Scup popular, but not so much where a lot of it comes from -- R.I.

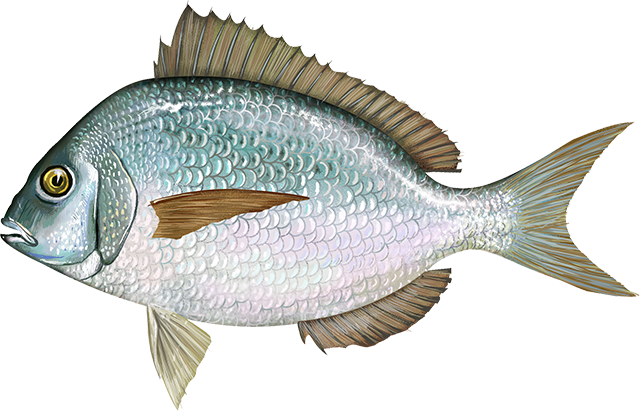

Scup

Consider the humble scup.

Ignored, disrespected, even feared, scup is one of the most plentiful fish in Narragansett Bay, a climate-change winner whose numbers are rising with Rhode Island’s water temperatures. Yet many Rhode Islanders have never heard of it, let alone tasted one.

Rhode Island fishermen caught more than 4 million pounds of scup in 2021, making it the state’s biggest catch among fish and second in the state’s commercial seafood school only to that better-known kingpin — squid, aka calamari.

While calamari is Rhode Island’s popular state appetizer, you won’t find scup in most supermarket seafood cases in the Ocean State. Instead, most of the commercial catch is exported to large cities like New York, Philadelphia, and Chicago with large immigrant populations whose cultures are more familiar with scup.

To read the article, please hit this link.

Eat oysters to fight global warming

“Still-Life with Oysters,’’ by Alexander Adriaenssen

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

Eating oysters is good for the environment, according to a pair of Narragansett Bay-centric experts. Scientists Robinson Fulweiler, of Boston University, and Christopher Kincaid, from the University of Rhode Island’s Graduate School of Oceanography, shared their latest findings during a webinar last fall.

Fulweiler studies the impact that wild and aquaculture oysters have on their surrounding waters. A single oyster can filter up to 50 gallons of water daily. Their most important service, and the one Fulweiler studies most, is removing nitrogen from marine waters that could trigger algal blooms.

“Aquaculture, as well as restored oyster reefs, have high rates of nitrogen removal,” Fulweiler said.

Excessive nitrogen in waters such as Narragansett Bay is dangerous for aquatic habitats and marine life, as it can feed toxic blooms. These events are also linked to low levels of oxygen in the water, which can lead to fish kills like the one in Greenwich Bay in 2003 that killed tens of thousands of fish.

Oysters, including those in aquaculture operations, help out by removing nitrogen and other pollutants from stressed waters. Instead of being biologically available to feed algae growth, the chemical used in fertilizers is released into the atmosphere as nitrous oxide. Aquaculture and restored reefs have a strong impact on denitrification, according to Fulweiler.

“Oyster aquaculture and oyster reefs are behaving similarly in terms of the nitrogen removal process,” she said.

The two biggest greenhouse gases that oysters emit are nitrous oxide and carbon dioxide, and while they are powerful climate emissions, the amounts that oysters release as part of denitrification are negligible. In fact, Fulweiler sees moving toward protein sources from aquaculture as key to reducing emissions generated by land-based farming.

“The take-home message is if you eat a whole bunch of oysters, the amount of nitrous oxide released into the environment is negligible compared to [if you ate] chicken, pigs, sheep or cows,” Fulweiler said.

Kincaid has spent the past 20 years tracking the movements of water and nitrogen in Narragansett Bay. A self-described “coastal plumber,” he is building a predictive computer model to use in the state’s coastal waters. Kincaid cited a 2003 fish kill as a prime reason to examine water quality, nutrient dynamics, and algal blooms.

Low oxygenated areas in the coves, harbors and estuarine waters of Narragansett Bay have “amazingly stable” gyres, or vortexes, that move currents slowly in a clockwise direction. Kincaid and his team use Regional Ocean Modeling Systems to track these currents after accounting for tidal flows.

“We could use [this data] around aquaculture farms and predict how water flows in and out,” he said.

Nitrogen enters Narragansett Bay from the north and south. In the north, much of it comes from wastewater-treatment plants. In the south, it comes in through massive water intrusions from Rhode Island Sound, traveling through the East Passage — the channel of water between Jamestown and Aquidneck Island.

“The amount of water coming in on these intrusions is on average twice the same amount that goes over Niagara Falls every day,” Kincaid said.

The professor of oceanography said he and his research team aren’t entirely sure what else is in some of these East Passage water intrusions besides high levels of nitrogen, but has a future study planned to investigate.

Aquaculture and waterfowl

URI graduate student Tori Mezebish holds a black duck she tagged as part of her research on the interactions between waterfowl and aquaculture facilities. (Courtesy photo)

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

As aquaculture operations expand in Narragansett Bay and Rhode Island’s salt ponds, questions have arisen about how ducks and geese are impacted by the facilities. To begin to answer these questions, a University of Rhode Island doctoral student is tracking the movements of local waterfowl.

“There haven’t been any Rhode Island studies yet, but studies on the Pacific Coast have found issues with diving ducks getting tangled up in netting used by aquaculture, and birds that have been deterred from areas that might otherwise be good habitat because of the activities of aquaculture operations,” said Tori Mezebish, a native of Maryland who is collaborating on the project with URI professors Peter Paton and Scott McWilliams and officials from the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management.

She noted previous studies have also observed sea ducks such as eiders and scoters, which feed on mollusks, preying on oysters and other shellfish being grown by aquaculturists.

“There’s also been some positive associations, like ducks and geese eating some of the aquatic vegetation that accumulates on the cages,” Mezebish said. “It’s a mixed bag of how the birds might interact with aquaculture.”

Last winter, Mezebish attached transmitters to 30 black ducks and 30 brant, a species of goose that lives in salt water. This winter she will deploy an additional 30 transmitters on common goldeneyes, a diving duck. All three species are common during winter in Narragansett Bay, the state’s salt ponds, and adjacent salt marshes.

Most of the brant have returned from their breeding grounds in the Arctic, and several of them spend every day with dozens of other brant on the lawn at Colt State Park in Bristol. Others are spending most of their time in the upper bay and Providence River. The black ducks are just beginning to return to the area from Maine and southern Canada, and the early arrivals have been tracked to the salt ponds and the Galilee area.

Mezebish is tracking the movements of each bird using a GPS unit on their transmitters to see how much time they spend near aquaculture facilities. She is also observing the birds in the field to validate the GPS data and see what the birds are doing around the shellfish farms.

“The goal is to understand what is important to these species outside of the aquaculture facilities,” she said. “Maybe brant need shallow areas with submerged vegetation, so that may not be the best place to put an aquaculture lease.”

In addition to Mezebish’s study, URI postdoctoral researcher Martina Müller is conducting land-based surveys throughout the year to see what other kinds of birds may be interacting with aquaculture facilities.

“Ultimately, we want to provide recommendations about the good and not so good places for aquaculture leases to be placed,” said Mezebish, who became interested in waterfowl research as an intern at the Pawtuxet Wildlife Research Center in Maryland, where she hand-reared ducklings used in the center’s research activities.

When the project is complete, Mezebish hopes to use the study as a springboard to study related questions about other conflicts and interactions between waterfowl and humans.

Caitlin Faulds: How do users interpret warnings about coastal water quality?

Misquamicut Beach, in southern Rhode Island

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

A new study on perceptions of coastal water quality shows users may have more difficulty interpreting warning signs than previously thought.

The University of Rhode Island study, recently published in the Marine Pollution Bulletin, surveyed more than 600 recreational users around Narragansett Bay regarding their understanding of water quality to find that water quality had “multiple meanings.” A complicated conceptualization of water quality could have big implications for water policy and management.

“Water quality is pretty complex for people,” said Tracey Dalton, a URI marine affairs professor and Rhode Island Sea Grant director, who co-authored the study. “It’s not as simple as the chemical components that we tend to manage for.”

Water quality managers typically look at a variety of biochemical and physical indicators, including nutrients, temperature, acidity, oxygen levels, phytoplankton, fecal coliform and enterococci, to see if a site meets surface water quality guidelines set by the Environmental Protection Agency and outlined in the Clean Water Act.

But, according to the recent study led by URI marine affairs doctoral candidate Ken Hamel, these indicators can be difficult to understand for beachgoers, who more commonly tote sunscreen and beach towels than sterile sample bottles, plankton nets or conductivity, temperature and depth (CTD) sensors.

With help from his research team, Hamel conducted hundreds of in-person surveys at 19 sites along the Rhode Island shoreline. They asked recreational users to grade water quality in the area on a scale from 1 to 10, and then explain the reasons for their score.

Users generally perceived water quality in upper Narragansett Bay to be worse than in the lower bay. This assessment aligned fairly well with biochemical reports in the area, Hamel said, generally cleaner on the southern, open end of the bay than in the more urban, post-industrial north.

“You’ve got to wonder … how do people make that judgment,” he said. “Because they don’t necessarily know how much sewage effluence is in the water. They can’t see E. coli or enterococcus. They can’t smell it. Nutrients are also invisible.”

After a statistical analysis of the responses, the survey showed nearly 23 percent of users based water quality determinations on the presence of macroalgae or seaweed.

“Seaweed, which is a perfectly ecologically healthy organism for the most part — people perceive that as a water quality problem,” Hamel said. “From a Clean Water Act perspective, [seaweed in] the north is a water quality problem, the south is not.”

In the northern reaches of Narragansett Bay, macroalgal concentrations are often the result of nutrient overload, especially nitrogen and phosphorous borne of fertilizers and road runoff. It can indicate a problem with marine water quality.

But further south, macroalgae are less associated with pollution and are not necessarily an indicator of nutrient enrichment or water degradation, according to Hamel. Seaweed grows in reefs off the coast, breaks up due to wave action and can be blown on shore, especially on south-facing sands.

With no simple association between water degradation and seaweed, Hamel was surprised to see so many people use it as a basis for water quality determinations.

“There is very little research on perceptions of algae or seaweed period,” Hamel said. “It’s just a very understudied subject.”

Shoreline trash, “broadly defined” pollution, strong odor, water clarity, swimming prohibitions and nearby sewage treatment plants were also cited by beachgoers as indicators of poor water quality.

“People figured if there was a sewage plant nearby the water must be dirty,” Hamel said. “Although if you think about it, it’s slightly backward right. That should make the water a little bit cleaner.”

Another 9 percent of respondents also indicated that firmly held place beliefs played a role in water quality grades. These place beliefs, Hamel said, were “hard to pin down,” but were based primarily on the reputation of a place, whether linked to former industry or long-embedded regional knowledge of Narragansett Bay.

“One person even said, ‘This place is too upper bay.’ Like it was just common sense for them that water in the upper bay must be bad,” Hamel said.

Narragansett Bay visitors with water-quality questions can find detailed reports for sites through the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management and through the Narragansett Bay Commission. But, according to Hamel, the survey shows a need and opportunity to better engage beachgoers in water quality education, so the average recreation user can more accurately read the warnings presented in an environment.

“As a group of social scientists, we’re really interested in understanding how people are connected to their environment,” Dalton said. “From a policy perspective, it's really important to understand what the general public thinks since they’re the ones who are going to coastal sites, they’re the ones affected by policies.”

The Clean Water Act, Hamel said, has gaps in the way it was written and interpreted by water managers. As set out in 1972, the federal law mandated that states reduce and eliminate pollutants primarily to protect wildlife and recreation. Nicknamed the “fishable/swimmable goal,” the law gives priority to recreational users.

The law is enforced at the state level, with slight variations in procedure, though it typically takes the form of measuring and monitoring biochemical and physical variables. But, according to Hamel, that strategy can leave out certain stakeholders and minimize non-user concerns.

“There’s a lot of other people that use the water that aren’t necessarily in it or on it,” he said. “And their … perspectives aren’t really considered by the way the Clean Water Act is implemented.”

There isn’t necessarily anything wrong with the law, Hamel said, and it has been instrumental in improving water quality. But policymakers and managers could better address all stakeholders and “more explicitly consider” the needs of non-users, he said, including those who may work or live nearby.

“In terms of how we direct our investments and direct our funds, we want to make sure that we’re also addressing what people care about,” Dalton said. “It’s really important to ground that in what the understanding is of the concept of water quality.”

Caitlin Faulds is an ecoRI News journalist.

Frank Carini: Warming waters are changing fish mix

From ecoRI.org

For generations, winter flounder was one of the most important fish in Rhode Island waters. Longtime recreational fisherman Rich Hittinger recalled taking his kids fishing in the 1980s, dropping anchor, letting their lines sink to the bottom, waiting about half an hour and then filling their fishing cooler with the oval-shaped, right-eyed flatfish.

Now, four decades later, once-abundant winter flounder is difficult to find. The harvesting or possession of the fish is prohibited in much of Narragansett Bay and in Point Judith and Potter ponds. Anglers must return the ones they accidentally catch to the sea.

Overfishing is easily blamed, and the industry certainly bears responsibility, as does consumer demand. But winter flounder’s local extinction isn’t simply the result of overfishing. Sure, it played a factor, but the reasons are complicated, from habitat loss, pollution and energy production — i.e., the former Brayton Point Power Station, in Somerset, Mass., pre-cooling towers, when the since-shuttered facility took in about a billion gallons of water daily from Mount Hope Bay and discharged it at more than 90 degrees Fahrenheit.

The climate crisis, however, is likely playing the biggest role, at least at the moment, by shifting currents, creating less oxygenated waters and warming southern New England’s coastal waters. These impacts, which started decades ago, have and are transforming life in the Ocean State’s marine waters. The changes also impact ecosystem functioning and services. There’s no end in sight, as the type of fish and their abundance will continue to turn over as waters warm.

Rhode Island’s warming water temperatures are causing a biomass metamorphosis that is transforming the state’s commercial and recreational fishing industries, for both better and worse. The average water temperature in Narragansett Bay has increased by about 4 degrees Fahrenheit since the 1960s, according to data kept by the University of Rhode Island’s Graduate School of Oceanography.

Locally, iconic species are disappearing (winter flounder, cod and lobsters), southerly species are appearing more frequently (spot and ocean sunfish) and more unwanted guests are arriving (jellyfish that have an appetite for fish larvae and, in the summer, lionfish, a venomous and fast-reproducing fish with a voracious appetite).

Dave Monti, a charter boat captain for the past two decades, has been fishing in Rhode Island and Massachusetts waters for 45 years. He’s seen a lot of change in a fairly limited amount of time.

He said the type of fish in Rhode Island’s marine waters today is much different than a decade ago. He pointed to the impact of a changing climate. Warm-water fish such as black sea bass, summer flounder and scup are here in abundance, according to Monti. These species are now an integral part of his charter business.

“It would have been unheard of 10 years ago to say black sea bass would be so abundant in our waters, and that it would be a big part of my charter business,” Monti said.

This transfer of fish along the Atlantic Coast is having an impact on commercial fisheries, most notably regarding the issue of assigning stock allocations.

For example, Monti noted that summer flounder moving north has created havoc with catch limits. He said Mid-Atlantic vessels, which possess the summer flounder quotas but now have fewer of the fish in their waters, have moved up the East Coast to fish. New England boats now have the fish in their waters but little allocation.

He said that the laws that govern commercial fishing need to keep up with the impacts of the climate crisis. He also noted that as warming waters change the type and abundance of fish in different regions, commercial fishermen have to retool their boats and gear and learn how to catch the species new to their waters.

Hittinger, first vice president of the Rhode Island Saltwater Anglers Association, attributes the species changes he has witnessed in local waters, at least in part, to rising water temperatures.

When the Warwick resident started fishing regularly more than four decades ago, Hittinger said he caught cod and pollack off Block Island and winter flounder in all of the state’s bays. He noted that most of these fish are largely gone, replaced by warm-water species.

Speaking as a recreational angler, Hittinger said the changing of the species found in Rhode Island’s salt waters isn’t necessarily his concern. His concern lies with regulation that is slow to change with the times. He used black sea bass as an example, noting that Rhode Island’s recreational fishing restrictions on the species, implemented by the Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management Council, were set 20 years ago. Now, he said, there are a lot more of them.

Black sea bass caught in Rhode Island waters must be at least 15 inches in length and the limit is three or seven per angler per day depending on the season. Hittinger noted that in New Jersey, where the fish is becoming slightly less plentiful, keepers must be at least 12.5-13 inches and the daily allowance is higher.

As the waters off the East Coast continue to warm, the Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management Council and the New England Fishery Management Council will likely be hearing similar concerns.

Stephen Hale, a long-time marine ecologist at the Environmental Protection Agency’s Atlantic Coastal Environmental Sciences Division Laboratory in Narragansett, said marine animals are shifting northward along the Atlantic Coast in response to the changing climate. He said the movement of a new species into an area can cause ecosystem disruption and that the depletion of key species from an area can lead to economic and social changes.

Hale noted that if your preferred habitat was warming to a level you found intolerable, you would basically have three choices: adapt (install an air conditioner, for example); move to a cooler locale (say Maine); or stay where you are and suffer the consequences (heat exhaustion, heat stroke, death).

He said many of the planet’s other species can only exercise the second option, while others are stuck with the third.

Along the East Coast numerous marine species, including bottom-dwelling invertebrates such as clams, snails, crustaceans and polychaete worms, have shifted their ranges poleward in response to rising water temperatures caused by the global climate crisis. Cold-water species such as cod, winter flounder and American lobster are moving to cooler locales.

Hale said species are trying to maintain their preferred thermal niche by moving poleward or into deeper water.

The Saunderstown resident, who retired from the EPA in 2018 after 23 years at the Narragansett lab, co-authored a 2017 study that covered two biogeographic provinces along the Atlantic Coast: Virginian, Cape Hatteras, N.C., to Cape Cod; and Carolinian, mid-Florida to Cape Hatteras.

The authors found that bottom water temperature increased 2.9 degrees Fahrenheit from 1990 to 2010. They also noted that the center of distribution of 22 out of 30 species studied shifted north in response to increasing water temperatures. Seven species shifted south, but moved just one-third the distance of the northward-movers.

“Fishermen are adaptive,” said Monti, a strong supporter of renewable energy development to address the climate crisis. “Every day is different with tides, currents, wind and bait. Warming waters and climate change are just additional factors. Regions are losing and gaining fish. It’s not going to end.

Frank Carini is editor of ecoRI.org.

Frank Carini: In two areas on R.I. coast — improvement and new challenges

The Nature Conservancy and its partners installed a living shoreline at Rose Larisa Memorial Park, in East Providence, to help keep coastal erosion at bay.

— Photo by Frank Carini/ecoRI News)

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

EAST PROVIDENCE, R.I.

Growing up in the 1970s and ’80s across the Seekonk and Providence rivers in Rhode Island’s capital, John Torgan spent plenty of time exploring the state’s urban shoreline.

He remembers them as dumps filled with sewage and littered with decaying oil tanks.

“They were horribly polluted,” said Torgan, who still lives in Providence. “No one was fishing or sailing.”

His childhood memories, however, also include the beauty of a peaceful island in the middle of a shallow 4-mile-long salt pond.

The fortunes of these waters and their surroundings have changed since an adolescent Torgan, now 51, was skipping rocks, collecting shells and investigating the coastline for marine life. The Providence and Seekonk rivers are still impaired waters, but, like the chain-link fence topped with barbed wire that once separated much of these waterways from the public, the derelict oil tanks have been removed. The rivers’ health has improved.

The two rivers, both of which share a legacy of industrial contamination and suffer from stormwater-runoff pollution, aren’t recommended for swimming, but life on, under and around them has returned. Menhaden, bluefish, river herring, eels, osprey and cormorants are now routinely spotted. The occasional seal, dolphin, bald eagle and trophy-sized striped bass visit. Kayakers, fishermen, scullers and birdwatchers are easy to find.

Torgan, who spent 18 years as Save The Bay’s baykeeper, called the comeback of upper Narragansett Bay “extraordinary” and “dramatic.” He credited the Narragansett Bay Commission’s ongoing combined sewer overflow project with making the recovery possible.

As for that summer cottage on Great Island in Point Judith Pond, he said “tremendous development” has changed the neighborhood. Bigger houses now surround the Torgan family’s saltbox cottage, adding stress to one of Rhode Island’s largest and most heavily used salt ponds.

There is a diverse mixture of development around the shores of the pond that straddles South Kingstown and Narragansett. In the urban center of Wakefield, at the head of the pond, and at the port of Galilee at its mouth, there is an abundance of commercial development and a corresponding amount of pavement. The impacts are beginning to show.

Early last year the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management decided, based on ongoing water-quality monitoring results, to reclassify two areas of Point Judith Pond from approved to conditionally approved for shellfish harvesting. Water samples collected in the pond after certain rain events showed elevated bacteria levels and resulted in several emergency and precautionary shellfishing closures.

An underappreciated coastline

As an adult, Torgan’s interest in and passion about the marine environment hasn’t waned. The avid boater and angler has spent much of his working life protecting the Ocean State’s namesake, especially the waters not typically associated with its catchy moniker.

“This is the coast,” Torgan said while standing at the water’s edge at Rose Larisa Memorial Park. “The coast of Rhode Island doesn’t start at Rocky Point. It’s not just the beaches of South County.”

But, like most of the state’s coastline, the East Providence shoreline is vulnerable to accelerated erosion driven by the climate crisis and growing development pressures. Like much of the state’s urban shoreline, the health of this stretch of beach is better but hardly pristine. It is littered with chunks of asphalt and broken glass, most of its sharp edges dulled by tumbling in the sea. Swimming isn’t advised.

The climate challenges and improved health are why the organization Torgan currently heads, the Rhode Island chapter of The Nature Conservancy, took an interest in protecting this underappreciated stretch of beach.

More frequent and intense storms, combined with increasing sea-level rise, are eroding beaches and bluffs and damaging the state’s diminishing collection of coastal wetlands. Torgan said dealing with the negative impacts of this reality, plus increased flooding, is a huge challenge for Rhode Island’s 21 coastal communities. He noted adequately supported coastal resiliency projects that use nature are needed to inoculate the state against the changes that are coming.

To that end, The Nature Conservancy partnered with the Coastal Resources Management Council (CRMC) and the City of East Providence last year to test the effectiveness of “living shoreline” erosion controls at the popular Bullocks Point Avenue park.

The park’s steep coastal bluff rises 20-30 feet above a narrow beach. In several areas, however, erosion has crumbled sections of the bluff, exposed root balls and felled trees. Previous efforts to reduce erosion through human-made practices, such as the installation of riprap and seawalls, failed.

As its name suggests, the living shoreline model incorporated more natural infrastructure. Unlike concrete or stone seawalls, living shorelines are designed to prevent erosion while also providing wildlife habitat. Hardened shorelines, compared to living ones, also diminish public access.

The first step in returning nature to a prominent role at this coastal park, at the head of Narragansett Bay’s tidal waters, was removing debris, such as large concrete slabs more than 20 feet long that were sitting at the bottom of the bluff, left behind by those failed human attempts to keep Mother Nature at bay.

Then, at the northern end of the park, the bank was cut away to reduce the slope. Stone was placed at the base of the bluff and logs made of coconut fiber were installed farther up the slope. The bluff was planted with native coastal vegetation. Near the southern boundary, low piles of purposely placed rocks and rows of beachgrass and native plants were added.

In other areas along this stretch of upper Narragansett Bay beach, boulders, cement walls and wooden structures, to varying degrees of success, strain to keep East Providence backyards from eroding and the bay from encroaching.

“As a matter of policy, we need to change our relationship with water where we’re not trying to hold it back and keep it out,” Torgan said. “In a more comprehensive way, think about how can we manage it and create basins where we are welcoming the water. That will help with flooding. It will help with sea-level rise and storm damage. It will improve water quality. The long view is changing the mindset that says we need to wall off the rising water and instead think about natural approaches and strategies that allows us to move with it.”

He noted that while living shoreline techniques have been implemented elsewhere in the United States, few have been permitted, built and evaluated in New England. He said small-scale projects like this one give coastal engineers and coastal permitting agencies a better sense of their cost and effectiveness, most notably in areas that aren’t exposed to open-ocean shoreline, like along much of the South Coast, where these artificial marshes would likely be unable to blunt stronger wave action.

When the 2020 project was announced, CRMC board chair Jennifer Cervenka said, “Much of Rhode Island’s coastline is eroding, and it’s a problem with no easy fix. This nature-based erosion control is one of the first of its kind in Rhode Island, and New England. We can’t stop erosion completely, but living shoreline infrastructure like this might buy our shores some valuable time.”

The project, which cost about $230,000, was funded by a Coastal Resilience Fund grant from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, The Nature Conservancy, the Newport-based foundation 11th Hour Racing and the Rhode Island Coastal and Estuarine Habitat Restoration Trust Fund.

Frank Carini is editor of ecoRI News.

Caitlin Faulds: Ammonia from agriculture threatens bays

— Photo by Ben Salter

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

National regulations are needed to limit harmful ammonia emissions from agricultural sources and prevent knock-on soil and water degradation in sensitive estuary ecosystems, such as Narragansett Bay, according to a study recently published in Atmospheric Environment.

The study, completed by a team at Brown University’s Institute at Brown for Environment and Society, analyzed wet-deposited ammonium, or ammonium incorporated into rainfall, in Providence in 2018 to find that agricultural rather than city-based sources are most likely to blame for recent increases in urban ammonium levels.

“The ammonium we measured in precipitation has a significant non-local contribution, which does seem to be transported from what we believe to be agricultural regions,” said lead author Emmie Le Roy, who conducted research as a Brown University undergraduate and will begin a Ph.D. at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology this fall.

The levels of nitrate deposition, which come from nitroge-oxide emissions, in the Narragansett Bay area have decreased substantially in the past decades because of the federal Clean Air Act and other regulatory changes, according to co-author Emily Joyce, who published another paper on the topic last year.

Improvements in wastewater-treatment systems, too, have reduced nitrogen input to Narragansett Bay by nearly 60 percent, Joyce said. “That was definitely what they needed to focus on” to get a handle on the problem then, she said, but there’s been “nothing done to atmospheric deposition.”

Joyce’s atmospheric measurements, the first done in 30 years, showed ammonium deposition had risen to six times the amount in 1990.

“If there’s more ammonium, then there’s going to be more algae blooms and fish kills,” Joyce said. “And so from a water quality standpoint … you really want to figure out where that’s coming from and try to mitigate that.”

But to mitigate ammonium, regulators need to know where to focus their efforts — and this is what Le Roy’s research sought to address.

Her team studied the stable isotopes, or chemical signatures, of ammonium in more than 200 precipitation samples collected at Brown University from January to November 2018 to determine where the emissions came from.

“You can think of them as being sort of like a fingerprint that is distinct for different source types,” Le Roy said of the isotopic signatures.

Ammonium from close-range, urban sources, namely vehicle emissions and fossil-fuel combustion, would typically have a higher isotopic composition, according to Wendell Walters, Brown University associate professor and a co-author of the study. While ammonium from agricultural sources, including animal waste and fertilizer, would have a lower isotopic composition.

By scouring weather station databases, the team also found storm systems that developed over land carried significantly more ammonium than those originating over marine or coastal areas. This data supported long-range agricultural sources as the origin of ammonium deposits.

During the past seven decades global emissions of ammonia have more than doubled from 23 to 60 teragrams annually — one teragram is a billion kilograms or 2.2 billion pounds. Researchers say the increase is tied to rising ammonia emissions from industrial agriculture. The ability to grow crops depends on nitrogen, a critical plant nutrient. However, an overabundance of nitrogen, in animal waste and in excess fertilizer, can turn into gaseous ammonia.

When ammonia enters the atmosphere, it combines with pollutants — mainly nitrogen and sulfuric-oxide compounds produced by the burning of fossil fuels — to form fine-particle air pollution that can travel long distances.

Though the exact location is hard to pinpoint, Le Roy said wind patterns indicate that ammonium emissions are showering down onto Providence from states as far away as California, or even across the Pacific Ocean.

The wet deposition of ammonium is a global-scale problem, Walters said, and one that needs regulatory attention to prevent further acidification and eutrophication of sensitive ecosystems.

“It’s not something that the city of Providence could tackle on their own since there’s this large intrastate transport phenomenon occurring with the deposition,” Walters said. “But we may need to address the importance of incorporating ammonia regulations in the future — and that would have to be more at the national scale.”...

Caitlin Faulds is an ecoRI News journalist.

‘Most important fish in the sea’

Atlantic menhaden

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

Even though menhaden are eaten by few people, more pounds of the oily fish, often called “pogies” or “bunkers” by New Englanders, are harvested each year than any other in the United States except Alaska pollock.

The Atlantic menhaden fishery is largely dominated by industrial interests that remove the nutrient-rich species in bulk by trawlers to make fertilizer and cosmetics and to feed livestock and farmed fish. Commercial bait companies fish for menhaden to provide bait for both recreational fishing and for the lobster fishery. Recreational fishermen also access schools of menhaden directly and use them as bait for catching larger sport fish such as striped bass and bluefish.

This demand puts a lot of pressure on a species that plays a vital role in the marine ecosystem. For instance, juvenile menhaden, as they filter water, help remove nitrogen.

Conservationists often refer to menhaden as “the most important fish in the sea” — after the title of a 2007 book by H. Bruce Franklin. They believe that menhaden deserve special attention and protection because so many other species, such as bluefish, dolphins, eagles, humpback whales, osprey, sharks, striped bass and weakfish, depend on them for food.

This year’s spring migration of menhaden has brought a large influx of the forage fish into Narragansett Bay. As a result, there has been a marked increase in the number of fishing vessels and fishing activity there, according to the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (DEM).

Agency officials said members of its Law Enforcement and Marine Fisheries divisions are closely monitoring this fishing activity.

“Rhode Island relies on Atlantic menhaden in various capacities, such as supporting commercial harvesters, recreational fisheries and the Narragansett Bay ecosystem,” said Conor McManus, chief of the DEM’s Division of Marine Fisheries. “Through our Atlantic menhaden management program, which represents one of the most comprehensive plans for the species in the region, we have constructed a science-based program that strives for sustainable harvest.”

To prevent local depletion of menhaden and to ensure a healthy population of the fish remains in Narragansett Bay’s menhaden management area for ecological services and for use by the recreational community, the DEM administers an annual menhaden-monitoring program. From May through November, a contracted spotter pilot surveys the management area twice weekly to estimate the number of schools and total biomass of menhaden present.

Biomass estimates, fishery landings information, computer modeling and biological sampling information are used to open, track and close the commercial menhaden fishery as necessary. DEM regulations require at least 2 million pounds of menhaden be in the management area before it’s opened to the commercial fishery. If at any time the biomass estimates drop below 1.5 million pounds, or when 50 percent of the estimated biomass above the minimum threshold of 1.5 million pounds is harvested, the commercial fishery is closed.

Commercial vessels engaged in the Rhode Island menhaden fishery are required to abide by a number of regulations, including net size restrictions, call-in requirements to DEM, daily possession limits and closure of the management area on weekends and holidays.

Frank Carini: The vast poisoning that goes with maintaining lawns

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

The amount of pollution, from noise to air to water, created to maintain green carpets and immaculate yards is jarring. Lawn mowers, weed whackers, leaf blowers, pesticides, herbicides, fungicides and fertilizers. Much of this effort is powered by or made from fossil fuels.

Lawn-care equipment is typically powered by two-stroke engines. They are cheap, compact, lightweight, and simple. They are also highly polluting, generating up to 5 percent of the country’s air pollution, according to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

Each weekend for much of the year, according to estimates, some 54 million Americans mow their lawns. All this weekend grass cutting uses some 800 million gallons of gasoline annually. That doesn’t include the gas used to trim around trees and fences and to blow grass clippings around.

Those 800 million gallons also don’t include the gas used for lawns mowed during the week or by landscaping companies. It doesn’t include the oil that is also burned by these cheap engines. It doesn’t include grass cut on golf courses and along median strips and other public spaces covered by green carpets devoid of diversity.

A 2011 study showed that a leaf blower emits nearly 300 times the amount of air pollutants as a pickup. The EPA has estimated that lawn care produces 13 billion pounds of toxic pollutants annually.

This equipment is also noisy. Leaf blowers emit between 80 and 85 decibels, but cheap or mid-range ones can emit up to 112 decibels. Lawn mowers range from 82 to 90 decibels. Weed whackers can emit up 96 decibels of noise.

Electric lawn equipment is gaining in popularity and will slowly lessen the amount of fossil fuels burned to cut millions of acres of grass — a 2005 study found that about 40 million acres in the continental United States has some form of lawn on it. Electric equipment is also quieter than its gas-powered counterparts.

Much of the 90 million pounds or so of fertilizer dumped on lawns annually are fossil-fuel products. Nitrogen fertilizer, for instance, is made primarily from methane.

As stormwater carrying nitrogen and phosphorus from fertilizer runs off into streams and rivers and eventually into larger waterbodies such as Narragansett Bay, it impacts ecosystems and fuels algal blooms, some toxic, that suck oxygen from water.

On Rhode Island’s Aquidneck Island, for example, stormwater runoff carrying these nutrients is stressing coastal waters and contaminating the reservoirs that feed the Newport Water System.

The amount of toxic chemicals applied to lawns and public grounds annually to jolt grass to life and kill pests is staggering. This copious amount of poison, about 80 million pounds annually, is marked by white and yellow flags warning us not to let children or pets onto these monolithic spaces whose appearance trumps their health and that of the surrounding environment.

These warning flags are planted because of the 30 commonly used lawn pesticides 17 are probable or possible carcinogens; 11 are linked to birth defects; 19 to reproductive impacts; 24 to liver or kidney damage; 14 possess neurotoxicity; and 18 cause disruption of the endocrine (hormonal) system. Another 16 are toxic to birds; 24 are toxic to aquatic life; and 11 are deadly to bees.

Of course, these poisons don’t just kill or harm their intended targets.

While these chemicals hang around “feeding your lawn” or killing life, they are breaking down and working their way into the environment — until another application is applied, sometimes just a few weeks later, and the cycle repeats.

Poisons from these artificial fertilizers and the various -cides applied to lawns can seep into groundwater — contaminating drinking-water supplies — or turn to dust and ride the wind. They cling to people and pets who walk, run, and lie on treated grass. They get kicked up during youth sporting events.

These chemicals can be inhaled like pollen or fine particulates, causing nausea, coughing, headaches, and shortness of breath. For asthmatic kids, they can trigger coughing fits and asthma attacks.

Two of the most common pesticides, glyphosate used in Roundup and 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid (2,4-D) in Weed B Gon Max, have been linked to a number of health issues, including developmental disorders and cancer. The latter is a neurotoxicant that contains half the ingredients in Agent Orange, according to Beyond Pesticides, a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit.

The Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC) has called 2,4-D “the most dangerous pesticide you've never heard of.”

Developed by Dow Chemical in the 1940s, the NRDC says this herbicide helped usher in the green, pristine lawns of postwar America, ridding backyards of vilified dandelion and white clover.

Researchers have observed apparent links between exposure to 2,4-D and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and sarcoma, a soft-tissue cancer, according to the NRDC. It notes, however, that both of these cancers can be caused by a number of chemicals, including dioxin, which was frequently mixed into formulations of 2,4-D until the mid-1990s.

In 2015, the International Agency for Research on Cancer declared 2,4-D a possible human carcinogen.

Last year Bayer paid nearly $11 billion to settle a lawsuit over subsidiary Monsanto’s weedkiller Roundup, which has faced numerous lawsuits over claims it causes cancer.

Lawns are one of the most grown crops in the United States, but unless you are a goat or a dog with an upset stomach their nutritional value is zero. Yet the collective we continues to spend about $36 billion a year on lawn care.

Instead of putting public health at risk and degrading the environment with a chemically treated lawn, create a yard with a diverse mix of native trees, shrubs, and plants; it is cheaper to maintain, easier to take care of, environmentally beneficial, and more interesting.

Native plants support native wildlife and insects, are accustomed to the weather and soil, and are pest resistant. They support the pollinators of our food crops, clean the air and water, and help regulate the climate. They also make good natural buffers, which capture rainfall and filter stormwater runoff.

Frank Carini is editor of ecoRI News.

The first gasoline-powered lawn mower, 1902

URI creating computer models to assess how environmental change affects the ecosystem of Narragansett Bay

The Charles Blaskowitz Chart of Narragansett Bay published July 22, 1777 at Charing Cross, London

From ecoRI News

A team of scientists at the University of Rhode Island is creating a series of computer models of the food web of Narragansett Bay to simulate how the ecosystem will respond to changes in environmental conditions and human uses. The models will be used to predict how fish abundance will change as water temperatures rise, nutrient inputs vary, and fishing pressure fluctuates.

“A model like this allows you to test things and anticipate changes before they happen in the real ecosystem,” said Maggie Heinichen, a graduate student at the URI Graduate School of Oceanography. “You want to be able to prepare for changes that are likely to happen, so the model provides a starting point to ask questions and see what might happen if different actions are taken.”

Heinichen and fellow graduate student Annie Innes-Gold collaborated on the project with Jeremy Collie, a professor of oceanography, and Austin Humphries, an associate professor of fisheries. They used a wide variety of data collected about the abundance of marine organisms in Narragansett Bay, including life history information on nearly every species of fish that visits the area, and data about environmental conditions.

Their research was published in November in the journal Marine Ecology Progress Series. Additional co-authors on the paper are Corinne Truesdale at the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (DEM) and former URI postdoctoral researcher Kelvin Gorospe.

“We built one model to represent the bay in the mid-1990s, the beginning point of the project,” Innes-Gold said, “and another one that represents the current state of the bay. That allowed us to predict how the biomass of fish in the bay would change from a historical point to the present day and see how accurate the model was in its predictions.”

The model correctly predicted whether each group of fish or fished invertebrates would increase or decrease.

The students are now expanding the model using various fishery management scenarios and expected temperature changes to assess its outcomes.

“What if there was no more fishing of a particular species, for instance, or double the fishing? How would that affect the rest of the ecosystem?” Innes-Gold asked. “I’m also incorporating a human behavior model to represent the recreational fishery in Narragansett Bay. I’ve run trials on whether unsuccessful fishing trips affect whether fishermen will come back to fish later, and how that affects the biomass of fish in the bay.”

Heinichen is incorporating the temperature tolerance of various fish species into the model, as well as other data related to how fish behave in warmer water.

“Metabolism rates and consumption rates increase as temperatures go up, and this affects the efficiency of energy transfer through the food web,” she said. “If a fish eats more because it’s warmer, that affects the total predation that another species is subjected to. And if metabolism increases as waters warm, more energy is used by the fish just existing rather than being available to turn it into growth or reproduction.”

In addition, an undergraduate at Brown University, Orly Mansbach, is using the model to see how fish biomass changes as aquaculture activity varies. If twice as many oysters are farmed, for example, how might that impact the rest of the ecosystem?

The URI graduate students said that the models are designed so they can be tweaked slightly with the addition of new data to enable users to answer almost any question posed about the Narragansett Bay food web. They have already met with DEM fisheries managers to discuss how the state agency might apply the model to questions it is investigating.

“We’re making the model open access, so if someone wants to use it for some question yet to be determined, they will have the model framework to use in their own way,” Heinichen said. “We don’t know all the questions everyone has, so we’ve made sure anyone who comes across the model can apply it to their own questions.”

The Narragansett Bay food web model is a project of the Rhode Island Consortium for Coastal Ecology, Assessment, Innovation and Modeling, which is funded by the National Science Foundation.

Frank Carini: The partial recovery of the Seekonk River

Looking out at the Henderson Bridge over the Seekonk from Providence’s Blackstone Park

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

When driveways, highways, rooftops, patios and parking lots cover 10 percent of a watershed’s surface, bad things begin to happen. For one, stormwater-runoff pollution and flooding increase.

When impervious surface coverage surpasses 25 percent, water-quality impacts can be so severe that it may not be possible to restore water quality to preexisting conditions.

This where the Seekonk River’s resurgence runs into a proverbial dam. Impervious-surface coverage in the Seekonk River’s watershed is estimated at 56 percent. It’s tough to come back from that amount of development, but the the urban river is working on it, thanks to the efforts of its many friends.

The Seekonk River, from its natural falls at the Slater Mill Dam on Main Street in Pawtucket, R.I., flows about 5 miles south between the cities of Providence and East Providence before emptying into Providence Harbor at India Point. The river is the most northerly point of Narragansett Bay tidewater. It flows into the Providence River, which flows into Narragansett Bay.

While it continues to be a mainstay on the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management’s list of impaired waters, the Seekonk River is coming back to life.

“I started rowing at the NBC [Narragansett Boat Club] 10 years ago when I realized that I was on the shores really of a 5-mile-long wonderful playground,” Providence resident Timmons Roberts said. “I just think it’s a magical place, and seeing the river come back to life has meant a lot to me.”

The Narragansett Boat Club, which has been situated along the Seekonk River since 1838, recently held an online public discussion about the river’s recovery.

Jamie Reavis, the organization’s volunteer president, noted the efforts that have been made by the Blackstone Parks Conservancy, Fox Point Neighborhood Association, Friends of India Point Park, Institute at Brown for Environment and Society, Providence Stormwater Innovation Center, Save The Bay, and Seekonk Riverbank Revitalization Alliance, among others, to restore the beleaguered river.

“Having rowed on the river for over 30 years now, I can attest to their efforts,” Reavis said. “It was practically a dead river. It almost glowed in the dark back in the day. It is now teaming with life. Earlier this summer, a bald eagle flew less than 10 feet off the stern of my single with a fish in its talons. Watching it fly across the river and up into the trees is a sight I will not soon forget, nor is it one I could have imagined witnessing 30 years ago.”

Decades of pollution had left the Seekonk River a watery wasteland.

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries some of the first textile mills in Rhode Island were built along the Seekonk River. The river, and one of its tributaries, the Blackstone River, powered much of the early Industrial Revolution. Mills that produced jewelry and silverware and processes that included metal smelting and the incineration of effluent and fuel left the Seekonk and Blackstone rivers polluted.

There are no longer heavy metals present in the water column of the Seekonk River, but sediment in the river contains heavy metals, including mercury and lead.

Swimming in the Seekonk River, which doesn’t have any licensed beaches, and eating fish caught in it aren’t recommended because of this toxic legacy and because of the continued, although declining, presence of pathogens, such as fecal coliform and enterococci. The state advises those who recreate on the river to wash after they have been in contact with the water. It also advises people not to ingest the water.

But, as both Roberts and Reavis noted, the Seekonk River is again rich with life and activity. River herring, eels, osprey, cormorants, gulls and the occasional seal and bald eagle can be found in and around the river. The same can be said of kayakers, fishermen, scullers, and birdwatchers.

The river’s ongoing recovery, however, is threatened by rising temperatures, sewage nutrients and runoff from roads, lawns, parking lots, and golf courses in two states that dump gasoline, grease, oil, fertilizer, and pesticides into the long-abused waterway.

The Sept. 30 discussion was led by Sue Kiernan, deputy administrator in the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management’s Office of Water Resources. She has spent nearly four decades, first with Save The Bay and the past 33 years with DEM, working to protect upper Narragansett Bay.

She spoke about how water quality in upper Narragansett Bay, including the Seekonk River, has improved through efforts both large and small, from the Narragansett Bay Commission’s ongoing combined sewer overflow (CSO) abatement project to wastewater treatment plants reducing the amount of contaminants being dumped into the waters of the upper bay to brownfield remediation projects to the many volunteer efforts, such as the installation of rain gardens and the planting of trees, conducted by the organizations that sponsored her presentation.

She noted that nitrogen loads, primarily from fertilizers spread on lawns and golf courses, that are washed into the river when it rains, lead to hypoxia — low-oxygen conditions — and fish kills. Since 2018, six reported fish kills that combined killed thousands of Atlantic menhaden have been documented by DEM’s Division of Marine Fisheries in the Seekonk River.

Kiernan said excessive nutrients, such as nitrogen, stimulate the growth of algae, which starts a chain of events detrimental to a healthy water body. Algae prevent the penetration of sunlight, so seagrasses and animals dependent upon this vegetation leave the area or die. And as algae decay, it robs the water of oxygen, and fish and shellfish die, replaced by species, often invasive, that tolerate pollution.

While these nutrient-charged events remain a problem, she said, the overall habitat of the Seekonk River is improving. Kiernan noted that in recent years some 20 species of fish, including bluefish, black sea bass, striped bass, scup, and tautog, have been documented in the river.

The Seekonk River is still a stressed system, but Kiernan said the river is seeing a positive trend in its recovery.

“We’re not in a position to suggest that its been fully restored, and honestly I don’t think that we’ll be in a position to do that until we get the CSO abatement program further implemented,” she said. “But I think you can take some satisfaction in knowing that there are days where things look OK out there.”

Frank Carini is editor of ecoRI News.

Grace Kelly: What's meant by the 'blue economy'?

The area within red is Narragansett Bay.

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

Blue is the new green.

The term “blue economy” has been popping up in headlines and economic outlines with increasing frequency during the past 10 years. But what exactly does blue economy mean? And what does it specifically mean for Rhode Island, the self-proclaimed Ocean State? And, to further complicate matters, what does it mean in a COVID-19 world?

A report released in March by the University of Rhode Island Graduate School of Oceanography, URI’s Coastal Resources Center, and Rhode Island Sea Grant attempts to answer the first two questions — the coronavirus pandemic hadn’t yet emerged during the report’s research period.

Jennifer McCann, director of coastal programs at the Coastal Resources Center, said that state government asked her team to define Rhode Island’s blue economy.

“So I Googled it, of course, and you get the definition from the U.N. and from other big, global programs and from different countries, and then you look at the definitions from different states like California and Michigan, and then you can go down further, and even Cape Cod has a definition of the blue economy,” she said. “Then our team looked at what data was out there, and we interviewed more than sixty people to figure out what they thought Rhode Island’s blue economy is, and so now we have a different definition than anyone else.”

Turns out Rhode Island’s blue economy, which the report defines as “the economic sectors with a direct or indirect link to Rhode Island’s coasts and ocean — defense, marine trades, tourism and recreation, fisheries, aquaculture, ports and shipping, and offshore renewable energy” — has a boatload of potential.

According to the 86-page report, 6 percent to 9 percent of Rhode Islanders work within the state’s ocean-based economy, which is valued at more than $5 billion.

Each sector listed in the report’s definition brings its own strengths to the table.

Ocean-based tourism raked in a whopping $703.6 million in 2018.

According to a 2019 study by Bryant University, the shipping industry at the Quonset Business Park generates nearly 7 percent of the state’s gross domestic product.Narra

The defense industry in Rhode Island uses certain areas of Narragansett Bay as testing grounds for new underwater technologies.

“The U.S. Navy owns an underwater tracking range located in Narraganset Bay. It is a testbed for undersea technology prototypes,” Molly Donohue Magee, executive director of the Middletown-based Southeastern New England Defense Industry Alliance, wrote in an email to ecoRI News. “The Naval Undersea Warfare Center has hosted an annual event, Advanced Naval Technology Exercise (ANTX) where companies can demonstrate their technology and prototypes to Navy engineers and the fleet.”

She goes on to note that ocean technology is the next big thing, and it will provide the state with an opportunity to strengthen its blue economy.

“Rhode Island is the hub of undersea technology,” she wrote. “It’s the home of the Naval Undersea Warfare Center, the Department of Defense’s research laboratory for undersea technology. There are many companies in Rhode Island and the region with unique technology related to the undersea environment. The ocean is the next frontier.”

Catherine Puckett is the owner of the Block Island business Oyster Wench, a shellfish and kelp farm operation. (Coastal Resources Center)

Deep blue economy

In addition to the obvious sectors of the blue economy, McCann made sure to note there are parts of it that might not seem so apparent, like advocacy groups such as Save The Bay or state agencies such as the Coastal Resources Management Council (CRMC).

“[Y]ou can’t forget about the marine-focused advocacy and civic groups,” McCann said. “And then you look at the role our government agencies have been playing whether it be Real Jobs RI working directly with marine trades and defense and building capacity, or CRMC who is designing our coast so we can have a pristine environment as well as a working waterfront.”

A big takeaway from the recent report, as well as from the state’s most-recent long-term economic development plan, which was approved in January, is that there is room for improvement.

During a January Rhode Island Commerce Corporation meeting that discussed the long-term economic development plan, titled Rhode Island Innovates 2.0 and written by Bruce Katz, Gov. Gina Raimondo is quoted as saying, “Basically, his analysis is: ‘Listen, you’ve made a lot of progress the past few years. But still a relatively small portion of our economy is what I would call advanced — high wage, high skill.’”

The governor went on to say that the state needs to do more to advance the education and skill of the average Rhode Islander.

Tide is high

While growing the blue economy was already seen as somewhat of an uphill battle, the coronavirus pandemic has thrown another obstacle in the way.

For instance, as of April 24, Discover Newport, a nonprofit dedicated to promoting the city of Newport and its ocean-centric tourism industry, had laid off 18 of its 22 employees, and expects to see a fall in annual revenue from $3.7 million to a little over a $1 million.

A variety of organizations that fall within the blue economy, such as Rhode Island Marine Trade Association, the Rhode Island Hospitality Association, Polaris MEP, and the Southeastern New England Defense Industry Alliance, have recently banded together to try to revive the economic momentum lost.

For McCann, this collaboration was always essential to a thriving blue economy, even before the virus took its economic and public-health toll.

“We need to work together,” she said. “That’s the way we are going to sustainably grow our state. If we just focus on economics or higher-ed, we’re not efficiently moving forward for sustainable growth in our state.”

Grace Kelly is an ecoRI News reporter.

Left doors unlocked

In the old-fashioned downtown of East Greenwich, R.I. on Narragansett Bay

“We moved around a bit when I was younger, but I grew up primarily in Rhode Island, in a beautiful seaside community called East Greenwich. It was a small town, and so safe that we rarely locked our doors at night.’’

— Michelle Gagnon, crime novelist

The Silver Age

Looking across the head of Narragansett Bay to Providence from the East Providence shoreline.

— Photo by William Morgan

Grace Kelly: Warm-water fish have been moving into Narragansett Bay

Sea robins are one of the species that have been moving in as Narragansett Bay warms.

From ecoRI News (ecori.org)

On a normal Monday morning, University of Rhode Island graduate student Nina Santos would head to the Wickford Shipyard, in North Kingstown, R.I., pull on some waterproof gear, and board the Cap’n Bert.

“My dad was a fisherman, so I grew up around fishing and boats but I had never been out on the water on a fishing boat before,” she said. “I had been on my dad’s fishing boat when it came to port but never out on the water, so now I feel like I’m getting to experience what he did for a living.”

Santos and the boat’s captain, Stephen Barber, would normally set sail around 8:15 a.m., measuring the water temperature, oxygen, and salinity levels, and then casting a net out at various checkpoints. They would pull up the net after 30 minutes of cruising at 2 knots, then identify, group, measure, and weigh the fish they caught before tossing them back. This would continue for about 4 hours, before Barber would turn the Cap’n Bert around at Whale Rock and slip back into the Wickford Shipyard around 12:15 p.m.

But the past month or so of Mondays have been anything but normal. The coronavirus hasn’t only shuttered universities around the world, it’s also shuttered much of researchers’ field work, and for Santos, that means a gap in URI fish-trawl records dating back to 1959.

“It’s kind of sad to have this big data gap in the trawl survey but it’s not the first time it’s happened,” Santos said. “So, I don’t think it will change too much, but it is a little bit sad because now is when we would actually see things moving back into the bay.”

Before the coronavirus derailed the weekly trawl, Santos was continuing a 61-year legacy of scooping fish out of Narragansett Bay to paint a picture of its inhabitants.

The story of the fish trawl starts, appropriately, with a couple by the name of Fish.

Charles Fish and his wife, Marie, were longtime members of the marine biology community with a long list of accomplishments: Marie collected and studied fish and marine sounds; Charles was a pioneer in the study of zooplankton. In 1925, the couple were a part of an expedition to study the Sargasso Sea led by naturalist and explorer William Beebe.

Charles and Marie Fish attending the dedication of the Narragansett Marine Laboratory in 1948. (URI)

But their lasting legacy lies in the creation of the Narragansett Marine Laboratory, which opened 72 years ago, as a part of the School of Arts and Sciences at Rhode Island State College — what would become URI — and in a fish trawl that has collected an astounding amount of data.

“The goal was to measure the seasonal occurrences and abundance of fish in the bay,” said Jeremy Collie, a professor of oceanography at URI who runs the program today. “Part of it was to catch the fish that were in the bay from week to week and actually be able to identify them, and perhaps link that with the soundscape that Marie Fish was hearing.”

Collie took the helm of the program in 1998, after H. Perry Jeffries retired. Jeffries was one of Fish’s original assistants, who took over the program in 1966 after Fish retired.

“Jeffries was one of the first assistants, and when he got the job here as a professor, he decided he would keep the program going. It was really Perry who started looking at the longer-term trends of the fish populations,” Collie said. “When he retired, I took over and the longer we keep going, the more interesting it becomes. It’s a very rich data center.”

While the program has noticed changes in local marine populations, including a shift from fin fish species to more invertebrates such as crabs and lobsters, one of the biggest differences over time has been the introduction of many more warm-water species.

“Since the year 2000, it’s become more and more obvious that it’s the changing climate that is affecting fish populations,” Collie said. “The community is shifting because the cold-water species are less abundant than the warm-water species, which are way more abundant. That’s the big signal that we are measuring.”

Santos has noticed this shift, especially during her wintertime trawls.

“We’re not really catching much right now; it’s surprising how little we do catch. There’s such a disparity between the winter catch and the summer catch, and I think that part of that is the shift that Narragansett Bay has had towards warm-water species,” she said. “There’s not really anything left once winter hits; all the species that would have been here in the winter in the cold waters are not around anymore. They’ve moved north.”

Some flashy examples of warm-water visitors include orange tilefish, sand tiger sharks, and an errant sailfish. There also are two warm-water residents of Narragansett Bay that are so common you might think they were native species: striped sea robin and scup.

“We’ve been studying the striped sea robin in particular because we’re interested in the impact they have on the fish community,” Collie said. “Sea robins kind of swim around on the bottom, vacuuming up everything that’s in their path, and so we’re trying to estimate their impact on the community, on the invertebrates and the fish they may be eating. So, it’s not only that these species are changing in abundance and increasing, they are also having an effect on the food web.”

As for scup, there is a healthy population of the fish also known as porgy in Rhode Island waters. In 2017, the state landed more than 6 million pounds of the bony fish.

For Collie, the reason for its abundance lies in the warming of Narragansett Bay.

“The easy answer to why there are so many is that they’re a warm-water species, and the water is getting warmer so there are more of them,” he said. “The scup population as a whole, coast-wide, is in good shape. There’s a healthy scup population out there.”

As the bay has warmed, with the surface temperature on Jan. 25, 1959 registering 33 degrees Fahrenheit and on the same day in 2017 registering 40 degrees Fahrenheit, the URI trawlers have been there to document it, and they will continue to do so — once the pandemic is squashed.

Grace Kelly is a journalist with ecoRI News.

Todd McLeish: Invasive crab is stressing New England lobster populations

Asian shore crab.

Via ecoRI News (ecori.org)

Speculation about the cause of the decline of lobster populations in Narragansett Bay has focused on an increasing number of predatory fish eating young lobsters, warming waters stressing juveniles, and a disease on their shells that is exacerbated by increasing temperatures.

A new study by a scientist at the University of North Carolina points to another contributing factor: Asian shore crabs, which originated on the shores of the Pacific.

The crabs were first observed on the coast of New Jersey in 1988, where they probably arrived in the ballast of cargo ships. They quickly expanded up and down the East Coast — arriving in Rhode Island in 1996 — and they are now found at densities of up to 200 per square meter in the intertidal zones of southern New England.

“If you flip over a rock, it’s like going into an old basement and turning on a light and watching the cockroaches scatter,” said Christopher Baillie, who conducted the study as a doctoral student at Northeastern University. “They’re really abundant.”

The dramatic increase in the density of Asian shore crabs in the region was followed by a massive decline in the density of green crabs. Green crabs are also not native to the region, having been introduced more than 100 years ago, “but it’s an indication of what the Asian shore crab could be doing to native species,” Baillie said.

Adult lobsters live in much deeper water than the shallow intertidal zone inhabited by Asian shore crabs, so the two species seldom interact. But some larval lobsters settle in the intertidal and subtidal zones, which they use as nursery habitat. Prior to the arrival of Asian shore crabs, it was an area that had fewer predators and an abundance of food. But now the young lobsters are finding themselves in competition with the crabs for food and shelter.

When Baillie surveyed the shoreline in Nahant and Swampscott, Mass., over a five-year period, he found a dramatic increase in the density of Asian shore crabs concurrent with a decrease in the density of juvenile lobsters. He then conducted several laboratory experiments that found that smaller juvenile lobsters lost out to the crabs when competing for food and shelter, especially as the crab numbers increased.

“We saw that the presence of Asian shore crabs significantly reduced the amount of time the lobsters were able to spend in the shelter,” Baillie said. “The more crabs we introduced, the more times the lobster was displaced. When the crabs were at higher densities, the lobsters spent the entire time fleeing from predation attempts by the crabs.”

In similar tests, lobsters that were slightly larger than the crabs were able to obtain food and shelter, but the lobsters fed more frequently and ate faster in the presence of the crabs.

“It appeared that they perceived the crabs as a competitor, and sometimes the lobsters even attacked the crab,” Baillie said. “So while that sized lobster was the dominant competitor, there is a potential energetic cost to battling the crab as well as a potential for injury in those battles.”

According to Niels-Viggo Hobbs, a lecturer and researcher at the University of Rhode Island who studies Asian shore crabs, Baillie’s research confirms what many scientists have suspected: the crab has a substantial negative impact on young lobsters.

“There are still a lot of unanswered questions,” he said. “There may also be a positive impact for lobsters. The crabs may provide a food source for adult lobsters. Lobsters love to eat smaller crustaceans. The take-home message for me is that even when we talk about invasive species, we can’t always say they’re 100 percent bad.”

Although the crabs arrived in Rhode Island waters at about the same time that lobster numbers began declining in Narragansett Bay, Hobbs said it’s unclear if the crabs were a major factor in lobster decline.

“The problem is that on top of Asian shore crabs showing up, we also had lobster shell disease, increasing water temperatures, and other factors working to make life for lobsters more difficult,” Hobbs said. “The Asian shore crab certainly didn’t help. It’s difficult to say how bad an impact it had, but it was certainly poor timing if not worse.”

The long-term implications of Baillie’s study are unclear, since most lobster nursery grounds are in deeper waters than where Asian shore crabs are found.

“But as the crabs continue to expand their range into the northern Gulf of Maine, there is potential for further interactions with juvenile lobsters,” Baillie said. “And while there’s a number of things going on with lobster populations, we’ve shown that the Asian shore crabs may be reducing the value of this nursery habitat for lobsters.”

Unfortunately, there is little that can be done about the invasive crabs. They are occasionally used as bait by tautog fishermen, but not enough to affect population numbers. They are too small to be a valuable commercial fishery. A parasite in the crab’s native range in East Asia is believed to castrate the crabs, rendering them unable to reproduce, but releasing the parasite in local waters would likely cause more harm than good.

“It would be incredibly dangerous to go down that rabbit hole,” Baillie said.

“The crabs are established and here to stay,” Hobbs noted. “So the best we can do is keep an eye on how they impact our native species, and then hope that maybe there’s some good that comes out of it.”

Baillie hopes his study will at least draw attention to the effects the crabs have and prompt government leaders to prioritize what he calls “fairly simple changes in policies” — like requiring the discharge of ballast water in the open ocean — that could be implemented to prevent future introductions of invasive species to the local marine environment.

Rhode Island resident and author Todd McLeish runs a wildlife blog.

Tim Faulkner: On the edge in Narragansett Bay

Narragansett Bay.

Via ecoRI News (ecori.org)

This year’s Watershed Counts report again describes a bay and shoreline under duress and facing an uncertain future. The causes aren't new, but the overarching threat to the Narragansett Bay region is climate change. To illustrate the current and future perils, the report analyzes three topics: oysters, saltwater marshes and waterfront homes. The three make for an ideal summer setting in Rhode Island, but from an ecological perspective they are on the cusp of significant change.

Marshes

The report's profile of saltwater marshes is compelling for its clear illustrations and concise description of one of Narragansett Bay’s most underappreciated resources. Marshes teem with ecological diversity and provide important functions such as sequestering carbon, filtering pollution, and protecting the shoreline from floods and erosion.

Yet, sea-level rise is submerging these habitats faster than they can naturally elevate themselves. Since 1999, the water level in the bay has risen 3 inches, compared to a 1.125-inch accretion rate for marshes. As water becomes trapped atop marshes, the grasses turn to mudflats and eventually open water. According to the report, if sea-level rise increases 5 feet, as projected, the bay will lose 87 percent of its remaining marshes.

Experimental marsh preservation projects are underway in Middletown, Charlestown and Narragansett, R.I. To elevate marshes, sediment from dredged navigation channels and breachways is sprayed on top of the grasses. But the report acknowledges the it will be a challenge to keep up with the inevitable.

“Even if emissions were halted today, it could be at least a hundred years for ocean temperatures and seal level rise to change course," according to the report.

Oysters

Oyster farming is a re-emerging industry that reached its peak in 1922, when farms covered 22 percent of Narragansett Bay. Although oyster farming is a fraction of the size today, they are the state’s largest source of shellfishing revenue. The industry is projected to grow, thanks to strong oversight and management plans from state agencies such as the Coastal Resource Management Council (CRMC) and Department of Health. But warming water impacts spawning, alters the taste of oysters and escalates the likelihood for diseases. Climate change also increase stormwater runoff, which pollutes the bay and leads to shellfish closures.

Even with these threats, however, the report concludes that oyster farming can grow and thrive.

“Rhode Island is well positioned to identify and manage current and future impacts of climate change to the oyster aquaculture industry," according to the report.

North Kingstown, for one, has partnered with state institutions to map and assess the town’s vulnerability to projected sea-level rise. (CRMC)

Waterfront homes

The pursuit of waterfront property is coming back to haunt Rhode Islanders. The development of the coast has destroyed marshes and hardened the shoreline with manmade barriers such as seawalls.

Since the 1970s restrictions have slowed building on marshes and construction of artificial barriers. But with 30 percent of the the bay's shoreline “hardened” by development and rising seas there isn’t much room for nature to adapt or help lessen the force of more powerful storms and erosion wrought by climate change.

Waterfront property owners have to make expensive decisions. Retreat, elevate their homes, or install natural buffers to protect against the inevitable damage expected from the encroaching ocean.