Todd McLeish: An early-warning system for toxic algae

Toxic algae in a “red tide.’’

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

When a large bloom of harmful algae appeared in lower Narragansett Bay in October 2016, and again in early 2017, Rhode Island’s testing methods weren’t refined enough to detect it before the toxins produced by the algae had contaminated local shellfish.

That scenario isn’t likely to happen in the future, now that the Rhode Island Department of Health’s laboratories have acquired new instrumentation and analytical tests to detect the toxins early and to determine when they have dissipated enough so shellfish harvesting may resume.

“It’s an improved early-warning system so we don’t have to worry about future problems with harmful algae blooms,” said Henry Leibovitz, the chief environmental laboratory scientist at the Department of Health. “We’re trying to safeguard public health, safeguard our shellfish economy, and safeguard the state’s shellfish reputation.”

The new testing system was approved in September by the Food & Drug Administration’s National Shellfish Sanitation Program, which regulates the interstate sale of shellfish.

The 2016 and 2017 blooms, which Leibovitz said were the first harmful algae blooms to occur in Narragansett Bay, forced the closure of parts of the bay to shellfishing and required that some previously harvested shellfish be removed from the market. It was caused by the phytoplankton Pseudo-nitzschia, which, when concentrated in large numbers, can produce enough of the biotoxin domoic acid to contaminate shellfish and cause those who eat the shellfish to contract amnesic shellfish poisoning.

Another kind of plankton, Alexandrium, produces a biotoxin that can cause paralytic shellfish poisoning. Both Pseudo-nitzschia and Alexandrium occur in Rhode Island waters year-round, but they are only harmful when concentrations are high and the toxins they produce reach 20 parts per million.

According to Leibovitz, the state’s previous testing system was “a primitive screening test” somewhat like a pregnancy test: it could determine whether the toxins had reached the limit, but not how far over or below that threshold they were. And it wasn’t sensitive enough to detect the lower concentrations of the toxins that would signal that the bloom had dissipated and shellfish harvesting could begin again. To reopen shellfish beds to harvest, the state had to send water and shellfish samples to a private laboratory in Maine, the only lab in the country capable of conducting the test at the time.

Now that Rhode Island has an FDA-approved lab, it’s offering its services to nearby states.

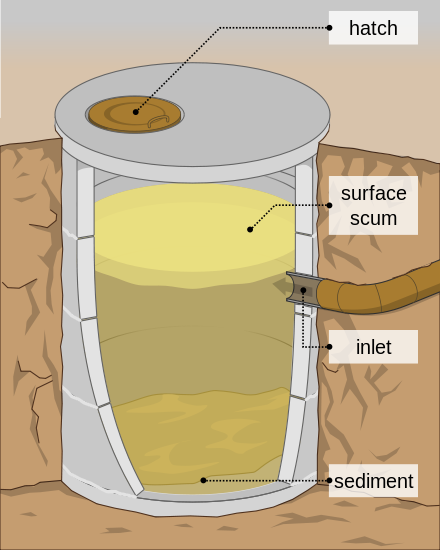

The state’s Harmful Algal Bloom and Shellfish Biotoxin Monitoring and Contingency Plan directs the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management to collect weekly water samples from areas of the bay where shellfish are harvested. The samples are tested in the Department of Health laboratory. If large numbers of harmful algae species are found, the plankton are tested to determine the concentration of toxins they are producing. If toxin concentrations are high, shellfish are then tested and a decision is made whether to close particular areas to harvesting.

The problem of harmful algae blooms has been an annual concern along the coast of Maine for many years, and scientists speculate that it could be a more frequent problem in southern New England in coming years, too.

“We think the problem is knocking on our door,” Leibovitz said, “and we need to be prepared for it, not only for public health but to protect our strong shellfish economy. Imagine the damage that would occur to our reputation if contaminated shellfish was identified as coming from Rhode Island. People have a long memory for something like that.”

Public awareness of the risk from harmful algae blooms was raised this year as a result of the months-long red tide in Florida, which killed fish and marine mammals and sickened many people. It was the result of a bloom of a plankton species that produces a toxin called brevetoxin, causing neurotoxic shellfish poisoning in people who eat infected shellfish.

What triggers the algae to bloom is what Leibovitz calls “the $60,000 question.”

“A lot of people are studying it, including some at the University of Rhode Island, and there are a lot of theories behind it, but there’s nothing conclusive. There’s speculation that the cleaner bay means that the harmful species don’t have the competition that they used to have, but that hasn’t been proven,” he said.

The bloom of harmful algae in Narragansett Bay in 2016 and 2017 led Rhode Island Sea Grant to fund research to try to answer some of the questions raised by the bloom. Researchers from URI and elsewhere are investigating whether bacteria that accompany the plankton may influence the amount of domoic acid produced; whether nitrogen from the sediments may fuel the blooms; and whether nutrients from outside the bay played a role.

“The fact that we had our first harmful algae bloom doesn’t mean we’ve had our last,” Leibovitz said, “not with it happening every year in Maine. But now we’ll be way ahead of the curve in recognizing when there’s a problem developing.”

Rhode Island resident and author Todd McLeish runs a wildlife blog.

Red tide rising

Red ride algae.

From Robert Whitcomb's "Digital Diary,'' in GoLocal24.com

Florida is sending us a warning about the fragility of coastal and other watery places in the face of over-development. Narragansett and Buzzards bays are particularly vulnerable.

On the southwest coast of the Florida peninsula a highly toxic bloom of red algae – aka, red tide -- is killing sea life, making breathing very difficult for humans and scaring away the tourists who fuel much of the region’s economy. The beaches are covered with rotting fish.

I’ve been on that very coast during a red tide, and it’s appalling. Residents flee indoors to get away from the aerosolized toxins from the algae, hoping that air-conditioning will clean out most of them.

Meanwhile, a different kind of algae – green stuff – continues to befoul inland lakes and canals.

Man is the main culprit. The vast quantities of fertilizers and other chemicals dumped on the state for agribusiness, housing-development lawns and golf courses end up in the water, where algae feed on them. Wetlands are filled in, land is paved over and innumerable canals are dug. All this means that much less of this polluted water can be absorbed and filtered by undeveloped land.

Rick Bartleson, a research scientist with the Sanibel-Captiva Conservation Foundation (named for two barrier islands along the southwest Florida coast known for their lovely beaches and sea shells), told The Washington Post that the region’s Lee County used to be 50 percent wetlands (and close to the Everglades). Now it’s 10 percent.

Warming water temperatures also play a role; the Gulf of Mexico now averages about two degrees warmer than it was in the late ‘70s.

Out-of-control development aided and abetted by local and state politicians well taken care of by those businesses has turned much of Florida, with its famous fresh-water wetlands, into a vast sprawl of unrestrained exurban and suburban development. Strip malls in the sunset.

The environmental devastation of this gold rush is unlikely to decrease anytime soon.

Llewellyn King: Trump swims in a cesspool of vengeance

Treating the products of the Trump administration.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Just when you think President Trump couldn’t sink any lower, he astounds. He’s bewildering in his ability to sink and then sink further -- and all the while to claim success, rectitude and leadership.

This week’s plumbing of the sewers of conduct came in two Trump specials.

First, there was the unbecoming amount of presidential time spent on denigrating Omarosa Manigault Newman. He knew her well -- knew her propensity for infighting, exaggerating and lying -- when he hired her on at the White House.

The question is, what was a reality show contestant of no particular ability doing in the White House to begin with?

Whether the president fired her, or his chief of staff did, doesn’t matter. Clearly, there was merit in getting her out of there. That’s now more than clear, when we learn that she was taping conversations in the Situation Room, the sacred heart of the White House.

After a firing, there’s a kind of protocol: You don’t litigate the issue ex post facto, especially in public. You let it rest; those who have been fired anywhere are usually aggrieved and angry.

The executive who did the deed doesn’t then sink into verbal mud wrestling with the dismissed person. One doesn’t do that. But Donald Trump does do that -- with relish.

More egregious was his yanking the security clearance of former CIA chief John Brennan. This is vicious, petty, vengeful and strikes at the very basis of civil respect in America.

Security clearances are, at the least, a kind of badge, a medal, a recognition that you have served the country at the highest level of trust.

I’ve known four secretaries of defense, five secretaries of energy, three CIA directors and 12 national laboratory heads. I’ve seen how those now carrying the burden of office have consulted with those who had carried it.

Those who have security clearance, even if they aren’t called upon to use their knowledge often, are a kind of national reserve of expertise in sensitive matters, ready when needed. Others may need security clearance in defense contracting jobs when they leave their government service.

We don’t have civil honors as in Britain. Those with security clearances carry a little honor, a little recognition — and a lot of pride.

While Trump was bearing his teeth against the defenseless, like a hyaena afraid of losing its prey, big stuff at home and abroad was what one would’ve thought might have been of commanding interest to the president, including:

· A red tide was damaging the ocean life of Florida while hurting its tourism.

· California was burning up with the worst fires in history.

· The mayhem was continuing in Yemen.

· Turkey, a NATO member, was being driven into the arms of Russia, while its failing currency was roiling world markets.

· Russia was believed to be preparing to knock out the U.S. electric grid; and it was legitimizing its grasp on Crimea.

· China was seizing the South China Sea.

Against these, and other domestic and world crises, Trump was lost to bile and spite.

A friend, a lifetime Republican (small government, fiscal restraint, free trade, strong defense) suggested in conversation this week that the Trump legacy would cost us a generation of lost opportunity in the world. He said it would take that long to get back to old alliances and to the position of respect we have enjoyed in the world.

I disagreed. I think it could take 100 years, perhaps. The rub is one never returns to the status quo ante after upheaval. The earth moves, so to speak.

Consider two historical events with 100-year legacies. The first is the Congress of Vienna, in 1815, which mapped a peace in Europe that lasted nearly a century. The second is the ill-conceived Treaty of Versailles, in 1919, the peace document signed at the end of World War I. It led to World War II; and, to this day, it’s at the root of much of the trouble in the Middle East.

Tweeting isn’t communicating, settling scores isn’t governing, handing the world over to Russia and China isn’t what we expect of any president, even a petty one awash in bile.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com. He's based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.