemic to Asia and relatively new to Rhode Island waterways — has overtaken the pond. Just a few oversized leaves at first, now hordes of water lilies encroaching on three sides of the shore.

But according to Keith Gazaille, project manager with SOLitude Lake Management — a water-quality and waterbody-restoration company that works throughout the eastern United States — it’s not the only aquatic invasive crowding out native plants in the pond.

Gazaille and aquatic technician Tanner Poole are out on Meshanticut Pond on a stormy Tuesday morning to continue the fight against a trifecta of invasives: variable watermilfoil, fanwort and sacred lotus.

“The lotus and the other invasive plants have the ability to really outcompete a lot of the native plant species,” Gazaille said. “It really reduces the diversity of the habitat.”

It provides some habitat for fish and other aquatic life. But a dense canopy of invasives reduces the variability of the habitat, and it can wreak havoc on the levels of dissolved oxygen below the canopy. As the crowd of plants switches between oxygen production and respiration, large fluctuations in oxygen can be a stressor for aquatic life.

A team was out here last year, Gazaille said, trying to ward off the growth. But the invasives have stuck around, determined.

“The growth has gotten to the point where it has raised the attention of residents and the city,” Gazaille said. “And so, I think there was a request to take some action.”

Today, he and Poole will be boating over half the pond, spraying a contact herbicide below the water to try once again to stop the spreading milfoil and fanwort.

“There’s not a lot of good — given the expanse of the infestation — non-chemical strategies, unfortunately,” he said.

Harvesting and manual removal of both plants can be counterproductive, according to Gazaille. They reproduce by fragmentation, he said, “so as they potentially break during those activities, you could be worsening the situation, and potentially spreading plant fragments downstream.”

The best option, he said, is to spray a contact herbicide on the vegetative portion of the plant. It is best to do this in the early fall, before they enter a natural stage of auto-fragmentation. Eliminating them now reduces the risk of downstream infestation. The treatment will leave the root intact, Gazaille said, but through repetitive treatment there can be a slow reduction in growth density.

“The lotus is another animal altogether,” Gazaille said.

They had hoped to spray its protruding leaves, too, with a systemic herbicide. That would spread through the plant, “kill the rhizome and prevent return of the plants all year,” he said.

But the impending rain would wash the chemicals off too early. They need 3-6 clear hours for it to be effective. They’ll be back in the next few weeks to finish off the other half of the pond and deal with the lotuses.

A late-season crowd of sacred lotuses and clouds of algae overtake swath of Meshanticut Pond.

Compared to some areas of the South, where the growing season is unimpeded by freezing temperatures, Gazaille has seen lotus completely overtake a water system. But for the Northeast, he said that Meshanticut Pond is dealing with a moderate- to high-level infestation.

They are trying to stop it there, but “the sacred lotus has been particularly hard to kill,” according to Christine Dudley, the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management’s deputy chief of freshwater and diadromous fisheries.

And beyond Meshanticut, the battle against invasives is only getting worse.

“All over the world, really, but all over New England ponds are getting more and more infestations of invasives and more and more heavy algae and weed growth,” Dudley said.

There are a lot of different factors to blame. Usage around ponds has changed over the years, many have gotten more and more built up. Rising temperatures, eutrophication, lawn chemical use, released aquarium species, urban growth, and overburdened and leaching cesspools all play a role.

“It’s very difficult to tell someone that they can’t have a nice yard, or have a bigger house or a nicer house on a lake,” Dudley said. “But they really have to look to what’s happened over the years that has changed.”

There is legislation in the works to stop the sale of aquatic invasive species, but the reality on Meshanticut Pond and other Rhode Island waterbodies is invasives have already taken root. And the state can’t treat them all — it’s too expensive.

Cost varies based on the size, the weed type, the chemicals used, and the staff time needed. The 12-acre Meshanticut Pond alone cost $6,685 to treat, Dudley said — a price tag picked up by a federal grant program for habitat restoration.

Each year, DEM makes a list of priority treatment sites — based on which are in the worst shape, which are stocked with fish, and which bring in the most complaints, among other variables. But without behavior change and public attention to the causes, Dudley only sees the problem getting worse and a long road ahead as far as invasive treatments go.

“As far as I can see, it’ll be a continuing thing that we’ll have to fight and battle,” she said. “And … it’s not cheap.”

Caitlin Faulds is an ecoRI News journalist.

Grace Kelly: Floating turbines may be part of New England offshore-wind network

Floating turbines come in various styles.

— Joshua Bauer/U.S. Department of Energy

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

The winds and airs currents swirling around the oceans of this blue marble have the potential to power our cities and towns. And locally in coastal New England, the race to harness the power of coastal wind has been accelerating.

Last year then-Rhode Island Gov. Gina Raimondo signed an executive order that called for an ambitious, yet somewhat vague, “100 percent renewable energy future for Rhode Island by 2030” — a good portion of which would be from offshore wind.

“There is no offshore wind industry in America except right here in Rhode Island,” Raimondo said at the time. She was referring to the groundbreaking five-turbine Block Island Wind Farm, a 30-megawatt project that was the first commercial offshore wind facility in the United States.

Today, there is a slightly different picture forming, and other New England states, notably Massachusetts and Maine, are looking into becoming a part of a regional offshore wind network.

During a March 18 online presentation, Environment America discussed a recently released report detailing the overall potential that offshore wind has, specifically in New England. The discussion also included presentations from experts in the field of offshore wind.

“We found that the U.S. has a technical potential to produce more than 7,200 terawatt-hours of electricity in offshore wind,” said Hannah Read of Environment America, a federation of state-based environmental advocacy organizations. “What we did was we compared that to both our electricity used in 2019 and the potential electricity used in 2050, assuming that we transition society to run mostly on electric rather than fossil fuels, and what we found is that offshore wind could power our 2019 electricity almost two times over, and in 2050 could power 9 percent of our electricity needs.”

On a more granular level, Read said Massachusetts has the highest potential for offshore-wind-generation capacity, and Maine has the highest ratio of potential-generation capacity relative to the amount of electricity that it uses.

Massachusetts is entering the final stages of the federal permitting process for the 800-megawatt Vineyard Wind project, which is slated to start construction next year and go online in 2023.

“We have some real frontrunners here in New England and we have a huge opportunity to take advantage of this resource,” Read said. “When you look at the New England as a region, it could generate more than five times its projected 2050 electricity demand.”

While Rhode Island and Massachusetts are looking to more traditional fixed-bottom turbines, in coastal Maine, where coastal waters are deeper, researchers at the University of Maine are testing prototypes for floating wind turbines.

“The state of Maine has deep waters off its coasts. If you go three nautical miles off the coast … you’re in about 300 feet of water,” said Habib Dagher, founding executive director of the Advanced Structures & Composites Center at the University of Maine. “Therefore, you can’t really use fixed-bottom turbines.”

To mitigate this, Dagher and his team have been building and testing floating turbines for the past 13 years, using technology from an unlikely source.

“There are three different categories of floating turbines and ironically enough we have the oil and gas industry to thank for developing floating structures,” Dagher said. “We borrowed these designs … and adapted them to floating turbines.”

Many of these floating turbines rely on mooring lines and drag anchors to keep them from floating away, and they come in various styles.

Dagher noted that while other states are able to pile-drive turbines, they should consider floating turbines as another way to fit more wind power into select offshore areas that could become crammed full.

“We’re going to run out of space to put fixed-bottom turbines. We have to start looking at floating … on the Massachusetts coast and beyond, in the rest of the Northeast,” he said.

Shilo Felton, a field manager for the Audubon Society’s Clean Energy Initiative, addressed another issue facing offshore wind: bird migration patterns. Focusing on the northern gannet, a large seabird, she explained that while climate change itself is negatively affecting bird populations, it is important to take care that offshore wind doesn’t make the situation worse.

She noted that Northern Gannets experience both direct and indirect risks from offshore wind. “Direct risks are things like collision, indirect risks are things like habitat loss,” Felton said.

But Felton also acknowledged that since we don’t really have lots of large-scale wind projects in the United States currently, it’s hard to really say how much those risks will impact bird populations.

“We don’t have any utility-scale projects yet, so we don’t really know how the build out in the United States is going to impact species,” she said. “So that requires us to take this adaptive management approach where we monitor impacts as we build out so that we can understand what those impacts are.”

Overall, the potential that offshore wind holds as a viable mitigation tactic in the fight to curb and eventually eradicate greenhouse-gas emissions is great. But, as speakers noted, implementation has to be done thoughtfully and thoroughly.

Referring specifically to Maine, Dagher said, “The state is moving on to do a smaller project of 10 to 12 turbines, and that would help us crawl before we walk, walk before we run. Start with one, then put in 10 to 12 and learn the ecological impacts, learn how to work with fisheries, learn how to better site these things before we go out and do bigger projects in the future.”

Grace Kelly is an ecoRI News journalist.

Grace Kelly: Waste management important in suppressing coyote population

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

On a recent Friday afternoon, online viewers watched as Numi Mitchell, lead scientist for the Narragansett Bay Coyote Study (NBCS), held what looked like a large antenna in one hand and a beeping device in her other. An osprey cries overhead, and if it weren’t for the Providence Police Department’s Clydesdale horses in the paddock, you wouldn’t know that Mitchell was in Roger Williams Park.

“She’s here!” Mitchell said, as a particularly loud beep sounded.

She being a female coyote named Whinny, who is making her way through the park along with her three pups. Some other hot spots on Whinny’s travels include a trash-collection area in the park and the wind turbines near Save The Bay on Providence’s working waterfront.

The NBCS, which started in 2004, tracks local coyotes, like Whinny, in an effort to observe their movements and populations and to pinpoint unnatural food sources such as trash-disposal areas and farm-animal byproducts.

Coyotes are omnivores, eating a variety of food from berries to bunnies. But they are also opportunistic, and a dumpster can provide an easy meal with little effort.

In her 16 years studying Rhode Island’s coyote populations, Mitchell has found that the increase in the animal’s numbers can largely be attributed to people’s carelessness with food and their compulsion to feed wild animals.

Before coyotes arrived in Rhode Island and other areas along the East Coast, they were dwellers of the broad expanse of prairie in the country’s interior.

“They were originally from the Great Plains,” said Mary Gannon, wildlife outreach coordinator for the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management’s Division Fish and Wildlife. “But when European settlers came [to New England], they cut down forests and killed a lot of the natural predators in our area.”

Some native predators that predated coyotes in Rhode Island and New England included the gray wolf, mountain lions, and bears. With these large predators gone, there was room for coyotes. They moved in.

“The coyotes expanded their territory to the north and south of the U.S.,” Gannon said.

She said they first arrived in Rhode Island in the 1960s and reached the Narragansett Bay islands in the mid-’90s. Soon after their arrival, the state’s coyote populations began to quickly increase, thanks to ample access to human-produced trash.

“Our tracking efforts started on the islands, particularly Aquidneck Island, which was seeing an explosion of coyotes,” Mitchell said. “We were trying to figure out why they were so abundant. And it’s the garbage that is subsidizing the coyote’s diet. It’s not the coyotes that are the problem; it’s people leaving trash outside.”

While hunting of coyotes is allowed, NBCS has maintained that it’s trash management that is the key to reducing coyote populations.

In 2018, NBCS received a $1.1 million federal grant to fund a five-year study of coyotes in Rhode Island, part of which includes food-removal experiments across the state. Mitchell noted that one of these efforts will be with a farmer in the Coventry village of Greene, whose animal waste and byproduct has attracted and fed coyotes in the area.

Back at the Providence police paddock, Mitchell and her crew try to coax Whinny out from her hiding place to offer a fleeting glance to online viewers. They hop the fence, and with a shaking camera and curious Clydesdales running over to get a piece of the action, it feels like a James Bond film.

Suddenly, they gasp at the sound of paws crunching delicately in the underbrush.

“She just ran by us,” whispered Gabrielle De Meillon, a technical staff assistant for DEM. Whinny is a pixelated streak of gray as she continues on her way to seek out trash and continue her journey through Providence.

Grace Kelly is an ecoRI News journalist.

Disease threatens beech trees

North American beech tree in the fall

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

The Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (DEM) is asking residents to monitor beech trees for signs of leaf damage from beech leaf disease (BLD). Early symptoms include dark striping on a tree’s leaves parallel to the leaf veins and are best seen by looking upward into a backlit canopy.

The dark striping is caused by thickening of the leaf. Lighter, chlorotic striping may also occur. Both fully mature and young, emerging leaves show symptoms. Eventually, the affected foliage withers, dries, and yellows. Drastic leaf loss occurs for heavily symptomatic leaves during the growing season and may appear as early as June, while asymptomatic and mildly symptomatic leaves show no or minimal leaf loss. Bud and leaf production also are impacted.

BLD was detected in the Ashaway area of Hopkinton and in coastal Massachusetts this year, according to DEM. Before these findings, the disease was only known to be in Ohio, Pennsylvania, New York, and Connecticut. The disease is caused by a kind of nematode, microscopic worms that are the most numerically abundant animals on the planet.

While there are good species of nematodes, the BLD nematodes cause leaf damage that leads to tree decline and death. At this time, they are known to only affect American, European, and Oriental beech species. Currently, there is no defined treatment, as nematodes are difficult to control in the forest environment. Research is underway to identify possible treatments for landscape trees.

All ages and size of beech are affected, although the rate of decline can vary based on tree size. In larger trees, disease progression is slower, beginning in the lower branches of the tree and moving upward. The disease also appears to spread faster between beech trees that are growing in clone clusters, as it can spread through their connected root systems. Most mortality occurs in saplings within two to five years. Where established, BLD mortality of sapling-sized trees can reach more than 90 percent, according to DEM.

The state agency encourages homeowners and forest landowners to monitor their beech trees and report any suspected cases of BLD to DEM’s Invasive Species Sighting Report.

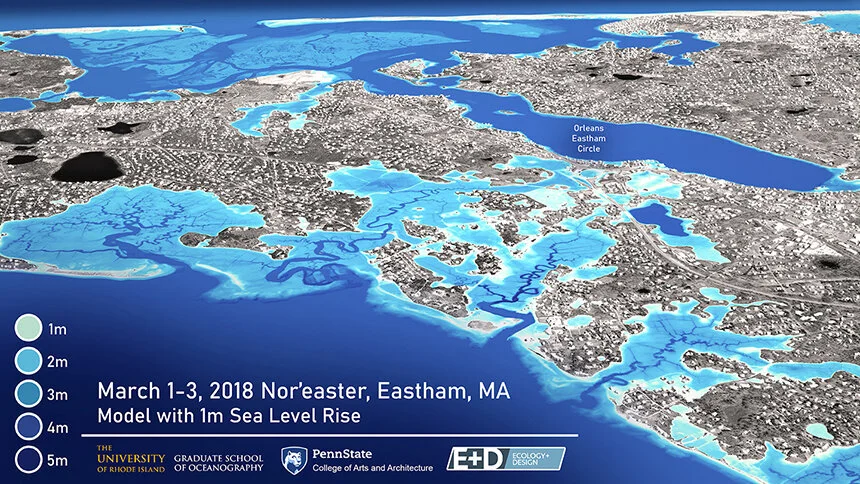

Tim Faulkner: Opposition mounts to seismic blasting off East Coast to find oil and gas

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse, D-R.I., and environmental groups intend to resist the recent announcement of plans to commence seismic blasting for offshore oil and gas drilling. But time may be running out to prevent it.

Seismic blasting uses underwater airguns to search for fossil fuels deep beneath the seafloor, a process that endangers marine mammals such as whales and dolphins.

On Nov. 30, the National Marine Fisheries Service issued what is known as incidental harassment authorizations (IHA) to five companies for conducting seismic testing in an area from Delaware to Florida, a region twice the size of California.

The companies are ION GeoVentures, based in Houston; Spectrum Geo Inc. of England; TGS-NOPEC Geophysical Company of Norway; WesternGeco of England, and CGG, based in Paris.

Whitehouse called their approval “a statement” and “just an idea” that could be stalled by Congress. But according to the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM), the five authorizations are under final review and seismic surveys could begin as early as January.

The IHA allows the the companies to perform deep-penetration seismic surveys that search thousands of meters below the seafloor for oil, natural gas, and minerals. The federal “incidental take authorization” provision allows the activity to kill, harass, hunt, or capture marine mammals. Harassment is defined as “any act of pursuit, torment, or annoyance which has the potential to injure a marine mammal or marine mammal stock in the wild; or has the potential to disturb a marine mammal or marine mammal stock in the wild by causing disruption of behavioral patterns, including, but not limited to, migration, breathing, nursing, breeding, feeding, or sheltering.”

The federal National Marine Fisheries Service, a division of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, says the potential to displace or harm marine life is minimal because of brief and limited exposure to survey noise.

According to the environmental advocacy group Oceana, the surveys deliver seismic blasts every 10 seconds, 24 hours a day over days or even weeks. Survey boats use dozens of airguns simultaneously to produce a constant blast that can travel thousand of miles.

The impact on sea life is significant. Airgun blasts cause temporary and permanent hearing loss, abandonment of habitat, disruption of mating and feeding, beach strandings and even death, according to Oceana. Airgun blasts also kill fish eggs and larvae.

“For whales and dolphins, which rely on their hearing to find food, communicate, and reproduce, being able to hear is a life or death matter,” according to Oceana.

According to a 2013 report, catch rates of Atlantic cod, haddock, rockfish, herring, sand eel and blue whiting declined by 40 percent to 80 percent because of seismic testing.

Seismic airgun testing in the Atlantic Ocean could injure 138,000 whales, according to BOEM. The noise is particularly threatening to the endangered North Atlantic right whale.

BOEM offers a list of protective measures to reduce harm to sea life, such as halting airgun use when animals get too close to vessels.

When a similar proposal was advanced under President Obama, more than 90 percent of the coastal communities in the Mid- and South Atlantic passed resolutions opposing the practice. The dissent was known as the Resolution Revolution, organized by Oceana. Shortly before Turmp took office in 2017, the Obama administration denied the applications for seismic testing in the Mid and South Atlantic, citing impacts on marine life. President Trump and Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke reversed that decision in May 2017, with the America-First Offshore Energy Strategy.

In January, Zinke announced plans to open the entire East and West coasts to offshore fossil-fuel exploration, prompting broad public opposition and efforts by coastal governors to meet with Zinke to convince him to halt the initiative.

In February, Gov. Gina Raimondo and Rhode Island’s congressional delegation held a press conference to announce their opposition to offshore drilling. Block Island, Charlestown, Jamestown and Tiverton all passed resolutions opposing offshore drilling and seismic blasting.

During a 45-day comment period on the proposed seismic airgun testing, the National Marine Fisheries Service received 15 petitions with a total of 99,423 signatures. Only one petition, with 595 signatures, supported the seismic surveys. The 14 other petitions with nearly 99,000 signatures opposed seismic blasting, as well as oil and gas drilling in the Atlantic Ocean.

After the recent news of forthcoming seismic testing, Whitehouse said South Atlantic Republicans “would do well to remember the job Oceana did with the Obama administration trying for offside drilling.”

Whitehouse intends to work with the Commerce Committee and Appropriations Committee “to align our folks” to halt the seismic surveys and offshore oil and gas extraction.

On Dec. 11, Whitehouse, Sen. Edward J. Markey, D-MA, and six other senators asked the Department of Commerce to rescind IHA’s and the Department of Interior to deny the seismic survey permits. In a letter, the senators cite environmental threats and economic harm to tourism and fishing. They also noted that the results of the surveys would be kept private by the survey companies and not available for government or public use.

BOEM, however, is already reviewing the survey applications and could approve them by January.

“If they try to move up to the Northeast, they’ll find that the opposition is bipartisan,“ Whitehouse said. “So, I think we have a real prospect of stopping it, but it’s hard to stop something that’s at this point is just an idea, a statement. Once it hits the administrative steps, we’ll figure out what the best way to counterattack is.”

The counterattack is also going through the courts, primarily in the South. On Dec. 11, Oceana and eight other environmental groups filed in U.S. District Court in South Carolina a lawsuit that claims that by issuing the IHA, the National Marine Fisheries Service ignored science and violated the Marine Mammal Protection Act, the Endangered Species Act, and the National Environmental Policy Act. The lawsuit wants the authorizations suspended until environmental assessments are performed.

If and when the seismic blasting get underway, Oceana will track the activity with a real-time map.

Tim Faulkner is a reporter and writer for ecoRI News.