Llewellyn King: Three out-of-step environmental groups

Rachel Carson researching with Robert Hines on the New England coast in 1952. Her book Silent Spring helped launch the environmental movement.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Greedy men and women are conspiring to wreck the environment just to enrich themselves.

It has been an unshakable left-wing belief for a long time. It has gained new vigor since The Washington Post revealed that Donald Trump has been trawling Big Oil for big money.

At a meeting at Mar-a-Lago, Trump is reported to have promised oil industry executives a free hand to drill willy-nilly across the country and up and down the coasts, and to roll back the Biden administration’s environmental policies. All this for $1 billion in contributions to his presidential campaign, according to The Post article.

Trump may believe that there is a vast constituency of energy company executives yearning to push pollution up the smokestack, to disturb the permafrost and to drain the wetlands, but he has gotten it wrong.

Someone should tell Trump that times have changed and very few American energy executives believe — as he has said he does — that global warming is a hoax.

Trump has set himself not only against a plethora of laws, but also against an ethic, an American ethic: the environmental ethic.

This ethic slowly entered the consciousness of the nation after the seminal publication of Silent Spring, by Rachel Carson, in 1962.

Over time, concern for the environment has become an 11th Commandment. The cornerstone of a vast edifice of environmental law and regulation was the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969. It was promoted and signed by President Richard Nixon, hardly a wild-eyed lefty.

Some 30 years ago, Barry Worthington, the late executive director of the United States Energy Association, told me that the important thing to know about the energy-versus-environment debate was that a new generation of executives in oil companies and electric utilities were environmentalists; that the world had changed and the old arguments were losing their advocates.

“Not only are they very concerned about the environment, but they also have children who are very concerned,” Worthington told me.

Quite so then, more so now. The aberrant weather alone keeps the environment front-and-center.

This doesn’t mean that old-fashioned profit-lust has been replaced in corporate accommodation with the Green New Deal, or that the milk of human kindness is seeping from C-suites. But it does mean that the environment is an important part of corporate thinking and planning today. There is pressure both outside and within companies for that.

The days when oil companies played hardball by lavishing money on climate deniers on Capitol Hill and utilities employed consultants to find data that, they asserted, proved that coal use didn’t affect the environment are over. I was witness to the energy-versus-climate-and-environment struggle going back half a century. Things are absolutely different now.

Trump has promised to slash regulation, but industry doesn’t necessarily favor wholesale repeal of many laws. Often the very shape of the industries that Trump would seek to help has been determined by those regulations. For example, because of the fracking boom, the gas industry could reverse the flow of liquified-natural-gas at terminals, making us a net exporter not importer.

The United States is now, with or without regulation, the world’s largest oil producer. The electricity industry is well along in moving to renewables and making inroads on new storage technologies like advanced batteries. Electric utilities don’t want to be lured back to coal. Carbon capture and storage draws nearer.

Similarly, automakers are gearing up to produce more electric vehicles. They don’t want to exhume past business models. Laws and taxes favoring EVs are now assets to Detroit, building blocks to a new future.

As the climate crisis has evolved so have corporate attitudes. Yet there are those who either don’t or don’t want to believe that there has been a change of heart in energy industries. But there has.

Three organizations stand out as pushing old arguments, shibboleths from when coal was king, and oil was emperor.

These groups are:

The Sunrise Movement, a dedicated organization of young people that believes the old myths about big, bad oil and that American production is evil, drilling should stop, and the industry should be shut down. It fully embraces the Green New Deal — an impractical environmental agenda — and calls for a social utopia.

The 350 Organization is similar to the Sunrise Movement and has made much of what it sees as the environmental failures of the Biden administration — in particular, it feels that the administration has been soft on natural gas.

Finally, there is a throwback to the 1970s and 1980s: an anti-nuclear organization called Beyond Nuclear. It opposes everything to do with nuclear power even in the midst of the environmental crisis, highlighted by Sunrise Movement and the 350 Organization.

Beyond Nuclear is at war with Holtec International for its work in interim waste storage and in bringing the Palisades plant along Lake Michigan back to life. Its arguments are those of another time, hysterical and alarmist. The group doesn’t get that most old-time environmentalists are endorsing nuclear power.

As Barry Worthington told me: “We all wake up under the same sky.”

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island.

Chris Powell: Conn.’s foolish EV promotion program

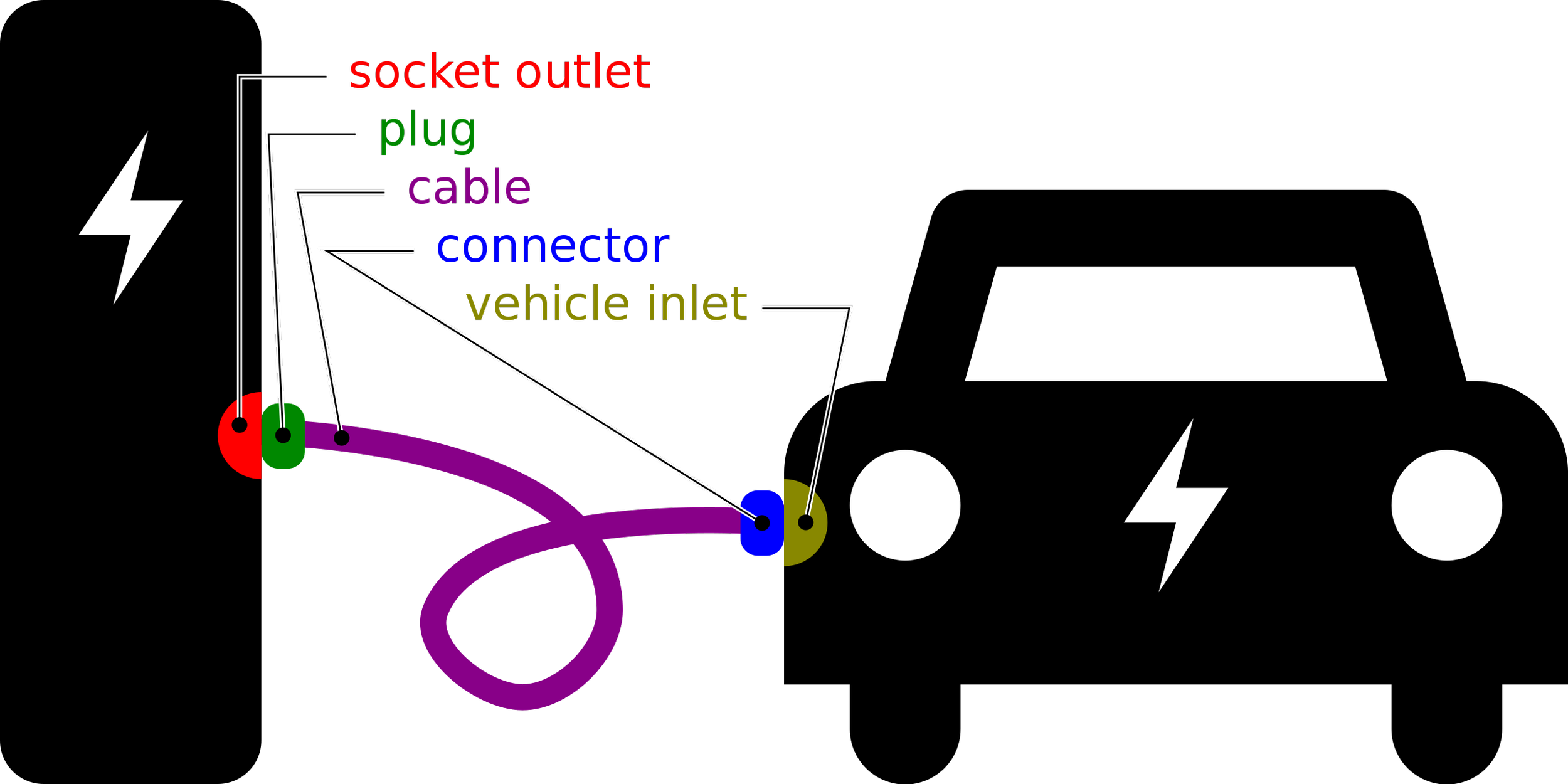

Graphic by Mliu92

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Connecticut Gov. Ned Lamont and leaders of the Democratic majority in the General Assembly are planning to call a special session of the legislature next week to enact the strict California standards for auto emissions that were declined by the General Assembly's Regulations Review Committee in November. Back then two Democratic legislators on the committee from working-class districts seemed to understand that the California standards, outlawing sale of new gasoline-powered cars as of 2035, would leave the working class much poorer than the elites who can afford to toy with electric vehicles.

The governor is said to be giving assurances to legislators, especially those from racial and ethnic minority groups, that the ban on new gas-powered cars could be postponed by new legislation if the performance of electric cars doesn't improve as much as is hoped and if the necessary huge expansion of the state's electricity grid and production doesn't proceed fast enough. The governor and other advocates of the California standards insist that mass conversion to electric cars is inevitable.

But if electric cars are inevitable because they will be so good that everyone will demand them, why must consumer choice be prohibited? Why must Connecticut commit to an expansion of its electricity grid that will cost billions of dollars when there is no plan for it and no idea of how it is to be financed?

The inadequacy of electric vehicles was powerfully demonstrated by the recent frigid weather across the country, with thousands of EVs stranded because batteries don't hold their charges in extreme cold and charging stations are not nearly as common as stations only selling gasoline. And would the people of Connecticut approve outlawing new gasoline-powered cars in another 11 years if they had to decide right now on how to pay the conversion costs? Of course not.

The California standards legislation is mainly a lot of politically correct posturing to lock Connecticut into a future that almost certainly will not turn out exactly as hoped. It is a "buy now, pay later" scheme whose cost is open-ended.

Repealing or postponing the California standards if things don't progress as hoped won't be so easy. By that time, various interest groups will have sprung up to profit from the new policy whether it's working or not and they may be influential enough to block any changes.

Hearst Connecticut newspapers reporter and columnist Dan Haar has noted the special tawdriness of the special session idea. The Democrats, Haar writes, want to enact the California standards before the legislature's regular session begins in February, while the public is not paying close attention and public hearings won't be required.

Before anything is put into law, the governor and other advocates of the California standards should offer a detailed plan and specify its costs and its method of financing, thereby allowing the public to make an informed decision while there is still a choice about paying.

Besides, Connecticut has far more compelling claims on public policy and public finance than whatever its gasoline-powered cars may be contributing to "climate change." Nothing Connecticut or even the whole country can do with auto emissions will come close to offsetting the carbon dioxide and pollutants that inevitably will be put into the atmosphere in coming decades by China, India, and the rest of the developing world.

State government has been prattling about equalizing, integrating, and improving public education at least since the state Supreme Court decision in Horton v. Meskill, in 1977, and 47 years and tens of billions of dollars in extra expense later nothing of substance has changed. Indeed, in recent years Connecticut's per-pupil costs have risen even as school enrollment and student performance have declined.

On top of that, homelessness and crime now are rising in the state amid other signs of social disintegration.

So why should anyone think that state government will succeed with a similarly grandiose project, conversion to electric cars, and that even if it was successful it would make any practical difference anyway?

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years (CPowell@cox.net).

Point us to charging stations

Several Chevrolet Volts at a charging station partially powered with solar panels in Frankfort, Ill.

Text from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Federal and state highway officials need the authority to direct drivers to electric-vehicle-charging stations with signs. This information could be added to roadside signs (before exits) that point to gas stations, food and lodging, or be on separate signs. They’d encourage more people to buy electric cars. Many potential EV buyers shy away from them because of fear that they won’t be able to recharge on longish trips. (Bathroom signs would be nice, too.)

There are already quite a few charging stations in allegedly environmentally conscious southern New England, but they can be hard to find. It sure would be handy if most highway rest stops had them.

Many highway signs include corporate logos of gasoline companies, such as Mobil and Gulf. Signage rule changes would let them include the logos of such electric-charging station operators as Electrify America and EVgo and Tesla (only for its cars). Since not every EV can be charged at every kind of EV charging station, this specificity is important as we try to get people out of their climate-warming, foreign-dictator-boosting gasoline-powered vehicles. We tend to forget that signs are an important part of transportation infrastructure.

But will NIMBY’s block so much potential solar- and wind-power infrastructure that we don’t have enough electricity in the New England grid to charge all these additional vehicles without large continuing use of fossil fuel to generate electricity?

Llewellyn King: Wireless charging on a huge scale a Holy Grail of EV world

The primary coil in the charger induces a current in the secondary coil in the device being charged.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

It is a dream still associated with the Serbian-American inventor Nikola Tesla: broadcasting electricity, making it available to users without a wire.

Tesla took his plans for sending electricity through the air to the grave with him, having been one of the architects of alternating current which was the building block of the electrified world.

But Tesla’s dream has never died and, in fact, is alive and well and making progress -- although not on the universal scale envisioned by Tesla or his followers, who look on his scheme for electricity broadcast from towers, like radio, as a Holy Grail.

His dream was as improbable as it was alluring.

But on a more down-to-earth level, inductive charging – wireless power transfer -- is surging. It has two distinct visions: One is to make wireless charging a reality for small devices. If airport terminals were wired for charging as they are for WiFi, there would be no more sitting on the floor by a plug. The other is for electric vehicles.

Ahmad Glover, the enthusiastic president of WiGL, a small wireless electric transmission company, told me the military is extremely interested in wireless charging. Glover, an Air Force veteran, said the goal is to have forward bases equipped, during operations and in warfighting situations, so that troops can charge their electronics without plugging in. “The less a soldier has to carry the better, “ he said.

Glover, who has worked with engineers from MIT and with Atlantic University, and has a contract with the Air Force, sees a day when charging is essentially automatic. The source of the power could be from a solar charger carried by a soldier in the battlefield rather than from the grid or the forward base generator. Glover believes the work he is doing will keep U.S. troops discreetly in touch wherever, whenever. He is working on beams and omnidirectional area chargers.

The big marquee application for wireless charging is in transportation. Here, most obviously, inductive charging has applications in public transport. The charger consists of an electromagnetic field radiating from a plate to a receiver under the vehicle. When the vehicle is positioned over the plate, charging takes place. This is known as a static system.

Mobile inductive charging, known as dynamic charging, where a moving vehicle can pick up a charge from the roadway, has been promoted overseas. But there is research money in the federal budget for inductive charging development in the United States.

The big advantage of static charging is that vehicles can be lighter and, therefore, cheaper. Taxis, trolleys, light rail, and buses could have smaller, lighter batteries as they will be charged regularly at predictable places, like traffic lights.

South Korea has been developing a charging system for buses where they get a charge every time they stop at a bus stop.

With abundant wind and hydro, Norway is headed for a carbon-free economy. By law, all new cars must be electric by 2025; accordingly, they are working to install inductive charging plates for taxis at their stands. A taxi driver will pull into a stand -- still common in Europe -- and while waiting for the next fare, the car will charge. If the taxi is on the stand long enough, it gets fully charged. Otherwise, it just gets a boost.

The advantages of inductive charging are multiple. First, batteries can be smaller and cheaper, and the vehicle lighter. For utilities, the load is spread over the day, coinciding with the abundance of solar generation.

The ultimate dynamic inductive dream is that cars will refuel as they speed down the highway. Italy has an experimental program installing charging coils in tarmac. Sweden is relatively far along with a similar experiment, and the United Kingdom is funding research.

Nikola Tesla’s dream is turning into reality.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Llewellyn King: Electric revolution to upend transportation

An electric-vehicle charging station, powered by solar panels, in Segovia, Spain

Bright boys and girls are flooding into transportation. It is the place of cutting-edge invention: not cell phones, they were so last year; not computers, they were, er, so last century. The smartest students leaving university may well find the adventure of creating in transportation.

A science-led revolution is in the making in transportation. Leading this revolution is the electric car. It is no longer a drawing-board dream. It is here and gaining market share, albeit miniscule at present.

The surge to electric-powered transportation goes beyond the Tesla and Elon Musk — although Musk has been a catalyst. All manufacturers are now making or investigating electric cars. But the electric car is only a beginning: buses, trucks, trains, small boats, ships and even airplanes are in the mix.

China is throwing government and private resources into an electric future. France, Britain and eight other countries have declared that they will ban the internal- combustion engine by mid-century. Volvo has said that it will stop making fossil- fuel-powered cars.

At the extreme end of the electric-car excitement are automated vehicles. These have caught the imagination — and the dollars — of Google and Uber. But Detroit is also is coming to realize that it has to go electric. General Motors has paved its way with the EV1 and the Volt. Others are scrambling.

The political pressure behind the urge to go electric is clean air, reduced noise and, for many countries, the end of a huge oil bill.

One hundred and forty years after Thomas Edison first perfected a light bulb, electricity is once again a major disruptive technology – and not just on the surface of the Earth. Electric aircraft are in design with short-haul, small-load passenger versions flying in Dubai. Mighty Boeing has teamed up with innovative JetBlue to work on an electric-powered aircraft, although these might have to wait for much better electric-storage batteries than now exist.

Naysayers are quick to point up the inadequacy of batteries — lithium ion are the workhorses in this revolution — and the difficulty of charging them.

These arguments point up a fork in the road for electric enthusiasts: Will the future depend on today’s charging technology where a car has to be tethered to the charging apparatus by a wire, or will electromagnetic fields be used in inductive charging, eliminating the wire? This is known as Wireless Power Transfer (WPT).

Enthusiasts see WPT charging in two ways: either a plate set in a driveway or parking lot with the vehicle at rest or a strip in a roadway which can charge vehicles in motion – a grander idea. If the latter is successful, it opens the way to smaller batteries in lighter vehicles, cheaper trucking.

The disruption is going to be very large.

Gas stations would largely disappear or be very few. Automobile technicians might want to look for alternative employment, as will, eventually, many truck drivers.

The search for new batteries is frenetic and international. New, longer-lived batteries will, in large measure, determine the rate of growth in the more advanced electric vehicle applications.

Another big imponderable is who will provide the electricity? There is a general assumption in the electric utilities that they will do this. But will they? The new owners of the charging networks may choose to make their own with wind, solar and small modular nuclear reactors.

What will the role of government be? Local government will have to deal with the road-use issues. But what of the federal government? It has always been involved in transport. As Peter Morici, the economist and columnist, points out, it stimulated the railways with right-of-way grants and the airlines with mail-hauling contracts. Will it find a similarly elegant way to stimulate the flow of electrons into transportation, and a whole new way of getting ourselves and our stuff around? Maybe it will be led by the military: the Navy wants electric ships.

No wonder the best minds out of colleges and universities are getting wanderlust.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS.