Retreating looks wiser than rebuilding on the coast

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

There’s intensifying debate in many coastal and other areas that are increasingly flood- and erosion-prone in our warming climate on whether we should repeatedly repair or replace flood-damaged structures; have taxpayers pay some or all of the cost to move them to higher ground, and what to put in their place. I think the obvious answer in many places is to retreat and create flood-mitigating parks with (new?) marshes and thick vegetation and other water-absorbing materials that can reduce damage to the higher-elevation properties nearby. Of course, in such densely built urban areas as Newport’s Point neighborhood and Boston’s Seaport District that’s tricky.

I thought about this the other day when reading about the debate in Newport over whether to abandon the idea of rebuilding storm-damaged facilities at Easton’s Beach and stage a retreat. It seems clear to me that given projections of continued global warming and associated sea-level rise, that spending money to rebuild the Easton’s Beach amenities would soon be seen as a waste of money. Replenishing the sand that storms have washed away is expensive enough, though needed to keep the beach as a major attraction for locals and tourists alike.

Forecasts for the 2024 hurricane season are starting to come out. It looks, er, exciting.

Measuring CO2 in the Ocean

Edited from Wikipedia caption: “This diagram of the fast carbon cycle shows the movement of carbon among land, atmosphere and oceans. Yellow numbers are natural fluxes, and red are human contributions in gigatons of carbon per year. White numbers indicate stored carbon.’’

Thank you, Paul Salem, for giving the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) $25 million for ocean research in general and, in particular, to study the oceans’ capacity for removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, into which we’ve been putting vast quantities of climate-warming CO2 by burning fossil fuels, clear-cutting forests, degrading wetlands and engaging in industrial agricultural practices (especially large-scale livestock production). The heating of our climate is accelerating, and more than 70 percent of the world’s surface is ocean.

Note that this excess carbon dioxide is also acidifying the water, harming sea life.

Mr. Salem, a billionaire, was a partner in Providence Equity Partners, and in 2022, he became chairman of WHOI’s board.

WHOI president Peter de Menocal said: “There is a tidal wave of ‘blue carbon’ solutions to climate change on the horizon, some proven, but most completely novel and in need of testing to investigate their safety and effectiveness. The ocean can help us avert a climate crisis, but we need to also ensure the long-term health of marine ecosystems and the communities that rely on ocean resources. This far-sighted gift {by Mr. Salem} will help us stay ahead of what is already a billion-dollar industry and inject some much-needed reality into the carbon market.”

xxx

I have always had a soft spot for Woods Hole, because this windswept village, basically a kind of college town within Falmouth, is so beautiful and dramatic; because of WHOI and other marine-related institutions based there, and their smart and interesting people, and because an important part of my father’s family lived in and around it. Some moved there in the 17th Century when, as Quakers, they fled Puritan persecution in and around Boston, and others came down from the Boston area as summer people when trains were extended to Cape Cod in the 1870’s. There were more than enough eccentrics among them; some had weird whirligigs on their roofs and some were recluses.

View of downtown Woods Hole, including Marine Biological Laboratory and Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution buildings.

Why sea-level rise is highest here

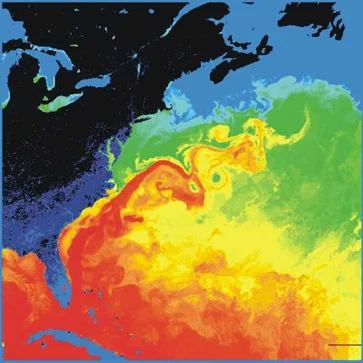

Surface temperatures in the western North Atlantic. The North American landmass is black and dark blue (cold), while the Gulf Stream is red (warm). Source: NASA

Via ecoRI News (ecori.org)

Why is the Northeast experiencing higher levels of sea-level rise than other parts of the wold? Area scientists attribute it to two factors: a slowdown in the Gulf Stream and the melting of ice sheets in Antarctica and Greenland.

The slowdown of the Gulf Stream is complicated, and conclusions for the cause have varied. The consensus cause is the warming of the North Atlantic. What is still being debated is the effect of the influx of fresh water. Nevertheless, the warming water is creating a “traffic-jam scenario” in ocean circulation. The slowdown causes offshore sea levels, which are higher than coastal sea levels, to flatten and send water inland to regions such as the Northeast.

“Picture a banked turn in a racetrack,” said Bryan Oakley, assistant professor of environmental geoscience at Eastern Connecticut State University. “As the circulation slows, this causes the slope to decrease, and as the water level goes down along the Gulf Stream, the water level will rise along the coast — two ends of a seesaw, so to speak.”

Melting ice is also pushing water our way. As ice sheets in Greenland liquefy, they lose their gravitational pull and, therefore, ocean water that was drawn to the icy masses instead flows into the southern hemisphere. The same phenomenon is happening as the Antarctic losses ice, this time the water is redirected toward the Northeast.

There is yet another cause of higher regional waters. John King, professor of oceanography at the University of Rhode Island’s School of Oceanography, said warming water in the North Atlantic may halt or slow the natural cool-water vacuum that draws warmer coastal water out to sea.

All of these factors have led the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to project a maximum sea-level rise of 11.5 feet by 2100.

“Currently, about 6 million Americans live within about six feet of the sea level, and they are potentially vulnerable to permanent flooding in this century,” said Robert E. Kopp, an associate professor at Rutgers University’s Department of Earth and Planetary Science, who co-authored the recent NOAA report. “Considering possible levels of sea-level rise and their consequences is crucial to risk management.”

Those consequences to natural habitats include increased beach and marsh erosion.

In Rhode Island, there are about 7,000 people living within the 7-foot sea level-rise inundation zone, according to a Statewide Planning report.