From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of the New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

New Hampshire is known not only for its rugged mountains, rocky 19-mile shoreline, one of the largest legislative bodies in the world and its in-your-face Live Free or Die license plate motto. It is also home to the first-in-the-nation presidential primary, the Free State Movement, more voters who register as “unaffiliated” (independent) than either Republican or Democrat, one of the highest income and educational attainment levels in the country, one of the lowest child poverty rates, the second-highest opioid overdose death rate, and in recent years, the fastest growing rate of income inequality, according to federal data.

New Hampshire is one of five states with a median age greater than 42. The rate of population growth among immigrants matched the U.S. average of 9% from 2010 to 2016, according to a Migration Policy Institute analysis of U.S. census data. If New Hampshire had an official state dinosaur, it would be Barney, reflecting the purple nature of our political culture. We currently have a solidly Democratic Congressional delegation and a solidly Republican Legislature and governor. With no sales or income tax and 234 discrete municipal entities, New Hampshire is a highly decentralized state with a long tradition of local control, reliance on local property taxes to fund public services and suspicion of those who are “from away.”

As we have reported in the Civic Health Index, the state ranks relatively high in civic participation, although patterns of inequity are evident with respect to gender, social class, educational level and age. The tradition of annual town meetings to set municipal and school district budgets continues in smaller communities, but the number of residents who attend and the participatory nature of the meetings have declined significantly in recent years thanks to their increasingly contentious nature and changes in state laws that have incentivized written balloting over deliberation and voice votes.

In short, New Hampshire is a place of both traditions and contradictions. Though historically New Hampshire’s demographics have been primarily white, the state is becoming increasingly diverse with respect to racial and ethnic identities.

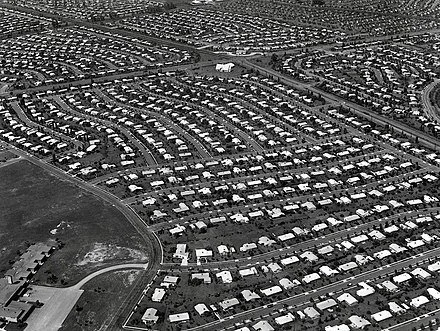

There are communities with significant wealth adjacent to towns with widespread poverty and devastating rates of addiction. As a report from the New Hampshire Center for Public Policy Studies described it, there are increasingly “two New Hampshires,” one made up of rural communities with scarce public infrastructure, aging populations and shrinking employment opportunities, and one comprising more densely populated areas characterized as more diverse, metropolitan, economically vibrant and attractive to millennials and their young families.

About New Hampshire Listens

These distinctions and contradictions have provided fertile ground for New Hampshire Listens, which we founded in 2009 in response to the growing polarization of political and civic discourse, the severe economic challenges of the Great Recession that were causing disruption and strife in many communities across the state, and a growing consensus among community leaders and activists that new approaches to community problem-solving were sorely needed. Inspired by the success of Portsmouth Listens, our predecessor and prototype established in 1998, the mission of NH Listens is to help people talk and act together to create communities that work for everyone.

New Hampshire Listens is a civic-engagement program within the University of New Hampshire’s Carsey School of Public Policy, but derives its funding primarily through grants or contracts with organizations and municipalities in exchange for engagement support. Since 2010, we have hosted conversations in more than 85 towns and cities, engaging some 4,500 New Hampshire residents in small groups for facilitated dialogue on a wide range of issues (including land use, community-police relations, public school reform, youth engagement and substance-use disorders, as well as other topics).

We support a growing group of Local Listens affiliate organizations led by community leaders in diverse locations across the state. Local Listens affiliates are locally run public engagement groups that are independent of NH Listens but commit to following our core principles, which include bringing people together from all walks of life; providing time for in-depth, informed conversations; respecting differences as well as seeking common ground; and achieving outcomes that lead to informed community solutions. Local Listens groups work within their communities to address regional and statewide challenges and create their own public engagement approaches or draw from NH Listens open-source online tools and templates.

NH Listens is “issue agnostic” and committed to impartial facilitation as a third-party convener whose role is to help others have productive, civil and inclusive conversations. NH Listens collects data on key research interests in the participatory democracy field reflected by our three main goals: engaged and equitable communities, increased participation in public life (especially for those who have historically been disenfranchised), and improved community problem-solving.

As a civic-engagement resource located in a university, we also work with students and faculty through on-campus dialogue to address such complex issues as free speech, gender and racial discrimination, behavioral health, postsecondary admissions policies and the challenge of affordability. For example, in the 2017-18 academic year, we designed and conducted a series of dialogues for the faculty and staff of the College of Health and Human Services at the University of New Hampshire focused on creating an equitable and just community, in classrooms, department offices, internship sites and research centers. We are now partnering with the Department of Communication’s Civil Discourse Lab to support undergraduate curriculum and train students in facilitation for public conversations. For the past several years, we have worked closely with the associate vice president for community, equity, and diversity to design campus-wide dialogues around inclusion and equity, both as a proactive strategy and in response to specific incidents of identity-based harassment or threat.

Conceptual frameworks and core values

We have been inspired by two particular frameworks articulated by colleagues at Harvard’s Kennedy School and MIT’s School of Urban Studies and Planning. Archon Fung, dean of the Kennedy School, in his 2015 article on rationales for increased participation in governance, emphasized the importance of legitimacy, effectiveness and social justice. Fung argues that, “the strongest driver of participatory innovations has been the quest to enhance legitimacy. The hope is that such innovations can increase legitimacy by injecting forms of direct citizen participation into the policymaking process because such participation elevates perspectives that are more closely aligned with those of the general public and because that participation offsets democratic failures in the conventional representative policymaking process.”

Likewise, effectiveness is enhanced when more, and more diverse, voices are engaged in the processes of community problem-solving. Fung claims that, “By reorganizing themselves to incorporate greater citizen participation, public agencies can increase their effectiveness by drawing on more information and the distinctive capabilities and resources of citizens.” Finally, social justice aims are approximated, “when participatory governance reforms successfully incorporate people or views that were previously excluded, [thus increasing] equality by enabling them to advocate more effectively for goods and services, rights, status, and authority.”

NH Listens has increasingly placed equity at the center of our design strategies and community organizing as we work with local and state leaders on specific initiatives. We cultivate approaches to racially equitable engagement in partnership with Everyday Democracy, based in Hartford, Conn. Everyday Democracy works nationally to conduct dialogue and engagement with an explicit “racial equity lens” that acknowledges how effective community policy and practice must pay careful attention to the ways in which historic and contemporary racism affect decisions, and to design engagement to ensure people of color have voice and power at the decision-making table. As New Hampshire has seen increased income inequality and become more ethnically and racially diverse, we have explicitly emphasized the value of racial equity in our work.

To this end, we have established a statewide network of “NH Listens Fellows” who have expanded the range of social identities, geographic representation and expert capacities of our staff. These Fellows work on specific projects depending on topic, availability and funding sources. We have also partnered with the Endowment for Health in New Hampshire, a foundation concerned with health and health disparities, over the past several years to offer intensive workshops for leaders across the state and across sectors who are in positions to create more equitable and inclusive communities and organizations. Understanding their own identities, the effects of implicit bias and structural racism, and their responsibilities and opportunities as leaders who hold power and privilege is at the core of this ongoing effort.

The second framework that affirms our commitments to more equitable and robust civic engagement comes from Ceasar McDowell at the Civic Design Lab at MIT. McDowell identifies six types of “conversations essential for democracy.” These include:

1. Framing, or creating a shared understanding among stakeholders of the definition and elements of the problems or challenges to be addressed;

2. Ideation, or the generation of possible solutions to those challenges;

3. Prioritizing, in which value choices are deliberated and weighed;

4. Selecting, which requires finding some common ground among participants to agree on a path forward;

5. Implementing, when talk becomes action and participants work with decision-makers and those in authority to put recommendations in place; and

6. Monitoring, to be sure that those who are implementing the outcomes of engagement processes are held accountable.

We have found that these essential elements mirror the arc of the engagement and public conversation processes developed by NH Listens over the years. The majority of effort we put into achieving our mission looks more like community organizing and mobilizing than face-to-face deliberation per se. Bringing people together for meaningful and inclusive deliberation requires intensive work with community partners over time. From the first conversation with potential partners, our purpose is to facilitate, not prescribe, possible solutions or ultimate selection of a path forward. We bring an array of tools; community partners select the ones that make the most sense for their specific circumstances. In the past few years, we have increased attention to coalition-building among diverse local partners and organizations as a necessary condition for meaningful and effective engagement. We have found that it is especially important for a third-party convener to support coalition-building processes in order to avoid territorial and competitive behavior that often is associated with well-meaning efforts led by an existing community organization or municipal entity.

All this is not meant to imply that we are neutral about our work. Being impartial about means and ends is not the same as being neutral about the essence of engagement and deliberation. We are deeply committed to democratic practices that include all voices and amplify those that have been traditionally ignored or suppressed. It is not unusual for local organizers to overlook the importance of bringing diverse and previously disenfranchised voices to the table, not due to willful neglect but more often due to a lack of experience and a certain degree of myopia when it comes to taking seriously the views and experiences of those with whom they are unfamiliar.

NH Listens / Concord

We have found that democratic practices that emphasize equity in both input and outcomes lead to more legitimate and effective solutions for everyone. For example, beginning in 2018, NH Listens has been working with a city in the northern reaches of the state (“north of the notches”) to support broad community engagement regarding the future of the community’s public schools. The district is fast approaching a significant funding crisis, as enrollments decline (typical of economically challenged rural communities) and the state’s education appropriations continue to decline.

The situation strikes several deep nerves related to community identity, local taxes, educating and retaining the next generation, and core values rooted in the past and present as well as hopes for the future. It is imperative that all voices be heard in the engagement processes being used to find a path forward. Elderly people on fixed incomes, employers, students and their parents, educators, newcomers as well as multi-generation residents, those with low incomes as well as the wealthy all have a stake in the conversation and its outcomes. On the output side, solutions will need to address the needs and interests of all stakeholders, especially those residents who depend most on public education to open doors to greater economic and social opportunity.

As impartial conveners, we must set aside our own biases about preferred solutions and work to be sure that all voices are heard, especially those that have historically been silenced because of weak economic power or low social standing. And we must work to frame the conversations in collaboration with our local partners to ensure that recommendations for action take into consideration the needs of all members of the community.

Is NH Listens making a difference?

Skeptics could point out that the degree of polarization and uncivil discourse in New Hampshire (like other places) has only increased since we began nine years ago. Incidents of racial harassment among both youth and adults have increased, particularly since November 2016. We have witnessed a significant increase in requests from schools and communities for assistance in organizing difficult conversations about race and racism over the past two years. According to a recent report from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, New Hampshire’s opioid crisis has gotten worse, with overdose deaths tripling from 2013 to 2016. Public schools in smaller cities and many rural communities face constant threats to their fiscal survival as property tax payers fight over teacher contracts and addressing capital expenses.

At the same time, in a range of efforts we have supported, we can document qualitative improvements in the willingness of community leaders to take on the most pressing challenges, including: the need to provide affordable and safe housing; the critical importance of engaging youth in ways that make them feel respected and valued; the benefits of providing accessible and high-quality early education to all young children; the need to strengthen collaborations among schools, families and community leaders; and the urgency of ensuring respectful relationships between local police forces and everyday citizens, especially youth, residents of color and New Americans. These are examples of topics we have worked on at the local, regional, and state level in recent years. In each case, we have seen that carefully framed and facilitated inclusive deliberation can lead to changes in practice and policy.

In the community of Pittsfield, N.H., NH Listens worked with the school and community to create a series of dialogues about school improvement. Pittsfield had been ranked one of the lowest-performing schools in the state in 2010, and there was low community pride and disengagement about its schools. In 2011, NH Listens trained local facilitators who then engaged over 100 Pittsfield stakeholders, including students, parents, community members, teachers, school administrators, municipal and business leaders about how we can make Pittsfield a better place for everyone to live, learn, work and play. From these community conversations and other engagement activities, school leaders compiled recommendations for school change into a grant application to the Nellie Mae Education Foundation, and Pittsfield was awarded $2 million to undergo a shift toward student-centered learning.

What resulted were school policy changes such as restorative justice as a disciplinary measure, a formal school-funded position of “school-community liaison,” who works to connect the schools and the community, and a new middle and high school governance body that works to shape school policy alongside the school board. There were also measurable shifts within the community. The Pittsfield Youth Workshop, an afterschool drop-in center for local youth, created a program called Pittsfield Listens, which was an affiliate of NH Listens and committed specifically to engaging youth, parents, community members about education and youth issues in Pittsfield.

Pittsfield Listens established a civic-education series to inform community members about how to use local government structures such as the school board and town select board, and worked with the Chamber of Commerce to encourage candidates running for local office to engage in small group dialogue with community members about their stance on issues in Pittsfield, rather than delivering their stump speeches on a microphone at the community. Pittsfield has recently been written about by the Atlantic and other news outlets of a national model of school transformation. The U.S. Department of Education sent staff to Pittsfield to observe its success and the NH Education commissioner and governor also paid visits to learn from the Pittsfield schools. What Pittsfield exemplifies is that when communities and institutions are willing to dive into deep, deliberative engagement processes, such processes can stimulate community change at multiple levels.

Such changes in practice and policy typically reflect the common ground that emerges when people come together to solve the problems they face. When community members use deliberative tools to explore values, data and alternative pathways, solutions are generated that reflect concrete needs and circumstances, not ideological positions or the influence of special interests. These findings corroborate the emerging national conversation advanced by James and Deborah Fallows in Our Towns and the concept of Constitutional localism described recently by Mike Hais, Doug Ross and Morley Winograd in Healing American Democracy: Going Local, and advanced by Thomas Friedman, David Brooks and others on both the right and left who see that bottom-up approaches are critical at a time when faith in top-down solutions has gone missing.

We also have seen that the call for civic and civil engagement through deliberative democratic processes is being advanced by leaders in New Hampshire who are aligned with philanthropic, nonprofit, corporate and government sectors. Through participation in various NH Listens initiatives, these leaders are more likely to prioritize civil discourse, strengthened civic infrastructure and the enfranchisement of those whose voices have often not been heard. We don’t take credit for these shifts, but we do know that when everyday citizens, stakeholders and local and state leaders together experience authentic and sustained dialogue, they consistently ask for more opportunities such as those we design and regularly cite the value of this approach to strengthening public life.

Looking to the future

Given the nature of our mission, NH Listens is more responsive than proactive in deciding what community challenges to address. We do not decide what is ailing communities nor what communities need in order to do better by way of public life. We help communities respond to the challenges they identify and define. In that sense, it is not easy to predict which issues or topics we might engage with in the coming years. However, we can see some constant threads that are likely to run through the work in the future.

We place value in youth and schools for several key reasons. Other than public libraries, public schools are one of the few open public spaces in many communities, particularly in the more rural locations our state. It is critically important to all communities, and to the preservation of democracy in general, for youth and young adults to feel they belong and that their voices count. Efforts to support youth and young adult engagement as volunteers, members of governance boards, voters and leaders will be core to the work of deliberation and community development. Second, public schools are very likely to continue to be contested spaces, whether the issue is what should be taught, how it should be taught, who should teach, what kinds of facilities are needed and how (and how much) to pay for public education. We expect to be active in helping schools and their communities form effective, close partnerships for the foreseeable future. Much of this work will be about weighing the need for expert judgment on the part of educators with the values and priorities of everyday citizens who have the biggest stake in what their children learn and how they learn it.

There is interest in taking the NH Listens experience to neighboring states. We are now exploring what that could look like with colleagues in Maine and Vermont and perhaps the wider New England region. Each New England state is certainly unique in its culture and politics; for instance, as Harvard sociologists Kaufman and Kaliner argue in their 2011 Theory and Society article, New Hampshire’s low taxation and small government has attracted hunters, fishers, Boston commuters and motorcyclists, whereas Vermont’s progressive experimental colleges have impacted its left-leaning political activism ethos. Since the NH Listens approach encourages listening to communities and responding to the issues communities identify, such flexibility could be helpful in cultivating engagement networks in other New England states. However, marked similarities across northern New England (decentralized governance, changing demographics, economic struggles, predominantly rural population patterns, uneven access to infrastructure) suggest that the lessons we have learned in New Hampshire would be useful to others in similar contexts. Concerns about youth, public education, substance-use disorders, housing, economic dislocation, welcoming immigrants and transportation, for example, are shared across the region. Authentic and inclusive engagement emphasizing participatory democratic practices can be one way to address these concerns.

Finally, we expect that the need for continued attention to racial, social and political equity will be at the heart of our work. Inequality in income and opportunity are likely to increase in the years ahead, fueling the polarization, fear and resentment that has grown in recent years. We believe that face-to-face conversations that are locally framed and focused on finding a pragmatic common ground will be key to creating communities that work for everyone. Civic engagement practices that reflect local values and democratic ideals will be an important part of both healing past wounds and designing more inclusive futures. The answers lie within us and our communities. We just have to ask the right questions and be willing to have the courageous conversations necessary to find our way forward.

Bruce Mallory is professor emeritus, former provost/executive vice president of UNH and co-founder of NH Listens. He is currently senior adviser to NH Listens. Quixada Moore-Vissing is project manager, Everyday Democracy and NH Listens Fellow. Michele Holt-Shannon is co-founder and director of NH Listens.