David Warsh: The exciting lives of former newspapermen

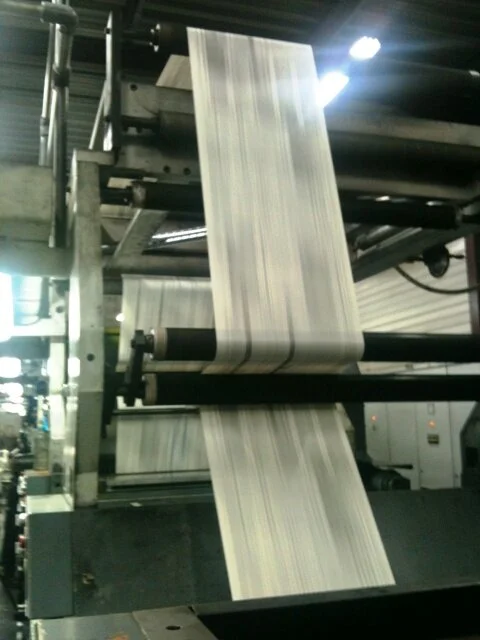

— Photo by Knowtex

SOMERVILLE, Mass.

After the Internet laid waste to old monopolies on printing presses and broadcast towers, new opportunities arose for inhabitants of newsrooms. That much I knew from personal experience. With it in mind, I have been reading Spooked: The Trump Dossier, Black Cube, and the Rise of Private Spies (Harper, 2021), by Barry Meier, a former reporter for The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal. Meier also wrote Pain Killer: A “Wonder” Drug’s Story of Addiction and Death (Rodale, 2003), the first book to dig in to the story of the Sackler family, before Empire of Pain: The Secret History of the Sackler Dynasty (Doubleday, 2021), by New Yorker writer Patrick Radden Keefe, eclipsed it earlier this year. In other words, Meier knows his way around. So does Lincoln Millstein, proprietor of The Quietside Journal, a hyperlocal Web site covering three small towns on the southwest side of Mt. Desert Island, in Downeast Maine.

Meier’s book is essentially a story about Glenn Simpson, a colorful star investigative reporter for the WSJ who quit in 2009 to establish Fusion GPS, a private investigative firm for hire. It was Fusion GPS that, while working first for Republican candidates in early 2016, then for Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign, hired former MI6 agent Christopher Steele to investigate Donald Trump’s activities in Russia.

Meier, a careful reporter and vivid writer, doesn’t think much of Simpson, still less of Steele, but I found the book frustrating: there were too many stories about bad behavior in the far-flung private intelligence industry, too loosely stitched together, to make possible a satisfying conclusion about the circumstances in which the Steele dossier surfaced, other than information, proven or not, once assembled and packaged, wants to be free. William Cohan’s NYT review of Spooked was helpful: “[W]e are left, in the end, with a gun that doesn’t really go off.”

Meier did include in his book (and repeat in a NYT op-ed) a telling vignette about Fusion GPS co-founder Peter Fritsch, another former WSJ staffer who in his 15-year career at the paper had served as bureau chief in several cities around the world. At one point, Fritsch phones WSJ reporter John Carreyrou, ostensibly seeking guidance on the reputation of a whistleblower at a medical firm – without revealing that Fusion GPS had begun working for Elizabeth Holmes, of whose blood-testing start-up, Theranos, Carreyrou had begun an investigation.

Fritsch’s further efforts to undermine Carreyrou’s investigation failed. Simpson and Fritch tell their story of the Steele dossier in Crime in Progress (2019, Random House.) I’d like to someday read more personal accounts of their experiences in the private spy trade, I thought, as I put Spooked and Crime in Progress back on the shelf Given the authors’ new occupations, it doesn’t seem likely those accounts will be written.

By then, Meier’s story had got me thinking about Carreyrou himself. His brilliant reporting for the WSJ, and his 2018 best-seller, Bad Blood: Secrets and Lies in a Silicon Valley Startup (Knopf, 2018, led to Elizabeth Holmes’s trial on criminal charges that began last month in San Jose. Thanks to Twitter, I found, within an hour of its appearance, this interview with Carreyrou, now covering the trial online as an independent journalist.

My head spun at the thought of the leg-push and tradecraft required to practice journalism at these high altitudes. The changes wrought by the advent of the Web and social media have fundamentally expanded the business beyond the days when newspapers and broadcast news were the primary producers of news. In 1972, when I went to work for the WSJ, for example, the entire paper ordinarily contained only four bylines a day.

So I turned with some relief to The Quietside Journal, the Web site where retired Hearst executive Lincoln Millstein covers events in three small towns on Mt. Desert Island, Maine, for some 17,000 weekly readers. In an illuminating story about his enterprise, Millstein told Rick Edmonds, of the Poynter Institute, that he works six days a week, again employing pretty much the same skills he acquired when he covered Middletown, Conn., for The Hartford Courant forty years ago. (Millstein put the Economic Principals column in business in 1984, not long after he arrived as deputy business editor at The Boston Globe).

My case is different. Like many newspaper journalists in the 1980s, I worked four or five days a week at my day job and spent vacations and weekends writing books. I quit the day job in 2002, but kept the column and finished the book. (It was published in 2006 as Knowledge and the Wealth of Nations: A Story of Economic Discovery).

Economic Principals subscribers have kept the office open ever since; I gradually found another book to write; and so it has worked out pretty well. The ratio of time spent is reversed: four days a week for the book, two days for the column, producing, as best I can judge, something worth reading on Sunday morning. Eight paragraphs, sometimes more, occasionally fewer: It’s a living, an opportunity to keep after the story, still, as we used to say, the sport of kings.

David Warsh, a veteran columnist and an economic historian, is proprietor of Somerville-based economicprincipals.com, where this essay first ran.