'A primal presence'

“Half Tree” (oil on canvas), by Barbara Groh, at Gallery Sitka, Newport, R.I.

She says in her artist statement:

“My visual inspiration began early with Abstract Expressionism. As I am primarily an abstract artist, I aspire to have my work affect others as I have been by provoking thought, emotional experiences, moods, and aesthetic pleasure.

“Landscape is a primal presence for me. I explore by walking in diverse environments and return to the studio to transform my experiences into physical being. These inspirations can happen just outside my studio door or in distant lands with unfamiliar landscapes and cultures.

“My paintings in oil, acrylic, or cold wax may reflect a quiet practice of noticing inner space, peace, and presence, while others may reflect a desire and will to express freedom and unencumbered thought. Both encompass the moment and the past – a synthesis of physicality, perception, meditation, and inner movement.’’

Founders Hall at the U.S. Naval War College, in Newport.

Llewellyn King: Capitalist solutions to the housing crisis

The Royal Mills complex, in West Warwick, R.I., a former textile factory that was converted to 250 residential apartments.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

The housing crisis, which is spread across the United States, is most easily measured in the human cost. At the low end that is families, working families, forced to go without a roof, to live in cars, on the streets, and in tent cities or municipal shelters.

But there are other costs, mostly to young people; costs like getting married and having to live with parents or living in a group house long past the age when that is an adventure.

A big cost of the housing crisis is labor mobility.

One of the great strengths of the American workforce has been its preparedness to relocate to the work, unlike parts of Europe where the workers have demanded that the work come to them.

It was this mobility that fed the growth of California and today is feeding the growth of Texas, although housing stress — particularly in Austin, the dynamic capital — is beginning to be a problem there.

Mobility is a feature that made America America: its restlessness, its sense of seeking the frontier and moving there.

According to Dowell Myers, a professor of policy, planning and demography at the University of Southern California, whom I recently interviewed on the television program White House Chronicle, 21 percent of the population relocated every year, now it is down to 8 percent.

According to Myers and other experts, the housing shortage has been building since the Great Recession of 2008 to 2009. This has been multifaceted and includes a shortage of money available for lending to builders, labor shortages, supply chain disruptions, but particularly local exclusionary laws.

To my mind, and to architects and developers I have spoken to, those laws are the biggest problem: the mostly smug, leafy suburbs don’t want new townhouses or apartments. That introduces underlying issues of class and race. In the suburbs, two of the most dreaded words are “affordable housing.”

The answer is to build “luxury” housing rather than designated low-income housing, according to Myers. It is a view I have espoused for years. Build upscale housing that caters to the middle class and as people move up, more housing will become available at the bottom. It is capitalism at its simplest: supply and demand at work. At present we have too much demand and not enough supply.

An extraordinary thing about the housing crisis that is crippling the nation and changing its social as well as its labor dynamics, is why isn’t this a prominent issue in this presidential election year.

It is an issue that could bolster candidates because there are things at the federal level which can be done. Here is a problem that affects all. Where are the political solutions coming from the top? Where are the political reporters asking the candidates, “What are you going to do about housing, a here-and-now crisis?”

Public housing comes pre-stigmatized. The answer is the market. It isn’t a free market because it is inhibited by the fortress-suburb mentality, but there is enough room for the market to accelerate, to build more houses with just a little federal incentive.

Some of the most attractive homes in New England are in converted mills and factories. These grand structures have been turned into what realtors call “residences.”

The use of the word residences, instead of apartments, denotes something desirable. So be it: If it works, do it.

Much of the rehabilitation of the industrial properties in New England, and across the country, has gone in tandem with tax incentives. In one case, these were enough for the developers to produce 250 apartments from one historic mill in Rhode Island. (See photo.) Up and down the country there are abandoned industrial properties that require little zoning hassle to be repurposed.

USC’s Myers, who says every kind of housing is needed, points out that building for those who can afford to buy works in another way: It inhibits gentrification and the social upheaval, as the poor are pushed out of their old neighborhoods, something which, by the way, has been very apparent in Washington, D.C.

The use of urban space is changing, shopping centers are failing and office buildings are losing their luster, and that means housing opportunities. Repurposing isn’t the only answer, and a lot of new housing is needed, but there is huge evidence that repurposing works from the factories of New England to the lofts of Manhattan — desirable housing has been created from the debris of the past.

Building anything anywhere isn’t a simple matter, but once the financial incentives are gotten right, things begin to move. It will take decades to fix the housing problem, but that should be accelerated now.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island.

Offshore wind-power battles keep coming

“50 m” means mean wind speed at 50 meters above the ground or water.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

As usual, whatever the huge environmental and economic benefits of green-energy projects, some people try to block them, especially affluent folks who don’t want to look at them or even if they can’t see them hate the very idea of being anywhere near them. Sometimes the blocking attempts are on their own, and sometimes they get the help of the fossil-fuel industry. (Hey, who wants competition?!) Consider that a far-right (euphemism – ‘’libertarian”) Trump-connected outfit called the Caesar Rodney Institute, with ties to the oil industry, is one of the groups fighting offshore wind projects.

The latest example in these parts is a bunch of people in the Cape Cod town of Barnstable trying to stop electrical cables from the offshore wind farms of Commonwealth Wind and Park City Wind from being laid 50 feet under beaches.

The foes like to cite alleged health risks from electromagnetic fields and fires. But in fact putting these cables deep underground is the safest way to go. How many of these opponents have complained about the risks from overhead lines, which produce -- obviously! --far, far more human exposure to electromagnetic fields than can underground cables, require cutting down wide swaths of woods and otherwise disturbing the environment to make space for them and can (albeit rarely) cause fires, of which California is the most dramatic example.

There have long been underground cables all over America that carry the same voltages that would come from these offshore wind projects. And cables from offshore wind farms in Europe have been put under beaches without incident, but it’s a lot easier to do such projects there than here.

Hypocrisy makes the world go round.

And now some powerful folks in Newport seek to block wind turbines in the water far off that city. One foe is self-described “Trumpette’’ Dee Gordon, whose properties, with her husband, include a place on Ocean Drive.

Of course plenty of people, Trumpette or otherwise, don’t want wind turbines near them.

Hit this link, this one and this one. And this one.

And this one. And, finally, this one.

I hope that Massachusetts officials will favor the broad public interest and not let local opposition block what would be an environmental and economic boon for our region. But lots of people still seem to prefer burning oil, gas and coal from outside our region rather than putting up with nonpolluting, locally produced energy.

Blue but happy

“Happy Dance” (encaustic and ink painting), by Nancy Whitcomb, in the “Out of the Blue” group show, at Spring Bull Gallery, Newport, R.I., through Oct. 29

Kevin Gilmore, the show’s juror, says:

“A word on ‘Out of the Blue’. The color blue is the first ‘clue’ in the prompt for this exhibition. Not surprisingly, for a gallery located on Aquidneck Island, surrounded by the beautiful shorelines and waters of Narragansett Bay, the color blue dominated the group of submissions.’'

Pay ‘em to clear out?

Aerial view of Holland-low Barrington, R.I., in 2008

— Photo by Brian McGuirk

How Much to Pay Them?

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

As the sea level rises, and coastal storms seem to be becoming more severe, more and more states and localities are realizing that in many stretches of low-lying coast, the only long-term solution is to remove houses and other structures, in what has been called “managed retreat.’’ The tricky thing is how to pay for it, especially since shoreline houses tend to be expensive.

Should homeowners who, after all, presumably know (or should know) the risks of owning waterfront property be compensated with tax money for being forced to leave their houses to be demolished or to pay them to move their houses?

Get ready for buyouts, relocating roads and changing zoning ordinances and districts. This could be particularly exciting in towns, such as Warren and Barrington, R.I., where so much of the land is barely above sea level.

A lot of shoreline homeowners, who include a disproportionate number of politically powerful rich people, will be, er, inconvenienced. And towns and cities will worry about the loss of property-tax revenue.

Localities, led by new state policies, should start planning where, or if, buildings and public infrastructure can be relocated, and meanwhile promote marshland expansion, which will help mitigate flooding in stores.

This should be done with all deliberate speed. Global warming is speeding up.

Llewellyn King: Fall down before a Frankenstein deity

How deep learning is a subset of machine learning and how machine learning is a subset of artificial intelligence

— From British Wikipedia

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Those who work with language have reason to worry about the effect of artificial intelligence and its awesome skill with words.

You can, for example, ask ChatGPT to write an article on almost any subject, and it will mostly come back with something ready for the page, untouched by a human editor. If you want it in Washington Post style and it is in Guardian style with British spelling, faster than you can type in the request, it will reformat the article into the style and usage you want and, presto, it is ready to print or publish digitally.

Writers, lawyers and college professors will feel the sting first. Writers in Hollywood are on strike because of the threat posed. College professors are going into the new term unsure whether they will deal with original work or whether students are substituting AI-generated essays and theses.

Journalists, already reeling from the closure of so many newspapers, are wondering about their future.

But what about religion?

AI ramifications in organized religion are good and bad. In fringe religions and cults, it will be open season on worshipers. And some will find comfort in speaking to God as though the Almighty is resident in AI.

On the good side, many pastors approach Sunday in trepidation. The sermon, which is supposed to be instructional, uplifting and erudite, is a source of torture to those who aren’t good writers or have difficulty sharing their own faith with the congregation.

There are newsletters to help sermon writers and a wealth of diocesan support. Still, sermons are a trial for many pastors. You can read an old sermon or plagiarize another cleric, but that leaves sincere preachers feeling they are cheating and letting their congregants and their mission down.

Enter AI. By feeding a few thoughts to a chatbot, a polished sermon incorporating some of the preacher’s ideas appears almost instantly.

This hasn’t been wasted on the established churches, I learn from the BBC. The churches are looking at ways of embracing AI, using it as a tool, a gift to help with preaching and pastoral work, comforting the sick, composing notes of sympathy, and research.

The rub comes when people, as some surely will, confuse concepts of God with AI simulations and start to think that AI is a deity.

It has the characteristics usually associated with a deity: ubiquitous and seemingly all-knowing.

Indeed, it may claim to be a god if it hallucinates, as it sometimes does. What, then, for the unsuspecting? Do they fall to their knees?

I asked ChatGPT, and it sent me a 10-point list of the possibilities, noting that it is a subject that is complex and evolving.

These three points are scary:

—“Customized Spiritual Experiences: AI algorithms could be designed to tailor spiritual experiences to individual preferences and beliefs. These experiences might include personalized prayers, meditation sessions, or virtual pilgrimages, designed to resonate with each person’s spiritual inclinations.”

—“Ethical Dilemmas and Moral Guidance: AI might be used to explore complex ethical questions and provide guidance based on religious teachings. For instance, AI systems could analyze various religious perspectives on a given moral issue and help individuals navigate their choices.”

—“Exploration of Spirituality and Philosophy: AI’s ability to process vast amounts of information could be harnessed to delve deeper into philosophical and spiritual questions, potentially offering new perspectives on the nature of existence, consciousness and the divine.”

Would it be safe to call it Frankenstein worship?

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS.

Dartmouth Hall at the eponymous college in Hanover, N.H.

Editor’s note. This is from the Council of Europe:

“The term ‘AI’ could be attributed to John McCarthy of MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology), which Marvin Minsky (Carnegie-Mellon University) defines as ‘the construction of computer programs that engage in tasks that are currently more satisfactorily performed by human beings because they require high-level mental processes such as: perceptual learning, memory organization and critical reasoning. ‘ The summer 1956 conference at Dartmouth College (funded by the Rockefeller Institute) is considered the founder of the discipline. Anecdotally, it is worth noting the great success of what was not a conference but rather a workshop. Only six people, including McCarthy and Minsky, had remained consistently present throughout this work (which relied essentially on developments based on formal logic).’’

Llewellyn King: We're lonely in our boxes

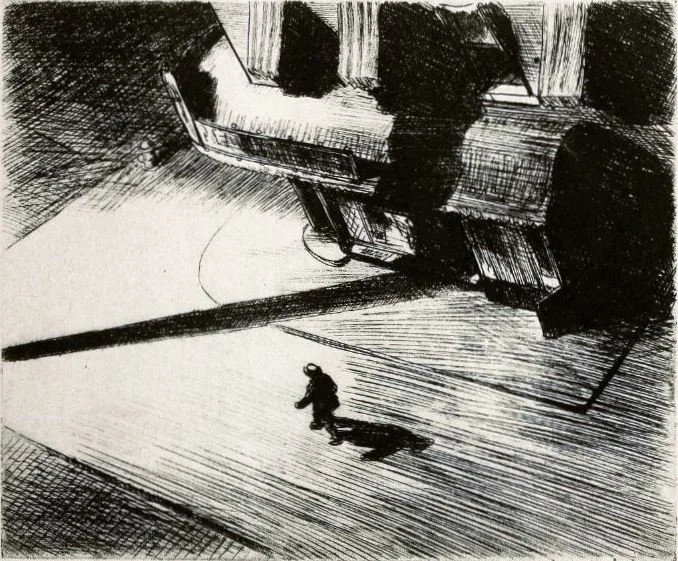

“Night Shadows’’ (1922 etching), by Edward Hopper, created for the magazine Shadowland.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

The nation, I read, is in the grip of a loneliness epidemic.

This has all been made worse, one suspects, by the effects of the pandemic-induced lifestyle changes — consequences of the forced isolation that changed social and work practices in ways that haven’t changed back.

Other changes have been coming slowly over the decades, but all add to the lonely life. The way of life has had a trajectory for those who live alone, which has increased the possibility of loneliness.

We isolate ourselves in ways that are new or only decades old. We drive alone. We live in a house or apartment, if single, alone. We work alone in that dwelling, facing a computer or watching a movie on television alone.

I call this the box culture: We drive in a box, live in a box, and, as likely as not, stare into a box as we work.

Changing work patterns are probably a critical part of the structural loneliness that is now rampant. Even if one doesn’t work at home, we work differently. We used to make contacts, and often new friends, by doing business on the telephone. Now we shoot off an email and maybe, if it can’t be avoided, make an appointment to make a video call with several people.

We have wrung out all spontaneity. Making friends is a kind of spontaneous combustion. You might as well be doing business with AI for all the lack of warmth or humor in today’s work interactions.

Then there are work friends. For most of us, it was at work or through work that we made our friends — that is, if they weren’t carryovers from school or college.

People who work together and play together fall in love, sometimes get married, and sometimes meet a friend who undoes a marriage. There is a lot of sex at places of work, although companies might deny it. Note the number of CEOs who marry their assistants.

Another feature of the loneliness structure is that pub life is in decline. The local tavern, even for non-drinkers, was part of the way we lived, and drinking isn’t as pervasive as it once was.

Time was when after work or wishing to see a friend, you went for drinks. People gave drinks parties at noon on weekends: no food, just a convivial glass. That isn’t extinct, but it isn’t what it used to be.

Drinking oils society’s wheels but of course too much, and the wheels come off. Go sit at the bar, and someone will talk to you. There is camaraderie in a saloon.

Entertaining has become more formal. Blame all those cooking shows on television. People don’t have friends over for a hamburger anymore. No. They have to have Steak Diane and a soufflé — a meal with the stamp of Julia Child on it. Result: less dropping in on friends, more isolation.

Of course, there are those who are lonely because of bereavement, sickness, old age and family abandonment. But those things have always been with us. They really suffer loneliness, feel the terrible blanket of isolation.

For those who have decided it is too strenuous to go to the office, that the phone is for messaging, that home loneliness is inevitable because we can’t cook or are ashamed of our homes, join something: a church, a theater group, a book club or do volunteer work.

Much of loneliness, from what I can divine, is a product of how we live now. We sit in our boxes inadvertently avoiding others. Television isn’t friendship, drinking alone isn’t companionship. Go shopping in a store, go to church, go to the pub, work in the food bank, join a book club. As the old AT&T advertisement used to say, “Reach out and touch someone.”

No one can predict how or where great friends or great loves will be found, but certainly not staring at a computer.

Several of my greatest friendships are a result of people who have taken violent exception to something I have written and wanted to meet up to berate me. The facts were wrong. I was evil, I met them to take my medicine, as it were, and parted knowing a new friend.

Surgeon Gen. Vivek Murthy has raised the issue of loneliness. He would be advised to tell people to look at lifestyle. Does it have loneliness baked in?

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. He’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

White House Chronicle

Llewellyn King: Despair and danger

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Body language is the new political voice in America.

The language is universal and easily learned because it has just four components: eye-rolling, sighing and shrugging, accompanied by turning hands up.

“Oh my God, it’s a disaster,” is one translation. Another might be, “Don’t ask me, I didn’t sign on for this.”

It belongs — this silent expression of despair about the presidential election, unfolding for 2024 — to old-line Republicans and to a wide swath of Democrats, too.

Political discussion has ended in these groups, replaced by the kind of fatalism summed up in the words of the Irish poet William Butler Yeats that we are slouching toward Bethlehem.

Of course, as Washington Post columnist George Will says, the inevitable isn’t necessarily inevitable. However, at the moment, it looks as if it is.

The despair is spread pretty evenly among Democrat, many of whom consider President Biden too old, and Vice President Kamala Harris not up to the job she has, let alone the presidency.

At 80, Biden is showing reduced vigor and limited mobility, and he favors scripted speeches. This from a politician who was famous for nonstop talking.

Over the years, like other reporters, I have often thought, “Joe, you have made your point, now stop.” These days, you wait in vain for him to go off script. His speeches, which he reads from a Teleprompter, sound as though they were prepared by a committee — lifeless repetition.

He never holds a press conference, a sign of dwindling confidence.

The bigger fear in the Democrats isn’t that Biden is too old but that Harris, at some point, may become president. She has proven herself to be woefully inept and incoherent.

In every assignment Biden has handed her on which she could have shown her worth, she has failed or simply not done. Remember, she was Biden’s point person on the border crisis? She hasn’t been heard from as such.

This past spring, she went to Ghana, Tanzania and Zambia to counter the Chinese and chose to make it an occasion to apologize for slavery. I was born and raised in Africa, in what is now called Zimbabwe, and have traveled extensively on the continent, and slavery isn’t a burning issue. The high point of this visit was Zambia, where Harris’s paternal grandfather came from and where she was welcomed.

China has three great appeals to African countries: It asks no questions, doesn’t lecture on human rights, and pays off the ruling elites, trading these indulgences for minerals.

While Biden and Harris may seem a dangerous pair, Donald Trump, twice indicted (so far), twice impeached, now reduced to feeling sorry for himself on a colossal scale, is terrifying. He has promised an administration of vengeance.

Whereas I can’t find any Democrats who are enthusiastic about the Biden-Harris ticket, I certainly can find far-right Republicans who love Trump. Mostly, they are the working-class White voters, who were once the mainstay of the Democratic Party and now believe that the America they know and want to preserve can only be saved by the reprehensible Trump, with his relentless abuse of all who cross him and endless lachrymose pity for himself.

Trump’s defense of himself is risible, but the faithful Trumpsters believe in him — as much as ever.

They aren’t statistics to me. Recently, my wife and I were eating at a Chinese restaurant in Rhode Island when a couple with a small child took the booth behind us. You might call them the salt of the earth: working people doing their best to raise a family. The husband was complaining loudly about the high cost of living. Then, after seeing Trump on an overhead TV, he said to his wife, “The only honest man is Trump.”

That young father wasn’t alone.

At a neighborhood pub that, in the British sense, is our “local,” the owner and patrons know that both my wife and I are journalists, and because Rhode Island PBS airs our program, White House Chronicle, we are treated with deference. But that doesn’t prevent good, hard-working, fellow patrons, mostly of Italian, Irish and Portuguese stock, from lambasting the media within earshot of us. “It’s all lies.” “They hate Trump because he tells the truth.” They say things like that because they believe them. They are the Trump base.

When I hear that stuff, how do I react? Well, I roll my eyes, sigh, shrug my shoulders, and, if no one is looking, I turn my hands up to the heavens.

On Twitter: @llewellynking2

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS.

John S. Long: June walks on Gaspee Point

View of Gaspee Point from the north. Taken from across Passeonkquis Cove.

—Photo by Magicpiano

June 3, 2023

I’m walking on Gaspee Point, in Warwick, R.I., again. The wind is out of the northeast at a steady 16 mph, and it feels 10 degrees cooler. I see an Osprey atop its nest, but to my distress the nest seems otherwise unoccupied following days of unrelenting rain. Tomorrow is a full moon (a Strawberry Moon), and the tide is quite low. Gray clouds and a slate-gray Narragansett Bay stretch out, southeast, toward Colt State Park, in Bristol. Wind is whooshing through the trees. Otherwise, there’s silence except for a weed whacker sounding off above me on Gaspee Point’s high banks.

Only a handful of walkers are on the beach and the breakwater today. Iterations of waves intrude on the silence. Rain recommences, and I recall (from several weeks ago) a great cacophonous raft of Brant Geese set to embark on their stunning 2,500-mile migration to Greenland’s north coast nesting areas.

There are many seaside thickets, and pink, red and white beach roses bloom far back from high tide. Wind-driven drizzle comes, but I’m sheltered by a grove of American Elderberry trees.

There’s new sand in perfect smoothness--a beach nearly without human tracks.

June 10, 2023

I can hear a pair of Ospreys (cheereek, cheereek) on their nesting platform. Briefly, I think I’m seeing the female Osprey’s head as it pops up from the nest. Immediately, I’m wondering if there are baby Ospreys in the nest, even though it has been an cold fledgling season.

Now it’s high tide, and the wind’s from the southeast. Earlier this afternoon we had a passing shower.

Six Cormorants are resting and drying their wings on a broken erratic boulder 200 feet offshore. In winter water freezes within the boulder’s numerous cracks and pries it open oh so slowly.

A swath of the eastern sky is a robin’s egg blue with puffy clouds drifting in from the southeast.

On a shoal, edging the shipping channel, three quarters of a mile from shore is what had been Bullock Point Lighthouse--but only its granite pier remains. In my mind’s eye images of a Victorian gabled structure (1872) continue to fascinate me.

Walking north up the beach I note that one of the Ospreys (probably the male), with its wings nearly six feet across, brings new nesting branches clutched in his talons in a wide loop toward the nesting platform. A successful new family of Ospreys?

John S. Long lives in Warwick.

Relishing ruins

At “The Bells,’’ in Newport

— Photo by GoLocalProv.com

The amphitheater, artificial ruins in Maria Enzersdorf, Austria, built in 1810/11

— Photo byu C.Stadler/Bwag

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

The state-owned, graffiti-rich carriage house and stables of a once stately Newport mansion, which was built in 1876 and called “The Bells’’ and torn down in the ‘60s, will finally be demolished. That’s after four young people who were playing there were injured when part of the roof collapsed. The structures probably should have been demolished years ago.

Newport has its fair share of residential monuments from the first Gilded Age (semi-officially roughly 1870-1900, though some extend it through The Twenties), but I’d guess that few if any, others are in such a mess as “The Bells.’’ The current Gilded Age, still going strong, began in the 1980s, when, under the Reagan administration, taxes were slashed for the very rich.

Places like “The Bells’’ lure young “explorers,” especially boys, intent on mischief or innocent fun. I well remember as a kid entering (i.e., trespassing) such decayed mansions along the Massachusetts Bay shoreline near our house. Most were, or had been, summer places. Perhaps some were abandoned, or just started to be neglected, when the owners ran out of money in The Depression. Most were gray-shingle houses that started to be put up after the Civil War. But some of the newer ones had Spanish Mission-style stucco walls, fountains and statuary, which were popular in The Roaring Twenties. Newly (if only briefly) rich people liked what they saw of these houses on Florida’s Gold Coast and in Los Angeles.

Kids would smoke in them (raising the danger of fire) or engage in such idiotic behavior as BB gun fights.

In the 18th Century and early 19th centuries in Europe, especially in England, there was a mania for building fake ruins; some draw tourists to this day. Maybe some falling-down Newport mansions can someday serve a similar purpose. Crumbling old houses covered with vines can look romantic, and are spawning grounds for entertaining ghost stories. Just kidding. The building inspectors probably wouldn’t allow it.

Llewellyn King: Smoke spreads amidst global warming but beware overzealous regulation

Smoke from Canadian forest fires in the Delaware River Valley. See New England’s “Dark Day’’.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

The smoke from wildfires in Canada that has been blown down to the United States, choking New York City and Philadelphia with their worst air quality in history and blanketing much of the East Coast and the Midwest, may be a harbinger for a long, hot, difficult summer across America.

It could easily be the summer when the environmental crisis, so easily dismissed as a preoccupation of “woke’’ Greens and the Biden administration, moves to center stage. It could be when America, in a sense, takes fright. When we realize that global warming is not a will-or-won’t-it-happen issue like Y2K at the turn of the century.

Instead, it is here and now, and it will almost immediately start dictating living and working patterns.

In an extraordinary move, Arizona has limited the growth in some subdivisions in Phoenix. The problem: not enough water. Not just now but going forward.

The floods and the refreshing of surface impoundments, such as Lake Mead and Lake Powell, the nation’s largest reservoirs, haven’t solved the crisis.

All along the flow of the Colorado River, aquifers remain seriously depleted. One good, rainy season, one good snowpack may recharge a dam, but it doesn’t replenish the aquifers that hydrologists say have been undergoing systematic depletion for years.

An aquifer isn’t just an underground river that runs normally after rainfall. It takes years to recharge these great groundwater systems. These have been paying the price of overuse for years; across Texas and all the way to the Imperial Valley, in California, unseen damage has been done.

It isn’t just water that looms as a crisis for much of the nation, there is also the sheer unpredictably of the weather.

I talk regularly with electric- and gas-utility company executives. When I ask them what keeps them awake at night, they used to respond, “Cybersecurity.” Recently, they have said, “The weather.”

This year, we are entering the tropical-storm season with unusually warm ocean temperatures in the Atlantic and the Pacific. The doleful conclusion is that these will signal severe and very damaging weather activity across the country.

The utilities have been hardening their systems, but electricity is uniquely affected by weather. The dangers for the electricity industry are multiple and all affect their customers. Too much heat and the air-conditioning load gets too high. Too much wind and power lines come down. Too much rain and substations flood, poles snap and there is crisis, from a neighborhood to a region.

In the electricity world, the words of John Donne, the 16th-Century English metaphysical poet, apply, “No man is an island entire of itself.”

There is another threat that the electricity-supply system will face this summer if the weather is chaotic: overzealous politics and regulation.

It is the electric utilities that are most identified in the public mind with climate change. The public discounts the myriad industrial processes as well as the cars, trucks, bulldozers, trains and ships that lead to the discharge of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. Instead, it is utilities that have a target pinned to them.

A bad summer will lead to bad regulatory and bad political decisions regarding utilities.

Foremost are likely to be new attacks on natural gas and its supply chain, from the well, through the pipes, into the compressed storage, and ultimately to combustion turbines.

At this time, natural gas – about 60-percent cleaner than coal — is vital to keeping the lights on and the nation running when the wind isn’t blowing, or the sun has set or is obscured.

The energy crisis that broke out in the fall of 1973, and lasted pretty well to the mid-1980s, was characterized by silly over-reactions. First among these was probably the Fuel Use Act of 1978, which got rid of pitot lights on gas stoves and even threatened the eternal flame at Arlington Cemetery.

It also accelerated the flight to coal because, extraordinarily, that was the time of the greatest opposition to nuclear power — from the environmental communities.

This summer may be a wakeup for climate change and how we husband our resources. But wild overreaction won’t quiet the weather.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS, and a long-time editor, writer and consultant in the international energy sector. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

#global warming #Llewellyn King #electric utilities

Mommy dearest?

“Urban Toile” (relief cut), by Boston artist Ellen Shattuck Pierce, in the group show “Oh, Mother,’’ at Hera Gallery, Wakefield, R.I., through June 17

— Image courtesy of Hera Gallery.

The show is a national juried exhibition that brings together 27 artists to analyze, the gallery says, "motherhood in all its complexity, as well as at the absence of desired motherhood.’’

The Bell Block in the old commercial section of Wakefield, built when there were numerous manufacturing and farm operations in that village of South Kingstown, which now has many summer and weekend residents because of the coastline.

Certain kinds of intensity

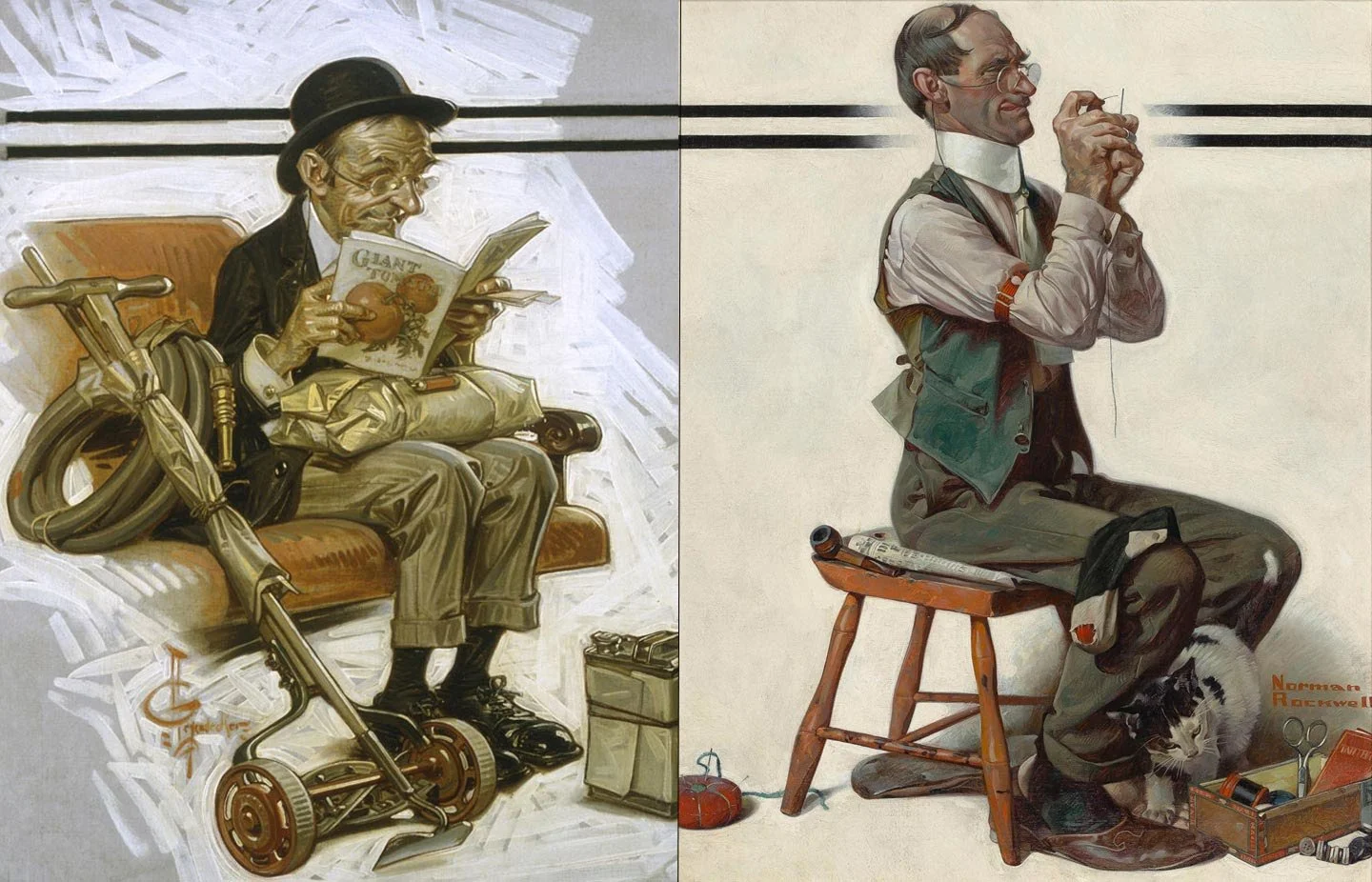

Left, “Spring Commuter’’ (oil on canvas), by J.C. Leyendecker (1870-1951), for the May 6, 1916 cover of The Saturday Evening Post. Right, “Threading the Needle” (oil on canvas), by Norman Rockwell, for the April 8, 1922 cover of the same magazine. Both at the National Museum of American Illustration, Newport, R.I.

The western facade of the mansion Vernon Court, at 492 Bellevue Ave., Newport R.I., home of the National Museum of American Illustration. It was built in 1900.

Llewellyn King: What made me an AI enthusiast.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

I have gone over. All the way. I have fallen in love with artificial intelligence. We need it, and I’m on board.

My conversion was sudden. It happened on one memorable day, Feb. 8, 2023. It was a sudden strike in a well-worn heart by Cupid’s arrow.

My love life with technology has been either unrequited or messy. I was always the one who blew the relationship, I admit that.

It started with computer typesetting. I was a committed hot-lead-type man. I didn’t want to see that painted lady, computer technology, destroying my divine relationship with hot type. But she did and when I tried to make amends, she was, er, cold, froze me out.

Likewise, as an old-time newspaperman, I was very proficient and happy with Telex. Computer technology separated us.

The worst of all was my first encounter with the internet.

I was pursuing the story of nuclear fusion at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, in California. A lab technician tried to interest me in the new device he was using to send messages: the Internet. I blew it off. “That is just Telex on steroids,” I said.

Ms. Internet doesn’t care to be scorned and she nearly cost me my manhood — well, my publishing company — when she took her terrible revenge. She killed print papers as well as hot type. She was a vengeful siren that way.

My conversion to AI began innocently enough. I was listening to a reporter on National Public Radio explaining how Microsoft’s new AI search engine would not only change the world of online searching but would also give Google a serious run for its money — billions of dollars, I might say parenthetically.

The writing's on the wall for Google unless it can get its AI to market fast. I was intrigued.

The illustration used by NPR reporter Bobby Allyn was that of buying a couch and carrying it home in your car. The new search engine, Allyn explained, will tell you if the couch you want to buy will fit in your car. It will know the dimensions of the car and, maybe, of the couch too. Wow!

Then I went on to watch a wild, unruly hearing before the U.S. House Oversight Committee. A long-suffering panel of former Twitter executives faced some pointed abuse from the Republican members. Some of those members never got to pose a question: Their time was entirely taken up castigating the witnesses over alleged collusion with the Biden administration and over Hunter Biden’s laptop — the holy grail for conspiracy theorists. It was a performance worthy of a Soviet show trial.

The worst aspects of the new House were on display. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D.-N.Y.) was visibly flustered because she wasn’t in her seat when her time to question the witnesses arrived. She rushed back to it and was so excitable that she was nearly incoherent.

Then there was Marjorie Taylor Greene (R.-Ga.), who was adamant that Twitter was advancing a political agenda by accepting the science that vaccines helped control the COVID-19 outbreak. She asserted that Twitter had a political objective when it denied her free-speech rights by suspending her account, after frequent warnings about her dangerous public health positions opposing vaccinations.

The lady's not for turning. Not by facts, anyway. That was clear. Any Southern charm she may possess was shelved in favor of invective. She told the former Twitter executives that she was glad they had been fired.

The clincher in my conversion to AI had nothing to do with the brutal thrashing of the experts, but with the explanation by Yoel Roth, former head of Trust and Safety at Twitter, who with forbearance explained that there were then and are now hundreds of Russian false accounts on Twitter aimed at influencing our elections and reaching deeply into our politics. Likewise, Iranian and Chinese accounts.

That is when it occurred to me: AI is the answer. Not the answer to the mannerless ways of the House hearing, but to the whole vulnerability of social media.

We have to fight cyber excess with cyber: Only AI can deal with the volumes of malicious domestic and foreign material on the net. Too bad it won’t resolve the free-speech issues, or the one that emerged at the House hearing: the right to lie without restraint.

This AI doubter is now an enthusiast. Bring it on.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington. D.C.

Llewellyn King: My brief for America’s embattled police

Los Angeles Police Department officers arresting suspects during a traffic stop. Such stops can be life-threatening for the police.

— Photo by Jim Winstead

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

Police excess has gained huge attention after the death of George Floyd, in Minneapolis in 2020, and the alleged beating death of Tyre Nichols, in Memphis, last month. But police excess isn’t new.

A friend of mine, who had been drinking and could be quite truculent when drunk, was severely beaten in the police cells in Leesburg, VA., a couple of decades ago. I have never seen a man so badly hurt in a beating -- and I have done my share of police reporting.

That he provoked the police, I have no doubt. But no one should be beaten by the police anywhere, ever, for any amount of provocation. I might mention that my friend -- and the officers who might have killed him -- were white.

I used to cover the Thames Police Court, in the East End of London. That was before immigration had changed the makeup of the East End. It was then, as it had been for a long time, solidly white working class.

Every so often, a defendant would appear in the dock showing signs that he had been in a fight. One man had an arm in a sling, another had a black eye, a third had bruises on his face. One thing was common: If they looked beaten-up, they would be charged with “resisting arrest,” along with such other charges as drunkenness and petty larceny.

In the press benches, we shrugged and would just say something like, “They worked that bloke over.” We never thought to raise the issue of police brutality. It was just the way things were.

At least nowadays, when social norms don’t allow for police hitting suspects, there is a slight chance of redress. Although I would wager that nearly all police violence goes unreported, and the “blue wall” closes tightly around it.

People in uniform, men and women, hold dominion over a prisoner. If there is ethnic bias or verbal provocation, bad things can and do happen.

Yet I hold a brief for the police. Policing is dangerous and heartbreaking work, especially in the United States where guns are everywhere, Also it is shift work, itself a stressing factor.

Wearing the blue isn’t easy, and abuse and danger go with the job. Sean Bell, a former British policeman, now a professor at the Open University, described the police workload in the United Kingdom this way, “Those in the policing environment can become a human vacuum for the grief, sorrow, distress and misfortune for the victims of crime, road crashes and the plethora of other incidents dealt with time after time.”

Many of the incidents of American police being shot and police exceeding their authority have as their genesis at a traffic stop, as with Tyre Nichols. These are a cause of fear for both the police and criminals. It is where the rubber meets the road of law enforcement.

We motorists form our opinions of the police largely through traffic stops, which we rail against. But to the police, they are a life-threatening hazard as they approach a car that may have a crazed or dangerous criminal driver with a gun. They face danger and tragedy in plain sight.

The only thing that police officers are more wary of than traffic stops are domestic-violence calls. They are the worst, officers in Washington have told me.

Yet the traffic stop is an essential police tool, partly for controlling traffic but importantly for arresting criminals, fugitives and drug transporters. It is how the police work within the constitutional prohibition on illegal search and seizure.

People who have control of other people — drill sergeants, wardens and the police — are in a position to abuse, and some do. A uniform and authority can bring out the inner beast. Remember what went on in Abu Ghraib prison, in Iraq?

Following the two terrible incidents of police excess, Floyd and Nichols, all the solutions seem inadequate. But when out on the streets or in our homes, most of us are vitally aware that we feel secure because a call to 911 will bring the law — the men and women in blue who guarantee our safety and well being.

What to do about police violence? Vigilance is the first line of defense, but appreciating the police as well as holding them to account helps. Not many police officers feel appreciated, and that isn’t good for them or for society.

“The policeman’s lot is not a happy one!” So wrote British dramatist W.S. Gilbert in The Pirates of Penzance, an 1879 comic opera, one of his collaborations with composer Arthur Sullivan.

And Gilbert and Sullivan had never dreamt of a traffic stop.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com and he based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

Boston has the oldest municipal police department in America.

Liability Lane

A noncollapsed part of Newport’s Cliff Walk.

— Photo by Giorgio Galeotti

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Will they soon have to patch and fill along and on Newport’s famous Cliff Walk every few months, what with rising seas and more intense storms? The latest drama came in a Dec. 23 tempest in which part of the walk’s embankment collapsed. A section of the walk itself collapsed last March in a storm.

Maybe they should change the name of this tourist attraction to Liability Lane.

But the big thing to watch in The City by the Sea is the redevelopment and, we hope, beautification, of the ugly North End.

Speaking of the tourist mecca of Newport, the country, including New England, will likely go into a recession this year, and unlike in the pandemic recession, the Feds can’t be expected to bail out the states. So the states better pump up their rainy-day funds. Rhode Island, for its part, should intensify its promotion of warm-weather tourism, especially in such nearby areas as Greater New York City, to get more sales tax revenue to help offset the decline in other tax revenue.

The joy and pain of shrinkage

Big enough

— Photo by Cavajunky

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

Many people at the end of the year reflect on whether they should make a major life change. This might include simplifying by downsizing where they live.

So I recommend Dr. Edward Iannuccilli’s latest book of essays, Essays on the Art and Pain of Downsizing. (He’s a friend, but no, I get no kickbacks for this plug.)

Of course, many older people, such as Dr. Iannuccilli, who lives in beautiful Bristol, R.I., downsize in part because of their stage of life. But there are good reasons for others to do so. You save on fuel, electricity, taxes and insurance and you’re disciplined to get rid of stuff, which can feel liberating. (Do some people have so much stuff that it acts as insulation, saving fuel in the winter?)

In 1980, the median size of a new house in the U.S. was 1,595 square feet. That ballooned to 2,386 square feet by 2018, with fewer people living in these houses. Obviously, the bigger the house, the bigger the purchase price and maintenance costs; the latter tend to be alarmingly unpredictable.

Town hall and Civil War memorial in Bristol, R.I.

Llewellyn King: 2022’s biggest crises will be 2023’s, too

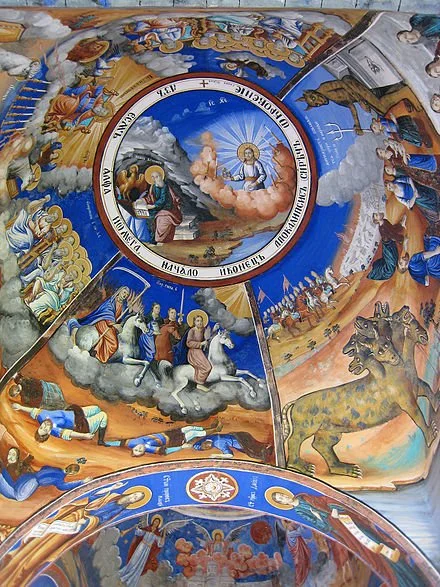

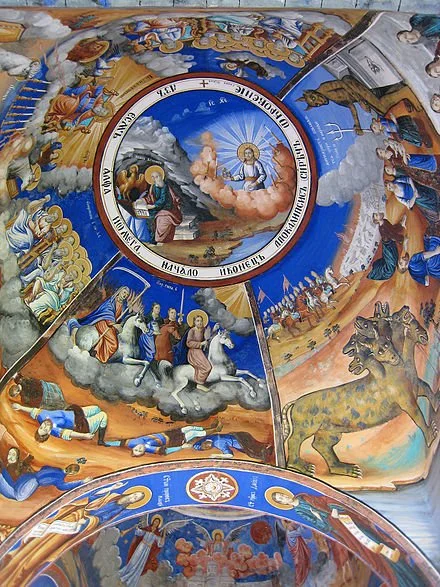

The Apocalypse, depicted in Orthodox Christian traditional fresco scenes in Osogovo Monastery, North Macedonia.

WEST WARWICK, R.I.

There are no new years, just new dates.

As the old year flees, I always have the feeling that it is doing so too fast; that I haven’t finished with it, even though the same troubles are in store on the first day of the new year.

Many things are hanging over the world this transition. None is subject to quick fixes.

Here are the three leading, intractable mega-issues:

First, the war in Ukraine. There is no resolution in sight as Ukrainians survive as best they can in the rubble of their country, subject to endless pounding by Russian President Vladimir Putin. It is as ugly and flagrant an aggression as Europe has seen since days of Hitler and Stalin.

Eventually, there will be a political solution or a Russian victory. Ukraine can’t go on for very long, despite its awesome gallantry, without the full engagement of NATO as a combatant. It isn’t possible that it can wear down Russia with the latter’s huge human advantage and Putin’s dodgy friends in Iran and China.

One scenario is that after winter has taken its toll on Ukraine, and the invading forces, a ceasefire-in-place is declared, costing Ukraine territory already held by Russia. This will be hard for Kyiv to accept -- huge losses and nothing won.

Kyiv’s position is that the only acceptable borders are those that were in place before the Russian invasion of Crimea in 2014. That almost certainly would be too high a price for Russia.

Henry Kissinger, writing in the British magazine “The Spectator,” has proposed a ceasefire along the borders that existed before the invasion of last February. Not ideal but perhaps acceptable in Moscow, especially if Putin falls. Otherwise, the war drags on, as does the suffering, and allies begin to distance themselves from Ukraine.

A second huge, continuing crisis is immigration. In the United States, we tend to think that this is unique to us. It isn’t. It is global.

Every country of relative peace and stability is facing surging, uncontrolled immigration. Britain pulled out of the European Union partly because of immigration. Nothing has helped.

This year 504,000 immigrants are reported to have made it to Britain. People crossing the English Channel in small boats, with periodic drownings, has worsened the problem.

All of Europe is awash with people on the move. This year tens of thousands have crossed the Mediterranean from North Africa and landed in Malta, Spain, Greece and Italy. It is changing the politics of Europe: Witness the new right-wing government in Italy.

Other migrant masses are fleeing eastern Europe for western Europe. Ukraine has a migrant population in the millions seeking peace and survival in Poland and other nearby countries.

The Middle East is inundated with refugees from Syria and Yemen. These millions follow a pattern of desperate people wanting shelter and services, but eventually destabilizing their host lands.

Much of Africa is on the move. South Africa has millions of migrants, many from Zimbabwe, where drought has worsened chaotic government, and economic activity has come to a halt because of electricity shortages.

Venezuelans are flooding into neighboring Latin American countries, and many are journeying on to the southern border of the United States.

The enormous movement of people worldwide in this decade will have long-lasting effects on politics and cultures. Conquest by immigration is a fear in many places.

My final mega-issue is energy. Just when we thought the energy crisis that shaped the 1970s and 1980s was firmly behind us, it is back -- and is as meddlesome as ever.

Much of what will happen in Ukraine depends on energy. Will NATO hold together or be seduced by Russian gas? Will Ukrainians survive the frigid winter without gas and often without electricity? Will the United States become a dependable global supplier of oil and gas, or will domestic climate concerns curb oil and gas exports? Will small modular reactors begin to meet their promise? Ditto new storage technologies for electricity and green hydrogen?

Energy will still be a driver of inflation, a driver of geopolitical realignments, and a driver of instability in 2023.

Add to worsening weather and the need to curb carbon emissions, and energy is as volatile, political, and controversial as it has ever been. And that may have started when English King Edward I banned the burning of coal in 1304 to curb air pollution in the cities.

Happy New Year, anyway.

Llewellyn King is executive producer and host of White House Chronicle, on PBS. His email is llewellynking1@gmail.com, and he’s based in Rhode Island and Washington, D.C.

‘We are still here’

The cairn in question.

Adapted from Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

I wrote too whimsically in an Oct. 23 column that I had come across this cairn while walking on the lawn at the Roger Williams National Memorial, in downtown Providence, and asked what it is. Here’s the answer from the National Park Service, via my friend Ken Williamson, who lives in Hawaii.

“This cairn, or stone pile, depicts pieces of Narragansett {Tribal Nation}

history from pre-contact {with Europeans} through today. Built by Narragansett artists associated with the Tomaquag Museum {in Exeter, R.I.} it expresses the fact that WE ARE STILL HERE. The cairn is at the center with 4 raised stones around it representing the Four Directions. It is a meditative circle, representing Narragansett lives, history, and future which brings us full circle. Sit down and reflect on your own past, present and future and its intersection with the Narragansett people.

“The Narragansett Tribal Nation has lived on these lands since time immemorial. Their ancestors respected all living things and gave thanks to the Creator for the gifts bestowed on them, as do Narragansett people of today. Lynsea Montanari & Robin Spears III, both Narragansett, served as summer arts interns at the memorial for this project. They incorporated their own cultural knowledge with teachings by tribal elders regarding first contact with European settlers, genocide, displacement, assimilative practices, enslavement, continuation of language, ceremony, and other cultural practices. The artists chose to create a cairn as it is a part of the history of all indigenous peoples. There are many historic cairns in the Narragansett landscape.’’

xxx

My strongest memory of Native American cairns comes from driving with my wife in the forests along the northern side of gorgeous Georgian Bay in Ontario. You can’t go far there without seeing a cairn or other stone sculpture on a slope above the road.

Tomaquag Museum, in the Arcadia section of Exeter, R.I.

—Photo by John Phelan