David Warsh: What went wrong in Epidemiologists’ War

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

It is clear now that United States has let the coronavirus get away to a far greater extent than any other industrial democracy. There are many different stories about what other countries did right. What did the U.S. do wrong?

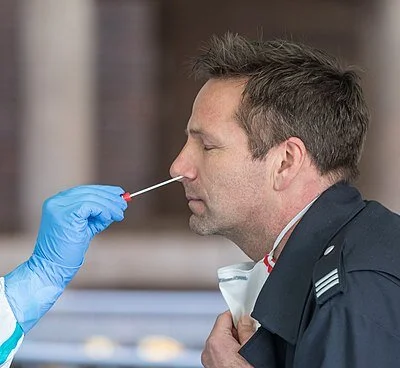

When the worst of it is finally over, it will be worth looking into the simplest technology of all, the wearing of masks.

What might have been different if, from the very beginning, public health officials had emphasized physical distancing rather than social distancing, and, especially, the wearing of masks indoors, everywhere and always?

Even today, remarkably little research is done into where and how transmission of the COVID-19 virus actually occurs – at least to judge from newspaper reports. Typical was a lengthy and thorough account last week by David Leonhardt, of The New York Times, and several other staffers.

Acknowledging that previous success at containing viruses has led to a measure of overconfidence that a serious global pandemic was unlikely, Leonhardt supposed that an initial surge may have been unavoidable. What came next he divided into four kinds of failures: travel policies that fell short; a “double testing failure”; a “double mask failure”; and, of course, a failure of leadership.

The American test, developed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which worked by amplifying the virus’s genetic material, required more than a month longer to be declared effective, compared to a less elaborate version developed in Germany. The U.S. test was relatively expensive, and often slow to process. The virus spread faster than tests were available to screen for it.

As for masks, Leonhardt reported, experts couldn’t agree on their merits for the first few months of the pandemic. Manufactured masks were said to be scarce in March and April. Their benefits were said to be modest.

From the outset it was understood that most transmission depended on talking, coughing, sneezing, singing, and cheering. Evidence gradually accumulated that the virus could be transmitted by droplets that hung in the air in closed spaces – in restaurants, and bars, for example, on cruise ships, or in raucous crowds. By May, it became more common for official to urge the wearing of masks.

But Leonhardt cited no evidence of the rate at which outdoor transmission occurred among pedestrians, runners or participants in non-contact sports. Nor did he take account of wide disparities of distance across America among people in cities, suburbs, and country towns. In many areas, most people used common sense, which turned out to be pretty much the same as medical advice.

Instead of becoming ubiquitous indoors and out, as in Asia, or matters of fashion, as in Europe, Leonhardt wrote, masks in the United States became political symbols, “another partisan divide in a highly polarized country,” unwittingly exhibiting the divide himself.

Whether things would have turned out differently had face-coverings been confidently mandated everywhere indoors from the very beginning, and recommended wherever where crowds were unavoidable, is a matter for further research and debate. Not much is known yet about the efficacy of various forms of “lock-down” – office buildings, public-transit, schools, college dormitories.

This much, however, is already clear: very little effort has been spent on discovering what was genuinely dangerous and what was not; still less on communicating to citizens what has been learned. Epidemiologists live to forecast. Economists conduct experiments. Expect the “light touch” policies of the Swedish government to attract increasing attention.

About the failure of leadership in the U.S., Leonhardt is unremitting: in no other high-income country have messages from political leaders been “so mixed and confusing.” Decisive leadership from the White House might have made a decisive difference, but the day after the first American case was diagnosed, President Trump told reporters, “We have it under control.” Since then consensus has only grown more elusive, at least until recently.

Word War I was sometimes called the Chemists’ War, because of the industrially manufactured poison gas employed by both sides, The German General Staff looked after their war production. World War II was the Physicists’ War,” thanks to the advent of radar and, in the end, the atomic bomb. It was equally said to be the Economists’ War, chiefly because of the contribution of the newly developed U.S. National Income and Product Accounts to war materiel planning.

The Covid-19 pandemic has been the Epidemiologists’ War. Next time look for economists to make more of a contribution. And hope for a more prescient and decisive president.

. xxx

The New York Times reported last week it had added 669,000 net new digital subscriptions in the second quarter, bringing total print and digital subscriptions to 6.5 million. Advertising revenues declined 44 percent. Earnings were $23.7 million, or 14 cents a share, down 6 percent from $25.2 million, or 15 cents a share, a year earlier.The news made the pending departure of chief executive Mark Thompson, 63, still more perplexing.

“We’ve proven that it’s possible to create a virtuous circle in which wholehearted investment in high-quality journalism drives deep audience engagement, which in turn drives revenue growth and further investment capacity,” Thompson said. His deputy, Meredith Kopit Levien, 49, will succeed him on Sept. 8, the company announced last month. Kopit Levien told analysts last week that the company believed the overall market for possible subscribers globally was “as large as 100 million.”

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first appeared.