From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

There has been a growing consensus among authorities, especially in the Trump era, that the U.S. is in an epistemological crisis that threatens our democracy.

Former President Obama, for example, in a recent Atlantic interview, said: “If we do not have the capacity to distinguish what’s true from what’s false, then by definition the marketplace of ideas doesn’t work. And by definition, our democracy doesn’t work. We are entering into an epistemological crisis.”

If this is true, it is an issue which the academic and journalistic communities—i.e. those in charge of the public’s knowledge and education nationwide—need to address.

There are plenty of indications that Obama was right. The 2020 election intensified this awareness. David Brooks, in his New York Times column of Nov. 27, wrote that “77 percent of Trump backers said Joe Biden had won the presidential election because of fraud. Many of these same people think climate change is not real. Many of these same people believe they don’t need to listen to scientific experts on how to prevent the spread of the coronavirus. We live in a country in epistemological crisis, in which much of the Republican Party has become detached from reality.”

On that same day, Michael Gordon, in an op-ed for The Washington Post, wrote: “Journalism is important, and there should be more of it. An informed electorate, in the long run, will have better democratic outcomes. But the urgent problem of American politics is not an insufficient airing of policy disagreements; it is that policy views have become a function of cultural identity. A matter such as climate disruption, for example, attracts comparatively little informed and reasoned disagreement. Climate skepticism has become a tenet of populism—a revolt against elitist scientists and liberal politicians seeking excuses for social and economic control. The denial of climate change has become a cultural signifier, the policy equivalent of a gun rack in a truck.”

Multidimensional crisis

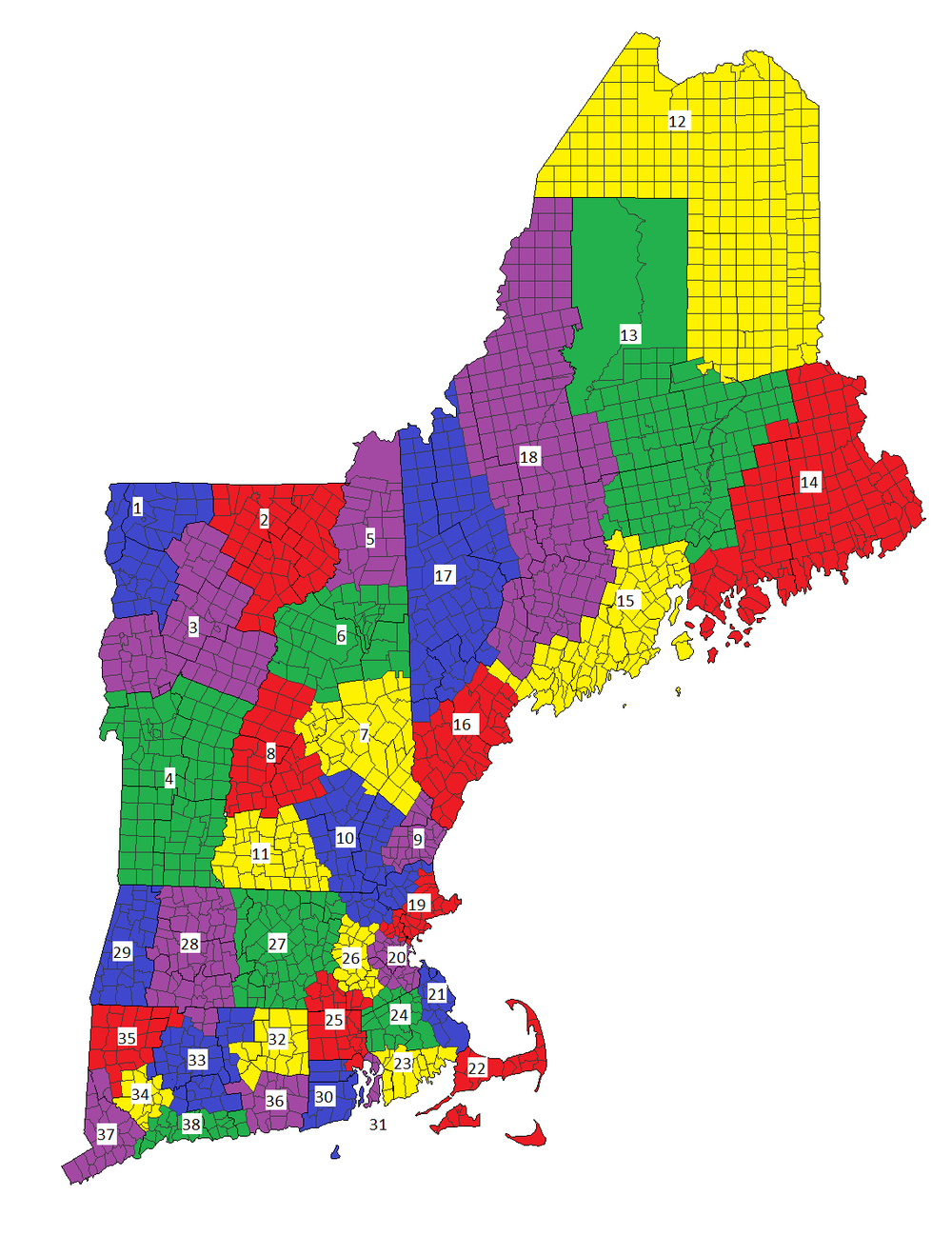

The crisis has several dimensions beyond the intellectual one. Robin Givhan, in her Washington Post column on Feb. 17, 2021, reported: “Surveys have shown that political polarization along educational lines has deepened. The gap between college-educated voters and non-college-educated voters has grown steadily over the past 60 years. The 2020 presidential election hinged on the diploma divide, which in turn, contributes to differences in income, household wealth, jobs, place of residence, cultural values and access to opportunity. … For the past four decades, incomes rose for college degree holders even as they fell for those without one, generating frustration, resentment and anger. With nearly three-quarters of new jobs requiring a bachelor’s degree, excluding nearly two-thirds of adults, earnings are linked to learning in ways that weren’t true during the 1950s and 1960s.”

There is also a technological dimension. Whereas it used to be thought that the internet would enhance democracy, we have seen an opposite effect. Thomas Edsall, in The New York Times, also on Feb. 17, wrote that “a decade ago, the consensus was that the digital revolution would give effective voice to millions of previously unheard citizens. Now, in the aftermath of the Trump presidency, the consensus has shifted to anxiety that such online behemoths as Twitter, Google, YouTube, Instagram and Facebook have created a crisis of knowledge—confounding what is true and what is untrue—eroding the foundations of democracy.”

Nathaniel Persily, a Stanford University law professor, summarized the dilemma in his 2019 report, “The Internet’s Challenge to Democracy: Framing the Problem and Assessing Reforms.” He wrote that “in a matter of just a few years the widely shared utopian vision of the nternet’s impact on governance has turned decidedly pessimistic. The original promise of digital technologies was unapologetically democratic: empowering the voiceless, breaking down borders to build cross-national communities, and eliminating elite referees who restricted political discourse. Since then that promise has been replaced by concern that the most democratic features of the internet are, in fact, endangering democracy itself. Democracies pay a price for Internet freedom, under this view, in the form of disinformation, hate speech, incitement and foreign interference in elections.”

He continued, “Margaret Roberts, a University of California-San Diego political scientist, says bluntly, ‘The difficult part about social media is that the freedom of information online can be weaponized to undermine democracy.'” In an email to Edsall, she wrote, “Social media isn’t inherently pro[-] or anti-democratic, but it gives voice and the power to organize to those who are typically excluded by more mainstream media. In some cases, these voices can be liberalizing, in others illiberal.” We are reminded that while Franklin Roosevelt used radio for fireside chats to promote his liberal agenda, Hitler was using it to promote his fascism.

Today, the new technology is more dangerous, because with AI, it becomes progressively easier to disguise mis- or disinformation as authentic news, and to scrape data from users’ devices to then target the citizens most likely to be vulnerable to dissuasion. Training in “media literacy” or how to discern authentic from fraudulent communication especially on the web, has been a growing field for decades, and will continue to be so as technology advances. But communications techniques and evaluation of sources are less our concern here than epistemology per se, and, in particular, reliance upon trusted sources, which most people use as their criterion for recognizing truth.

The truth is out there?

What is to be done? First, let us understand that the principal constituency bearing civic responsibility for the health and welfare of public intelligence, has to be scholars and educators, including journalists; and that in these roles, our professional and technical focus must be less on the economic, technological or even psychological and moral dimensions of the epistemic (i.e. relating to knowledge) crisis than on its epistemological (i.e. the study or science of knowledge) core.

We notice that the journalistic discussions quoted above focus on trust as the main issue—i.e., whom people should or want to believe in matters of science, public policy or politics and how trustworthiness has been subverted by political, economic and technological developments. While it is probably true that this is how most people actually know and think, as scholars we do not and, in fact, are trained not to trust even one another, because trust is an invalid and unreliable criterion of truth. From our professional perspective, public trust itself is intrinsic to the public’s epistemological crisis.

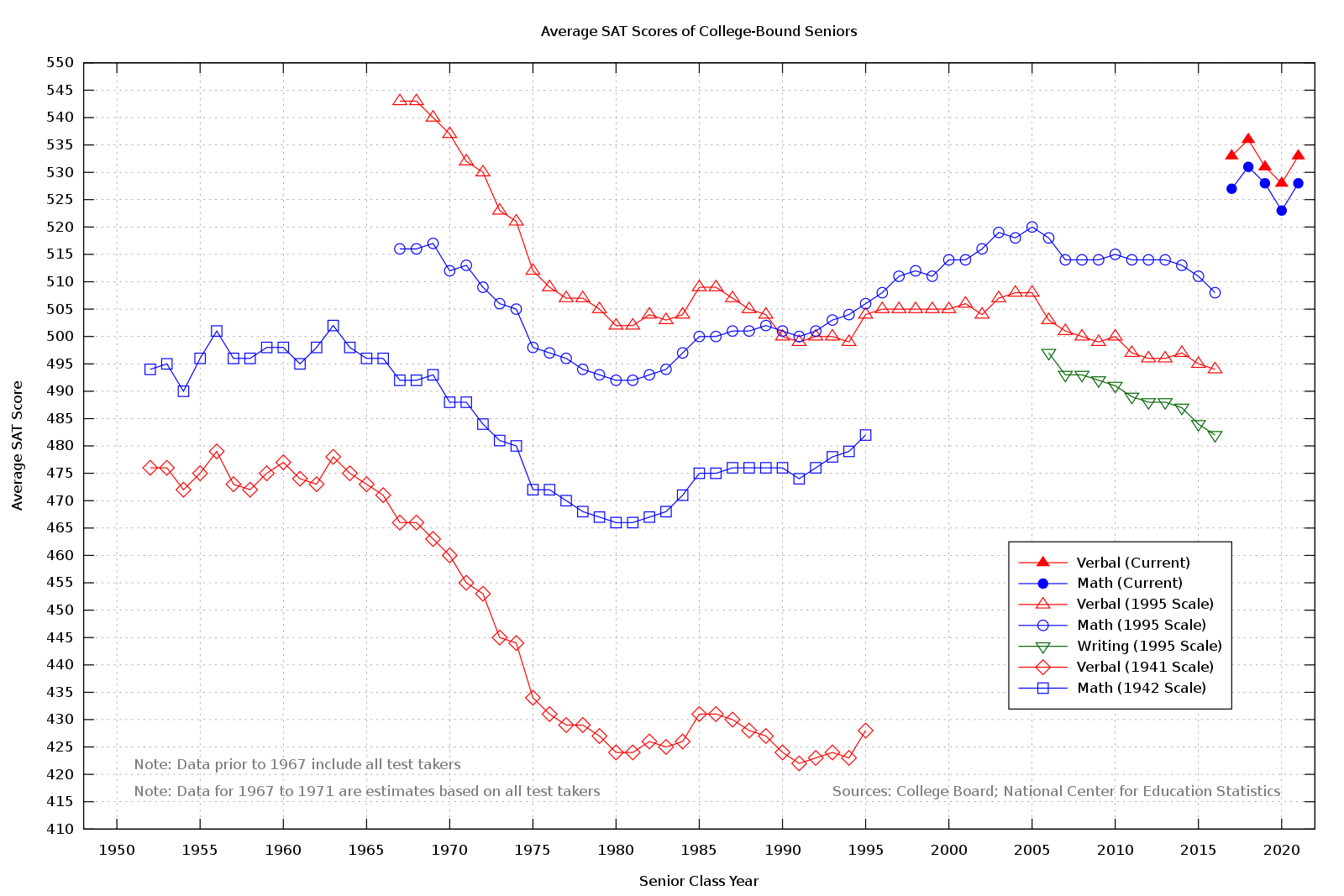

Another intrinsic element of that core obviously is inadequate factual knowledge or sheer ignorance of how and why our government works. On our watch over the past 50 years, there has been a steady erosion in the teaching of civics and history. While we spend about $50 per student annually on science and math education, only about five cents is allocated to civics education. Ten states currently have no civics requirement in schools. Large numbers of Americans cannot even name the three branches of government, never mind the value for democracy of checks and balances, or how elections are essential for peaceful transfers of power. This past year we have seen how misunderstanding of governmental politics has fed distrust, non-participation and polarization. The federal government is aware of this and has developed a purportedly high-quality K-12 civics and history program called “Educating for American Democracy,” but it has not been funded for implementation. While this initiative might help to address the knowledge issue,it does not address the crisis in epistemology—confusion about how to know and recognize truth.

Many years ago, on my first day at Brown University, the freshman class assembled in Sayles Hall to be welcomed by the university’s president, Barnaby Keeney (later the founding director of the National Endowment for the Humanities). He told us that one of the most essential and valuable skills we would learn in college—central to every scholarly discipline as the most reliable way to think about the world—was “to think on the basis of evidence.” That simple phrase—this was the first time I had heard it—blew me away, and has stuck with me for life.

Several years later, while studying history in graduate school at Columbia University, I recall discussions we often had with fellow students in one of the nation’s leading schools of journalism. They were being taught to build their stories around “balance” among various contending points of view, as a “fair” way to report to the public on current events. We history students considered this absurd, ridiculous and misleading to the public, implying that all points of view are equally valid and significant. We were right, but we see today that “balance” has set the modern standard in journalism, still practiced and still, as predicted, pernicious and dangerous. I have been amazed at how leading journalists these days struggle to articulate the challenge of ascertaining truth, treating it as discovering whom to trust. They rarely use the word “evidence”—a rare exception is Lester Holt of NBC Nightly News, who said recently in accepting the Edward R. Murrow Award for Lifetime Achievement in Journalism, “I think it’s become clearer that fairness is overrated,” and he advocated that reporters not give “unsupported arguments” equal coverage.

Follow the evidence

About the only venue where “evidence” has been determinative in current politics is our court system, wherein attempts by Trumpists to quash results of the last presidential election on grounds of corruption were summarily rejected by 63 courts at all levels nationwide for their total “lack of evidence.” The words were quoted by reporters of those decisions, and gradually the criterion of “evidence” has begun to be used comfortably by leading journalists, though we do not know if they appreciate its epistemological value—in fact, necessity in determining truth.

But the health of our democracy cannot safely rely solely on our judiciary and the best of journalism, which brings us back to the issue of our proper civic responsibilities, as scholars and teachers, for the health of public thought and discourse. What can we do to help resolve our national epistemological crisis, to protect our democracy?

First, we need to promote, for all courses and disciplines in all colleges and universities, explicitly and emphatically, that the best—i.e., surely, most reliable—way to think about the world is “on the basis of evidence.” We must work to help make it consciously automatic and habitual for all who are in or have been to college.

Second, and this is critically important, there is no reason “thinking on the basis of evidence” cannot also be taught as the explicit standard and simple lesson throughout secondary schools nationwide. We need to promote this pedagogy in every way we can, including in the media, to eliminate the apparent political divide between citizens who have been to college and those who have not. There is no justification for this particular separation in our body politic.

Third, we need to promote at every opportunity stronger academic, journalistic and media offerings in American history and civics, to combat the widespread ignorance that has also undermined our politics.

Fourth and finally, we need to promote to journalists their need to habitually ask, as the first question after hearing any political opinion or unsupported assertion, “What’s your evidence?”, and if none is forthcoming, to report that fact—that non-event as an event, that the dog didn’t bark, as it were—an integral part of their stories. This past year, it took far too long for that to happen with countless baseless assertions about the election. Journalism is a teaching profession; its responsibility is to provide the first or early accounts of current history for public use and information. Journalistic “fairness” should be to truth in public record, not to all sides of contentions in controversies.

We cannot and do not expect epistemological problems, much less crises, to be successfully resolved for all parties in any specific time frame. All I am advocating here is a concerted effort on the part of as many of us as possible to achieve a better—more constructive—balance in public discourse, between efforts to promote respect for truth, and efforts to promote partisanship with no respect for truth. I have attempted to identify the main parties responsible for truth in civic and political packaging—i.e., scholars, educators and journalists—who are all our public’s teachers. These responsible parties must work much harder to promote “thinking on the basis of evidence” rather than trusting people or institutions as a way of learning truth, on which the health of our democracy necessarily depends.

George McCully, a historian, has been a former professor and faculty dean at higher- education institutions in the Northeast, then professional philanthropist and founder and CEO of the Catalogue for Philanthropy.