Pandemic of plastic pollution

Polystyrene foam beads on a beach.

-- Photo by G.Mannaerts

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Plastic pollution very seriously threatens our ecosystems.

Thus it was good to learn that the University of Rhode Island has won a $1 million contract to research the effects of this growing and still inadequately understood pollution in the water and on land that kills wild animals and harms human health. To get some sense of how serious this problem has become, just walk on a beach.

The reputation of URI’s Graduate School of Oceanography is the major reason the university won this contract.

Hit this link for an article about international plastic pollution of the ocean.

Jim Hightower: Fossil-fuel companies rush to create even more plastic pollution

Via OtherWords.org

In a world that’s clogged and choking with a massive overdose of plastic trash, you’ll be heartened to learn that governments and industries are teaming up to respond forcefully to this planetary crisis.

Unfortunately, their response has been to engage in a global race to make more plastic stuff — and to force poor countries to become dumping grounds for plastic garbage.

Leading this Kafkaesque greedfest are such infamous plunderers and polluters as Exxon Mobil, Chevron, Shell and other petrochemical profiteers. With fossilpfuel profits crashing, the giants are rushing to convert more of their over-supply of oil into plastic.

But where to send the monstrous volumes of waste that will result? The industry’s chief lobbyist outfit, the American Chemistry Council, looked around last year and suddenly shouted: “Eureka, there’s Africa!”

In particular, they’re targeting Kenya to become “a plastics hub” for global trade in waste. However, Kenyans have an influential community of environmental activists who’ve enacted some of the world’s toughest bans on plastic pollution.

To bypass this inconvenient local opposition, the dumpers are resorting to an old corporate power play: “free trade.” Their lobbyists are pushing an autocratic trade agreement that would ban Kenyan officials from passing their own laws or rules that interfere with trade in plastic waste.

Trying to hide their ugliness, the plastic profiteers created a PR front group called “Alliance to End Public Waste.” But — hello — it’s not “public” waste. Exxon and other funders of the alliance make, promote, and profit from the mountains of destructive trash they now demand we clean up.

The real problem is not waste, but plastic itself. From production to disposal, it’s destructive to people and the planet. Rather than subsidizing petrochemical behemoths to make more of the stuff, policymakers should seek out and encourage people who are developing real solutions and alternatives

OtherWords columnist Jim Hightower is a radio commentator, writer and public speaker.

Frank Carini: Plastic pollution is burying a coastline

Rhode Island beach scene

—Photo by Frank Carini

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

Dave McLaughlin has been organizing, leading and documenting Rhode Island shoreline cleanups for the past 15 years, and he’s noticed one item, which comes in all shapes, sizes and colors, becoming increasingly prevalent: plastic.

When the Middletown-based nonprofit he leads, Clean Ocean Access, began cleaning up Aquidneck Island’s coastline in 2006, staff and volunteers found bed frames, tires, refrigerators, glass bottles, aluminum cans and lots of fishing gear.

Today, a deluge of plastic now swamps the shoreline. McLaughlin said the petroleum-based tidal wave began about a decade ago. Besides the typical debris of plastic bags, straws, Capri Sun pouches, Styrofoam cups, candy wrappers and omnipresent cigarette butts — most filters are made of cellulose acetate, a plastic — this evolving pollution now features Jewel pods and the explosion of single-use plastics and multilayered packaging.

Multilayered packaging has several thin sheets of different materials, such as aluminum, paper and plastic, that are laminated together. It’s not made for recycling.

This growing amount of plastic packaging is washing up on shorelines worldwide, including along the Ocean State’s 420 miles of coast — arguably the state’s most important economic engine. In 2015, about 45 percent of plastic waste generated globally was from packaging materials, according to a 2018 white paper. A 2017 report found up to 56 percent of plastic packing manufactured in developing countries consists of multilayered materials.

It’s been estimated that every U.S. household uses nearly 60 pounds of multilayered packaging annually. Most isn’t or can’t be recycled, and much, like other plastic-related trash, ends up in the sea or washed up along the coast.

As of 2019, Clean Ocean Access had held 1,171 cleanups and removed nearly 69 tons of marine debris — about 118 pounds per cleanup — from Aquidneck Island’s shoreline and out of its coastal waters. Of the 14 most common items collected on land, half have been predominantly plastic: straws and stirrers; 6-pack holders; food wrappers; caps and lids; bottles; bags; and toys, according to the organization’s 2006-2019 Clean Report.

Of the 13 most common items pulled from the marine waters of Portsmouth, Middletown and Newport, five are plastic heavy: bleach and cleaning bottles; fishing line; sheets and tarps; strap bands; and buoys and floats.

All of these plastic items, on land and in the water, continue to break down into smaller and smaller toxic pieces that work their way up the food chain.

July Lewis, volunteer manager for Save The Bay, has been involved with shoreline cleanups since 2007. She said the one trend that is inescapable is the growing amount of microplastics and “tiny trash” — what she called pulverized pieces of bottle caps, cups and other plastics — that litter Rhode Island’s coastline.

“We are seeing more and more of it every year,” Lewis said. “It’s become part of the ecosystem.”

Peter Panagiotis, the well-known professional surfer better known as Peter Pan, has been surfing in Rhode Island waters, mostly along the coast of Narragansett, since 1963. He told ecoRI News that plastic now litters the coastline.

“There’s more plastic pollution, especially in the winter there is garbage everywhere,” the Pawtucket resident said. “Plastic pollution is the problem. There’s a lot more plastic garbage.”

Plastic debris makes up a growing amount of the material that is picked up annually during Save The Bay coastal cleanups. In 2019, 2,807 volunteers collected 7.8 tons of trash along 94 miles of shoreline — or about 5.5 pounds per person and 166 pounds per mile.

Of the material collected that year, plastic and foam pieces less than 2.5 centimeters long accounted for 27 percent of all the rubbish collected — 42,841 pieces of tiny trash. Microplastics, pieces less than 5 millimeters long (0.5 centimeters), are harder to see and pick up, but they are a growing presence.

The repulsive 2019 haul included plenty of other plastic: candy and chip wrappers (11,136); bags (6,213); straws and stirrers (4,629); lids (1,942); and utensils (1,050).

For nearly a decade, Geoff Dennis has been a one-man cleanup crew for the Little Compton shoreline. Dennis “got a taste for trash” while walking along Goosewing Beach in 2012.

“It really bothers me. The first time I walked with the dog, I came back with over 100 Mylar balloons,” he told ecoRI News in 2017. “If I can start a conversation with people about it, that’s great. But most people just don’t care.”

Between 2012 and 2020, the longtime quahogger picked up 35,607 pieces of trash along the banks of the Sakonnet River and at Goosewing Beach Preserve and a few other places. The vast majority of it was some form of plastic, from bottles to wads for shotgun shells.

In fact, the amount of plastic he has collected just along Little Compton waters is shocking:

Balloons made from the resin polyethylene terephthalate, a clear, strong and lightweight plastic belonging to the polyester family and commonly referred to as Mylar, a registered trademark owned by Dupont Tejjin Films (2012-20): 8,510. That total doesn’t include the 1,194 latex balloons he collected in 2019 and ’20.

Plastic bottle caps (2017 and 2020): 4,107.

Plastic shotgun shells (2017 and 2020): 1,552.

Plastic wads for shotgun shells (2017 and 2020): 527.

Plastic straws (2016-19): 1,526.

Plastic snack bags (2015-2020): 867.

Plastic bags (2018-2020): 440.

Plastic and foam cups (2018-2020): 386.

Plastic coffee cup lids (2020): 94

K-Cup pods (2019 and 2020): 210.

Plastic nips (2020): 207.

Plastic lighters (2017 and 2020): 188.

Plastic bottles and aluminum cans (2012-2020): 15,324.

In some places along Rhode Island’s marine waters, such as Fields Point in Providence, plastic pollution is now part of the shoreline environment. (Save The Bay)

Lewis noted that in some places, such as Fields Point, at the head of Narragansett Bay in Providence, plastic litter is indistinguishable from the natural world. She said most of this shoreline litter is generated from eating, drinking and smoking.

Save The Bay, too, is finding plenty of plastic flotsam and jetsam bobbing in Rhode Island’s coastal waters. The Providence-based organization is playing a leading role in establishing baseline data on the amount of microplastics within the Narragansett Bay watershed. The goal is to highlight this growing problem and draw attention to regional efforts to eliminate single-use plastics, such as cups, straws and bags.

The three staffers — Michael Jarbeau, Kate McPherson and David Prescott — largely responsible for conducting Save The Bay’s trawls for plastic have been surprised by how much they have found in local waters. When they started, they expected some microplastic trawls would come up empty. They’re still waiting for that to happen.

The crew has done more than 24 surface trawls, and every one has produced plastic bits, from nurdles, the raw building blocks for plastic bottles, bags and straws, to microfibers from polyester fleeces and other synthetic clothing to microbeads, which are used in exfoliating scrubs and in some toothpastes.

All of this overused plastic is changing the composition of Rhode Island’s marine waters. These petroleum byproducts don’t biodegrade. They remain in the environment for centuries. Their long-term impacts on environmental and public health aren’t close to being fully understood. Their impact on the natural world, however, has already been well documented.

Plastic bags float in Narragansett Bay, Block Island Sound and the Ocean State’s other marine waters like jellyfish. Turtles, whales and other sea animals often mistake them for food, causing many to starve or choke to death.

Adult seabirds inadvertently feed tiny trash to their chicks, often causing them to die when their stomachs become filled with fake food. As plastic breaks down into smaller fragments — microplastics may contain toxic chemicals as part of their original plastic material or adsorbed environmental contaminants such as PCBs — fish and shellfish become increasingly vulnerable to the toxins these polluted particles collect.

At least two-thirds of the world’s fish stocks are suffering from plastic ingestion, including local seafood favorites striped bass and quahogs.

On the positive side of the Ocean State’s shoreline trash problem, both McLaughlin and Lewis said they are seeing less dumping of big items, such as tires and appliances.

clean-ups by volunteers seem futile, a new batch will soon appear. Why aren't officers of the companies that make these plastics required to clean it up or pay someone to do so?

Frank Carini is editor of ecoRI News.

Frank Carini: Microplastic pollution imperils corals

A recent study found that northern star coral polyps routinely consumed microplastics, shown above in blue, over brine shrimp eggs, shown in yellow.

— Photo by Rotjan Marine Ecology Lab at Boston University

From ecoRI News

Coral reefs form the most biodiverse habitats in the ocean, and their health is essential to the survival of thousands of other marine species. Unfortunately, these vital underwater ecosystems are beginning to get a taste for plastic.

A Roger Williams University professor, working with a team of researchers, recently published a study that found corals will choose to eat plastic over natural food sources. Unsurprisingly, it’s not good for their health, as it can lead to illness and death from pathogenic microbes attached to microscopic plastics. It also adds to the stress already being applied to coral reefs worldwide, by acidifying and warming oceans, other pollution sources, development, and harmful fishing practices, such as dynamiting and bleaching to capture fish for aquariums.

The project grew from concern about the 6,350 million to 245,000 million metric tons of plastic in the world’s oceans, and the 4.8 million to 12.7 million metric tons of new plastic that enter annually.

Photographs and news reports have documented dead whales and seabirds found with stomachs full of plastic and of sea turtles suffocating from plastic straws clogging their nostrils. At least two-thirds of the world’s fish stocks are suffering from plastic ingestion, according to estimates, as much of the planet’s plastic pollution eventually makes its way into the ocean.

Roger Williams University associate professor of marine biology Koty Sharp recently told ecoRI News that plastic pollution presents a growing problem for both water- and land-based ecosystems.

“It’s a huge problem,” she said. “There’s really nowhere left on the planet that hasn’t been touched by plastics. We’re finding plastics in every organism we study.”

As much as plastic proliferation is a problem, Sharp is even more concerned about the impacts of a changing climate and how humans are using natural resources. She pointed to the manmade damage being done to Australia’s Great Barrier Reef as an example.

“We need to quickly and dramatically decrease our dependency on plastics and fossil fuels,” the microbiologist said. “This isn’t a problem a few people can fix.”

The study that Sharp helped author was published recently in London’s science journal, Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. It is the first of its kind to identify that corals inhabiting the East Coast of the United States are “consuming a staggering amount of microplastics,” which alters their feeding behavior and has the potential to deliver fatal pathogenic bacteria.

In their samples of northern star coral, collected off the coast of Jamestown, R.I., each coral polyp — about the size of a pin head — contained more than 100 particles of microplastics, according to the collaborative research team that included Sharp, Randi Rotjan, a research assistant professor of biology at Boston University, and colleagues from UMass Boston, Boston Children’s Hospital Division of Gastroenterology, Harvard Medical School, and the New England Aquarium.

Northern star coral can be found from Buzzards Bay to the Gulf of Mexico. Since it can be found along the coast of most East Coast urban areas, Sharp said it is a “powerful tool” in helping to understand microplastic pollution.

Although this study is the first to document microplastics in wild corals, previous research had found that this same coral species consumed plastic in a laboratory setting. A 2018 study found plastic pollution can promote microbial colonization by pathogens implicated in outbreaks of disease in the ocean.

The study co-authored by Rotjan and Sharp produced similar lab results. When the researchers conducted experiments of feeding microbeads to the corals in their labs, Sharp said they found that the coral would more often choose the fossil-fuel derivative when given the choice between plastic and food of similar sizes and shapes, such as brine shrimp eggs.

In fact, every single polyp, or mouth, that was given the choice ate almost twice as many microbeads as brine shrimp eggs. After the polyps had filled their stomachs with plastic junk food with no nutritional value, they stopped eating the shrimp eggs altogether.

The study showed that bacteria can “ride in” on the microbeads. In the case of the bacteria they used in the lab — the intestinal bacterium E. coli — the microplastic-delivered bacteria killed the polyps that ingested them and their neighboring polyps within weeks, even though the polyps spit the microbeads out after about 48 hours. The E. coli bacterium persisted inside their digestive cavity.

“Research has shown that there are virtually no marine habitats that are untouched by plastics,” said Sharp, noting that research abounds demonstrating that nearly all ocean water contains plastic pollution. “Because of that, it’s critical that we understand the impact of plastics pollution. Microplastics pollution is a matter of global health — ecosystem health and human health.”

She noted that the problem of plastic pollution extends far beyond what can be seen. Plastics never fully degrade in seawater, breaking down into smaller and smaller pieces. Invisible to the naked eye, microplastics remain suspended in the water column, and this is what corals and other filter-feeding animals take in to get their food, she said.

The researchers had anticipated they would find microplastics in wild corals, but they were shocked by the volume present in their samples, according to Sharp.

Another invisible factor is the presence of microbes that hitch rides with plastics floating in the ocean, winding up in the stomachs of many creatures. These plastic-riding microbes are growing in number and upending the delicate balance of ecosystems.

Sharp said the problem is being made worse by human-induced climate change, which is helping bacteria to proliferate. She noted that microplastics in the ocean are coated with microbes.

“We know that plastic particles provide an enriching habitat for bacteria that are not usually in very high numbers in seawater,” Sharp said. “The microbial aspect of microplastics pollution is largely underexplored — it’s critical that we learn more about how plastics can affect the dynamics, abundance, and transport of microbes through our ecosystems and food webs. Alteration of microbiomes in our marine ecosystems by human-induced threats like plastics pollution and climate change holds great potential to impact marine environments on a global scale.”

To help mitigate the problem of plastic pollution, Sharp offered some tips:

Minimize single-use plastics. Use reusable bags and mugs. Buy groceries in bulk. Decline a straw if you don’t need one.

Take a day to count. How many times in one day do you use single-use plastics. What is unnecessary and what can be eliminated or replaced with more sustainable products?

Demand lower-impact packaging and support products with sustainable packaging.

Support and advocate for legislation and lawmakers that promote innovative solutions and alternatives for sustainable packaging.

“Given that plastics pollution is an ongoing threat co-occurring with climate change, it’s critical that we do more research to understand how they impact marine ecosystems together,” Sharp said, “and take immediate actions to minimize human impacts on the world’s oceans.”

Frank Carini is editor of ecoRI News.

Tim Faulkner: Localities stepping in to address ocean plastic crisis

Plastic pollution, especially in the ocean and along the coast, such as these plastic jugs found on the Portsmouth, R.I., shoreline, is a significant global problem.

Photo by Frank Carini of ecoRI News.

Via ecoRI News (ecori.org)

U.S. Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse’s Save Our Seas Act has big goals for addressing plastic in the oceans. The bipartisan bill that passed out of the Senate last year seeks to tackle marine debris and the ballooning problem of plastic waste by authorizing $10 million annually for cleanups of severe debris events in waters across the country. It also restarts federal research to determine the source of marine trash and the steps needed to prevent it.

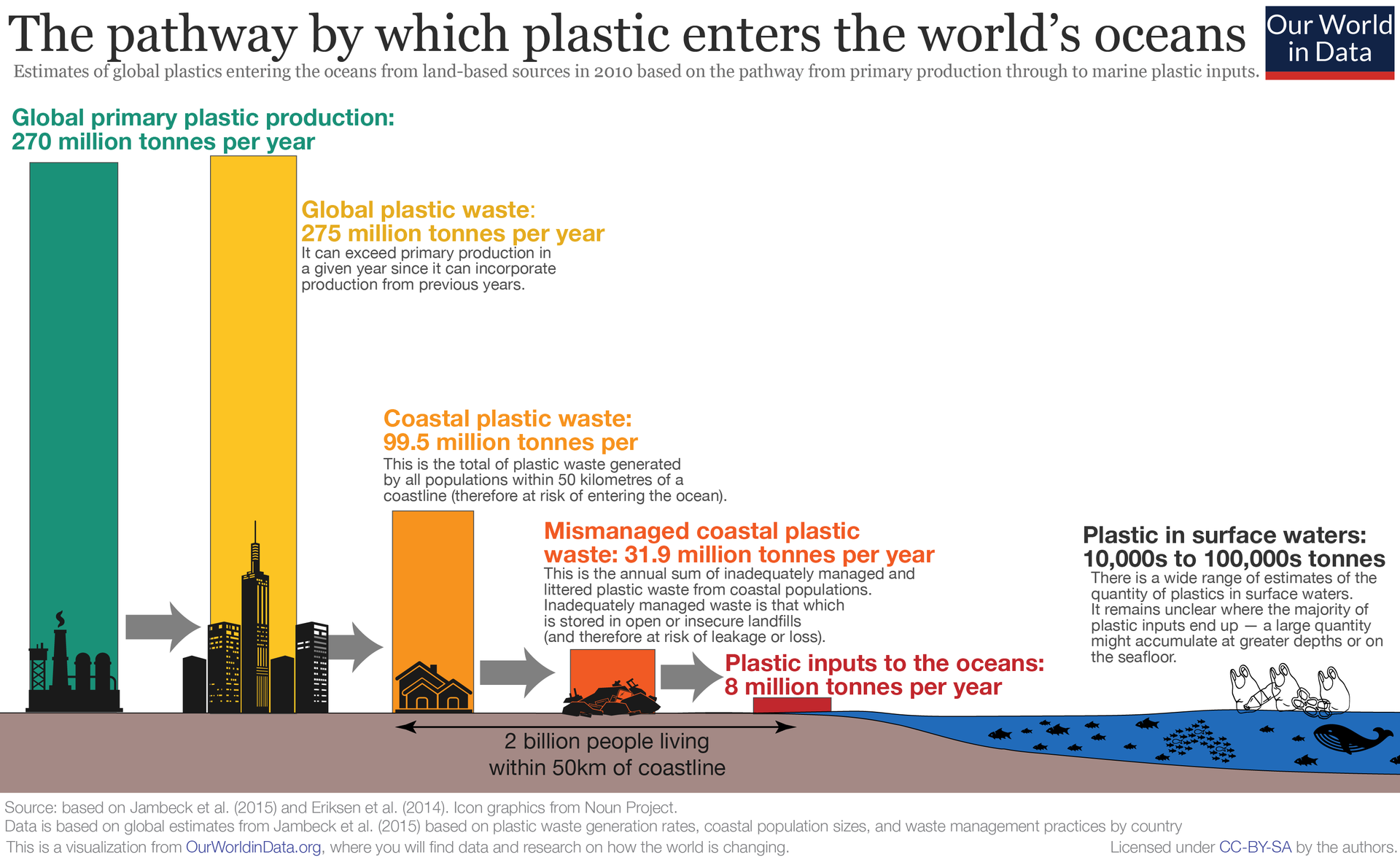

What is already known is that much of the 8 million tons of plastic waste dumped in the world’s oceans each year happens outside the United States. In fact, five countries — China, Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam — are responsible for 60 percent of the plastic garbage that makes it into our waters every year, according to the Ocean Conservancy.

That’s a problem, because most of those five countries receive plastic from U.S. recycling centers. The recycling industry, however, is lightly regulated, so it's hard to know the fate of the millions of bales of plastic recyclables shipped overseas annually.

The Save Our Seas Act addresses this problem by encouraging the president and the State Department to address the marine debris problem with these high-polluting nations. It also encourages international research into biodegradable plastics and establishes prevention strategies.

However, the likelihood of an environmental bill passing in the current Congress, much less President Trump endorsing it, is low. Trump wants to cut $1 billion from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), which overseas the marine-debris program.

For now, much of the action on marine garbage is happening at state and local levels. Those steps include greater enforcement of recycling rules, bans on certain plastics, and improvement by product manufactures to make their packaging more environmentally friendly, reusable and include take-back programs for hard-to-recycle and bulky items.

At a recent Earth Day event in Middletown, R.I., aimed at drawing attention to the Save Our Seas Act, Johnathan Berard of the Rhode Island chapter of Clean Water Action said, “We cannot recycle our way out of this problem. We will only be able to solve it through policies that stop plastic pollution at its source.”

Recycling is necessary but is vulnerable to economic and market pressures, which cause revenues for waste prevention and education to fluctuate. There is little enforcement of rules, such as requirements in Rhode Island, Massachusetts and Connecticut that all business collect recyclables and offer collection for their customers. There is even less oversight of what happens to recyclables once they leave sorting centers and are shipped around the world. And with the exception of metals and glass, plastics eventually lose their durability and are down-cycled to trash.

Depending on the item, recycling rates hover between 20 percent and 30 percent nationally. Requiring a deposit on glass and plastic bottles, so-called “bottle bills,” boost the recycling rate to nearly 90 percent. But the political will for bottle bills is poor. For example, legislation is introduced in the Rhode Island General Assembly each year but rarely makes it out of committee.

The 2018 bill has yet to be scheduled a hearing. Massachusetts has had a successful 5-cent bottle-deposit program since 1983, but voters defeated a referendum in 2014 to expand the collection to include non-carbonate beverage bottles.

Take-back programs for bulky and hard-to-recycle items such as mattresses, paint cans and electronic waste have also made a difference, but expanding programs to other items like light bulbs, syringes and medications have stalled, as manufactures and retailers resist raising prices to fund collection or improvement of packaging.

This resistance puts the cost of waste management and recycling on consumers and local governments who pay for clean up and transportation. Budget limitations have led to the most cost-effective solution: bans. Prohibitions and fees on plastic bags, in particular, have proven effective at reducing land and marine debris. Dozens of communities in Massachusetts have banned plastic bags and a handful have enacted bans on polystyrene cups and to-go containers.

Seven Rhode Island communities have passed bag bans and more are considering them. Block Island even added a ban on balloons, and the “skip the straw” movement is growing among consumers and restaurants.

While bag bans and beach cleanups are helping clean southern New England, there is still the problem of global waste. Global plastic production is expected to double within 10 years and by 2050 there will be more plastic waste by weight in ocean waters than fish.

The Ocean Conservancy says a combination of education, waste collection and recycling infrastructure, and better managed and properly cited landfills are needed to tackle the plastic ocean debris epidemic.

“While we have made enormous progress cleaning up Narragansett Bay, the millions of tons of trash that are dumped into the oceans around the world can wind up on American shores and in the nets of Rhode Island fishermen,” Whitehouse said.

Tim Faulkner reports and writes for ecoRI News.

Frank Carini: Pushing against southern New England's rising tide of toxic plastic

-- Photo by Frank Carini

Via ecoRI.org

There’s an estimated 5.25 trillion pieces of plastic debris in the world’s oceans. Some 8 million tons of plastic enter the sea annually. How much is floating in local marine waters remains a mystery. An answer may be forthcoming, though, as researchers will spend five days next week scouring Narragansett Bay for plastic.

The July 18-22 trash trawl is being conducted by the Rhode Island chapter of Clean Water Action (CWA) to raise public awareness about the most invasive “species” in the ocean: plastic.

Johnathan Berard, state director of CWA Rhode Island, was the policy director at Blue Water Baltimore when the organization partnered with Trash Free Maryland a few years ago to conduct a similar trawl of Chesapeake Bay. While the amount of visible plastic collected was “striking,” the four-day effort also captured a “great deal” of micoplastics — likely photodegraded pieces of plastic bags and wrappers — fishing line, and cellophane rip-strips from cigarette packs.

The Chesapeake Bay trawl and a similar one done on the Hudson River were for scientific research. The Narragansett Bay trawl is more of an advocacy project.

“We want to get elected officials, the press and advocates face to face with the problem,” Berard said. “A jar of Narragansett Bay water filled with plastic is a powerful image.”

Next week’s five-day sweep will employ an ultra-fine mesh net designed to capture micorplastics, microbeads and micofibers. These tiny plastic particles represent the planet’s next big environmental and public-health concern.

Microfibers from polyester fleeces and other synthetic clothing are an emerging concern when it comes to the quality of drinking water. Neither washers nor wastewater treatment facilities are designed to remove these accumulating bits of plastic.

“We can’t keep pushing plastic into the economy,” Berard said. “It wreaks havoc once it’s out in the environment. We find this stuff in our water. It’s in the fish we eat. On our beaches. It’s going to get to a point when it will be too gross to go to the beach or eat fish.”

Plastic packaging isn’t well recycled, or reused. (As You Sow)

Throwaway Economy

The United States alone tosses out 25 billion Styrofoam cups annually, more than 300 million straws daily, and some 3 million plastic bottles every hour of every day. Few of these items are recycled or reused.

“The current system pumps tons of plastic into the economy and environment,” said Jamie Rhodes, program director for UPSTREAM. “The scope of the problem is huge. We can’t burn or recycle our way out of this problem.”

Southern New England is certainly home to its share of plastic pollution. But how much? No one ecoRI News spoke with for this story has any idea, and while they all would be interested in finding out, their bigger concern is how to lessen the local impact of a global problem.

But, as Rhodes, former chairman of the Environmental Council of Rhode Island, noted, we can’t simply ban plastic. “Plastic has raised people out of poverty. I, for one, don’t want a computer made of iron,” he said. “But it’s overused. We need to use it more wisely.”

What is considered a “wise use,” however, can be subjective. One person might think wrapping a cucumber or apple in plastic is a ridiculous waste of resources and feeds the growing waste stream. Another person might argue that such a use of plastic prolongs shelf life and reduces organic waste.

What can’t be debated is the amount of plastic litter collected at beach cleanups in Connecticut, Massachusetts and Rhode Island, roadside debris seen through moving windows, and the flotsam and jetsam that bob in the region’s waters.

“Plastics suck in chemicals. That’s what they’re good at,” Rhodes said. “What’s the long-term impact on humans, on the environment?”

Dave McLaughlin, executive director of Middletown, R.I.-based Clean Ocean Access, noted that “we don’t know the implications of the bioaccumulation of plastics in humans.”

“They’re endocrine disruptors and that is some scary stuff,” he said. “It’s important that we understand the severity of the issue.”

Plastic bags float in Buzzards Bay, Long Island Sound and Narragansett Bay like jellyfish. Turtles, whales and other marine animals often mistake them for food, causing many to starve or choke to death. In fact, all of southern New England’s fresh and salt waters, from hidden brooks to popular beaches, are touched by plastic — a toxic problem that threatens wildlife and public health.

Adult seabirds inadvertently feed small pieces of plastic to their chicks, often causing them to die when their stomachs become filled with petroleum byproducts. As plastic breaks down into smaller fragments — microplastics that may contain toxic chemicals as part of their original plastic material or adsorbed environmental contaminants such as PCBs — fish and shellfish become increasingly vulnerable to the toxins these polluted particles collect.

At least two-thirds of the world’s fish stocks are suffering from plastic ingestion, according to estimates, as much of the planet’s plastic pollution eventually makes its way into the ocean. Local seafood favorites such as stripers and quahogs, for example, are vital to southern New England’s marine food web and the region’s economy.

The countless plastic bags, plastic bottles and plastic wrap strewn along southern New England’s coastline, swimming in the region’s rivers, ponds and lakes, waving from trees, and loitering in parks were each likely used only once, and for just a few minutes. These petroleum byproducts, however, don’t biodegrade. They remain in the environment for centuries. Their long-term impact on environmental and public health is not yet fully understood, and barely studied.

“We’ve plasticized the entire biosphere, including our bodies,” Marcus Eriksen, research director and co-founder of the 5 Gyres Institute, said during a March panel discussion at Brown University titled “The Plastic Ocean.” “The impact of plastic is widespread.”

The world’s plastic problem was first acknowledged in the 1970s. A 1973 survey of the plastic materials accumulating on a private beach on Conanicut Island in Narragansett Bay, for instance, found that the plastic pollutants “were mainly a by-product of recreational activities within the bay and not household, industrial or agricultural refuse.”

The study also noted that “plastic objects manufactured from polyethylene made up the bulk of the flotsam on the beach.” Among the plastic items collected were milk-shake tops, beer-can carriers, fish-hook bags, straws, bleach containers and shotgun pellet holders.

In 1987, the United States eventually responded to the growing plastic problem, with the passage of the Marine Plastic Pollution Research and Control Act. The law, which went to effect Dec. 31, 1988, made it illegal for any U.S. vessel or land-based operation to dispose of plastics in the ocean.

However, this act and other laws like it, such as the Microbead-Free Waters Act of 2015, can’t compete with mass consumption in a throwaway society. Their effectiveness is further limited by Washington, D.C.’s relentless assault on environmental protections, and by non-existent or lax waste-management practices in much of Southeast Asia and in developing countries.

Some four decades since the problems associated with plastic manufacturing and use were first identified, apathy, ignorance, convenience and profit have led to an addiction that is trashing the planet and putting human health at risk.

While our plastic reliance, especially for single-use items, grows, the reuse and recycling of this material has essentially flatlined. Waste-management practices can’t keep pace with the volume of production and the relentless tidal wave of new plastic packaging.

Currently, less than 15 percent of plastics packaging is recycled worldwide, according to As You Sow, a nonprofit foundation chartered to promote corporate social responsibility.

As You Sow is one of about 800 organizations worldwide, including UPSTREAM and the Story of Stuff, united in the goal of dramatically reducing the production of single-use plastic packaging, containers and bags. It’s known as the Break Free From Plastic movement.

Since most plastic is made from fossil fuels, the issue of plastic manufacturing, use and waste is also one of climate change.

“It’s fuel early on, a kid’s juice pouch in the middle, and a fuel at the end,” UPSTREAM’s Rhodes said.

Litter, especially of the plastic variety, costs taxpayers plenty. (Frank Carini/ecoRI News)

Local Impact

Plastic pollution doesn’t just ruin beach getaways and picnics in the park. It also harms the limited exposure many urban children have to nature, according to Leah Bamberger, Providence’s sustainability director.

Last year, the city had a study done to better understand how Providence residents, most notably children, perceive nature and how they use the city’s parks and open spaces. The study found that among the main concerns of children and their parents was the cleanliness of outdoor spaces, particularly litter in parks.

“Litter was the number one barrier that kept kids from enjoying nature and our parks,” Bamberger said. “It debunked the myth that urban kids don’t care about nature.”

Dealing with the region’s litter problem, much of which is some form of plastic, requires taxpayer funding and the ample use of unpaid time.

Staff and volunteers of Clean Ocean Access (COA) have spent the past 11 years cleaning up the Aquidneck Island shoreline. In that time, volunteers have worked nearly 14,000 hours and picked up some 95,000 pounds of debris, much of it plastic, according to McLaughlin, the nonprofit’s executive director.

“There’s litter that’s preventable — the stuff that blows out the back of pickup trucks — and then there’s illegal dumping that’s intentional,” he said. “Most of the plastic we find is from the society of convenience, like packaging and single-use items. A small piece of plastic has a pretty big impact.”

Of the 94,487 pounds of debris collected during 457 cleanups held between 2006 and 2016, much of it was plastic-based, such as bottles, food wrappers, fishing line, straws and cigarette filters, according to the 10-year anniversary report released by COA earlier this year.

All those cigarette butts nonchalantly flicked from car windows and haphazardly dropped on the ground, along with tobacco packaging and plastic lighters, represent one of the main sources of marine debris worldwide. Cigarette butts are made from a plastic called cellulose acetate. It doesn't biodegrade, and can persist in the environment for a long time. This plastic also contains toxins that can leech into water and soil, harming plants and wildlife.

On World Oceans Day, June 8, COA held a coastal cleanup at Easton’s Beach in Newport. Seventy-two volunteers collected 160 pounds of debris, including 1,700 cigarette butts.

Unsurprisingly, plastic bags also make up a good chunk of the organization’s shoreline hauls. Between 2013 and 2016, for example, volunteers picked up 11,874 bags.

The Aquidneck Island coastline, however, isn’t the sole domain for litter. The waters off Newport, Middletown and Portsmouth are also teaming with debris, most notably Newport Harbor. The Rozalia Project has documented a concentration of trash in the historic harbor at 41 million pieces of litter per square kilometer. Trash covers 25.2 percent of the harbor’s seafloor. It’s been dubbed Beer Can Reef, although much of the debris is plastic bottles and cups.

The Long Island Sound Study notes that marine debris is a nuisance and hazard for boaters. For instance, floating lines can foul a boat’s propellers, and chunks of plastic or plastic bags can block an engine’s cooling-water intake.

“While floatable debris in the open waters of Long Island Sound is less concentrated than in the neighboring New York-New Jersey Harbor estuary and in western Long Island Sound embayments, it is present in great enough quantities to mar the aesthetic enjoyment of the Sound,” according to the program that was started in 1985 by the Environmental Protection Agency and the states of New York and Connecticut to improve and protect the water quality of Long Island Sound. “Debris floating in the waters of the Sound can accumulate along with detached seaweed and marsh grass into large surface ‘slicks.’ These slicks can wash ashore fouling beaches and the coastline.”

Plastic caught in fences, lying on beaches, blowing around open spaces and carried by stormwater runoff into the region’s sensitive estuaries is much more than an eyesore. It’s pollution, and it has economic, ecological and public-health impacts. It’s a macro-, micro- and nano-scale problem.

To get a rough idea of the amount of litter accumulating in Rhode Island, McLaughlin did some conservative guesstimating. He figured if 5 percent of the state’s 1 million residents littered once a month, accidental or not, Rhode Island would see 600,000 new pieces of wind-blown trash annually. If 5 percent of the Ocean State’s 3.5 million annual visitors did the same, another 2.1 million pieces would be added to the landscape.

Collectively, southern New England taxpayers spend millions of dollars annually to clean up and prevent litter, much of which is of the plastic variety. Providence and other cities have to spend time and money notifying businesses to keep their Dumpsters closed, so trash doesn’t blow away or get spread about town by animals. DPWs have to clean vacant lots of trash and clear clogged storm drains and catch basins.

It also costs taxpayers when loads of municipal recycling are contaminated — plastic bags are one of the biggest contaminators; biodegradable and compostable plastics are also problem contaminants — and the collected material must then be buried or burned, instead of sold to recyclers.

Despite her relentless efforts organizing cleanups, Massachusetts resident Bonne Combs says, ‘We can’t clean our way out of this problem.’ (Courtesy photo)

No one pays Bonnie Combs to pick up after others. The Blackstone, Mass., resident is a relentless reuser and recycler. She conducts daily one-woman cleanups, at Stump Pond in Smithfield, R.I., up and down the banks of the Blackstone River and in her neighborhood, to name just a few spots. She founded Bird Brain Designs by Bonnie to repurpose animal feed bags into reusable shopping bags.

The marketing director for the Blackstone Heritage Corridor (BHC) manages the organization’s Trash Responsibly program. She also started the BHC’s Fish Responsiblyprogram, which works with businesses, such as Ocean State Tackle in Providence and Barry’s Bait & Tackle in Worcester, and the Audubon Society to make sure monofilament fishing line and spools are recycled properly.

Combs regularly sees firsthand the pervasiveness of southern New England’s plastic problem. She said nips are a “huge problem.” She picks up plenty of iced-coffee cups wrapped in both Styrofoam and plastic, and sees discarded plastic packaging everywhere.

“It’s becoming harder and harder to buy everyday products in recyclable packaging. It’s really frightening,” Combs said. “We have a waste problem. We need to go on a waste diet.”

Since this month is Plastic Free July, perhaps southern New England should start dieting now. But dieting is hard. Much of the world’s food and drink, from coffee to baby food, is now wrapped and shipped in plastic.

Addressing the region’s plastic problem, however, is complicated and will require more than avoiding plastic utensils, plastic bags, plastic water bottles, plastic straws and mylar balloons for a month. McLaughlin, of Clean Ocean Access, said the issue demands a three-pronged approach: policy, which he called “the stick;” technology/innovation, “business taking the lead;” and engagement, “the carrot.”

McLaughlin believes, at this moment at least, all three legs are a little too short.

“It starts with people becoming educated, connected and stewards of the environment,” he said. “We just can’t ban our way to a healthy ocean.”

Policy Improvements

Since the late 1960s, plastic shopping bags have been clogging storm drains, degrading marine ecosystems, choking animals, littering beaches and leaching estrogenic chemicals, but the Ocean State and its two southern New England neighbors lack the political will to enact statewide bans. The American Chemistry Council, the American Petroleum Institute and other lobbyists hold more sway than in-your-face environmental degradation and public-health concerns.

The environmental/public-health impacts associated with plastic manufacturing and disposal include greenhouse-gas emissions, and water and land pollution. For instance, a billion discarded plastic bags is the equivalent of 12 million barrels of oil. These costs are largely ignored.

Lobbyists from D.C. and parts unknown descend whenever a statewide ban or local one is discussed in Connecticut, Massachusetts or Rhode Island. They argue that consumers benefit from the use of plastic bags, because they can easily carry goods without the burden of lugging around reusable bags. They note that plastic bags handed out by retailers are reused as pet-waste containers or to line household trash receptacles. They say properly collected and recycled plastic bags — they shouldn’t be placed in curbside recycling bins and instead be brought back to stores for collection — are made into a composite product used as a wood substitute for decks and stairs.

Unfortunately, only a small percentage of plastic bags are actually recycled. In Rhode Island alone, some 190 million plastic bags are consumed annually, according to a 2006 Brown University study, and only about 9 percent are recycled.

Lobbyists, however, have failed to sway some local municipalities. Three Rhode Island communities — Barrington, Middletown and Newport — have passed bans on plastic retail bags. About 35 municipalities in Massachusetts have similar bans. The first municipality in New England to ban plastic checkout bags was Westport, Conn., in 2008.

While lawmakers in southern New England’s three states have been slow to adequately address the region’s role in the world’s plastic problem, a few western states have attempted to change the paradigm. California enacted a statewide plastic-bag ban last year, despite intense lobbying by plastics manufacturers. A 2013 study of San Jose’s bag ban helped pave the way for California’s statewide ban. The study found that after San Jose enacted its bag ban, there was nearly 90 percent less plastic debris in the city’s storm drains and about 60 percent less plastic street litter.

In Hawaii, all four of the state’s county councils and the city of Honolulu have passed some type of bag ordinance that has effectively banned plastic retail bags in the 50th state.SThis year, Connecticut debated a proposal to put a 5-cent tax on single-use plastic and paper shopping bags. The city of Providence has warned and then fined residents who continue to use their recycling bins for trash. On June 22, for example, the city’s five enforcement officers wrote 50 tickets.

McLaughlin, of Clean Ocean Access, noted that states and municipalities need to support, fund and enforce waste-diversion efforts. In Rhode Island, at least at the state level, resources for such efforts are scarce. In the three decades since the state’s recycling law was enacted, the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management has neither warned nor fined any business for noncompliance.

Bag bans, bag taxes, fines and enforcement, while all part of the solution puzzle, aren’t the key pieces. Producer responsibility, also known as product stewardship, enlists manufactures in the disposal and recycling of the hazardous and bulky goods they produce. In southern New England, producer-responsibility programs already exist for mercury thermometers and thermostats, paint, and mattresses.

Bamberger, Providence’s sustainability director, Rhodes, of UPSTREAM, and CWA’s Berard all told ecoRI News that producer responsibility is vital to local, national and global efforts to reduce plastic pollution, minimize packaging and change practices.

“Bans are nice, but they’re not a good solution,” Bamberger said. “Producer responsibility is the most effective way to manage the waste stream.”

Berard said, “Manufacturers can’t just put all this material into the economy and then have no skin in the game post-use.”

One of UPSTREAM’S focus points is helping make producers more responsible, here and across the globe.

“Companies need to be part of the solution,” Rhodes said. “We need policies to stop the flow of single-use plastic. This isn’t the system we’ve always had. We created it; we can change it.”

Innovation and Technology

They look like small, floating Dumpsters. In their first year of use, the two trash skimmers attached to docks at Perrotti Park removed more than 6,000 pounds of debris from Newport Harbor. Much of the litter was of the usual-suspect variety — plastic food wrappers, straws and bags, and fishing line.

COA’s Newport Harbor Trash Skimmer Projectwas implemented last August, and made possible by funding from 11th Hour Racing. Some 30 units, manufactured by Washington-based Marina Trash Skimmers, are in use on the West Coast and Hawaii. The two installed in Newport Harbor are believed to be the first ones in use on the East Coast.

They operate essentially as large pool skimmers, filtering water 24 hours a day and capturing floating debris and absorbing surface oil or other contaminants. The skimmers are powered by a three-fourths-horsepower electric engine that costs $2 a day to run. Hundreds of gallons of water flow through the units every few hours, and the skimmers are minimally invasive to marine life.

COA has since added a trash skimmer at Fort Adams State Park and at New England Boatworks, in Portsmouth.

“These units are highly effective in removing floating marine debris,” COA’s McLaughlin said. “But we can’t put trash skimmers everywhere.”

A similar piece of equipment in use in Baltimore’s Inner Harbor also removes debris, including plastic litter, from the water. The water-powered wheel deposits the scooped-out trash into a Dumpster. When there isn’t enough water current, a solar panel attached to the unit provides additional power.

New technology, whether it’s floating Dumpsters or trashy water wheels, play a role in controlling litter. To better address plastic manufacturing and use, however, advanced packaging innovations will have to play a bigger role.

Public Engagement

Solving the problem of plastic pollution can’t be done by stopping littering and improving recycling rates. Producer responsibility alone won’t end the deluge. The effort must include education and outreach, to curb such issues as “wishful recycling.” It’s also about changing behaviors — something as simple as restaurants asking if you want a straw rather than just giving you one.

According to a study recently done by UPSTREAM for the city of Providence, one way to address the issue at an individual consumer level is to incentivize behavior to reduce single-use items, such as being allowed to cut the line at the coffee shop if you bring your own mug.

Much of the outreach is needed to make people aware that the region’s plastic problem isn’t magically fixed curbside, or at a transfer station, landfill or incinerator.

“We see litter on the streets and plastics in the ocean, but when we put our recycling out at the curb, we don’t care or know what happens next,” Rhodes said. “Much of the this material is shipped to small, developing countries like the Philippines and Malaysia, where poor waste pickers go through it.”

McLaughlin said the overuse of plastic is a solvable problem. He said it starts with individuals taking action.

“We have to take care of each other and the environment. That’s how we are going to make progress,” McLaughlinsaid. “We have to get people involved at the local level to take action."

Frank Carini is editor of ecoRI News.

Frank Carini: The horrific effects of plastic pollution

The remains of this Laysan albatross chick on Midway Island in the Pacific show the plastic it ingested before death, including a bottle cap and lighter.

The amount of plastic choking the planet, most notably the world’s oceans, is unfathomable. The evidence of this unrelenting assault overwhelming. The scale of this toxic pollution horrifying.

Consider:

It’s estimated that there are 5.25 trillion pieces of plastic debris in the ocean, from 269,000 tons afloat on the surface to some 4 billion plastic microfibers per square kilometer in the deep sea.

Plastic bags break up into smaller pieces, but their footprint never vanishes. If they do break down, it’s into polymers and toxic chemicals. Some 500 billion single-use plastic bags are used annually worldwide. If you joined them end to end, these petroleum pouches would circumnavigate the globe 4,200 times. Only a minuscule fraction are recycled or reused.

Twenty-five billion Styrofoam cups are thrown out annually in the United States alone.

A single tube of facial scrub can contain more than 330,000 plastic microbeads. A single microbead can be a million times more toxic than the water around it.

Nearly 3 million plastic bottles, every hour of every day, are used in the United States. Less than 30 percent are recycled.

More than 300 million plastic straws are used every day in the United States. Straws are too small to be easily recycled, so they typically become trash. Plastic straws are one of the top beach polluters worldwide.

Eight million tons of plastic are dumped into the world’s oceans every year.

About 100,000 marine creatures die every year from plastic entanglement.

About a million sea birds are killed every year by plastic. A record 276 pieces of plastic where found in one dead bird. It was 90 days old.

At least two-thirds of the world’s fish stocks are suffering from plastic ingestion.

A 2016 study warns that there will be more waste plastic, by weight, in the ocean than fish by 2050, unless humans clean up their act.

“We’ve plasticized the entire biosphere, including our bodies,” said Marcus Eriksen, research director and co-founder of the 5 Gyres Institute. “The impact of plastic is widespread, and it’s destroying the oceans.”

Eriksen was one of four guests who spoke March 4 at Brown University during a panel discussion titled “The Plastic Ocean.” The discussion also featured photographer Chris Jordan, Georgia State University professor Pam Longobardi and author Carl Safina.

In January, ecoRI News hosted a screening of A Plastic Ocean at the Cable Car Cinema, in Providence. Both events highlighted a serious problem.

Plastics production has increased twenty-fold since 1964, according to last year’s The New Plastics Economy: Rethinking the future of plastics study. Production is expected to double again in the next 20 years, and almost quadruple by 2050.

The world’s plastic problem was first identified in the 1970s. In 1987, a law was eventually passed to restrict the dumping of plastics into the ocean. The Marine Plastic Pollution Research and Control Act went into effect Dec. 31, 1988, making it illegal for any U.S. vessel or land-based operation to dispose of plastics in the ocean.

However, this act and other laws like it, such as the Microbead-Free Waters Act of 2015, can’t compete with mass consumption and throwaway societies.

In 2000, Eriksen traveled to Midway Atoll — a 2.4-square-mile island roughly equidistant between North America and Asia — where he found hundreds of dead Laysan albatross with plastic-filled stomachs. The visit narrowed Eriksen’s environmental focus, and led to the creation of his Los Angeles-based nonprofit that empowers action against the global health crisis of plastic pollution through science, art, education and adventure.

More than 600 animal species are impacted by plastic, through ingestion or entanglement, both of which can sicken or kill them, according to the 5 Gyres Institute. Birds, fish, turtles, dolphins, sharks and whales can be poisoned or trapped by plastic waste.

“There’s pieces of plastic out there with shark bites, turtle bites,” said Eriksen, noting that smaller pieces of plastic can be found everywhere in the world’s oceans. “The world is covered by microplastic particles. The fact we can find plastic in the middle of the ocean is a tragedy of the commons.”

Photographer Chris Jordan followed Eriksen to Midway Atoll. He has visited the far-flung island in the North Pacific Ocean several times. His photographs have vividly captured the destruction caused by plastic. The experience was soul-crushing.

Jordan, the first speaker at the recent panel discussion, introduced himself this way: “I’m the guy who took the horrible photos of the birds with plastic in their stomachs.”

As the Seattle-based photographer shot pictures and videos of plastic-ridden bird carcasses, he found himself sobbing. “Being with dying birds and seeing their suffering ... I felt the grief,” he said. “I never knew how much I cared about these animals.”

“We could be living in such a different way,” Jordan said. “There’s nothing standing in the way of radical change in global behavior. Science is telling us that we need this change.”

Pam Longobardi with some of the plastic she has collected from beaches around the world during the past 10 years. She makes art with some of it, to raise awareness of the world’s plastic problem, archives some of it and recycles as much of it as she can. (Drifters Project)

In 2006, after discovering mountains of plastic on remote Hawaiian shores, Pam Longobardi founded the Drifters Project. During the past decade, the nonprofit has removed tens of thousands of pounds of debris, mostly plastic, from the natural environment and reused the material as communicative social sculpture, to create awareness of the problem.

“The ocean ecosystem is full of life ... and it’s in trouble,” Longobardi told those gathered in the Brown University auditorium. “The ocean is vomiting plastic because it’s full.”

She called plastic a crime against nature, and noted that all this pollution is creating an environmental and racial crisis.

“Plastic comes back to haunt us,” she said. “It’s the ghost of our consumption.”

Longobardi has led “forensic beach cleanings” around the globe, from emptying plastic-filled caves on Kefalonia, an island in the Ionian Sea, west of mainland Greece, to scrubbing beaches in Hawaii. She’s currently running a project in Lesbos, a Greek island in the northern Aegean Sea off the coast of Turkey.

Change is possible, and the four speakers noted that, despite the best efforts of lobbying groups such as the American Chemistry Council, a tipping point is fast approaching.

For instance, applying circular economy principles to global plastic packaging flows could transform the plastics economy and drastically reduce negative externalities such as leakage into oceans, according to the 2016 report by the World Economic Forum and Ellen MacArthur Foundation.

“Why are we packing yogurt that lasts three weeks into containers that last forever?” Eriksen asked.

Individual behaviors are also changing.

“When I see a piece of plastic, I pick it up,” Longobardi said. “I know it won’t be consumed by a bird or animal.”

Frank Carini is editor of ecoRI News, where this first ran.