Llewellyn King: Yes. climate change is upon us, but panic isn’t a tool against it

The Kendall Cogeneration Station, in Cambridge, Mass., is a natural-gas- powered station owned by Vicinity Energy that produces both steam and electricity for Boston and Cambridge. We’ll be hooked on natural gas for a long time to come.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

One of the luxuries of democracy is that we don’t have to listen. Or we can listen and hear what we want to hear. We can find resonance in dissonance, or we can hear flat notes.

That is the story of the climate crisis, which is here.

We have been warned over and over, sometimes as gently as a summer zephyr, and sometimes gustily, as with Al Gore’s tireless campaigning and his seminal 1992 book, and later movie, Earth in the Balance.

Now high summer is upon us — with its intimations of worse to come. And this message rings in our ears: The climate is changing — polar ice caps are melting; the sea level is rising; the oceans are heating up; natural patterns are changing, whether it be for sharks or butterflies; and we are going to have to live with a world that we, in some measure, have thrown out of kilter.

Around the beginning of the 20th Century, we began an attack on the environment, the likes of which all of history hadn’t seen, including two centuries of industrial revolution. Sadly, it was when invention began improving the lives of millions of people.

Two big forces were unleashed in the early 20th Century: the harnessing of electricity and the perfection of the internal-combustion engine. These improved life immensely, but there was a downside: They brought with them air pollution and, at the time unknown, started the greenhouse effect.

In the same wave of inventions, we pushed back the ravages of infectious diseases, boosted irrigated farming and enabled huge growth in the world population — all of whom aspired to a better life with electricity and cars.

In 1900, the world population was 1.6 billion. Now it is 8 billion. The population of India alone has increased by about a billion since the British withdrawal, in 1947. Most Indians don’t have cars, jet off for their vacations or have enough, or any, electricity, and very few have air conditioning. Obviously, they are aspirational, as are the 1.4 billion people of Africa, most of whom have nothing. But the population of Africa is set to double in 25 years.

The greenhouse effect has been known and argued about for a long time. Starting in 1970, I became aware of it as I started covering energy intensively. I have sat through climate sessions at places like the Aspen Institute, Harvard and MIT, where it was a topic and where the sources of the numbers were discussed, debated, questioned and analyzed.

Oddly, the environmental movement didn’t take up the cause then. It was engaged in a battle to the death with nuclear power. To prosecute its war on nuclear, it had to advocate something else, and that something else was coal: coal in a form of advanced boilers, but nonetheless coal.

The Arab oil embargo of 1973 added to the move to coal. At that point, there was little else, and coal was held out as our almost inexhaustible energy source: coal to liquid, coal to gas, coal in direct combustion. Very quiet voices on the effects of burning so much coal had no hearing. It was a desperate time needing desperate measures.

Natural gas was assumed to be a depleted resource (fracking wasn’t perfected); wind was a scheme, as today’s turbines, relying heavily on rare earths, hadn’t been created, nor had the solar electric cell. So, the air took a shellacking.

To its credit, the Biden administration has been cognizant of the building crisis. With three acts of Congress, it is trying to tackle the problem — albeit in a somewhat incoherent way.

Some of its plans just aren’t going to work. It is pushing so hard against the least troublesome fossil fuel, natural gas, that it might destabilize the whole electric system. The administration has set a goal that by 2050 — just 27 years from now — power production should produce no greenhouse gases whatsoever, known as net-zero.

To reach this goal, the Environmental Protection Agency is proposing strict new standards. However, these call for the deployment of carbon capture technology which, as Jim Matheson, CEO of the Rural Electric Cooperative Association, told a United States Energy Association press briefing, doesn’t exist.

The crisis needs addressing, but panic isn’t a tool. A mad attack on electric utilities, the demonizing of cars or air carriers, or less environmentally aware countries won’t carry us forward.

Awareness and technology are the tools that will turn the tide of climate change and its threat to everything. It took a century to get here, and it may take that long to get back.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS, and is based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

White House Chronicle

Llewellyn King: 2022’s biggest crises will be 2023’s, too

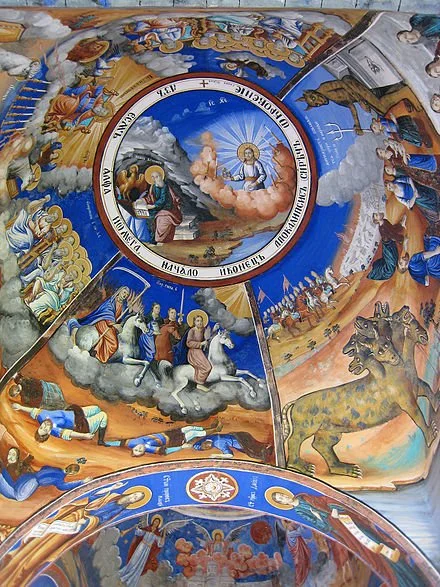

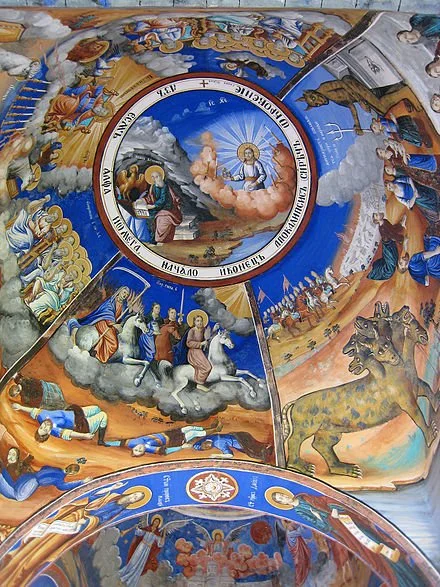

The Apocalypse, depicted in Orthodox Christian traditional fresco scenes in Osogovo Monastery, North Macedonia.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

There are no new years, just new dates.

As the old year flees, I always have the feeling that it is doing so too fast; that I haven’t finished with it, even though the same troubles are in store on the first day of the new year.

Many things are hanging over the world this transition. None is subject to quick fixes.

Here are the three leading, intractable mega-issues:

First, the war in Ukraine. There is no resolution in sight as Ukrainians survive as best they can in the rubble of their country, subject to endless pounding by Russian President Vladimir Putin. It is as ugly and flagrant an aggression as Europe has seen since days of Hitler and Stalin.

Eventually, there will be a political solution or a Russian victory. Ukraine can’t go on for very long, despite its awesome gallantry, without the full engagement of NATO as a combatant. It isn’t possible that it can wear down Russia with the latter’s huge human advantage and Putin’s dodgy friends in Iran and China.

One scenario is that after winter has taken its toll on Ukraine, and the invading forces, a ceasefire-in-place is declared, costing Ukraine territory already held by Russia. This will be hard for Kyiv to accept -- huge losses and nothing won.

Kyiv’s position is that the only acceptable borders are those that were in place before the Russian invasion of Crimea in 2014. That almost certainly would be too high a price for Russia.

Henry Kissinger, writing in the British magazine “The Spectator,” has proposed a ceasefire along the borders that existed before the invasion of last February. Not ideal but perhaps acceptable in Moscow, especially if Putin falls. Otherwise, the war drags on, as does the suffering, and allies begin to distance themselves from Ukraine.

A second huge, continuing crisis is immigration. In the United States, we tend to think that this is unique to us. It isn’t. It is global.

Every country of relative peace and stability is facing surging, uncontrolled immigration. Britain pulled out of the European Union partly because of immigration. Nothing has helped.

This year 504,000 immigrants are reported to have made it to Britain. People crossing the English Channel in small boats, with periodic drownings, has worsened the problem.

All of Europe is awash with people on the move. This year tens of thousands have crossed the Mediterranean from North Africa and landed in Malta, Spain, Greece and Italy. It is changing the politics of Europe: Witness the new right-wing government in Italy.

Other migrant masses are fleeing eastern Europe for western Europe. Ukraine has a migrant population in the millions seeking peace and survival in Poland and other nearby countries.

The Middle East is inundated with refugees from Syria and Yemen. These millions follow a pattern of desperate people wanting shelter and services, but eventually destabilizing their host lands.

Much of Africa is on the move. South Africa has millions of migrants, many from Zimbabwe, where drought has worsened chaotic government, and economic activity has come to a halt because of electricity shortages.

Venezuelans are flooding into neighboring Latin American countries, and many are journeying on to the southern border of the United States.

The enormous movement of people worldwide in this decade will have long-lasting effects on politics and cultures. Conquest by immigration is a fear in many places.

My final mega-issue is energy. Just when we thought the energy crisis that shaped the 1970s and 1980s was firmly behind us, it is back -- and is as meddlesome as ever.

Much of what will happen in Ukraine depends on energy. Will NATO hold together or be seduced by Russian gas? Will Ukrainians survive the frigid winter without gas and often without electricity? Will the United States become a dependable global supplier of oil and gas, or will domestic climate concerns curb oil and gas exports? Will small modular reactors begin to meet their promise? Ditto new storage technologies for electricity and green hydrogen?

Energy will still be a driver of inflation, a driver of geopolitical realignments, and a driver of instability in 2023.

Add to worsening weather and the need to curb carbon emissions, and energy is as volatile, political, and controversial as it has ever been. And that may have started when English King Edward I banned the burning of coal in 1304 to curb air pollution in the cities.

Happy New Year, anyway.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Llewellyn King: The new normal will take time, not politics

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Loud detonations are going off in the economy. When the debris settles, new realities will emerge. We won’t return to the status quo ante, although that is what politicians like to promise.

After great cataclysmic events — wars, natural disasters or the impact of new technologies — we need to acknowledge the realities and find the opportunities.

The inflation that is shaking the world is the inflammation that arises as markets seek equilibrium — as markets always do.

The greatest disrupter has been the COVID-19 pandemic, and the ramifications of how it has reshaped economies and societies are still evolving. For example, will we need as much office space as we did pre-pandemic? Is the delivery revolution the new normal?

Russia’s war in Ukraine has added to the pandemic-caused changes before they have fully played out. They, in turn, were playing out against the larger imperatives of climate change, and the sweeping adjustments that are underway to head off climate disaster.

Some political actions have exacerbated the turbulence of the economic situation, but they aren’t the root causes, just additional economic inflammation. These include former president Donald Trump’s tariffs and President Biden’s mindless moves against pipelines, followed by attempts to lower gasoline prices, or wean us from natural gas while supplying more natural gas to Europe.

In the energy crisis (read shortage) of the 1970s, I invited Norman Macrae, the late, great deputy editor of The Economist, to give a speech at the annual meeting of The Energy Daily, which I had created in 1973 — and which was then a kind of bible to those interested in energy and the crisis. Macrae, who had a profound influence in making The Economist a power in world thinking, shared a simple economic verity with the audience: “Llewellyn has invited me here to discuss the energy crisis. That is simple: the consumption will fall, and the supply will increase. Poof! End of crisis. Now, can we talk about something interesting?”

Of the many, many experts I have brought to podiums around the world, never has one been as warmly received as Macrae. Not only did the audience stand and applaud, but many also climbed on their chairs and applauded. I’m not sure Washington’s venerable Shoreham Hotel had ever seen anything like that, at least not at a business conference.

In today’s chaotic situation with political accusations clashing with supply realities, the temptation is to find a political fix while the markets seek out the new balance. Politicians want to be seen to do something, no matter what, and before it has been established what needs to be done.

An example of this was Biden increasing the allowed amount of ethanol derived from corn and added to gasoline. It is so small an addition that it won’t affect the price at the pump, but it might affect the price of meat at the supermarket. Corn is important in raising cattle and feeding large parts of the world.

There is a global grain crisis as a result of Russia’s war in Ukraine, which is a huge grain producer. Parts of the world, especially Africa, face starvation. The last thing that is needed is to sop up American grain production by burning it as gasoline.

We are, in the United States, gradually moving from fossil fuels to renewables, but this is going to move our dependence offshore, and has the chance of creating new cartels in precious metals and minerals.

Essential to this move is the lithium-ion battery, the heart of electric vehicles and battery storage for renewables, and its tenuous supply chain. Lithium has increased in price nearly 500 percent in one year. It is so in demand that Elon Musk has suggested he might get into the lithium mining business.

But lithium isn’t the only key material coming from often unstable countries: There is cobalt, mostly supplied from the Democratic Republic of the Congo; nickel, mostly sourced in Indonesia; and copper, where supply comes primarily from Chile.

Across the board, supplies will increase, and demand will decline. Equilibrium will arrive, but vulnerability won’t be eliminated. That is an emerging supply chain constant as the economy shifts to the new normal.

The aftershocks of the pandemic and Russia’s war in Ukraine will be felt for a long time — and endured as inflation.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.