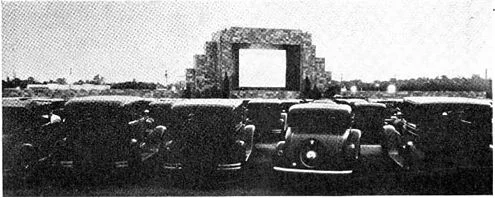

It was a sunny fall day, and we were stretched out on the grass of Dexter Park in Providence. Behind us loomed the crenellated towers of the ginormous Cranston Street Armory, a castle-like structure of ochre brick.

“He was a tea dancer,” I said to Linda.

“What the hell’s that?” she asked, a smile breaking across her face.

“Rich ladies would have teas in their homes, and he would go dance the tango with them.”

“Are you making this up?”

“No. He was, reputedly, a gigolo before he became Rudolph Valentino, and he danced for money and sometimes even for free.”

“And he danced there?” asked Linda, gesturing with her thumb to the Armory.

“Yes. That’s a fact. He would travel and give tango exhibitions, and he came to Rhode Island once and performed right there, at the Cranston Street Armory.”

“Can we go get some lunch? I’m starving,” said Linda.

“Sure. And I’ll tell you another story about the Cranston Street Armory.”

Sitting at a restaurant table outside, I reached across and took one of Linda’s hands in mine.

“Isn’t it funny that we can hold hands like this, but if you were my girlfriend, people would look at us?” said Linda.

“Do you really think they would?”

“Are you kidding? They would give us dirty looks. I wish I was a man. Six feet tall, at least, and two hundred pounds.”

“Good Lord, why?”

“So I could smash people in the face who make me angry.”

“I don’t make you angry, do I?” I asked.

“Not usually. Do you like holding my hand?”

“I love holding your hand.”

“My girlfriend would kill me if she saw us doing this.”

“You have beautiful hands, Linda.”

“Why don’t you tell me the other story about the Cranston Street Armory?”

“OK. When I was a kid, my father and I drove to Providence to see the Rhode Island Auto Show, which was held in the Cranston Street Armory. As soon as we walked in the door, the cigarette smoke was so thick both of my nostrils started bleeding.”

“They allowed smoking?”

“Linda, when I was a kid, people smoked everywhere. People smoked in hospitals and doctors’ offices. My parents didn’t smoke, so I wasn’t used to being around it. Plus, I was prone to nosebleeds anyway. But I remember it was so acrid and sharp, then — bloosh!”

“So, did you leave?”

“Well, my father really wanted to see the show, so he took me out to the car and I lay down in the back seat while he went back in.”

A month later, Linda told me that she and her girlfriend were moving to San Francisco.

“It’s supposed to be friendlier,” she said.

“You mean for gays?”

“Yeah. And for lesbians, too.”

“You mean you’re a lesbian?” I asked her.

“Ha-ha,” she replied.

“Maybe you’re not. Sometimes I get that feeling.”

“You’re just wishing I wasn’t. For you.”

“It’s true. So what?”

“You know, when you told me that Rudolph Valentino danced at the Cranston Street Armory, I didn’t know who you were talking about. I had to research him.”

“You’re kidding!”

“C’mon. You’re old enough to be my father.”

“So what? Valentino died in—”

“1926.”

“That’s decades before I was born. He’s part of American history. If I knew of him, you certainly should have.”

“Well, I didn’t. I should get going,” said Linda, and she kissed me on the cheek.

“I love you,” I said.

“I know,” she replied.

Two years later, I was weed rousting when an unfamiliar sedan pulled up to the curb. Linda stepped out. She wore jeans and a light brown zippered jacket. Her hair had grown to her shoulders with a natural wave.

We sat in my side yard and drank iced tea that still left my mouth parched.

“So,” ventured Linda with great effort and after a deep sigh, “do you have a girlfriend?”

“I do,” I replied, feeling my face grow hot.

“I thought you would,” said Linda, to which I replied, “I assume you and what’s-her-name are still together?”

“Uh-huh,” said Linda, and then she looked down.

It was like living life through stained glass. Every word now was carrying more weight than could be borne. It was impossible to go on. Linda stood up. From a jacket pocket she withdrew an old postcard protected in a plastic sleeve.

“I saw this at a flea market and thought of you. Here—” and she handed it to me.

It was a colorized photograph of the Cranston Street Armory. Beneath the photograph was printed, “New Armory.” I turned it over. On the backside the postmark, 1923, was still clearly visible, and there was a penciled message. In an elegant, cursive hand the message read: “Thanks for the dance. (signed) Rudolph Valentino.”

When I looked up, Linda was already heading back to her car.

Charles Pinning is the author of the Rhode Island-based novel “Irreplaceable”.