Chris Powell: ‘Affirmative action’ didn’t do much for Connecticut

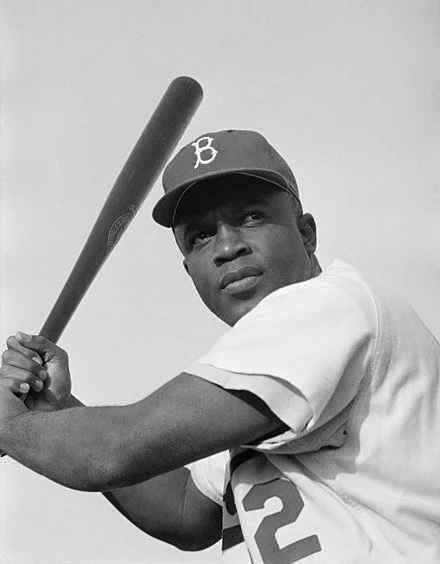

The triumph of talent: Jackie Robinson

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Despite the hysteria about the U.S. Supreme Court's decision prohibiting racial preferences in college admissions -- a policy long euphemized as "affirmative action" -- as a practical matter the country no longer needs the practice if it ever did. For government agencies and larger businesses long have been striving to hire and promote members of minority groups and women, either from the belief that such integration is a moral necessity or from a desire to be considered politically correct.

As public education eliminated its standards and declined steadily in recent decades, even smaller businesses whose managers were not especially enlightened began to discover that their prejudices could be expensive -- that they were often fortunate to find a qualified applicant of any background. Thus they realized what Brooklyn Dodgers manager Leo Durocher impressed on his reflexively racist players when they threatened to revolt if a Black man, Jackie Robinson, was to join the team, in 1947:

“I don't care if the guy is yellow or black or has stripes like a #@%&# zebra. I'm the manager of this team and I say he plays. What's more, I say he can make us all a lot of money. And if any of you #@%&# don't want it, I'll see that you're traded.”

The American creed was never better expressed, nor better vindicated. That is, merit will win in the end. Money doesn't care who spends it. Show that you can do the job if given a chance.

Members of minority groups applying for white-collar jobs began figuring this out 40 years ago when they inserted into their resumes markers of their minority status -- sometimes subtly, sometimes not. Far from handicapping their applications, minority status was conveying advantage. It still does -- if the applicant is reasonably competent.

The country's integration problem is not so much on the employers’ end anymore but on the qualifications end -- and it may be worse than it was prior to enactment of civil rights legislation.

This is easily seen in Connecticut, where Gov. Ned Lamont often acknowledges that the state's manufacturers are unable to fill about 100,000 well-paying jobs with excellent benefits. Meanwhile every year the state's high schools, especially those in the cities, graduate thousands of students, nearly all of them members of minority groups, who have never mastered basic subjects and so face lives of menial work, inadequate insurance, extra physical and mental health risks, housing insecurity, and propensity to crime.

These young people haven't needed help getting into college. They have needed help getting into life but have gotten it neither at home nor in lower education.

Indeed, Connecticut long has been notorious for its racial-performance gap in lower education. State government lately has decided that the solution is a little more tutoring for failing students -- many of whom often are not showing up at school in the first place, being chronically absent, perhaps in the confidence they well may share with whatever parents they have that they will be promoted and given diplomas no matter what -- confidence that, indifferent as Connecticut is to results in lower education, the state might as well award high school diplomas with birth certificates.

In any case a high-school diploma no longer automatically construes any sort of education and does not impress admissions officers at serious colleges nor personnel officers at advanced manufacturing companies that need skilled employees. A high school diploma is often an empty credential, as many college diplomas are.

"Affirmative action" never did much for Connecticut or the country. It didn't educate many young people. Mainly it advanced the less qualified and penalized those who took their studies seriously, especially students of Asian descent. It provided camouflage for the underlying problem, the welfare-induced collapse of the Black family famously noted in a research paper almost 60 years ago by the sociologist and future politician Daniel Patrick Moynihan, among the last of the true liberals.

Action in that respect is needed more urgently than ever, but in Connecticut it can't even be discussed.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years. (CPowell@cox.net)

Brigid Harrington: As high court decision looms, colleges search for alternatives to affirmative action

At Harvard’s campus, in Cambridge, Mass., the university’s seal.

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

The U.S. Supreme Court may ban race-based affirmative action for college admissions this year. But that does not mean that schools will abandon their diversity goals.

As administrators wait for the high court to issue its final decision in two key affirmative-action cases, they are figuring out how they can continue to create the heterogenous campuses they want.

It is not an easy task. In an effort to increase racial diversity on campus, many colleges already have experimented with changing early action and legacy rules to no avail. “There is no replacement for being able to consider race,” Olufemi Ogundele, the University of California at Berkeley’s dean of admissions, recently told The Washington Post. “It just does not exist.”

Still, schools are searching for viable alternatives. The justices signaled during oral arguments last fall that they were ready to overturn their 19-year-old ruling that allowed race to be a factor in admissions decisions. Even back in 2003, the court maintained that race was not the ideal way to achieve diversity, saying racial preferences would no longer be necessary within 25 years.

In the two cases currently before the court, Students for Fair Admissions sued Harvard University as well as the University of North Carolina (UNC), arguing that it was unconstitutional to use race as part of the holistic admissions process. The court is expected to issue its ruling in June.

Judicial scholars expect that the court will make no distinction between public and private universities, banning affirmative action for nearly every school. Groups that filed amicus briefs in the current cases argued for two exceptions: for certain faith-basedschools, which say their mission is to help the historically disadvantaged, and for military academies, which contend that diversity in the officer corps is critical for military cohesion. It remains to be seen how, or if, the court will consider such exceptions.

The vast majority of colleges include diversity as part of their mission statements. But they will now need to engage in some deep soul-searching to decide what diversity really means to them. Do they want only students of different races on campus or do they really seek diversity of student viewpoints and life experiences?

To be sure, race – especially in America – influences a person’s life experience, and most colleges would agree that having students interact with classmates from other races in itself is valuable. But there are many other types of diversity, too, and schools may want to balance them all, including cultural, religious, geographic and socio-economic diversity.

Colleges that do not engage in race-based affirmative actions have tried a variety of approaches to achieve diversity based on socioeconomic and other factors. Texas launched an innovative model more than 20 years ago, later adopted by Florida and California schools, that guarantees students admission to its flagship public universities if they graduated in the top 10 percent of their high school classes. This “top 10 percent plan” quickly became controversial and has had mixed results. It boosted Hispanic enrollment at leading public universities, but not Black enrollment, according to an analysis by The Texas Tribune. The law had minimal effects on application rates from low-income high schools, other analyses found.

Another potential approach: ending early admission. These programs are used mostly by affluent students with access to savvy college counseling, who know it’s far easier to get into top-rated schools by applying early. But ending the practice may not make much difference unless a lot of schools agreed to simultaneously make such a change. Harvard University ended early admissions in 2007 for five years, urging other Ivy League schools to join them. But when no other colleges halted their programs, Harvard’s ability to attract historically disadvantaged students plummeted. Top minority students simply chose other Ivy League colleges. After five years, Harvard restarted its early-action program.

In their search for alternatives to race-based affirmative action, some colleges may consider eliminating legacy preference programs. Since the vast majority of legacies are Caucasian, some education experts view this practice as unfair and arcane. Top British universities, such as Oxford and Cambridge, ended legacy admissions long ago in the name of equity, but American university administrators have argued that the number of legacies is so small that it wouldn’t affect diversity much.

Colleges that have ended legacy admissions report vastly different experiences. The University of California schools did not improve their diversity by banning legacy admissions. But Johns Hopkins University, which stopped legacy preferences in 2014, has seen a substantial increase in minority enrollment in recent years. The number of undergraduate minorities jumped by more than 10 percentage points between 2009 and 2020, and now more than one-fourth of the university’s undergraduates are minorities.

There’s one key difference between Hopkins and the University of California schools: affirmative action. Unlike the University of California, Hopkins still considers race as a factor in admissions. If the Supreme Court rules that all colleges – including Hopkins – must be race-blind, it’s not clear whether banning legacy admissions would make much difference.

Some colleges are thinking about focusing on socio-economic diversity rather than race, which could wind up increasing the number of historically-disadvantaged minorities since many such students are low-income. But that could prove tricky, too. Outside of the rarefied world of Harvard and UNC, there are limits to how many students from low-income backgrounds some colleges can admit because of financial constraints. Many simply do not have enough scholarship money to offer to these applicants.

In a race-blind admissions world, colleges may need to resort to asking its applicants for help. If they require a new essay, asking students how they could contribute to diversity on campus, they may discover all kinds of new ways to create the educational melting pot they really want. It may be schools’ best hope.

Brigid Harrington is a lawyer at Bowditch & Dewey LLP a Massachusetts firm. Her practice focuses on issues facing institutions of higher education. Email: bharrington@bowditch.com.

Chelsie Vokes: What will colleges do if Supreme Court bans affirmative action involving race?

At elite Williams College, in Williamstown, Mass.

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

When President Biden nominated Ketanji Brown Jackson for the U.S. Supreme Court, it seemed like a major civil rights victory.

But that victory could feel like a bitter irony this fall, when the high court hears two cases that will likely obliterate affirmative action. If Jackson gets approved by the Senate, she will probably be making two divergent types of history in her first months on the court: being its first black female and hearing cases that could likely overturn 40 years of legal precedents involving race-conscious admissions.

The cases, one against Harvard and the other against the University of North Carolina, were both brought by Students for Fair Admissions (“SFFA”), an organization founded by conservative entrepreneur and long-time affirmative-action foe Ed Blum. If the Supreme Court rules in favor of the plaintiffs, as expected, colleges and universities would not only be barred from using race as a factor in admissions but also prohibited from knowing the race of applicants.

The decisions will likely force schools to completely revamp their admissions policies and rethink how to apply for education grants. Depending on the scope and content of the Supreme Court’s ruling, the decision could affect preferences for first-generation students and reverberate well beyond the realm of education, even jeopardizing grant programs for minority-owned businesses. These cases could also lead to further scrutiny of common practices such as legacy admissions.

In the University of North Carolina case, SFFA argues that whites and Asian American applicants were discriminated against because the university used race as a criterion for admissions. Previous Supreme Court cases had ruled that colleges could use race as one of several criteria for admissions, while prohibiting the use of racial quotas. But now, SFFA says those precedents are wrong and that using race as a criterion is illegal.

Harvard has a holistic process to determine admissions, that is, considering each candidate’s entire high school career and not looking at race as an explicit factor. However, SFFA argued that the subjective and vague nature of these holistic policies leaves room for implicit bias and consequently holds Asian American applicants to a far higher standard than white applicants. In support of its argument, the SFFA questioned why Harvard admits the same percentage of Black, Hispanic, white and Asian American students each year, even though application rates for each racial group differ significantly over time. SFFA says that Harvard must design a new race-blind admissions system.

The court hasn’t issued any opinions on affirmative action since June 2016, which was before Donald Trump was elected president and eventually secured three staunchly conservative appointments to the bench. Unless something unexpected occurs in the next year, it seems likely that the court will ban affirmative action.

The legal change could have huge implications for colleges and universities. If affirmative action is struck down, many colleges will need to overhaul their admissions practices. More than 100 public colleges currently use race as an admissions factor and 59 of the top 100 private colleges consider race as well, according to data from the College Board reported by Ballotpedia. Numerous other colleges that don’t consider race may need to determine whether their admissions policies disproportionally affect one race over others—a big undertaking that could require protracted and complicated analyses.

Colleges believe that diversity is critical to the spread of ideas. But without any race-conscious admissions policies, it’s likely that there will be substantially fewer minorities on many campuses. Past affirmative action bans decreased Black student enrollment by as much as 25% and Hispanic student enrollment by nearly 20%, according to a 2012 study cited by the Civil Rights Project. These bans discourage minority applicants and don’t even result in better academically credentialed student bodies. The Civil Rights Project also reported that SAT math scores dropped by 25 points after such bans.

If the court bans affirmative action, though, colleges and universities can find other methods to create the diverse campuses they desire. Like private employers, who generally can’t consider race in hiring, they could work to expand their applicant pool and encourage minorities to apply. They might also develop increased financial aid and other support programs to boost access to education.

States looking for a race-neutral alternative may follow the lead of Texas, which guarantees public university admission to all students who graduated in the top 10% of their high school classes. However, it is still unclear whether this approach really increases diversity.

Colleges and universities will be able to find ways to preserve—and boost—diversity on their campuses. But they should not wait until the court issues what will likely be a landmark affirmative action decision in the spring of 2023. Colleges and universities will need to make sweeping changes to admissions policies. They need to start preparing now.

Chelsie Vokes is a labor, employment and higher education lawyer with Bowditch & Dewey LLP, in Boston.

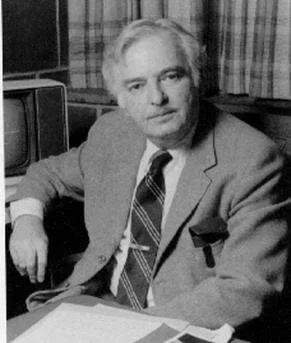

Stephen J. Nelson: Of visionary John Kemeny and decades of court battles over affirmative action at colleges

John G. Kemeny (1926-1992), Hungarian-born mathematician, computer scientist and president of Dartmouth College in 1970-1981

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

BOSTON

The U.S. Supreme Court is taking up affirmative action at colleges and universities for the sixth time in 50 years. In that litany, an early case was the University of California vs. Bakke. Bakke complained about being denied admission to the university’s medical school because seats were guaranteed for minority applicants, thus barring the door to him and other white applicants.

When the Bakke case was on the court’s docket, John Kemeny was president of Dartmouth College, in Hanover, N.H. The Dartmouth board of trustees wanted a public statement by the college on Bakke. Given their strong confidence in Kemeny, they gave him sole authority to craft Dartmouth’s stand on affirmative action. Kemeny’s voice from his bully pulpit into the public square about the Bakke case echoes today.

Kemeny’s argument displays ahead-of-the-curve insights. His major concern, one still very much at stake in the outcome of the court’s deliberations today, was that colleges had to be able to maintain their fundamental purposes in the face of any court judgment. Should the court mandate a cookie-cutter approach for college admissions, the unintended consequence would be to reduce diversity among institutions of higher education something that Kemeny said simply would be “highly undesirable.”

Using Dartmouth’s example, Kemeny underscored that the board had affirmed the college’s purpose as “the education of men and women with a high potential for making a significant positive impact on society.”

The board did not define that purpose as “the education of students who have the ability to accumulate high grade-point averages at the College,” a statement that would be “ludicrous!”

Kemeny pushed back against the court going over the edge if it were to compel colleges and universities exclusively to use test scores and presumed objective measures to decide which students to admit. That legal edict would restrict colleges from recruiting and admitting musicians, athletes and any student uniquely qualified to contribute to a student body and a college. Quotas of any sort were in his judgment “abhorrent.” Beware what you wish for.

Years after Bakke, in the 2003 University of Michigan cases, Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O’Connor asserted that colleges had roughly 25 more years to solve their equity and equal-opportunity problems. After that time, reliance on affirmative-action policies would run out. O’Conner’s clock continues to tick.

Getting to where she urged has proved difficult. Progress on the diversity front in the Ivory Tower is glacial and complicated because competing interests must be addressed and give their blessing or at least not actively resist new programs and initiatives. More time than O’Conner predicted is clearly needed. Ideological players on all sides agree that substantive changes in fairness and equity is the arrival point, though there will always be huge differences about the roadmap.

Greater diversity at colleges and universities makes their campus communities more engaging, more demanding, more rewarding and their members more fully educated. Absent diversity, the highest values of what we want a college education to be will remain outside our grasp. That is true for our body politic inside and outside the gates as graduates take their places in the social of communities and the nation. This picture is the goal, but how to get there and how long it will take are the great unknowns.

The new challenge brought by Students for Fair Admissions alleges that Harvard University discriminates against Asian-American students and the University of North Carolina discriminates against white and Asian- American applicants by continuing the use of race as an upfront criteria in admissions rather than observing a race-blind approach that would place more credence and consideration on an applicant’s struggles with discrimination in their life experiences.

The Supreme Court, of course, relies on arguments. The presidents of our colleges and universities must as a group get in the arena, present their case and gather defenders in amicus briefs. The cards will fall as the court dictates. However, jousting over what the Justices will say has to be embraced. It must be made clear to the court’s justices that they must not do harm to hard-fought policies designed to make our colleges and universities equitable, fair and open to diverse populations. Confining latitude and judgments about the scope of admissions procedures and aspirations to add greater diversity to their student bodies would rob colleges and universities of the very autonomy and freedom in their affairs that makes us the envy of the world. The shape of the future of diversity at our colleges is at stake and college presidents must weigh in with all the authority they can muster.

The voices of college presidents have to be front and center in this debate and in the court’s verdict. John Kemeny’s wisdom is a mantle that today’s presidents and those of us concerned diversity and equal opportunity on our campus must take up.

Stephen J. Nelson is professor of educational leadership at Bridgewater State University and senior scholar with the Leadership Alliance at Brown University. He is the author of the recently released book, John G. Kemeny and Dartmouth College: The Man, the Times, and the College Presidency. He has written several NEJHE pieces on the college presidency.

John Maguire: More affirmative action, not less, needed in elite college admissions

From The New England Journal of Higher Education, a service of The New England Board of Higher Education (nebhe.org)

This essay is a sequel to “The Human Dimensions of Enrollment Management,” published in The New England Journal of Higher Education on June 30, 2020. In that article, my unusual focus (as a trained theoretical physicist) was on integrity, not science, as the single most important factor in enrollment- management success. Early in my supervision of enrollment management (from a faculty position in the physics department at Boston College), I encountered serious challenges to that fundamental principle of integrity:

• In my first year (1972) on the job as dean of admissions at BC, one day was disrupted by a loudmouth self-proclaimed wealthy Texan in an ostentatiously large cowboy hat. He barged into my office, opened a checkbook and guaranteed me, and/or anyone I designated, “any amount necessary” to secure his son’s admission to Boston College. I evicted him summarily from our office and denied his son the right to apply.

• An influential alum (“Triple Eagle”) and BC administrator’s daughter appealed her rejection on the margin from the highly selective BC School of Nursing. The director of admissions offered the young woman a “Summer Challenge” of passing three courses (with B-‘s or better). Tragically, she received two A-‘s and a C+ and was never enrolled in the School of Nursing. That candidate was my daughter.

• In the late ’70s , the chairman of the Boston College Board of Trustees insisted to the president that his daughter be provisionally admitted to BC, despite her questionable credentials. The president requested that I “make this one exception to avoid a major political risk.” I reluctantly agreed—and the chairman’s daughter flunked out after one semester. Both the chairman and the president agreed thereafter to make the Admissions Office the final arbiter in all cases, even at the risk of losing millions of contributed dollars for new buildings and endowment.

• For at least five years into my tenure as leader of BC Admissions, I tolerated (even countenanced) the admission of virtually all wealthy Phillips Andover Academy seniors, even those in the bottom tenth of their class—while rejecting all but a handful of applicants, many in the top tenth of their classes, in low-income places such as Chelsea, Mass.

In an attempt to advance the principle of “affirmative action,” we completely reversed our strategy, rejecting many wealthy Andover applicants in favor of needy Chelsea applicants, with great results: More top Andover students began applying and gritty Chelsea students succeeded well beyond what their SATs might have predicted. Careful science-based research at BC documented the weak relationship between our ideal redefinition of “quality” (courageous, never-give-up grit, achievement against odds, work ethic—not wealth, social status) and test scores.

I take obvious pride in these displays of integrity by our enrollment team, which have served Boston College—and later other Maguire Associates client institutions—very well over these past 40-plus years.

These examples stand in stark contrast to the much-publicized multiple scandals of “Varsity Blues,” in which status-seeking celebrities are too often willing to write hundreds of thousands of dollars in checks, risk prison and disgrace, and dishonor their most sacred duty to (in the words of Crosby, Stills, and Nash) “teach your children well” about integrity and honesty.

At the highest levels of American leadership, there are now documented examples of secret payments to stand-in SAT test-takers to gain undeserved university admissions and to assist with writing assignments to cover up laziness and corruption—and nonstop braggadocio about fraudulent academic achievements. And too often the names of wealthy criminals remain on buildings and academic departments!

More recently, to underscore the offenses of the entitled well-to-do people whom I confronted earlier in my career—and who continue to seek unfair advantage in Varsity Blues pursuits—expensive legal actions on behalf of disproportionately “entitled well-to-do’s” are accusing Harvard and now Yale of law-violating affirmative action in attempting to do what Boston College accomplished quietly with the Chelsea/Phillips Andover case study. (I sometimes wonder how BC might have fared if a court action had been taken on behalf of Andover rejects losing seats to applicants from Chelsea.)

The great irony in evaluating the honorable ethical defenses (specifically, of white and Asian-American admission percentages, already among the highest in New England) that both Harvard and Yale have put forth is that (in my opinion) a stronger case can be made that too little “affirmative action” is being sought among highly endowed ultra-wealthy Ivies and NESCAC (New England Small College Athletic Conference) institutions. (The Ivy League schools are Harvard, Yale, Dartmouth, Brown, Princeton, Cornell, Columbia and the University of Pennsylvania.)

The following graph (prepared by me using firsthand data) presented at our 2017 Maguire Associates Tokyo Keynote (“The History and Future of Enrollment Management”) to a national group of Japanese universities is most revealing:

Under 20 percent, and in some cases under 10 percent, of family incomes at elite colleges and universities, are below the national median. And even more telling, of the 80 percent to 90 percent above the national median income, many are triple and more above that median. These institutions, with well under 5 percent of the total national college and university enrollment, control over two thirds of all endowment funds! (Note: Billion Dollar Club refers to the Ivies; the Selective Liberal Arts Colleges are generally NESCAC schools.)

Let me reintroduce the single most relevant and controversial commentary I have produced on this singularly important subject. The 2008 editorial, published in the Chronicle of Higher Education, entitled “‘Have Not’ Colleges Need New Ways to Compete With Rich Ones” needs to be revisited in light of the Harvard/Yale challenges from those accusing them of “too much” affirmative action. We wrote over 10 years ago:

“What we now have is a kind of caste system in American higher education: Brahmin institutions (among which the Ivies are among those at the top) —by virtue of their implicit endowment-supported, non-need-based discount—are able to have their pick of the best candidates in every category of students, including minority students. Hidden from view, expanding year by year, that implicit discount is constantly widening the gap between the haves and have-nots.”

“Roughly 50 institutions now control more than half of college and university endowment money while educating fewer than 2 percent of the nation’s students—a 2 percent that is disproportionately drawn from wealthy families.”

“To put it bluntly, the massive endowments of elite universities confer on them an unassailable competitive advantage in the form of a hidden discount that forces the less well-endowed institutions to deploy merit aid in a scramble for a diminished pool of the best and most-diverse students.”

“The wealthiest institutions would argue, of course, that because they are blessed with the luxury of more aid dollars they are already doing their share. And, in fairness, some of them are reexamining their policies to try to attract more low-income students.”

“Let’s face it, serving the have-not students has become, by default, the disproportionate responsibility of the have-not private institutions and the public four-year and community colleges.”

“We need to be open to new ideas, however unworkable they may, at first glance, appear.”

My point in describing the work we conducted at a now-elite university (Boston College) and in the quoted commentary above is that a stronger case can be made that America’s most elite institutions could and should be doing more—not less—in supporting affirmative action. In the Chronicle article, we advocated “offering donors bigger tax breaks for gifts to private institutions with smaller endowments.” Perhaps the ultimate “pipe dream” (our words in 2008!) that we proposed in the Chronicle piece was our “call for universities with huge endowments to share the wealth by partnering with less well-endowed institutions to extend the benefits of a high-quality education to a broader array of students.”

While I served as a trustee at two separate low-endowment institutions, their outstanding leaders actually did approach (regrettably, unsuccessfully thus far) institutions with multibillion-dollar endowments in pursuit of innovative partnerships that could become win/wins.

I proudly congratulate my own alma mater, Boston College, for investing tens of millions of dollars in creating the Pine Manor Institute for Student Success to dramatically enhance BC’s already above-average diversity—while creating the most possible positive outcome for its financially challenged neighbor, Pine Manor College. More such partnership initiatives should be pursued by the most elite institutions. It may be past time to revisit those “pipe dream” partnerships.

A wonderful example: Brown University has gifted $10 million to the public school system in its home city of Providence. This is perhaps a challenge to, say, Harvard and Yale to invest (even more?) in boosting education in their home cities of Cambridge and New Haven. Let us all continue to brainstorm on other innovative strategies for increasing educational equality.

John Maguire is founder and chairman of Concord, Mass.-based Maguire Associates, a higher-education consulting firm.

Why Harvard's weird take on Asian-American applicants?

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

U.S. District Judge Allison Burroughs has ruled that Harvard’s admissions process doesn’t discriminate against Asian-American applicants, though, she wrote, the university could improve the process with more training and oversight.

But a mystery: Judge Burroughs noted that Asian-American applicants generally got lower ratings on such qualities as integrity, fortitude and empathy. How would Harvard admissions officers come up with such measurements? Makes no sense to me.

Anyway, Harvard and other very selective schools take into account ethnicity among many other factors in putting together a first-year class. The admissions process at elite institutions has to be complicated as the schools strive for diversity so that their schools are at least marginally representative of America. For the courts and other parts of government to try to micromanage the process, especially at private institutions, is inappropriate.

This issue is particularly resonant in New England, with so many highly selective schools, most famously four (Harvard, Yale, Brown and Dartmouth) of the eight Ivy League schools and MIT. Ed Blum, the lawsuit’s originator, was previously involved in challenging the University of Texas’s affirmative-action program. Blum is a right-wing zealot whose efforts would restore what has in effect been white privilege to the admissions process.

Affirmative action for the affluent!

Tower Room in the Baker Memorial Library at Dartmouth College.

From Robert Whitcomb’s “Digital Diary,’’ in GoLocal24.com

“Americans are the only people in the world known to me whose status anxiety prompts them to advertise their college and university affiliations on the rear window of their automobiles.’’

-- The late Paul Fussell

The federal government is suing Harvard as part of the Trump administration’s drive against affirmative action in college admissions (and elsewhere). Its angle is to assert that Asian-Americans, many of whom have very strong high-school records, should be admitted in higher percentages. What is left unspoken is that the Trump plan is also meant to help white applicants, who, at least in part because they tend to come from more privileged backgrounds than African-Americans and Hispanics, also tend to have better high-school records.

I think that the Feds should bug out of the college-admissions controversy. All elite colleges, including all eight Ivy League schools, use a wide variety of criteria to try to make sure that their undergraduate student bodies have at least a vague resemblance to the population of the nation that these schools have served very well. Indeed, the schools are jewels of American culture, having helped to produce much cultural, technological and financial wealth. Consider the scientific breakthroughs in the institutions’ labs.

Anyway, despite the schools’ efforts at affirmative action, students from affluent backgrounds (overwhelmingly white) dominate these schools because of the economic, educational and social advantages (including better public and private schools) they’ve grown up with. Students must be careful to pick the right parents! If the administration wins, the colleges will be even more skewed to the rich. Such skewing is what helped Jared Kushner get into Harvard despite a mediocre high-school record. Daddy wrote a check to America’s oldest college for $2.5 million. And Donald Trump’s transfer to the University of Pennsylvania from Fordham was lubricated by his father’s wealth.

As this Bloomberg story reported:

“A Harvard dean was thrilled. The undergraduate college had just admitted the offspring of some wealthy donors, and now the money was expected to pour into the university.

"’I am simply thrilled about all the folks you were able to admit,’ David Ellwood, then the dean of {Harvard’s} John F. Kennedy School of Government, wrote to {Harvard College} Dean William Fitzsimmons on June 11, 2014. ‘All big wins. [Name redacted] has already committed to building and building. [Name redacted] and [name redacted] committed major money for fellowships -- before the decisions (from you) and are all likely to be prominent in the future. Most importantly, I think these will be superb additions to the class."

There will always be affirmative action for the rich, even at Harvard, with a $39 billion endowment.

Oh, well: Not all the big donors’ gifts go to putting up grandiose buildings with their names plastered on them and endowed professors’ chairs, also with donors’ names plastered on them. Some goes to fellowships and scholarships.

To read more, please hit this link.

Trump move against colleges' affirmative action on race is good news for affluent white students

Dartmouth Hall at Dartmouth College, in Hanover, N.H. Dartmouth is one of the four Ivy League universities in New England. The others are Harvard, Yale and Brown.

From Robert Whitcomb's "Digital Diary,'' in GoLocal24.com

That the Trump administration has decided that the federal government will no longer encourage colleges and universities to use race in the admissions process, reversing Obama-era guidance meant to promote diversity, will have the least effect on the nation’s richest, most prestigious and thus hard-to-get-into colleges and universities, of which New England has a lot. They get so many applicants and have so much financial aid to give out that they can easily create very diverse classes. The schools want to show such diversity in part because it reinforces their position as national and even international institutions. They want their students’ faces to look like the, well, world.

Using race as one criterion among others also has socio-economic-diversity effects– e.g., African-American and Hispanic students tend to come from poorer families than white and many Asian families.

Meanwhile, the Feds are investigating Harvard for alleged racial bias after complaints from some Asian-Americans that the admissions process is skewed against them.

Harvard has argued that it “does not discriminate against applicants from any group, including Asian-Americans’’ and notes that this group currently makes up a hefty 22.2 percent of students. But some rejected applicants say that’s too low considering their high marks and other indicators of future success.

We should leave to the colleges what sort of mix they need and want. Barring provable racial bias, the Feds shouldn’t try to manage colleges’ decision-making.

Trump’s policy, which will appeal to his mostly white base, will mean that poorer schools (public and private) will be less likely to offer admission to minorities. They’ll become whiter even as the Ivy League and other highly selective colleges maintain their affirmative-action programs. Poorer, less prestigious schools could try to maintain racial diversity indirectly, especially by providing more financial aid on the basis of a family’s finances – again, African-Americans and Hispanics tend to be considerably poorer than whites – but in a time of fiscal austerity for many colleges and universities and a shrinking number of overall applications because of demographic change, don’t bet on it.

The Trump policy will tend to favor affluent whites and widen the class divide.

Affirmative-action angst

The earliest known image of Dartmouth College, Hanover, N.H., in the February 1793 issue of Massachusetts Magazine. The college, officially founded in 1769, was an outgrowth of a Connecticut school for educating Native Americans founded in 1755.

From Robert Whitcomb's "Digital Diary,'' in GoLocal24.com

In other education news, the Trump administration, playing to its white male base, wants to sue colleges to block affirmative-action programs aimed at increasing the number of people of color on campuses. The implication is that black and Hispanic students get far more help than do white kids. (Asian-American students are put in another category.)

I’m not crazy about formal affirmative-action programs but colleges have, and should have, many things to consider when putting together classes. For example, many of the most prestigious colleges, including the Ivy League, give a big preference to “legacies,’’ those students, most of whom are white, with alumni parents or other close relatives.

Indeed, rich (mostly white) kids get a big advantage in admissions. First, they (or, rather, their families) can pay full tuition, a not minor consideration for admissions officers. Second, being already affluent, they and their families are naturally more likely to donate to their colleges before and after graduation – especially the legacy students. Thus Jared Kushner, with mediocre high school marks, got into Harvard – after his father donated $2.5 million to that illustrious institution. It’s unknown if Donald Trump’s rapacious multimillionaire real-estate operator father, Fred, wrote a donation check to get young Donald Trump into the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School as a transfer student from Fordham.

Finally, a thought experiment forwhite people: Do you really think that life would have been easier for you as a black person?

Probablythe fairest way to do college affirmative action in our increasingly genealogically plutocratic society is to make more of an effort to enable low-and-middle-income to attend. That would particularly benefit people of color, as well as poor whites.