From The New England Journal of Higher Education (NEJHE), a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

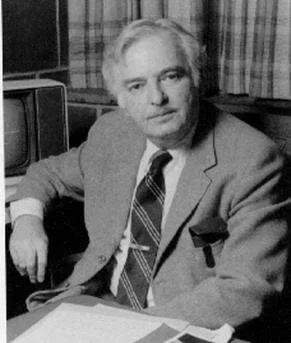

Stephen J. Nelson is professor of educational leadership at Bridgewater State University and Senior Scholar with the Leadership Alliance at Brown University. In the following Q&A, NEJHE Executive Editor John O. Harney asks Nelson what lessons today’s leaders could learn from his latest book, John G. Kemeny and Dartmouth College: The Man, the Times, and the College Presidency (Lexington Books, September 2019).

Harney: Your new book explores the life of Dartmouth College President John Kemeny. Why is Kemeny’s story particularly relevant today?

Nelson: John Kemeny was inaugurated as president of Dartmouth on March 1, 1970, two months almost to the day before the killings at Kent State. To say that the times were tumultuous both inside the gates of Dartmouth and outside is an understatement for sure. How different were those times from ours today? We don’t need to go through the entire litany of major issues and upsets in the contemporary era: terrorism foreign and domestic; economic crashes and rebounds; and political polarization and ideological loggerheads to suggest that current times are not a hallmark of stability. How Kemeny handled his times as the leader of a college ranging from the strains of internal and external political and ideological battles to fiscal stability in unstable economic cycles informs well and fully how and what college presidents today should do.

One important feature of Kemeny’s story that stands out today is that he was a man who came to America as a Hungarian immigrant, his family in 1940, fleeing the onslaught of Hitler’s horrors. When Kemeny arrived in New York City, he knew virtually no English, learning it on the fly as a 14-year-old high school sophomore as George Washington High, one of the elite city schools in the 1940s. Then just two years later, he graduated as valedictorian. He went directly to Princeton University, double majoring in math and philosophy.

During his third year there, he left the undergraduate life for one year, joining the Army. He was not yet a U.S. citizen, which he had to become rapidly because he was quickly assigned as a new private just through basic training in January 1945 to Los Alamos and the Manhattan Project working in the final stages of the development of the atom bomb. He returned to Princeton, graduated in four years from matriculation and staying on for his Ph.D. in math and serving as a research assistant to Albert Einstein.

His faculty leadership at Dartmouth is unparalleled—building a math department, co-inventing BASIC, the very influential computer language, and pioneering college computing through the Dartmouth Time Sharing System (DTSS) and then on to the college’s presidency. He came to our shores as a stranger, fully embraced being an American and had an enormous impact on education and the life and affairs of the colleges and our nation. Those contributions as citizen, educator and leader included toward the end of his presidency chairing the Three Mile Island Commission.

It is trite to call his life the fulfillment of the American Dream, but it was that and more, and his footprint remains large and lasting today. And in the current environment, might a family like the Kemenys and a contributing citizen like John be prevented entry to our country? We could hope not, but there would be no guarantee. Taking “your tired, your poor, your huddled masses” was the right thing then and should still be considered the right thing today.

Harney: What were some of the key challenges of the time?

Nelson: John Kemeny’s and Dartmouth’s challenges were many. The country was torn asunder by a debatable and highly contested war. There were continuous strains and pressures of protests to insure full citizenship and equity to Black Americans as well as other minorities, including women. The nation, with enormous impact on the budgets and financial stability of colleges and universities, faced three major recessions one of which in 1973-74 was by some measures as disastrous as the Great Recession of 2008. The reality became clear that the post-World War II through part of the 1960s public funding of colleges and universities was not going to be sustained. And that led quickly to massive belt-tightening brought about by enormous cutbacks (not stanched in the decades since) in federal funding of higher education.

Finally, the drumbeat of the leftover political animus and polarization begun in the 1960s continued to build through the 1970s to what came to be known as political correctness and the ideological battleground that has persisted now for five decades since.

Harney: You have a chapter on “Navigating Affairs Inside the Gates: The Horrors of “Animal House, ” the Indian Symbol, and the right-wing Dartmouth Review.” How did Kemeny’s tenure change Dartmouth’s place in the higher education landscape?

Nelson: Dartmouth in the 1970s had much of the best of worlds mixed with the worst of worlds. Overall, Kemeny’s presidency placed a highly positive imprint on the Dartmouth of those days and its future. He navigated the most difficult decision in Dartmouth’s then 200-year history when he moved—really educated—the campus, the alumni body and the trustees in the successful transition to coeducation. Not only did the college admit women for the first time in a previously all-male history, but doing it did so in a way that within a few short years found women students fully participating (certainly notwithstanding push back from disgruntled alumni in the early years) in the academic, athletic and social life of the campus.

That decision alone raised Dartmouth’s profile as a major player among the elite colleges of the day, some of whom also recently had become coeducational and others that had women in their student bodies for many years. Kemeny knew and argued publicly that if the college had shirked and shrunk from co-education, it would have decided tragically to consign itself to second-class status for the next chapters in its history. He was determined that could and would never be Dartmouth’s fate.

The Dartmouth Review was a thorn in Kemeny’s side in his last year in office (the paper distributed its inaugural issue at his penultimate commencement as president in 1980). Kemeny fought the paper even if in the short time he had remaining in office, he was not able to duke things out with them as he might have been able to do had he had longer. However, in the face of their charges and complaints about diversity, a changing Dartmouth and a litany of other allegations, Kemeny was able to maintain his and the college’s focus on equity in continuing to diversify its student body, faculty and administrative ranks and to keep Dartmouth on an even keel even as the institution evolved so significantly in the short space of the decade of the 1970s. And the gathering strength of the college that he set in motion created the stage that James Freedman as president in 1987 was able to stand on as he pricked the balloon of the Review once and for all, leaving them with vastly diminished credibility and stature. Without the platform that Kemeny had put in place, Freedman would not have had the leverage he was able to utilize to face down the Review (over their “Ein Reich, Ein Volk, Ein Freedman” front page banner) in his first months in office.

Harney: You also have a chapter on the “Economic Shocks of the 1970s.” Do you think presidents today are prepared for an overdue economic slowdown?

Nelson: One of Kemeny’s great genius creations and something initiated at Dartmouth and modeled by almost every college and university since, was the change he made in how endowment income should be conceived and utilized. He knew that having annual college budgets sway with the good or bad fortunes of the market, and investment income and portfolio performance was unnecessarily unstable and unsustainable.

Mathematician that he was, though it was not rocket science, he figured out the calculus of how to get around those undulations. It was simply to establish a conservative, he thought about 5 percent annually, using an average drawdown calculated on a five-year basis for endowment income. Thus in a good year of market performance, the positive difference would be plowed back into the endowment. That then created a rainy day fund for those years when the market fell below five-year average such that the annual operating budget built for the roughly five percent would be able to run without a deficit.

Today, most colleges and universities have partial preparation and security in the face of economic slowdowns if they, as most do, handle their portfolios and the use if their endowment incomes in this way.

The second thing he initiated on the fiscal affairs front at Dartmouth that has now also been mimicked by many, maybe most colleges and universities, was that when building a new building or even undertaking a large renovation of an existing one, that the total budget for the project had to include maintenance and depreciation. That is, it is going to cost money, real money to keep any building running and maintained: heat, light, custodial coverage, roof, plumbing and maybe even a next major renovation.

That continuing, unrelenting and unforgiving cost had to be planned for as a way of overcoming the oxymoronic idea of “deferred maintenance.” That brought further annual stability to Dartmouth’s budgets and plant operations. While that alone doesn’t solve every part of ensuing economic challenges, it is a further hedge against having any one or two annual budgets be overly struck and stymied by national and global economic cycles and even major downturns.