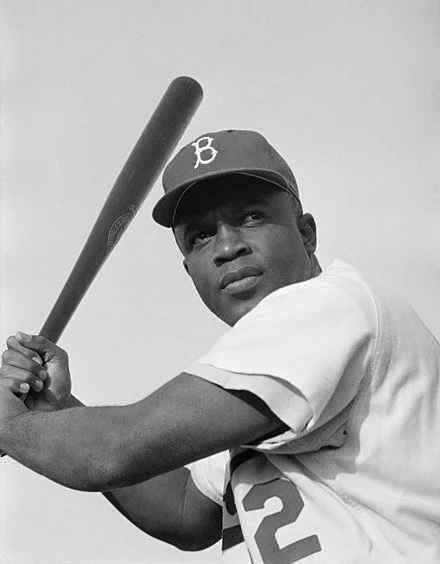

The triumph of talent: Jackie Robinson

MANCHESTER, Conn.

Despite the hysteria about the U.S. Supreme Court's decision prohibiting racial preferences in college admissions -- a policy long euphemized as "affirmative action" -- as a practical matter the country no longer needs the practice if it ever did. For government agencies and larger businesses long have been striving to hire and promote members of minority groups and women, either from the belief that such integration is a moral necessity or from a desire to be considered politically correct.

As public education eliminated its standards and declined steadily in recent decades, even smaller businesses whose managers were not especially enlightened began to discover that their prejudices could be expensive -- that they were often fortunate to find a qualified applicant of any background. Thus they realized what Brooklyn Dodgers manager Leo Durocher impressed on his reflexively racist players when they threatened to revolt if a Black man, Jackie Robinson, was to join the team, in 1947:

“I don't care if the guy is yellow or black or has stripes like a #@%&# zebra. I'm the manager of this team and I say he plays. What's more, I say he can make us all a lot of money. And if any of you #@%&# don't want it, I'll see that you're traded.”

The American creed was never better expressed, nor better vindicated. That is, merit will win in the end. Money doesn't care who spends it. Show that you can do the job if given a chance.

Members of minority groups applying for white-collar jobs began figuring this out 40 years ago when they inserted into their resumes markers of their minority status -- sometimes subtly, sometimes not. Far from handicapping their applications, minority status was conveying advantage. It still does -- if the applicant is reasonably competent.

The country's integration problem is not so much on the employers’ end anymore but on the qualifications end -- and it may be worse than it was prior to enactment of civil rights legislation.

This is easily seen in Connecticut, where Gov. Ned Lamont often acknowledges that the state's manufacturers are unable to fill about 100,000 well-paying jobs with excellent benefits. Meanwhile every year the state's high schools, especially those in the cities, graduate thousands of students, nearly all of them members of minority groups, who have never mastered basic subjects and so face lives of menial work, inadequate insurance, extra physical and mental health risks, housing insecurity, and propensity to crime.

These young people haven't needed help getting into college. They have needed help getting into life but have gotten it neither at home nor in lower education.

Indeed, Connecticut long has been notorious for its racial-performance gap in lower education. State government lately has decided that the solution is a little more tutoring for failing students -- many of whom often are not showing up at school in the first place, being chronically absent, perhaps in the confidence they well may share with whatever parents they have that they will be promoted and given diplomas no matter what -- confidence that, indifferent as Connecticut is to results in lower education, the state might as well award high school diplomas with birth certificates.

In any case a high-school diploma no longer automatically construes any sort of education and does not impress admissions officers at serious colleges nor personnel officers at advanced manufacturing companies that need skilled employees. A high school diploma is often an empty credential, as many college diplomas are.

"Affirmative action" never did much for Connecticut or the country. It didn't educate many young people. Mainly it advanced the less qualified and penalized those who took their studies seriously, especially students of Asian descent. It provided camouflage for the underlying problem, the welfare-induced collapse of the Black family famously noted in a research paper almost 60 years ago by the sociologist and future politician Daniel Patrick Moynihan, among the last of the true liberals.

Action in that respect is needed more urgently than ever, but in Connecticut it can't even be discussed.

Chris Powell has written about Connecticut government and politics for many years. (CPowell@cox.net)