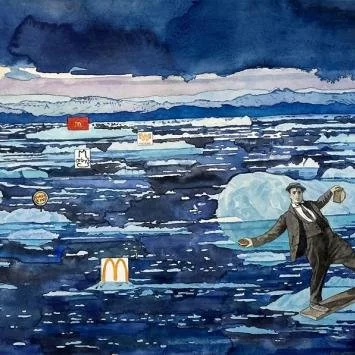

Text and watercolor painting by William T. Hall, a Florida-and-New England-based painter and writer

As we endured one of our family weeding sessions in our vegetable garden in Thetford, Vt., my grandfather said abruptly, and with strong emphasis, the four-letter “S-word”. It was enough of a surprise to lead grandmother to remind him that children were present. “Jesus, Mary and Joseph, Harold, your language – please!”

We all stared at Gramps as Grandmother looked over her glasses at my mother, who was smiling at her while fighting with a deep-set weed. Mother’s garden glove was full of a dozen or so vanquished weed specimens dropping dust as she looked over to me, rolling her eyes. I could see my reflection in her sunglasses as my little brother, Steve, leaned in and whispered to me , while wagging his index finger at the ground, “Naughty-naughty, Gramps”

“What’s wrong, Dad?” my mother asked. “You okay?”, she asked, as she pulled on another stubborn weed.

He said nothing as he set his jaw and unfolded his tall frame upward from his kneeling position like a camel standing up in the desert. He was looking at the top of his wrist as if to check a watch that wasn’t there. In that hand he held a big red Folger’s coffee can half-filled with kerosene into which he had been dropping hundreds of Japanese Beetles. These he had picked meticulously from the leaves of his potato plants. This sort of thing defined one of his methods for guarding against pests in the modern age of pesticides. “Better to pick’m off and get’m before they get you.”

After he had stood up fully, he looked perplexed, as if he didn’t believe what had just happened. He looked at my grandmother and said one word,

“Bee.”

“Sting?“ My mother asked.

“No he just scratched me a — warning”.

This we all knew from being on the farm. When you work around bees they are busy, too, gathering honey. Unless you create too much commotion around bees or otherwise make them too anxious, a human usually gets a (warning) a scratch before a (sting).

A warning was when a bee dragged his stinger across your skin to give you what felt like a little hot spark. A full “sting” was, of course, much more painful and was delivered with a bee’s ultimate strength, resulting in the hooked end of the stinger deep under the skin with the bee’s abdomen still attached to feed the stinger with venom. This added to your pain immensely. For this one extreme act, the honeybee pays with its life, and for allergic recipients, the sting can cause anaphylactic shock. To that person multiple stings all at once could cause death.

To my grandfather this “scratch” seemed like an unprovoked over-reaction, and he didn’t understand what he had done to deserve it.

Harold had been stung several times in his life but he understood that each time he’d done something provocative. When he saw that there were lots of other bees around us not harming us, it seemed as if nothing menacing had happened, so what was the big deal? Grandpa was insulted. He shook his head. My mother, teasing her father, asked him, “Dad, did you make a mistake? You know the difference between a Japanese beetle and a bee right”?

We all laughed and looked at my grandfather, wanting to gauge his reaction to my mother’s tease. He held the coffee can in one hand and laughed politely at the ribbing. He was always a good sport.

“I’m glad I didn’t sit on him”, he said and got a double-good laugh from all of us.

But as he was looking at us he was still wondering why there seemed to be so many bees everywhere in the air. They swirled like embers from a campfire. It was a busy confusion in orange, black and tan reminding him of when he attended his mother’s beehives at their turkey farm in Walpole, Mass., years before.

“Gramps! What’s is that?” asked my brother Steve he excitedly pointed to the sky above and behind Gramp’s silhouetted upper torso.

“Harold!” My grandmother shouted sharply, my grandfather and the sky above him reflecting in her glasses.…

Gramps looked at her perplexed as he turned to see what she meant. Something amazing and frightening was happening in the sky behind him. He had never seen anything like it before, and nor would he ever again. He looked back in awe at a jet-black roiling cloud in the sky over the Connecticut River. “It’s bees!”Then suddenly,“ SWARM!” he yelled as he set down his coffee can.

“What the heck!?” My mother exclaimed as she stood up, dropping her spade and the weeds from her gloves.

“Gloria, Quick help me up!” my grandmother yelled. My mother said frantically, in a commanding voice, to Steve and me, “Kids, get your grandmother up and head to the house”! As we helped our 200-pound grandmother to her feet, our mother rushed to her father’s side asking. “What should we do? Dad?”

They both looked up at the cloud and now we all could hear the sound of the bees, which mimicked the sound of a breeze blowing through tree leaves.

My grandfather mumbled something unintelligible in Swedish under his breath.

“Pop, in English!”, my mother asked in a slightly panicked tone. “What should we do?”

Without taking his eyes off the swarm, Gramp said, “Yes, get Lillian to the house, but don’t run, Ok? Just walk fast and don’t panic. We must not spook the swarm. Look at them! They look pretty riled alread.”

“Harold, you be careful,’’ my grandmother said.

“We’ll be fine, ’’ he said.

“Somewhere in the middle of the swirling mass is the Queen. Bees will do anything to protect their Queen. They’re looking for a new hive. These other bees down here are the scouts”.

Our farm was on the floor of Vermont’s Upper Connecticut River Valley about a football field’s length from the river and a mile’s south of the village center of Thetford. Our barn was in the middle of our property between two 25-acre fields, with two big shade-maple trees taller than any other trees next to the barn, which was four stories tall, from the basement to the peak of the open hayloft.

The whole barn structure was basically open. It was June, and the barn was empty of hay. There was one window in the peak and an open hay door in the end. The barn was designed to suck air in at the basement pig stalls on the backside of the building and to direct it inward and upward out through the big open barn doors and hay doors in both peaks. Those doors were 16 feet tall and were at the top of the earthen ramp that led to the second story. The ramp was designed for horses pulling full hay-wagons up into the big main hay-storage room. The main room was enormous, about 40 by 60 feet and 45 feet to the peak, where the hay trolley track and unloading-fork still hung covered in cobwebs.

Grandpa knew that the swarm of bees high in the air above our barn probably saw what looked like the perfect place for new beehive — a place with the perfect size and shape to house what seemed like a zillion tired and desperate bees and their queen.

My grandfather could see this in the few moments he had to scope out the problem and he understood that the welcome mat would be out until he could close up the barn to keep out these unwelcome guests.

Gramps now could hear the house windows being slammed down shut and the garage door being closed in the long shed off the main house. The ladies had done their job. The house would be a secure hiding place for the family no matter what happened in the other buildings. Grandpa’s carpentry shop, the hen house, a little stone milk-house and our barn were the only possible manmade homes for the bees.

The area directly above and behind the barn was a jet-black fuzzy moving mass. The swarm covered the whole width of the house, barn and shade trees. The scene reminded Gramps of the sand-and-soil clouds during the 1930’s Dust Bowl. Like those roiling clouds, the cloud of bees had a dark and menacing look.

Like a monster in the sky, the cloud seemed to lurch forward, north up the river, and then roll back on itself down the river as if there was dissension in the cloud of bees.

The air around us was still filled by a blizzard of bees, but even though we were occasionally scratched by the frantic scouting insects, we did not feel in danger. We could see their dilemma. We did not want to make their plight any worse than it was, but they could not have our barn, from which it would have taken months and lots of money to dislodge them. Worse, many bees would die in the removal. Maybe the bees could feel this, or maybe they were totally unaware of us, but they continued to leave us alone.

Gramps knew that with any flood of living things — humans, cattle, turkeys, fish and so on, only so many of them could get through a restricted opening at once without catastrophic results.

They had only their instinct to protect and nurture their queen. Each individual bee was devoted to its queen first, then secondly to the whole hive. Beyond that simple reality they had not evolved.

They were incapable of leaving her but confused about where to take her. At this point they seemed at a crossroads.

“Billy, go to the basement of the barn and close all the pig-pen doors down there,’’ Gramps told me. “Make sure the bees can’t get through any cracks. Throw hay at the bottom of the doors to close up the gap. Then meet me at the front ramp and we’ll close the big doors together. We can get to the windows last. Listen to me.…If this all turns bad, then get to the house and your mother will know what to do”.

“Where are you going, “ I asked.

“I’ll go to my shop and see if I can close it up. It’s wide open”.

“What about the chickens,” I asked.

“I don’t know? They eat bugs. They’ll have to fend for themselves”.

The cloud of bees was hanging over the rear pasture and getting closer to the barn by the minute, casting a dull shadow as when a cloud causes a shadow in the valley. I did get stung when I closed the last pig-pen door and I put my hand right on a bee. It hurt, but I sucked on the spot and kept moving.

When I got to the big doors in the front of the barn, grandfather was there. He’d rolled the burn-barrel up the ramp, saying that would be a last resort. He would start a smudge fire in the barrel to smoke out the incoming bees if it became necessary. The thought of any open fire in our barn made us both sick to think about. “Would you really risk that”, I asked my grandfather.

“No. I don’t think so, but we’ll see”.

As we rolled the barrel into place, something in the changing sky caused a shift on what had been sun-lit ground to scattered shadows there. With that change came a slight drop in temperature.

The moment seemed to signal something within the swarm. The bees moved. They roiled northward, and then suddenly their pace increased and they seemed to rise up farther. There was a bulge in the front of the cloud as it headed up river. The swarm passed over the iron bridge a half mile away at East Thetford and continued headed north, up the river. Where there had been millions of scouting bees at our farm, in a few minutes there were none.

The swarm eventually disappeared into far northwestern New Hampshire, where they were believed to have taken up residence in the stacked-up wrecked automobiles in a large junkyard abandoned years before, and then, finally, in spectacular Franconia Notch.

Little by little, one of those companies that catches and ships bees were able to capture many of the insects and transport them to areas of the U.S. that suffered from a deadly fungus that still endangers bee populations today.

Where the bees came from in such large numbers and why they took flight has never really been determined.