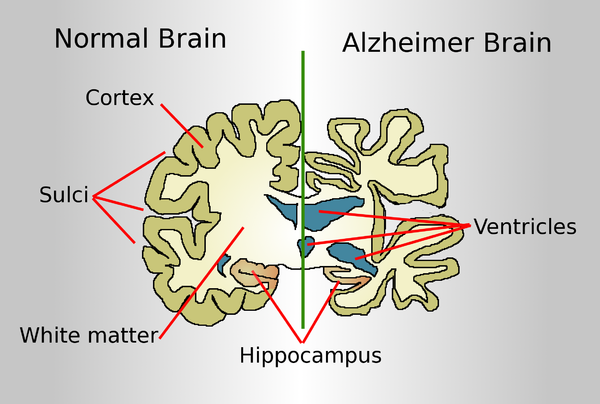

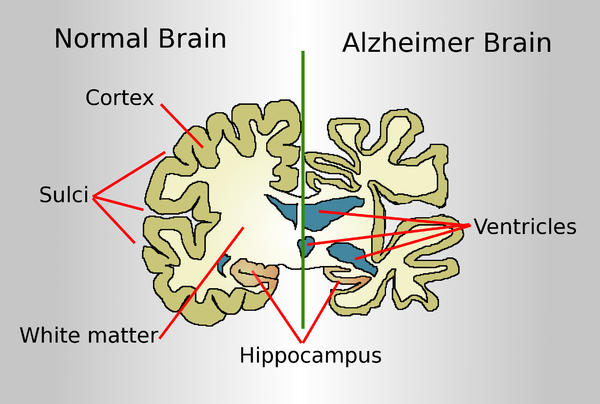

A normal brain on the left and a late-stage Alzheimer's brain on the right.

The Food and Drug Administration’s approval in June of a drug purporting to slow the progression of Alzheimer’s disease was widely celebrated, but it also touched off alarms. There were worries in the scientific community about the drug, developed by Cambridge, Mass.-based Biogen, mixed results in studies — the FDA’s own expert advisory panel was nearly unanimous in opposing its approval. And the annual $56,000 price tag of the infusion drug, Aduhelm, was decried for potentially adding costs in the tens of billions of dollars to Medicare and Medicaid.

But lost in this discussion is the underlying problem with using the FDA’s “accelerated” pathway to approve drugs for conditions such as Alzheimer’s, a slow, degenerative disease. Though patients will start taking it, if the past is any guide, the world may have to wait many years to find out whether Aduhelm is actually effective — and may never know for sure.

The accelerated approval process, begun in 1992, is an outgrowth of the HIV/AIDS crisis. The process was designed to approve for sale — temporarily — drugs that studies had shown might be promising but that had not yet met the agency’s gold standard of “safe and effective,” in situations where the drug offered potential benefit and where there was no other option.

Unfortunately, the process has too often amounted to a commercial end run around the agency.

The FDA explained its controversial decision to greenlight the Biogen pharmaceutical company’s latest product: Families are desperate, and there is no other Alzheimer’s treatment. Also, importantly, when drugs receive this type of fast-track approval, manufacturers are required to do further controlled studies “to verify the drug’s clinical benefit.” If those studies fail “to verify clinical benefit, the FDA may” — may — withdraw them.

But those subsequent studies have often taken years to complete, if they are finished at all. That’s in part because of the FDA’s notoriously lax follow-up and in part because drugmakers tend to drag their feet. When the drug is in use and profits are good, why would a manufacturer want to find out that a lucrative blockbuster is a failure?

Historically, so far, most of the new drugs that have received accelerated approval treat serious malignancies.

And follow-up studies are far easier to complete when the disease is cancer, not a neurodegenerative disease such as Alzheimer’s. In cancer, “no benefit” means tumor progression and death. The mental decline of Alzheimer’s often takes years and is much harder to measure. So years, possibly decades, later, Aduhelm studies might not yield a clear answer, even if Biogen manages to enroll a significant number of patients in follow-up trials.

Now that Aduhelm is shipping into the marketplace, enrollment in the required follow-up trials is likely to be difficult, if not impossible. If your loved one has Alzheimer’s, with its relentless diminution of mental function, you would want the drug treatment to start right now. How likely would you be to enroll and risk placement in a placebo group?

The FDA gave Biogen nine years for follow-up studies but acknowledged that the timeline was “conservative.”

Even when the required additional studies are performed, the FDA historically has been slow to respond to disappointing results.

In a 2015 study of 36 cancer drugs approved by the FDA, only five ultimately showed evidence of extending life. But making that determination took more than four years, and over that time the drugs had been sold, at a handsome profit, to treat countless patients. Few drugs are removed.

It took 17 years after initial approval via the accelerated process for Mylotarg, a drug to treat a form of leukemia, to be removed from the market after subsequent trials failed to show clinical benefit and suggested possible harm. (The FDA permitted the drug to be sold at a lower dose, with less toxicity.)

Avastin received fast-track approval as a breast cancer treatment in 2008, but three years later the FDA revoked the approval after studies showed the drug did more harm than good in that use. (It is still approved for other, generally less common cancers.)

In April, the FDA said it would be a better policeman of cancer drugs that had come to markets via accelerated approval. But time — as in delays — means money to drug manufacturers.

A few years ago, when I was writing a book about the business of U.S. medicine, a consultant who had worked with pharmaceutical companies on marketing drug treatments for hemophilia told me the industry referred to that serious bleeding disorder as a “high-value disease state,” since the medicines to treat it can top $1 million a year for a single patient.

Aduhelm, at $56,000 a year, is a relative bargain — but hemophilia is a rare disease, and Alzheimer’s is terrifyingly common. Drugs to combat it will be sold and taken. The crucial studies that will define their true benefit will take many years or may never be successfully completed. And from a business perspective, that doesn’t really matter.

Elisabeth Rosenthal, M.D., is editor of Kaiser Health News.